Netball As a Space of Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Co-Curricular

Cultural and Artistic Opportunities International Club The International Club is a good chance to meet and mix with students from a range of cultures. Social activities, club meetings and fund raising are all part of this group's activities. The International Club is open to all students. Kapa Haka The school Kapa Haka group focuses on preparing performances for school events and regional competition. Practice is once a week at lunch time and this group is open to all students within the school. Manu Korero Each year four students are selected to represent the school at the Manu Korero regional Maori speech competitions. The students compete in either the senior or junior sections and will speak in either English or Maori. This is a wonderful opportunity for students to showcase their oratory expertise. The competitions are also a performance opportunity for our kapa haka group who support the speakers with a song as per Maori customs and protocols. Pasifika and Polyfest The school Pasifika group focuses on preparing performances for school events and regional competition. Whanau Hui Four times a year the whanau of the students are invited into the school. The whanau group is made up of the families of any students who identify as Maori, study Maori or are in the school kapa haka group. Opportunities in Debating and Public Speaking Debating A strong tradition of debating exists at Christchurch Girls' High School and several of our debaters have gone on to debate at the national and international level. There are plenty of opportunities for casual and competitive involvement in debating such as the Press Cup competitions and the Nga Kete Cup. -

Te Awamutu Courier, Thursday, November 10, 2011 Your Letters

Te Awamutu Courier 477 Sloane Street Te Awamutu Published Tuesday & Thursday THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2011 07 870 1688 8076097AA CELEBRATING 100 YEARS AS YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER CIRCULATED FREE TO ALL HOUSEHOLDS THROUGHOUT TE AWAMUTU AND SURROUNDING DISTRICTS. EXTRA COPIES 40c. 8422492AA BRIEFLY 11/11/11 Bianca beats best Te Awamutu and Districts Memorial Returned and Services Association is holding a service to mark Armistice Day, 2011 Prestigious award goes to Te Awamutu stylist tomorrow (November 11) at 11 am, at the Cenotaph on Anzac Team 7’s award winning Green. status has leapt ahead after Te Awamutu’s Bianca Karam- New Zealand has an RSA vice-president, Lou Whalley took out the prestigious ‘abundance of talented Brown will lead the service with Oceanic Hairdressing Master hair stylists the Oceanic Cr George Simmons Award. representing the Mayor. Prayers The event is the culmination Awards has once again will be led by Rev. Murray Olson of months of preparation and showcased the and the wreath laid by one of the practice for top stylists from extraordinary skills, oldest veterans, Alan Ambury. New Zealand and Australia, who Veterans are asked to parade this year came together in Mel- expertise and creativity with medals at the Cenotaph at bourne to battle for top honours. of registered hairstylists 10.45am (wet or fine). Bianca won the cut and the throughout New Following the service there conversion sections, and then Zealand. To be awarded will be a luncheon for the the overall title. veterans, their wives, partners She was also runner-up in the this title is a noteworthy and caregivers in the clubrooms Australian creative cut competi- accolade which will be closed until 3pm. -

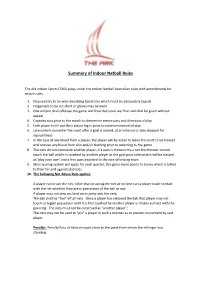

Summary of Indoor Netball Rules

Summary of Indoor Netball Rules The Ark Indoor Sports (TAIS) plays under the Indoor Netball Australian rules with amendments for centre rules. 1. No jewellery to be worn (wedding band only which must be adequately taped) 2. Fingernails to be cut short or gloves may be worn 3. One umpire shall officiate the game and their decisions are final and shall be given without appeal 4. Captains toss prior to the match to determine centre pass and direction of play 5. Each player to fill out their player log in prior to commencement of play 6. Late comers can enter the court after a goal is scored, at an interval or play stopped for injury/illness 7. In the case of any blood from a player, the player will be asked to leave the court to be treated and remove any blood from skin and/or clothing prior to returning to the game 8. The nets do not constitute another player, if a pass is thrown into a net the thrower cannot touch the ball until it is touched by another player or the goal post otherwise it will be classed as 'play your own' and a free pass awarded to the non-offending team 9. Skins scoring system will apply for each quarter, this gains more points to teams which is tallied to their for and against statistics. 10. The following Net Abuse Rule applies: A player can brush the net, other than brushing the net at no time can a player make contact with the net whether they are in possession of the ball or not; A player may not step on, land on or jump into the nets; The ball shall be “live” off all nets. -

