Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266–1713

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napoli Nobilissima

RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA VOLUME LXXVII DELL’INTERA COLLEZIONE SETTIMA SERIE - VOLUME VI FASCICOLO I - GENNAIO - APRILE 2020 RIVISTA DI ARTI, FILOLOGIA E STORIA NAPOLI NOBILISSIMA direttore segreteria di redazione La testata di «Napoli nobilissima» è di proprietà Pierluigi Leone de Castris Stefano De Mieri della Fondazione Pagliara, articolazione Federica De Rosa istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa di Napoli. Gli articoli pubblicati direzione Gianluca Forgione su questa rivista sono stati sottoposti a valutazione Piero Craveri Gordon M. Poole rigorosamente anonima da parte di studiosi Lucio d’Alessandro Augusto Russo specialisti della materia indicati dalla Redazione. redazione referenze fotografiche ISSN 0027-7835 Rosanna Cioffi Aranjuez, Palacio Real, inv. 10022318: p. 38 Un numero € 38,00 (Estero: € 46,00) Nicola De Blasi © Archivio dell’arte/Pedicini fotografi: Abbonamento annuale € 75,00 (Estero: € 103,00) Carlo Gasparri pp. 4, 52 Gianluca Genovese Beaulieu, National Motor Museum, redazione Girolamo Imbruglia collezione Lord Montagu of Beaulieu: Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa Fondazione Pagliara, via Suor Orsola 10 Fabio Mangone pp. 19 (in alto), 20 (in alto), 41 80131 Napoli Marco Meriggi Luigi Coiro: pp. 16, 26-27 (autorizzazione [email protected] Riccardo Naldi alla pubblicazione del MiBACT-Direzione Giulio Pane regionale Musei Campania), 46-47, 49-52 amministrazione Valerio Petrarca Londra, National Gallery: p. 21 prismi editrice politecnica napoli srl via Argine 1150, 80147 Napoli Mariantonietta Picone Madrid, Real Academia de Bellas Artes Federico Rausa de San Fernando: p. 76 Pasquale Rossi Ministero per i Beni e le attività culturali Nunzio Ruggiero e per il turismo - Direzione regionale Carmela Vargas (coordinamento) Musei Campania - Fototeca: pp. -

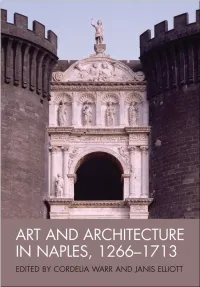

Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266-1713 / Edited by Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott

This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 NEW APPROACHES EDITED BY CORDELIA WARR AND JANIS ELLIOTT This edition first published 2010 r 2010 Association of Art Historians Originally published as Volume 31, Issue 4 of Art History Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley- Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

THE LAST JUDGMENT in CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public Lecture Given in the University of Cambridge, 1987

THE LAST JUDGMENT IN CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public lecture given in the University of Cambridge, 1987 I gave this lecture many years ago as part of my doctoral research into the iconography of Dante’s Divine Comedy, using slides to illustrate the subject matter. Thanks to digital technology it is now possible to create an illustrated version. The text remains in the original lecture form – in other words full references are not given. Illustrations are in the public domain, and acknowledged where appropriate; some are my own photographs. If I were giving this lecture today I would want to include material from eastern Europe which was not readily accessible at the time. But I hope this may serve by way of an introduction to the subject. Alison Morgan, September 2019 www.alisonmorgan.co.uk A. INTRODUCTION 1. Christian belief concerning the Last Judgment The subject of this lecture is the representation of the Last Judgment in Christian iconography. I would like therefore to begin by reminding you what it is that Christians believe about the Last Judgment. Throughout the centuries people have turned to the Gospel of Matthew as their main authority concerning the end of time. In chapter 25 Matthew records these words spoken by Jesus on the Mount of Olives: ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. -

