The Representation of Gender in Disney's Cinderella and Beauty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairy Tale Females: What Three Disney Classics Tell Us About Women

FFAAIIRRYY TTAALLEE FFEEMMAALLEESS:: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Spring 2002 Debbie Mead http://members.aol.com/_ht_a/ vltdisney?snow.html?mtbrand =AOL_US www.kstrom.net/isk/poca/pocahont .html www_unix.oit.umass.edu/~juls tar/Cinderella/disney.html Spring 2002 HCOM 475 CAPSTONE Instructor: Dr. Paul Fotsch Advisor: Professor Frances Payne Adler FAIRY TALE FEMALES: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Debbie Mead DEDICATION To: Joel, whose arrival made the need for critical viewing of media products more crucial, Oliver, who reminded me to be ever vigilant when, after viewing a classic Christmas video from my youth, said, “Way to show me stereotypes, Mom!” Larry, who is not a Prince, but is better—a Partner. Thank you for your support, tolerance, and love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Once Upon a Time --------------------------------------------1 The Origin of Fairy Tales ---------------------------------------1 Fairy Tale/Legend versus Disney Story SNOW WHITE ---------------------------------------------2 CINDERELLA ----------------------------------------------5 POCAHONTAS -------------------------------------------6 Film Release Dates and Analysis of Historical Influence Snow White ----------------------------------------------8 Cinderella -----------------------------------------------9 Pocahontas --------------------------------------------12 Messages Beauty --------------------------------------------------13 Relationships with other women ----------------------19 Relationships with men --------------------------------21 -

Racing Australia Limited

5 RANSOM TRUST (9)57½ WELLO'S PLUMBING CLASS 1 HANDICAP Owner: Mrs V L Klaric & I Cajkusic 1 4yo ch m Trust in a Gust - Love for Ransom (Red Ransom (USA)) KAYLA NISBET 1000 METRES 1.10 P.M. BLACK, GOLD MALTESE CROSS AND SEAMS, BLACK CAP Of $24,000.1st $12,280, 2nd $4,440, 3rd $2,300, 4th $1,200, 5th $750, 6th $550, 7th (W) 8 Starts. 1-0-1 $51,012 TECHFORM Rating 95 ' $500, 8th $500, 9th $500, 10th $500, Equine Welfare Fund $240, Jockey Welfare Fund Josh Julius (Bendigo) $240, Class 1, Handicap, Minimum Weight 55kg, Apprentices can claim, BOBS Silver Dist: 2:0-0-1 Wet: 3:1-0-1 Bonus Available Up To $9625, Track Name: Main Track Type: Turf 4-11 WOD 27Nov20 1100m BM64 Good3 H Coffey(4) 56 $10 This Skilled Cat 60 RECORD: 950 0-57.60 Emerging Power 1.0L, 1:04.30 5-12 ECHA 31Dec20 1200m BM58 Good4 D Stackhouse(1) 58.5 $4.60 Diamond FLYING FINCH (1) 61 Thora 59.5 3.2L, 1:10.75 1 9-10 BLLA 19Jan21 1112m BM58 Good3 M Walker(10) 60 $6 Arigato 61 9.8L, Owner: Dr C P Duddy & R A Osborne 1:05.10 5yo b or br g Redente - Lim's Falcon (Fasliyev (USA)) 3-8 COLR 05Aug21 1000m BM64 Soft7 D Bates(4) 56 $31 Bones 60.5 2.5L, MICHAEL TRAVERS 0:59.88 LIME, PALE BLUE YOKE, YELLOW SASH 10-11 MORP 21Aug21 1050m NMW BM70 Soft6 J Eaton(1) 54 $21 Lohn Ranger 54.5 (DW) 7 Starts. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

The Black and the White Bride: Dualism, Gender, and Bodies in European Fairy Tales