WNC – June 2019

WAIUKU NETBALL CENTRE Meeting 3 MINUTES OF THE MANAGEMENT MEETING OF THE WAIUKU NETBALL CENTRE HELD IN THE PAVILION ON MONDAY 10 June AT 7.30 PM Present: Sharni Hunter (Chair), Yvette Burden, Rachel Browne-Cole, Eleanor Kitching, Judith Coe, Dania Lomas, Jacqui Misa, Claudette Lim, Jo Morriss, Shannon Bratton, Manda Leaver, Jessie Andrew-Robbie, Terri Johnston, Tracey Tamihere, Kym Cooper, Marion O’Neil, Tracey Philips, Tracey Margetts, Leiana Sloane, Leanne Campbell, Kim Voigt, Linda Simmons, Anne Walters, Rebecca Walters, Maree Wallace, Bronwyn Sloane Apologies: Tara Coe, Nicky Lipscombe, Debbie Lieder, Kim Marriner, Jo Barriball, Joneen Riddle, Janice Thomson, Sally Roden, Lorraine Hill (Please note that we did not take an official roll call due to not having the form on hand so apologies if anything is recorded in error, please advise Tara Coe if your attendance has been marked incorrectly) “that the apologies be accepted” Sharni Hunter / Kim Voigt Carried 1. Roll Call All clubs in attendance 2. Confirmation of Minutes RESOLVED that the minutes of the meeting held on Monday 6 May be adopted as a true and correct record of proceedings. Sharni Hunter / Tracey Phillips 3. Matters Arising At the last meeting the Sponsorship Committee asked to purchase tablecloths which was approved at the meeting but this was not reflected in the minutes. Leeanne Campbell enquired about the Pavilion Window & Door replacement. Nicky Lipscombe has looked into this and under our Insurance Policy our Excess is $2,500.00 therefore wouldn’t be justified under an Insurance claim. Replacement of the Film is $537.64 plus GST and to add a custom graphic would be an additional $420.75 plus GST. -

2 01 4 Netball Nsw Annu Al & Financial R E P O

2014 NETBALL NSW ANNUAL & FINANCIAL REPORT Our Mission Statement Netball NSW will provide to the NSW community sporting leadership and partnership through netball education and training programs, an extensive range of competitions and national success. It will be achieved through professional management and support to all administrative levels involved with the game so that these entities are financially viable. TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Report 2 CEO’s Report 4 Organisational Structure 5 Netball Central 6 Biennial Conference 8 Association Development Overview 11 Membership Figures 12-13 SPORT DEVELOPMENT Sport Development Overview 15 Schools Cup 16 Marie Little OAM Shield 17 Oceania Netball Cup 17 NSW umpires rule in 2014 18 NSW coaching stocks continue to rise 19 Regional State League 20 Going far and west to promote Netball 21 HIGH PERFORMANCE High Performance Overview 23-24 Creating a High Performance Pathway 25 State Teams 26-27 ANL Teams 28 SNA/SERNA 29 NSW Swifts 30-31 Commonwealth Games Gold 32 Catherine Cox: The fairy tale ending to a stellar career 33 COMPETITIONS AND EVENTS Competitions and Events Overview 35 State Championships 36 State Age Championships 38 DOOLEYS State League 40-41 Nance Kenny OAM Medal State League Player of the Year 41 Margaret Corbett OAM State League Coach of the Year 41 Court Craft Night Interdistrict 42 Netball NSW Masters 44 President’s Dinner 45 AWARD WINNERS 2014 Award Winners 47 2014 Hall of Fame Inductees 49 Netball NSW Hall of Fame 50 Life Members 50 Patrons 50 Anne Clark BEM Service Awards 51 Fullagar and Long Honoured 52 Broadbent and Sargeant Honoured 53 COMMERCIAL AND COMMUNICATIONS Commercial and Communications Overview 55-56 FINANCIAL REPORT Photography SMP Images, Fiora Sacco, Dave Callow, Netball Australia, Netball NSW, Michael Costa, South East Regional Netball Academy. -