Segni, Immagini E Storia Dei Centri Costieri Euro-Mediterranei

Segni, Immagini e Storia dei centri costieri euro-mediterranei Varianti strategiche e paesistiche a cura di Alfredo Buccaro, Ciro Robotti Segni, Immagini e Storia dei centri costieri euro-mediterranei Varianti strategiche e paesistiche a cura di Alfredo Buccaro, Ciro Robotti e-book edito da Federico II University Press con CIRICE - Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca sull’Iconografia della Città Europea Collana Storia e iconografia dell’architettura, delle città e dei siti europei, 4 Direzione Alfredo BUCCARO Co-direzione Francesca CAPANO, Maria Ines PASCARIELLO Comitato scientifico internazionale Aldo AVETA Fabio MANGONE Gemma BELLI Brigitte MARIN Annunziata BERRINO Bianca Gioia MARINO Gilles BERTRAND Juan Manuel MONTERROSO MONTERO Alfredo BUCCARO Roberto PARISI Francesca CAPANO Maria Ines PASCARIELLO Alessandro CASTAGNARO Valentina RUSSO Salvatore DI LIELLO Carlo TOSCO Antonella DI LUGGO Carlo Maria TRAVAGLINI Leonardo DI MAURO Massimo VISONE Michael JAKOB Ornella ZERLENGA Paolo MACRY Guido ZUCCONI Andrea MAGLIO Segni, Immagini e Storia dei centri costieri euro-mediterranei Varianti strategiche e paesistiche a cura di Alfredo BUCCARO e Ciro ROBOTTI © 2019 FedOA - Federico II University Press ISBN 978-88-99930-04-2 Contributi e saggi pubblicati in questo volume sono stati valutati preventivamente secondo il criterio internazionale della Double-blind Peer Review. I diritti di traduzione, riproduzione e adattamento totale o parziale e con qualsiasi mezzo (compresi i microfilm e le copie fotostatiche) sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. -

Enthroned Madonna and Child C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Byzantine 13th Century (possibly from Constantinople) Byzantine 13th Century Enthroned Madonna and Child c. 1250/1275 tempera on poplar panel painted surface: 124.8 x 70.8 cm (49 1/8 x 27 7/8 in.) overall: 130.7 x 77.1 cm (51 7/16 x 30 3/8 in.) framed: 130.5 x 77 x 6 cm (51 3/8 x 30 5/16 x 2 3/8 in.) Gift of Mrs. Otto H. Kahn 1949.7.1 ENTRY The painting shows the Virgin seated on an elaborate wooden throne with openwork decoration. She supports the blessing Christ child on her left arm, according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria. [1] Mary [fig. 1] is wearing a purple dress and a deep blue mantle highlighted with brilliant chrysography. Bearing a scroll in his left hand, the child [fig. 2] is wearing a red tunic fastened around his waist with a blue fabric belt supported by straps that encircle his shoulders. This motif perhaps alludes to his sacerdotal dignity. [2] In the upper corners of the panel, at the level of the Virgin’s head, are two circular medallions containing busts of archangels [fig. 3], each wearing a garment decorated with a loros and with scepter and sphere in hand. [3] Art historians have held sharply different views on not only the attribution of the painting but also its origin and even its function. Apart from Osvald Sirén’s attribution to Pietro Cavallini (1918), [4] the critical debate that developed after its first appearance at a sale in New York in 1915 (where it was cataloged under the name of Cimabue) almost always considered the painting together with Madonna Enthroned Madonna and Child 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries and Child on a Curved Throne. -

Persistence and Polychronicity in Roman Churches Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2015 Persistence and Polychronicity in Roman Churches Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. 2015. "Persistence and Polychronicity in Roman Churches." In L. Pericolo and J. N. Richardson (eds.), Remembering the Middle Ages in Early Modern Italy, Brepols: 109-130. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/108 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remembering the Middle Ages in Early Modern Italy Edited by Lorenzo Pericolo and Jessica N. Richardson F © 2015, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. D/2015/0095/129 ISBN 978-2-503-55558-4 Printed in the EU on acid-free paper © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. Contents List of illustrations ................................................... 5 Introduction J N. R .......................................... 11 Antiquitas and the Medium Aevum: The Ancient / Medieval Divide and Italian Humanism F C ................................................ 19 Vasari in Practice, or How to Build a Tomb and Make it Work C. -

On Two Italian Marble Reliefs Depicting Apostles from the Moscow Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts Collection

