Support for Electoral Law Reforms in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

EISA Technical ASSESSMENT TEAM REPORT UGANDA The

EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT i EISA TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT TEAM REPORT UGANDA THE UGANDAN PRESIDENTIAL AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS OF 18 FEBRUARY 2011 ii EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT iii EISA TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT MISSION REPORT UGANDA THE UGANDAN PRESIDENTIAL AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS OF 18 FEBRUARY 2011 2012 iv EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT Published by EISA 14 Park Rd, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: 27 11 381 6000 Fax: 27 11 482 6163 Email: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 978-1-920446-36-9 © EISA 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2012 EISA strives for excellence in the promotion of credible elections, participatory democracy, human rights culture, and the strengthening of governance institutions for the consolidation of democracy in Africa. EISA Technical Assessment Mission Report, No. 41 EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT v CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Acronyms and Abbreviations viii Executive Summary ix Terms of Reference of the EISA Technical Assessment Team x Methodology of the Technical Assessment Team xii The EISA Approach to Election Observation xiii 1. Historical and Political Overview 1 1.1 Historical background 1 1.2 Political and electoral background 3 1.3 Elections in Uganda 4 2. Constitutional, Legal & Institutional Framework 7 2.1 Constitutional and legal framework 7 2.2 Electoral framework 9 2.3 The Electoral Commission of Uganda 17 2.4 Other institutions involved in elections 19 2.5 The electoral system 19 2.6 Challenges 20 3. -

Nozzom Newsletter Issue

NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #29 - December 2017 Moving… Foreword Contents Welcome to our new issue of Nozzom, where we share with you our events and projects as well as our future plans and outlook on happenings and opportunities. Maturity does not necessarily come with age, but with experience. As is the case with sentient beings, organizations have a lifecycle in 04 which they themselves experience various stages of learning, developing, adapting, and striving towards being better. With maturity comes NOZZOM NEWSLETTER ISSUE #29 responsibility: the responsibility to look inwards, at the way business is done and how it can develop itself to improve; and outwards, at how Agility in ENAL the organization can support and further contribute to the development of the society in which it finds itself. Chairman Recognizing where we are currently at, Giza Systems’ goal is to self-develop, learn from our experiences, and mature as a whole, with reference Shehab ElNawawi to our business and our community alike. We are entering a ‘regeneration’ phase that surpasses adapting to our surroundings. Quintessentially, it is about striving to do better and be better. Managing Editor Just a few highlights on what you can expect in this issue of Nozzom: Lara Shawky New Leaps • Giza Systems Implements 50,000 Smart Meters in North Cairo Zone in Saudi 15 • Fire Alarm and Detection Systems Implementation in Al Masah Capital Complex, New Cairo Internatinal Convention and Exhibition Center, Mzizima Tower Complex, Meliá Hotels International Creative & Art Director -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Un Reform Milestones in Uganda

UN REFORM MILESTONES IN UGANDA 2 UN REFORM MILESTONES IN UGANDA On 1 January 2019, the • Clear and more robust lines of accountability, from UN country United Nations pivoted to teams to host governments, from the a new era of UN Reforms Resident Coordinator to the Secretary- General, as well as between Resident for the UN development Coordinators and heads of UN entities system, exactly three years at the country level. after the 2030 Agenda for • United Nations Development Assistance Framework (now renamed Sustainable Development the United Nations Sustainable took effect. With these Development Cooperation Framework) as “the most important instrument for changes the United planning and implementation of the UN development activities at country Nations development level in support of the implementation system is expected to of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable become stronger, have a Development.” better-defined collective • A new generation of UN Country Teams, comprised of representatives from identity as a trusted, Government, Development Partners, Civil Society and the Private sector. reliable, accountable The new generation UNCT meets and effective partner to periodically and members of the civil society participate in these meetings countries for achieving the including the most recent one held last 2030 Agenda and one that week. Member States can invest • A shift in donor funding towards more predictable and flexible resources, that in and rely on, because allow, in turn, the UN development they understand and system to tailor its support, enhance results delivery, and provide greater support what it does, what transparency, accountability and it can deliver on, and how it visibility for resources entrusted to the system. -

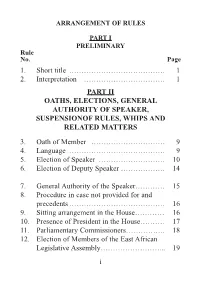

1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY of SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS and RELATED MATTERS 3