On the Ball September 09 .Pub

CSNC PO Box 98 Bentleigh East 3165 Website: www.csnc.com.au Email: [email protected] On the Ball Issue 16 September, 2009 Caulfield South Netball Club e-Newsletter President’s Message Welcome to the September edi- tion of On The Ball. Hi everyone It has been a great month for netball, especially for those fol- It’s hard to believe September has arrived, and we know it is with the lowing the Australian Diamonds - AFL finals upon us! September of course means a break from netball what a great effort by the girls. with school holidays, so enjoy the few weeks off and be geared up for the final four matches of the season prior to finals (last game prior to Hard to believe that we are com- ing in to the home stretch for the finals is 7th November, 2009). Summer season - up to date lad- ders are listed on page 3. It was wonderful to see a number of Dads and their families enjoying the eggs and bacon on Saturday 5th September, 2009, for our Fa- Good luck to all teams for the remainder of the season. thers Day Breakfast. Thank you to everyone for your support! Karen Long The Committee has recently received a couple of queries regarding Editor the Club’s player / team allocation policy. This was discussed at length at the August CSNC Committee meeting and the CSNC Policy - Player/ Team Allocation has been developed. The Committee is finalising this policy and will distribute to all members for their information next month. Inside this Issue: If you have any suggestions or queries regarding the Club please don’t hesitate to give me a call on 0411 -

Mixed Pairs 1

MIXED PAIRS 1 - 3 MARCH CONTENTS Summerset Message 4 Bowls NZ Message 5 Daily Playing Programme 6 CONTENTS Club Directory & Travel Times 8 Tournament Officials 10 Conditions of Play 14 Code of Conduct 20 Prize Money 21 Teams 22 Summerset is proud to partner with Bowls New Zealand, for the third year running, to bring you the 2021 Summerset Nationals competitions. At Summerset we work hard to bring the best of life to residents in our retirement villages, including bowling greens at our villages and promoting this popular sport through our collaboration with Bowls New Zealand. We wish all competitors an enjoyable tournament and offer our congratulations to those that qualify for the latter stages of the events. FROM SUMMERSET FROM Julian Cook CEO Summerset Retirement Villages 4 ® Summerset is proud to partner with Bowls New Zealand, On behalf of Bowls New Zealand, it gives me great pleasure for the third year running, to bring you the 2021 Summerset to welcome all players, officials and supporters to Central Nationals competitions. Otago for the 2021 Summerset National Open Mixed Pairs Championship At Summerset we work hard to bring the best of life to residents in our retirement villages, including bowling I would like to acknowledge Summerset Retirement greens at our villages and promoting this popular sport Villages for their sponsorship of this event and of Bowls through our collaboration with Bowls New Zealand. New Zealand. We wish all competitors an enjoyable tournament and Thank you to Bowls Central Otago for hosting this event offer our congratulations to those that qualify for the latter and to Alexandra Bowling Club and the other host clubs stages of the events. -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, June 1, 2017

Te Awamutu COMPUTERS, NOTEBOOKS, SERVICE, SUPPORT, SOFTWARE, ACCESSORIES Published Tuesday & Thursday THURSDAY, JUNE 1, 2017 407 Sloane Street, Te Awamutu Couurier P 07 871 3837 | F 07 871 3807 Your community newspaper for over 100 years EXTRA COPIES 40c E [email protected] | www.computeraid.co.nz Phone books GOING, GOING... The 2017 Waipa Waitomo Local Phone/Yellow Books are available at the Courier Office. Office hours are Monday Pensioner housing selling to Habitat for Humanity to Thursday 8am to 5pm and Friday 8am to 4.30pm. Phone books will be available until the end of June. Winging way to Aussie Te Awamutu’s Emma Hughes flies across the Tasman tomorrow to represent New Zealand in the BMX Mighty 11’s Trans Tasman test series against Australia on June 10-11. Hughes, the NZ girls’ team No. 3 rider, will be accompanied by NZ No. 2 Grier Hall of Cambridge. The girls will be abroad for 10 days, billeted out with families in Eldersloe, South- West Sydney. Speaker at TA College Nathan Mikaere-Wallis is visiting TA College to speak about brain development and neuroscience and why children, teenagers and young adults behave the way they do. The presentation will be held at the Te Awamutu College Hall from 7.30pm to 9pm on Thursday, June 15 and is open to all parents, caregivers and any other interested people. A gold coin donation is appreciated. TC010617DT10 PALMER Street pensioner housing will be sold to Habitat for Humanity. Waipa District Council is to complex, will be required to munity on the proposal to sell more pensioner housing units in sell its Palmer Street pensioner maintain the complex specific- during March and April this our district,” he says. -

Netball Shooting Stats

Name: ____________________________ Date: ________________ Netball Shooting Stats LeBron James is an expert shooter from the Miami Heat basketball team. He is coming to Australia and New Zealand to run training camps on shooting technique. There is only funding for two players to attend the training camp. The organisers want to send players who have been inconsistent, so they can improve. Below are the shooting statistics for seven players over the past four seasons in the ANZ Championship. Player Team 2012 2011 2010 2009 Caitlin Bassett West Coast Fever 88.30% 88.80% 85.60% 84.00% Caitlin Thwaites Central Pulse 85.70% 81.30% 83.00% 84.10% Catherine Cox NSW Swifts 63.00% 77.60% 74.80% 81.40% Cathrine Latu Northern Mystics 97.50% 93.20% 91.70% 86.40% Irene van Dyk Waikato/BOP Magic 95.10% 92.00% 93.40% 93.50% Maria Tutaia Northern Mystics 76.10% 78.60% 80.30% 78.50% Paula Griffin Southern Steel 68.30% 79.70% 81.40% 79.70% Statistics retrieved from http://www.anz-championship.com/ Which two players are the most inconsistent and would benefit most from this training camp? Justify your answer. [page break] © NZQA Numeracy activity - Netball Shooting Stats: version 2013/1 Page 1 of 2 Information for tutor/teacher • Learners should be familiar with aspects of this problem, e.g. netball, ANZ Championship. • Refer to the requirements of the Numeracy unit standards if you wish to use evidence generated through this learning activity towards the standards. (The unit standards and their clarifications can be found on the NZQA website.) This problem needs to be part of a broader course of learning, in order for any evidence generated to be considered naturally occurring – and therefore valid for the Numeracy unit standards. -

A Brief History of Netball and Our Tactix Legacy

A Brief History of Netball and our Tactix Legacy What is Netball? “A new game for girls, about which a good deal will probably be heard in the course of the ensuing summer, is basket-ball. It has already swept the United States, completely eclipsing lawn tennis, and effectually nipping in the bud the threatened revival of croquet….The chief beauty of the game is its simplicity, and the fact that no expensive apparatus is required. Wherever two old baskets, a couple of clothes props, and a ball, are there can it be played.” (Otago Witness, 6 May 1897) The Game The game of netball is derived from the early development of basketball in the USA. The origin of basketball is traditionally credited to James Naismith, a 30-year-old Canadian immigrant to the USA, who in 1891, invented an indoor game for young men at the School for Christian Workers (later the YMCA) in Springfield, Massachusetts. The first games of what's now netball were played on a paddock between nine-a-side teams. The rules allowed three bounces, and throws from one end of the field to the other. Baskets were used for goals and after each goal, the ball was tipped out to restart play. Netball was first played in the UK in 1895 at Madame Ostenburg's College. In the first half of the 20th century, Netball's popularity continued to grow, with the game being played in many British Commonwealth countries. There were no standard rules at that time with both nine-a-side and five- a-side versions of the game. -

2016 Prime Ministers Scholarship Recipients Athlete

2016 PRIME MINISTERS SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENTS ATHLETE Athletics Aaron Booth, Amanda Murphy, Angela Petty, Lauren Bruce, Liam Malone, Lucy van Dalen, Anna Grimaldi, Ben Langton Burnell, Bradley Nicholas Souhgate, Nikki Hamblin, Rosa Mathas, Cameron French, Camille Buscomb, Flanagan, TeRina Keenan, Victoria Peeters, Eliza McCartney, Hamish Gill, Holly Robinson, William O'Neill, Zane Robertson, Zoe Hobbs James Sandilands, Joshua Hawkins, Basketball Finn Delany Boxing David Nyika Canoe Racing Briar McLeely, Britney Ford, Caitlin Ryan, Max Brown, Rebecca Cole, Teneale Hatton, Darryl Fitzgerald, Elise Legarth, Jaimee Lovett, Tobias Brooke, Zachary Franich, Zachary Jamie Banhidi, Kayla Imrie, Kim Thompson, Quickenden Kurtis Imrie, Lisa Carrington, Marty McDowell, Canoe Slalom Callum Gilbert, Finn Butcher, Luuka Jones, Michael Dawson Cycling Aaron Gate, Anton Cooper, Benjamin Stewart, Matthew Cameron, Matthew Dalton Bryony Botha, Cameron Karwowski, Codi Archibald, Natasha Hansen, Nina Wollaston, Merito, Daniel Franks, Elizabeth Steel, Emma Olivia Podmore, Philippa Sutton, Regan Cumming, Hannah Gumbley, Holly Gough, Rushlee Buchanan, Samuel Dakin, Edmondston, Holly Katrina White, Jaime Simon van Velthooven, Zachary Williams, Zoe Nielsen, Jeremy Presbury, Katherine Schofield, Fleming Lauren Ellis, Linda Villumsen, Luke Mudgway, Equestrian Abigail Colleen Douglas Long, Aleisha Collett, Renee Faulkner, Sarah Young, Tayla Mason Bonnie Farrant, Francesca da Souza-Silver, Football Abby Erceg, Aimee Phillips, Annalie Longo, Kirsty Yallop, Martine Puketapu, -

From Chronology to Confessional: New Zealand Sporting Biographies in Transition

From Chronology to Confessional: New Zealand Sporting Biographies in Transition GEOFF WATSON Abstract Formerly rather uniform in pattern, sporting biographies have evolved significantly since the 1970s, becoming much more open in their criticism of teammates and administrators as well as being more revealing of their subject’s private lives. This article identifies three transitional phases in the genre; a chronological era, extending from the early twentieth century until the 1960s; an indirectly confessional phase between the 1970s and mid 1980s and an openly confessional phase from the mid-1980s. Despite these changes, sporting biographies continue to reinforce the dominant narratives around sport in New Zealand. New Zealand sporting biographies have a mixed reputation in literary and scholarly circles. Often denigrated for their allegedly formulaic style, they have also been criticised for their lack of insight into New Zealand society.1 Representative of this critique is Lloyd Jones, who wrote in 1999, “sport hardly earns a mention in our wider literature, and … the rest of society is rarely, if ever, admitted to our sports literature.”2 This article examines this perspective, arguing that sporting biographies afford a valuable insight into New Zealand’s changing self- image and values. Moreover, it will be argued that the nature of sporting biographies themselves has changed significantly since the 1980s and that they have become much more open in their discussion of teammates and the personal lives of their subjects. Whatever one’s perspective on the literary merits of sporting biographies, their popular appeal is undeniable. Whereas the print run of most scholarly texts in New Zealand is at best a few thousand, sporting biographies consistently sell in the tens of thousands.