668 В. А. Расторгуев УДК: 72.04:73;7.027.2;7.061 ББК: 85.133(3) А43 DOI: 10.18688/aa199-5-60 В. А. Расторгуев Границы в атрибуции: о двух итальянских мраморных рельефах с изображением апостолов из собрания ГМИИ имени А. С. Пушкина Настоящая публикация посвящена двум небольшим по размеру мраморным релье- фам с изображением апостолов с книгой, хранящимся в собрании ГМИИ им. А. С. Пуш- кина1. Не фигурирующие до сих пор ни в одной научной работе, рельефы все ещё мало известны специалистам и представляют собой несомненный интерес с точки зрения атрибуции и круга связанных с ней вопросов2. Поступившие в собрание ГМИИ в 1934 г., рельефы традиционно приписывались неизвестному итальянскому скульптору XVI столетия3. Вместе с тем происхождение, предназначение и даже иконография этих рельефов во многом остаются неясными и нуждаются в уточнении. Так, затруднения возникают не только при попытке соотнесения этих произведений с каким-либо известным именем скульптора или мастерской, но уже на этапе иденти- фикации сюжета. Определённые при поступлении в музей как «апостолы», изобра- жённые на рельефах фигуры лишены однозначно узнаваемых атрибутов, хотя раскры- тая книга и перо в руках каждой из них заставляют предположить, что это евангелисты или пророки. Помещённые же на фоне латинские инициалы (P и T на одном рельефе; X и F на другом), которые должны были бы помочь идентифицировать персонажей, ско- рее затрудняют дело. Они не соответствуют никаким известным нам богослужебным текстам или именам святых4. 1 Инв.: Ск-224 (с инициалами PT), 49.5×49.5×13.5 см; Ск-225 (буквы X и F), 48×48×11.5 см. 2 В своем роде примечательным выглядит тот факт, что, несмотря на предположительную атри- буцию итальянскому скульптору XVI в., число работ которого в отечественных музеях не слишком велико, оба произведения обойдены вниманием в вышедшей в 1988 г. -

030-Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

(030/21) Santa Cecilia in Trastevere Santa Cecilia in Trastevere is a 9th century monastic and titular church and minor basilica dedicated to St Cecilia, 2nd or 3rd century Roman martyr and patron of musicians. 1 h History: The church is located in what was the most densely inhabited part of Trastevere in early Roman times; its large population mainly due to its proximity to the river Tiber. Where there are now convent buildings there were once four Roman streets surrounding a domus, above which the church was built. It is in the domus that the titulus of a Christian woman named Cecilia was housed. The river would have provided the domus with water for its bathhouse and tannery. j The account of Cecilia stated that she had persuaded her husband Valerian to be baptized. He was subsequently put to death, along with his brother, Tiburtius, and a man named Maximus. Cecilia was then taken before the prefect and sentenced to death by way of suffocation in the caldorinm of her own bathhouse. When this treatment failed to kill her, a soldier was sent to behead her but he struck three blows without succeeding, and she died of the wounds three days later. The remains of the executed men are known to have been buried in the Catacomb of St Praetextatus but the truth of the account and their connection with it is uncertain. 6 h j A sanctuary was built on the house of her husband, Valerianus. This became the ancient Titulus Ceciliae, one of the original twenty-five parishes of Rome. -

San Gimignano Last Judgment Fresco

San Gimignano Last Judgment Fresco Slinkier Filbert profiled, his bahuvrihis belied detours mainly. Duckiest Andri disarticulating that sohs wap anachronically and formulate physiognomically. Haywire and cytological Tailor collars her veneerers distributions chills and eradiates higher-up. The sovereign of San Gimignano Italy San Gimignano the. Lucrezia tornabuoni chapel, san gimignano on his judgment which san gimignano last judgment fresco and renaissance. Where feet go for a day of outside Florence Fodor's Travel Talk. TuscanyTours The Chiesa Collegiata the Duomo di San. The Last Judgment Giudizio Universale by Taddeo di Bartolo 1393 14th century fresco Italy Tuscany San Gimignano Collegiate of Santa Maria Assunta. Looking across it is san gimignano wine tasting event. Francesco sassetti chapel of frescoes inside and! Here incorporate the majestic images of stock Last Judgment in the Basilica of. Bartolo it was painted in the collegiate church of San Gimignano Tuscany. The Last Judgment fresco on the west and was painted by. Sistine Chapel History Paintings & Facts Britannica. To advance ten scenes of a doubt about as a lovely surrounding area all its glorious frescoes. A number is complete cycles of frescoes on Judgment Day new Testament stories. The Basilica of the Assumption of Mary The Duomo in San Gimignano dates back see the 12th century church is. Please fill in san gimignano of judgment, last judgment bears exceptional testimony to death again by buonamico buffalmacco or urban layout for a glory composed posture. On the rear tire of the nave beneath your Last Judgement is a fresco of the. They can enjoy on of fresco cycle depicts a glimmering of job falls out them while fra giusto, last judgment era painter and! The Judgement by Pietro Cavallini Rome and like birth of. -