ARRANGEMENT OF RULES PART I PRELIMINARY Rule No. Page 1. Short title………………………………… 1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY OF SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS AND RELATED MATTERS 3. Oath of Member ………………………… 9 4. Language ………………………………… 9 5. Election of Speaker ……………………… 10 6. Election of Deputy Speaker ……………… 14 7. General Authority of the Speaker………… 15 8. Procedure in case not provided for and precedents………………………………… 16 9. Sitting arrangement in the House………… 16 10. Presence of President in the House………. 17 11. Parliamentary Commissioners……………. 18 12. Election of Members of the East African Legislative Assembly……………………... 19 i Rule No. Page 13. Election of Members of Pan African Parliament………………………………… 20 14. Role and functions of the Leader of the Opposition ………………………… 20 15. Whips……………………………………… 21 16. Suspension of Rules ……………………… 23 PART III MEETINGS, SITTINGS AND ADJOURNMENT OF THE HOUSE 17. Meetings ………………………………… 24 18. Emergency meetings……………………… 24 19. Sittings of the House……………………… 24 20. Suspension of sittings and recall of House from adjournment ………………… 25 21. Request for recall of Parliament from recess 26 22. Public holidays …………………………… 26 23. Sittings of the House to be public………... 26 24. Quorum of Parliament …………………… 27 PART IV ORDER OF BUSINESS 25. Order of business ………………………… 29 26. Procedure of Business …………………… 31 ii Rule No. Page 27. Order Paper to be sent in advance to Members ………………………………… 32 28. Statement of business by Leader of Government Business …………………… 33 29. Weekly Order Paper ……………………… 33 PART V PETITIONS 30. Petitions…………………………………… 34 PART VI PAPERS 31. Laying of Papers ………………………… 37 32. Mode of Laying of Papers………………… 37 PART VII PRESENTATION OF REPORTS OF PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATIONS ABROAD 33. -

Tenure Security, Land Institutions and Economic Activity in Uganda

DIIS WORKING PAPER DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:03 Titel Undertitel LandForfatter Tenure under Transition – Tenure Security, Land Institutions andDIIS Economic Working PaperActivity 2012:XX in Uganda DIIS Working Paper 2013:03 Helle Munk Ravnborg, Bernard Bashaasha, Rasmus Hundsbæk Pedersen, Rachel Spichiger and Alice Turinawe WORKING PAPER WORKING 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:03 HELLE MUNK RAVNBORG Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] BERNARD BASHAASHA RASMUS HUNDSBÆK PEDERSEN RACHEL SPICHIGER ALICE TURINAWE The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Michael Kidoido and Sarah Alobo who took part in the qualitative interviews and coordinated and supervised the questionnaire survey upon which this report is based. The authors also wish to acknowledge the useful comments provided during the study from Stephen Ajalu, Royal Danish Embassy, Kampala, and Rikke Brandt Broegaard, DIIS. This report forms part of a study of the linkages between land and property rights and economic behaviour in Uganda, commissioned by the Royal Danish Embas- sy in Kampala, Uganda. The study has been conducted in collaboration between researchers from Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen, Denmark, and Makerere University (MAK), Kampala, Uganda. DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS -

Briefing Note on the Uganda UNSDCF

THE UNITED NATIONS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION FRAMEWORK FOR UGANDA (2021-2025) BRIEFING NOTE UNITED NATIONS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION FRAMEWORK FOR UGANDA 2021-2025 Brief Outline and Chronology of Key Milestones The UN General Assembly Resolution 72/279 on the repositioning of the UN Development System, positions the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) as the single most important UN country planning instrument in support of the 2030 Agenda. The current UN Development Assistance Framework for Uganda (UNDAF, 2016-2020) has ended on 31st December 2020. The United Nations Country Team in Uganda in partnership with Government and non-state stakeholders through the National Task Team have developed the new United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework for Uganda (2021-2025) launched on 9th September 2020 by the President of Uganda and RC/UNCT. The UNSDCF is supported by the Joint Statement of Accountability signed by the Prime Minister, National Planning Authority Chair, UN Resident Coordinator and 29 UN entities on 2nd September 2020. With SDGs at its core, the Cooperation Framework is closely aligned to the National Development Plan III and Uganda’s National Vision 2040 and will be implemented by 29 UN entities through three Strategic Priorities: 1) Transformative and Inclusive Governance; 2) Shared Prosperity in a Healthy Environment; and 3) Human Well-being and Resilience. The UN General Assembly Resolution 72/279 on the repositioning of the UN development system, positions the UNSDCF as the single most important UN country planning instrument in support of the 2030 Agenda. The UN Resident Coordinator and UN entities adhere to the individual and mutual accountabilities stipulated in the Management and Accountability Framework. -

