E:\Pendrive\Mizo Studies Vol. I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No. 27009/1973 Postal Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) 2006-2008 VOL - XLV Aizawl, Friday 23.9.2016 Asvina 1, S.E. 1938, Issue No. 361 NOTIFICATION No.B.11035/60/2014-EDN, the 21st September, 2016. In partial modification of this Department’s Notification of even No. dated 3.3.2015, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to modify the Mizo Language Committee (MLC) under Mizoram Board of School Education as shown below :- 1. Chairman, MBSE Ex-Officio Chairman 2. Secretary, MBSE Ex-Officio Secretary 3. Director(Academic), MBSE Co-ordinator 4. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Mission Veng, Aizawl. Member 5. Pu KMS Dawngliana, Serkawn, Lunglei Member 6. Prof. Lalthangfala Sailo, Chaltlang, Dawrkawn. Member 7. Prof. Darchhawna, Kulikawn, Aizawl. Member 8. Pu C.Sangzuala, Ex-MLA, Chaltlang Dawrkawn. Member 9. Revd Chuauthuama, Ramhlun Venglai, Aizawl. Member 10. Dr.Lalzuia Colney, Kanan Veng, Aizawl. Member 11. Pu Chhuanliana, Bethlehem Vengthlang, Aizawl. Member 12. Pu C.Chhuanvawra, Tuikhuahtlang, Aizawl. Member 13. Pu R.Vanramchhuanga, Ramhlun Vengthar, Aizawl. Member 14. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Ramhlun South, Aizawl. Member 15. Pu B.Lalthangliana, Chhinga Veng, Aizawl. Member 16. Pu R.Rozika, Electric Veng, Lunglei. Member 17. Pu H.Ronghaka, Vaivakawn, Aizawl. Member 18. Pu Darchuailova Renthlei, Chaltlang Ruam Veng. Member 19. Pu Lalrinawma, Venghlui, Aizawl. Member 20. Pu R.Lallianzuala, Chanmari, Aizawl. Member 21. Prof. R.Thangvunga, Kanan Veng, Aizawl. Member 22. Pu R.Lalrawna, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Member 23. Pu Rozama Chawngthu, Mission Vengthlang, Aizawl. Member 24. Joint Director(S), Directorate of School Education. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

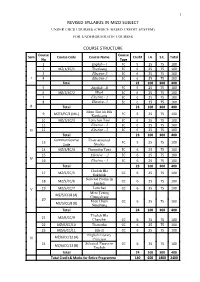

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1 Vol. V No. 2 April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES Vol. V No. 2 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) April - June, 2016 Editorial Board of Mizo Studies w.e.f April 2016.... Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Editor - Prof. R.Thangvunga Circulation Managers - Mr. Lalsangzuala - Mr. K. Lalnunhlima © Deptt. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal will not entertain any legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies April - June 2016 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Team Work - 5 English Section 1. Joseph C. Lalremruata Evolution of party Politics in Mizoram: A Study of the First Political Party - Mizo Union - 7 2. R. Thangvunga Magic and Witchcraft in Mizo Folklore - 17 3. Laltluangliana Khiangte Powerful Tones of Women in Mizo Folksongs - 23 Mizo Section 1. Darchuailova Renthlei Mizo |awng thl<k chhinchhiahna (Tone Markers)- 29 2. V. Lalberkhawpuimawia Thih hnu piah lam Pipute Suangtuahna Khawvel - 47 3. Denish Lalmalsawma Mizo Hlaa Poetic Technique kan hmuh \henkhatte- 71 4. -

The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:5 May 2015 ================================================================= The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. ================================================================= Abstract This paper discusses the problems of English Language Teaching and Learning in Mizoram, a state in India’s North-Eastern region. Since the State is evolving to be a monolingual state, more and more people tend to use only the local language, although skill in English language use is very highly valued by the people. Problems faced by both the teachers and the students are listed. Deficiencies in the syllabus as well as the textbooks are also pointed out. Some methods to improve the skills of both the teachers and students are suggested. Key words: English language teaching and learning, Mizoram schools, problems faced by students and teachers. 1. Introduction In order to understand the conditions and problems of teaching-learning English in Mizoram, it is important to delve into the background of Mizoram - its geographical location, the origin of the people (Mizo), the languages of the people, and the various cultures and customs practised by the people. How and when English Language Teaching (ELT) was started in Mizoram or how English is perceived, studied, seen and appreciated in Mizoram is an interesting question. Its remoteness and location also create problems for the learners. 2. Geographical Location Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:5 May 2015 Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram 173 Figure 1 : Map of Mizoram Mizoram is a mountainous region which became the 23rd State of the Indian Union in February, 1987. -

![Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0718/hripui-leh-literature-pandemic-and-literature-a-multidisciplinary-approach-may-27-29-2021-1550718.webp)

Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021

THREE DAY NATIONAL WEBINAR ON HRIPUI LEH LITERATURE [PANDEMIC AND LITERATURE : A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH] MAY 27-29, 2021 ORGANISeD BY DePArtMent of Mizo PACHHungA university College [A Constituent College of MizorAM university] ORGANIZING BODY PATRON Prof. H.Lalthanzara Principal, Pachhunga University College CO-PATRON CONveNeR CO-COORDINATORS enid H.Lalrammuani H.Laldinmawia Remlalthlamuanpuia Head & Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Dr. Zoramdinthara COORDINATOR Lalrotluanga Associate Professor Lalrammuana Sailo Assistant Professor Assistant Professor D r . L a l n u n p u i a Renthlei Assistant Professor Webinar Join Zoom Webinar@ 7:30 PM IST on May 27-29, 2021 For Registration WhatsApp Link Pachhunga Mizo Department Mizo Department : [email protected] Scan QR University College Instragram Pachhunga University [email protected] code for Channel mizo_department_puc College (Official) Whatsapp NI KHATNA (DAY ONe) MAY 27 (NINGANI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. vanlalnghaka Ralte B.Sc (Hons)., M.Sc, B.D., M.Th., D.Th. (Professor) Principal, Aizawl Theological College, Mizoram Keynote Speaker Prof. Malsawmliana Dr. Zothanchhingi Khiangte Department of History Assistant Professor, Department of English, Govt. T.Romana College, Aizawl, Mizoram Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Bodoland, India Topic : Hripui leh Mizo Literature – History Thlirna Atangin Topic :Literature Hring Chhuaktu Hripui (Pandemic and Mizo Literature – A Historical Approach) (Pandemic as a Source of Literature) NI HNIHNA (DAY TWO) MAY 28 (ZIRTAWP ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. H. vànlalruata Prof. vanlalnghaka Head, Christian Ministry & Communication Head, Department of Philosophy Aizawl Theological College North Eastern Hill University, Shillong Topic : Hripuiin Sakhuana A Nghawng Dan Topic : Hripui leh Mizona (Pandemic and Its Impact on Religious Practices) (Pandemic and Mizo Identity) NI THUMNA (DAY THRee) MAY 29 (INRINNI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Prof. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa KISSA-O-KALAM: THE SPEAKING PEN 2017 AN ANNUAL WORKSHOP ON WRITING AND CREATIVITY IN ENGLISH AND HINDI May 22-26, 2017, New Delhi Sahitya Akademi organized first-ever detailed event for children, the first edition of Kissa-O- Kalam: The Speaking Pen, an annual workshop for the young on creative writing in Hindi and English at the Akademi premises in New Delhi on May 22-26, 2017. This was a first of its kind initiative by the Akademi to sensitize our younger generations to our languages and literatures and to instill in them a love for the written word. This initiative, Kissa-O-Kalam: The Speaking Pen, envisaged as an annual affair with a focused interactive workshop as well as detailed individual activities held over five days encouraged and involved our children to participate and enjoy in the world of books and in the creative areas of reading and writing. Kissa-O-Kalam hopes to continue to carry forward the energy, creativity and results that were seen in this first installment in the coming years. This year, this 5-day session, held in the spacious and welcoming auditorium of the Akademi in New Delhi, from 22nd May to 26th May 2017 (Monday to Friday), was planned with a special focus to help children enjoy reading and writing both in prose and poetry, to begin to play with language, and to use language creatively and as a first step towards the creation of books. The workshop was titled Exploring Forms of Writing – Short Stories and Poetry. The workshop was opened to a final list of 50 students in the ages of 8 years to 16 years from across schools in the Delhi-NCR region. -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX History and Historiography of Mizoram Mizo History Association September 2018 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor : Dr. Rohmingmawii The Editorial Board shall not be responsible for authenticity of data, results, views, and conclusions drawn by the contributors in this Journal. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX September 2018 Editor Dr. Rohmingmawii Editorial Board Dr. Lalngurliana Sailo Dr. Samuel Vanlalthlanga Dr. Malsawmliana Dr. H. Vanlalhruaia Lalzarzova Dr. Lalnunpuii Ralte MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2017 – 2019) President : Prof. Sangkima Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna (Rtd) Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati Govt. Hrangbana College Patron : Prof. Darchhawna Kulikawn, Aizawl Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga ............................... Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo ................. Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana .....................Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga ...................Govt. Aizawl West College Mr. -

English Core Class – Xi

1 ENGLISH CORE CLASS – XI English Core Course (for a paper of 100 marks) DISTRIBUTION OF MARKS 1) Prose - 25 marks 2) Poetry - 25 marks 3) Supplementary Reader - 15 marks 4) Grammar & Composition a) Reading – Unseen Passages - 10 marks b) Writing - 10 marks c) Grammar & Usage - 15 marks Total = 100 marks I. Prose Pieces To Be Read: 1. ‗We‘re Not Afraid to Die … If We Can All Be Together‘ – by Gordon Cook and Alan Frost 2. The Ailing Planet: The Green Movements‘ Role – by Nani Palkhivala 3. Giant Despair – by John Bunyan 4. The Portrait of a Lady – by Khushwant Singh 5. The White Seal Adapted and Abridged from The Jungle Book – by Rudyard Kipling II. Poetry Pieces To Be Read: 1. The Kingfisher – by W. H. Davies 2. The Striders – by A. K. Ramanujan 3. To The Pupils of Hindu College – by H. L. V. Derozio 4. Childhood – by Marcus Nattan 5. In Paths Untrodden – by Walt Whitman Textbook Prescribed for Prose & Poetry:- Resonance Class XI Published by - Macmillan India Ltd., S. C. Goswami Road, Pan Bazar, Guwahati – 781001. III. Supplementary Reader Pieces To Be Read (Any two of the following pieces): 1. On Doing Nothing – by J. B. Priestly 2. Talking of Space – Report on Planet Three – by Arthur C. Clarke 3. A Devoted Son – by Anita Desai 2 Textbook Prescribed: Voices Classes XI & XII Published by - Macmillan India Ltd., S. C. Goswami Road, Pan Bazar, Guwahati – 781001. IV. Grammar & Composition The Prescribed Portions are: 1. Reading: Unseen Passages for (Comprehension and note taking in various topics and situations) 2.