Jeana Jorgensen: The Black and the White Bride: Dualism, Gender, and Bodies in European Fairy Tales The Black and the White Bride: Dualism, Gender, and Bodies in European Fairy Tales Jeana Jorgensen Butler University* Fairy tales are one of the most important folklore genres in Western culture, spanning literary and oral cultures, folk and elite cultures, and print and mass media forms. As Jack Zipes observes: ‘The cultural evolution of the fairy tale is closely bound historically to all kinds of storytelling and different civilizing processes that have undergirded the formation of nation-states.’143 Studying fairy tales thus opens a window onto European history and cultures, ideologies, and aesthetics. My goal here is to examine how fairy-tale characters embody dualistic traits, in regard both to gender roles and to other dualisms, such as the divide between the mind and body, and the body’s interior and exterior (as characterized by the skin). These and other dualisms have been theorized from many quarters. As Elizabeth Grosz states: ‘Feminists and philosophers seem to share a common view of the human subject as a being made up of two dichotomously opposed characteristics: mind and body, thought and extension, reason and passion, psychology and biology.’144 Further, ‘Dichotomous thinking necessarily hierarchizes and ranks the two polarized terms so that one becomes the privileged term and the other its suppressed, subordinated, negative counterpart.’145 Thus, any discussion of dualisms is automatically also a discussion of power relations. This article begins by summarizing the trajectory of dualism in Western intellectual history and culture, including how dualism fits within folkloristic and feminist scholarship. -

Princess Stories Easy Please Note: Many Princess Titles Are Available Under the Call Number Juvenile Easy Disney

Princess Stories Easy Please note: Many princess titles are available under the call number Juvenile Easy Disney. Alsenas, Linas. Princess of 8th St. (Easy Alsenas) A shy little princess, on an outing with her mother, gets a royal treat when she makes a new friend. Andrews, Julie. The Very Fairy Princess Takes the Stage. (Easy Andrews) Even though Gerry is cast as the court jester instead of the crystal princess in her ballet class’s spring performance, she eventually regains her sparkle and once again feels like a fairy princess. Barbie. Barbie: Fairytale Favorites. (Easy Barbie) Barbie: Princess charm school -- Barbie: a fairy secret -- Barbie: a fashion fairytale -- Barbie in a mermaid tale -- Barbie and the three musketeers. Child, Lauren. The Princess and the Pea in Miniature : After the Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen. (Easy Child) Presents a re-telling of the well-known fairy tale of a young girl who feels a pea through twenty mattresses and twenty featherbeds and proves she is a real princess. Coyle, Carmela LaVigna . Do Princesses Really Kiss Frogs? (Easy Coyle) A young girl takes a hike with her father, asking many questions along the way about what princesses do. Cuyler, Margery. Princess Bess Gets Dressed. (Easy Cuyler) A fashionably dressed princess reveals her favorite clothes at the end of a busy day. Disney. 5-Minute Princess Stories. (Easy Disney) Magical tales about princesses from different Walt Disney movies. Disney. Princess Adventure Stories. (Easy Disney) A collection of stories from favorite Disney princesses. Edmonds, Lyra. An African Princess. (Easy Edmonds) Lyra and her parents go to the Caribbean to visit Taunte May, who reminds her that her family tree is full of princesses from Africa and around the world. -