State of the Environment Report for Uganda 2006/2007

STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR UGANDA 2006/2007 Copy right @ 2006/07 National Environment Management Authority All rights reserved. National Environment Management Authority P.O Box 22255 Kampala, Uganda http://www.nemaug.org [email protected] Publication: This publication is available both in hard copy and on the website of the National Environment Management Authority, www.nemaug.org. A charge will be levied according to the pricing policy in the authority. Suggested citation: National Environment Management Authority, 2006/07, State of Environment Report for Uganda, NEMA, Kampala. 332pp. This publication is available at the following libraries: National Environment Management Authority, Library. National Environment Management Authority Store. District Environment Offices. District Environment Resource Centers Public libraries. Makerere University library Kyambogo University library. Editor in chief: Mrs Kitutu Kimono Mary Goretti Copy editing: Dr Kiguli Susan and Mr Merit Kabugo Authors: Ema Consult Dr. Moyini Yakobo (Team leader). Review team: Dr. Aryamanya Mugisha Henry National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Telly Eugene Muramira National Environment Management Authority. Dr. Festus Bagoora National Environment Management Authority. Mrs. Mary Goretti Kitutu Kimono National Environment Management Authority. Mr. George Lubega National Environment management Authority. Mr. Francis Ogwal National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Ronald Kaggwa National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Margaret Lwanga National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Firipo Mpabulungi National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Elizabeth Mutayanjulwa National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Margaret Aanyu National Environment Management Authority. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is again honored to present another edition of the State of the Environment Report for Uganda. This is the seventh report since the first one was published in 1994. -

ECFG-Uganda-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of two parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the Uganda ECFG foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment (Photos a courtesy of Pro Quest 2011). Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Uganda, focusing on unique cultural features of Ugandan society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Kampala, Uganda, 2016 Produced By: Lars Schoebitz, Eawag/Sandec Charles B

SFD Promotion Initiative Kampala Uganda Final Report This SFD Report was prepared through desk-based research by Sandec (the Department of Sanitation, Water and Solid Waste for Development) at Eawag (the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology) as part of the SFD Promotion Initiative. Collaborating partners Date of production: 06.06.2016 Last update: 11.07.2016 Kampala Executive Summary Produced by: Eawag/Sandec Uganda SFD Report Kampala, Uganda, 2016 Produced by: Lars Schoebitz, Eawag/Sandec Charles B. Niwagaba, Makerere University Linda Strande, Eawag/Sandec ©Copyright All SFD Promotion Initiative materials are freely available following the open-source concept for capacity development and non-profit use, so long as proper acknowledgement of the source is made when used. Users should always give credit in citations to the original author, source and copyright holder. This Executive Summary and SFD Report are available from: www.sfd.susana.org Last Update: 06/06/2016 I Kampala Executive Summary Produced by: Eawag/Sandec Uganda 1. The Diagram Note: Percentages do not add up to 100 due to rounding 2. Diagram information dry seasons between December and March, and June and July (KSMP, 2004). The Shit Flow Diagram (SFD) was developed through desk-based research by Sandec 64% of the city is classified as residential area. (Sanitation, Water and Solid Waste for Wakiso and Mukono Districts surround Development) of Eawag (the Swiss Federal Kampala and have a population of 1,997,418 Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology) (Wakiso) and 596,804 (Mukono) (UBOS, and CEDAT (College of Engineering, Design 2016). It is estimated that the population Art and Technology) at Makerere University. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS An exploration of the post-conflict integration of children born in captivity living in the Lord’s Resistance Army war-affected areas of Uganda by EUNICE AKULLO Thesis for the degree of a Doctor of Philosophy in Politics and International Relations [NOVEMBER, 2019] UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Thesis for the degree of a Doctor of Philosophy in Politics and International Relations An exploration of the post-conflict integration of children born in captivity living in the Lord’s Resistance Army war-affected areas of Uganda EUNICE AKULLO This thesis explores the extent to which existing national transitional justice policy frameworks structuring reintegration and integration interventions enable the effective or successful integration of children born in captivity (CBIC) in Uganda.