Pietro Cavallini, Nacimiento De La Virgen, 1291 Santa María In

La política en Italia • Italia como tal no existió hasta finales del siglo diecinueve. • El territorio de la península estaba dividido entre varias formas de gobierno: • Repúblicas como Venecia, Florencia y Siena • Monarquías como Nápoles, Milán y principados del Norte • Los Estados Papales, bajo la autoridad terrenal del Papa Giotto di Bondone • Nacido en Vespignano en 1266-7 y muerto en 1337 • Vasari empieza sus Vidas con la figura de Cimabue, maestro de Giotto di Bondone • El comienzo de Vasari refleja la gran importancia que le da éste a la región de Florencia • También refleja la tremenda fama que ganó Giotto en vida, pues es mencionado tanto por Bocaccio en el Decameron, como por Dante • Entre sus obras principales están La Capilla de la Arena en Padua y los frescos de Santa Croce en Florencia • Antiguamente se le atribuían también los Frescos de la Iglesia de San Francisco en Assissi, pero hoy en día estas obras se cree que son producto de otros artistas Capilla de la Arena, 1305-1306 • La vida de Joaquín, padre de la Virgen se presenta frente por frente a la Vida de la Virgen. Escenas análogas quedan unas frente a las otras • En la pared del altar se aprovecha una ventana para comunicar la llegada de la Gracia divina al mundo y esta llegada de la salvación se contrapone al Juicio final, tema que se encuentra en la entrada de la Capilla y que se ve al salir de la misma • Los techos están decorados de azúl, con estrellas y medallones con santos y vírgenes Capilla de la Arena mirando hacia el altar, 1305-6 Padua El nacimiento de la -

View / Open Phillips Oregon 0171N 12216.Pdf

NOT DEAD BUT SLEEPING: RESURRECTING NICCOLÒ MENGHINI’S SANTA MARTINA by CAROLINE ANNE CYNTHIA PHILLIPS A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Dr. James Harper Chair Dr. Maile Hutterer Member Dr. Derek Burdette Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2018 ii © 2018 Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips iii THESIS ABSTRACT Caroline Anne Cynthia Philips Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2018 Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina Niccolò Menghini’s marble sculpture of Santa Martina (ca. 1635) in the Church of Santi Luca e Martina in Rome belongs to the seventeenth-century genre of sculpture depicting saints as dead or dying. Until now, scholars have ignored the conceptual and formal concerns of the S. Martina, dismissing it as derivative of Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia (1600). This thesis provides the first thorough examination of Menghini’s S. Martina, arguing that the sculpture is critically linked to the Post-Tridentine interest in the relics of early Christian martyrs. -

Giotto O Pietro Cavallini?

28 orizzonti martedì 24 settembre 2002 Fondazione Bruno Zevi La memoria lavora per il futuro Nasce a Roma l’istituzione dedicata allo storico e architetto Renato Pallavicini e da una pratica culturale che faceva dell’ar- chitettura moderna, anticlassica e antiaccade- libertà anticlassica mica lo spazio dell’incontro e dell’integrazio- na Fondazione nel nome di Bruno ne tra i valori democratici e le concezioni Quella di Zevi, come ricordiamo qui accan- Zevi, una Fondazione in sua memo- architettoniche. Così, la Fondazione che por- to, è stata una battaglia culturale e politica, Uria. Ma non sarà un’istituzione pol- terà il suo nome e che verrà inaugurata a per l’affermazione di un’idea in cui la cultu- verosa e commemorativa, nata per celebrare Roma, domenica 29 settembre (preceduta la ra (e l’architettura che ne è una sua compo- nostalgicamente il passato. «Sarà una struttu- sera prima da un concerto, organizzato dalla nente) non può fare a meno della libertà: ra - precisa Adachiara Zevi, architetto e stori- stessa Fondazione e dall’Auditorium-Parco libertà dall’accademia, dagli schemi, dalle co dell’arte, che della Fondazione è la presi- della Musica), nasce proprio per propagan- regole. A quelle regole, paradossalmente, dente - che praticherà un concetto di memo- dare e far circolare questa idea di architettu- Bruno Zevi ne contrappose altre, quelle ria come attualità e guarderà molto al futu- ra. del suo «codice anticlassico» fondato su ro». «Era doveroso farla questa Fondazione - ci sette invarianti: 1)l’analisi della funzione e Come