World Dog Show Leipzig 2017

WORLD DOG SHOW LEIPZIG 2017 09.-12. November 2017, Tag 2 in der Leipziger Messe Schirmherrin: Staatsministerin für Soziales und Verbraucherschutz Barbara Klepsch Patron: Minister of State for Social Affairs and Consumer Protection Barbara Klepsch IMPRESSUM / FLAG Veranstalter / Promoter: Verband für das Deutsche Hundewesen (VDH) e.V. Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Telefon: (02 31) 5 65 00-0 Mo – Do 9.00 – 12.30/13.00 – 16.00 Uhr, Fr 9.00 – 12.30 Uhr Telefax: (02 31) 59 24 40 E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.vdh.de Chairmann/ Prof. Dr. Peter Friedrich Präsident der World Dog Show Secretary / Leif Kopernik Ausstellungsleitung Organization Commitee / VDH Service GmbH, Westfalendamm 174, 44141 Dortmund Organisation USt.-IdNr. DE 814257237 Amtsgericht Dortmund HRB 18593 Geschäftsführer: Leif Kopernik, Jörg Bartscherer TAGESEINTEILUNG / DAILY SCHEDULE FREITAG, 10.11.2017: Gruppe 5/ Group 5: Nordische Schlitten-, Jagd-, Wach- und Hütehunde, europäische und asiatische Spitze, Urtyp / Spitz and primitive types Gruppe 9 / Group 9: Gesellschafts- und Begleithunde / Companion and Toy Dogs TAGESABLAUF / DAILY ROUTINE 7.00 – 9.00 Uhr Einlass der Hunde / Entry for the Dogs 9.00 – 15.15 Uhr Bewertung der Hunde / Evaluation of the Dogs NOTICE: The World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 and the World Veteran Winner will get a Trophy. A Redelivery is not possible. HINWEIS: Die World Winner 2017, World Junior Winner 2017 und der World Veteranen Winner 2017 erhal- ten einen Pokal. Eine Nachlieferung ist nach der Veranstaltung nicht möglich. WETTBEWERBSRICHTER / JUDGES MAIN RING (WORLD DOG SHOW TAG 2) FREITAG, 10. NOVEMBER 2017 / FRIDAY, 10. NOVEMBER 2017 Junior Handling: Gerald Jipping (NLD) Zuchtgruppen / Best Breeders Group: Vija Klucniece (LVA) Paarklassen / Best Brace / Couple: Ramune Kazlauskaite (LTU) Veteranen / Best Veteran: Chan Weng Woh (MYS) Nachzuchtgruppen / Best Progeny Group: Dr. -

An Analysis of Figurative Language on Cinderella, Rumpelstiltskin, the Fisherman and His Wife and the Sleeping Beauty the Woods

AN ANALYSIS OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE ON CINDERELLA, RUMPELSTILTSKIN, THE FISHERMAN AND HIS WIFE AND THE SLEEPING BEAUTY THE WOODS BY CHARLES PERRAULT AND THE BROTHERS GRIMM Poppy Afrina Ni Luh Putu Setiarini, Anita Gunadarma University Gunadarma University Gunadarma University jl. Margonda Raya 100 jl. Margonda Raya 100 jl. Margonda Raya 100 Depok, 16424 Depok, 16424 Depok, 16424 ABSTRACT Figurative language exists to depict a beauty of words and give a vivid description of implicit messages. It is used in many literary works since a long time ago, including in children literature. The aims of the research are to describe about kinds of figurative language often used in Cinderella, Rumpeltstiltskin, The Fisherman and His Wife and The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods By Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm and also give a description the conceptual meaning of figurative language used in Cinderella, Rumpeltstiltskin, The Fisherman and His Wife and The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods By Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. The writer uses a descriptive qualitative method in this research. Keywords: Analysis, Figurative Language, Children. forms of communication, however some 1. INTRODUCTION children’s literature, explicitly story 1.1 Background of the Research employed to add more sensuous to Human beings tend to communicate each children. other through language. Likewise they Referring to the explanation use language as well as nonverbal above, the writer was interested to communication, to express their analyze figurative language used on thoughts, needs, culture, etc. Charles Perrault and The Brothers Furthermore, language plays major role Grimm’s short stories, therefore the to transfer even influence in a writer chooses this research entitled humankind matter. -

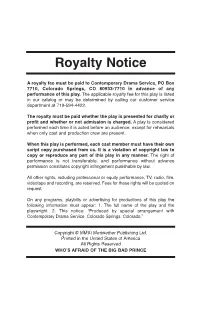

Royalty Notice

Royalty Notice A royalty fee must be paid to Contemporary Drama Service, PO Box 7710, Colorado Springs, CO 80933-7710 in advance of any performance of this play. The applicable royalty fee for this play is listed in our catalog or may be determined by calling our customer service department at 719-594-4422. The royalty must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is considered performed each time it is acted before an audience, except for rehearsals when only cast and production crew are present. When this play is performed, each cast member must have their own script copy purchased from us. It is a violation of copyright law to copy or reproduce any part of this play in any manner. The right of performance is not transferable, and performance without advance permission constitutes copyright infringement punishable by law. All other rights, including professional or equity performance, TV, radio, film, videotape and recording, are reserved. Fees for these rights will be quoted on request. On any programs, playbills or advertising for productions of this play the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play and the playwright. 2. This notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Contemporary Drama Service, Colorado Springs, Colorado.” Copyright © MMXI Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved WHOS AFRAID OF THE BIG BAD PRINCE Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Prince A two-act fairy tale parody/mystery by Craig Sodaro Meriwether Publishing Ltd. -

Rape in the Tale of Genji

SWEAT, TEARS AND NIGHTMARES: TEXTUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN HEIAN AND KAMAKURA MONOGATARI by OTILIA CLARA MILUTIN B.A., The University of Bucharest, 2003 M.A., The University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 ©Otilia Clara Milutin 2015 Abstract Readers and scholars of monogatari—court tales written between the ninth and the early twelfth century (during the Heian and Kamakura periods)—have generally agreed that much of their focus is on amorous encounters. They have, however, rarely addressed the question of whether these encounters are mutually desirable or, on the contrary, uninvited and therefore aggressive. For fear of anachronism, the topic of sexual violence has not been commonly pursued in the analyses of monogatari. I argue that not only can the phenomenon of sexual violence be clearly defined in the context of the monogatari genre, by drawing on contemporary feminist theories and philosophical debates, but also that it is easily identifiable within the text of these tales, by virtue of the coherent and cohesive patterns used to represent it. In my analysis of seven monogatari—Taketori, Utsuho, Ochikubo, Genji, Yoru no Nezame, Torikaebaya and Ariake no wakare—I follow the development of the textual representations of sexual violence and analyze them in relation to the role of these tales in supporting or subverting existing gender hierarchies. Finally, I examine the connection between representations of sexual violence and the monogatari genre itself. -

How Disney's Hercules Fails to Go the Distance

Article Balancing Gender and Power: How Disney’s Hercules Fails to Go the Distance Cassandra Primo Departments of Business and Sociology, McDaniel College, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] Received: 26 September 2018; Accepted: 14 November; Published: 16 November 2018 Abstract: Disney’s Hercules (1997) includes multiple examples of gender tropes throughout the film that provide a hodgepodge of portrayals of traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. Hercules’ phenomenal strength and idealized masculine body, coupled with his decision to relinquish power at the end of the film, may have resulted in a character lacking resonance because of a hybridization of stereotypically male and female traits. The film pivots from hypermasculinity to a noncohesive male identity that valorizes the traditionally-feminine trait of selflessness. This incongruous mixture of traits that comprise masculinity and femininity conflicts with stereotypical gender traits that characterize most Disney princes and princesses. As a result of the mixed messages pertaining to gender, Hercules does not appear to have spurred more progressive portrayals of masculinity in subsequent Disney movies, showing the complexity underlying gender stereotypes. Keywords: gender stereotypes; sexuality; heroism; hypermasculinity; selflessness; Hercules; Zeus; Megara 1. Introduction Disney’s influence in children’s entertainment has resulted in the scrutiny of gender stereotypes in its films (Do Rozario 2004; Dundes et al. 2018; England et al. 2011; Giroux and Pollock 2010). Disney’s Hercules (1997), however, has been largely overlooked in academic literature exploring the evolution of gender portrayals by the media giant. The animated film is a modernization of the classic myth in which the eponymous hero is a physically intimidating protagonist that epitomizes manhood. -

Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2013 Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films Grace DuGar Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation DuGar, Grace, "Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films" (2013). ETD Archive. 387. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR Bachelor of Arts in Political Science Denison University May 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by ____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Rachel Carnell ______________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________________________ James Marino ______________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________________ Gary Dyer ______________________________ Department & Date PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR ABSTRACT Disney fairy tale films are not as patriarchal and empowering of men as they have long been assumed to be. Laura Mulvey‘s cinematic theory of the gaze and more recent revisions of her theory inform this analysis of the portrayal of males and females in Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin.