1 Chapter 2: a Short History of Fairtrade Certification Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2009

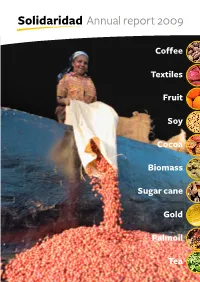

Annual report 2009 Solidaridad Coffee Annual report 2009 Textiles Fruit Soy C0coa Biomass Sugar cane Gold Palmoil Tea Solidaridad Network Statutory principles Solidaridad Solidaridad Foundation was established on 15 June 1976 Solidaridad’s organizational structure is going through and has its office in Utrecht. Solidaridad sees itself as an important change process: the transformation into part of the Christian ecumenical tradition which works an international network organization. This innovation to achieve economical, political and cultural justice, is necessary for shaping the future of our international and the care of creation. With the guiding principles cooperation. of peace and freedom, Solidaridad seeks working relationships with partners that strive to achieve justice p 8 and sustainability grounded in their own religious and cultural traditions. Solidaridad’s objective is to support organizations in developing countries that seek to structurally combat poverty. Solidaridad seeks to achieve this aim through: – Strengthening producer organizations and civil society organizations in developing countries that are working on the sustainable development of their economy. – Involving companies, financial institutions and investors in developing supply chains with added value for producers, created through Fair Trade and corporate social responsibility. – Involving citizens and consumers in and creating a support base in churches and society for sustainable Textiles economic development through providing informa- Bigger brands and -

Fair Trade USA® Works of Many Leading the with Brands And

• FAIR TRADE USA • Fair Trade USA® CAPITAL CAMPAIGN FINAL REPORT 1 It started with a dream. What Visionary entrepreneur and philanthropist Bob Stiller and his wife Christine gave us a if our fair trade model could It Started spectacular kick-off with their $10 million reach and empower even more matching leadership gift. This singular people? What if we could impact gift inspired many more philanthropists with a and foundations to invest in the dream, not just smallholder farmers giving us the chance to innovate and and members of farming expand. Soon, we were certifying apparel Dream and home goods, seafood, and a wider cooperatives but also workers range of fresh produce, including fruits on large commercial farms and and vegetables grown on US farms – something that had never been done in the in factories? How about the history of fair trade. fishers? And what about farmers • FAIR TRADE USA • In short, the visionary generosity of our and workers in the US? How community fueled an evolution of our could we expand our movement, model of change that is now ensuring safer working conditions, better wages, and implement a more inclusive more sustainable livelihoods for farmers, philosophy and accelerate the workers and their families, all while protecting the environment. journey toward our vision of Fair In December 2018, after five years and Trade for All? hundreds of gifts, we hit our Capital • FAIR TRADE USA • That was the beginning of the Fair Trade Campaign goal of raising $25 million! USA® Capital Campaign. • FAIR TRADE USA • This report celebrates that accomplishment, The silent phase of the Capital Campaign honors those who made it happen, and started in 2013 when our board, leadership shares the profound impact that this team and close allies began discussing “change capital” has had for so many strategies for dramatically expanding families and communities around the world. -

Public Procurement, Fair Trade Governance and Sustainable

Fair Trade Governance, Public Procurement and Sustainable Development: A case study of Malawian rice in Scotland This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Alastair M. Smith Department of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University May 2011 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i ii Abstract/Summary This thesis provides an account of the way in which meaning associated with the term ‘fair trade’ is negotiated within a number of discrete, yet interrelated communities, in a way which influences stakeholder understanding of the concept – and as a result, structures the way in which public procurement strategies integrate fair trade governance into their operation. Building from the identification of ‘fair trade’ governance as a means to embed the intra- generational social justice concerns of sustainable development within the public procurement system, the thesis investigates how the ambiguous meaning of fair trade is reconciled in discourse and practice. -

FISCAL 2012 ANNUAL REPORT Fiscal 2012 Annual Publications

FISCAL 2012 ANNUAL REPORT Fiscal 2012 annual publications FISCAL 2012 ANNUAL REPORT SUMMARY Message from Michel Landel, Chief Executive Officer, Sodexo page 2 Our Group PROFILE page 6 HISTORY page 11 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE page 13 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE page 22 Our strategy THE FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF OUR DEVELOPMENT page 34 OUR AMBITION page 39 Our Quality of Life Services OUR ON-SITE SERVICES page 42 OUR BENEFITS AND REWARDS SERVICES page 89 OUR PERSONAL AND HOME SERVICES page 101 Glossary page 106 Fiscal 2012 annual publications Annual Report Message from Michel Landel, Sodexo’s Chief Executive Officer. November 8, 2012 In a very difficult economic environment, I am pleased to confirm that Sodexo continues to be a growth company, demonstrating the effectiveness of our strategy and the strength of our unique positioning as an integrator of Quality of Life services. During the just completed fiscal year, we have maintained the investments necessary to support Sodexo’s continued transformation. In a complicated economic environment, Sodexo’s growth continues In 2012, the global economic climate remained particularly troubled: Europe appears locked in a vicious recessionary circle, the U.S. is still vulnerable under the weight of its debt and the so-called “emerging” countries have felt the effects of the overall slowdown. Despite this uncertain environment, Sodexo has continued to grow and is maintaining its medium-term objectives. We can be confident in our Group’s future for three main reasons: Our positioning is at the heart of societal change Services are driving development in modern societies. They play an increasingly important role in economic activity, employment and responding to individual needs. -

2014 Annual Report I

2014 ANNUAL REPORT I. Table of Contents I. Table of Contents 2 II. Letter from the President 3 III. About WFTO 4 A global network of Fair Trade Organisations 4 Our vision and mission 4 A membership organization 5 The Goals of WFTO 5 Credibility & identity 5 Learning 5 Voice 5 Market access 5 Capability 5 I V. Our achievements and activities 6 a. Credibility and Identity 6 b. Learning 7 c. Market Access 9 d. Voice 10 e. Capability 13 V. The WFTO enlarged family: WFTO Regions 16 VI. Our supporters 18 VII. ANNEXES to 2014 Annual Report 18 Financial Overview for 2014 18 Balance Sheet 2014 18 Income and Expenditure 19 List of WFTO members, as of 31 December 2014. 20 List of WFTO individual associates, as of 31 December 2014. 27 2 - 2014 WFTO Annual Report I. Letter from the President Dear WFTO members, provisional Member, Associates and Fair Trade friends, Last year I had the chance prove the ‘FTO identity’ and the compliance of WFTO to encounter again in my members with FT principles. By the end of 2014, more travels around the globe than 2/3 of our member had started their GS process. countless enthusiastic This lets us hope that soon most of our members will promoters of Fair Trade be Guaranteed FTO. Guaranteed members are allowed (FT) principles and Fair to place the WFTO product label on their products and Trade products. I realized many members are asking how the label will be promot- once more that after sev- ed to generate sales. -

Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges

LAURA T. RAYNOLDS Professor, Department of Sociology, Director, Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Colorado State University Email: [email protected] Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges ABSTRACT Fairtrade International certification is the primary social certification in the agro-food sector in- tended to promote the well-being and empowerment of farmers and workers in the Global South. Although Fairtrade’s farmer program is well studied, far less is known about its labor certification. Helping fill this gap, this article provides a systematic account of Fairtrade’s labor certification system and standards and com- pares it to four other voluntary programs addressing labor conditions in global agro-export sectors. The study explains how Fairtrade International institutionalizes its equity and empowerment goals in its labor certifica- tion system and its recently revised labor standards. Drawing on critiques of compliance-based labor stand- ards programs and proposals regarding the central features of a ‘beyond compliance’ approach, the inquiry focuses on Fairtrade’s efforts to promote inclusive governance, participatory oversight, and enabling rights. I argue that Fairtrade is making important, but incomplete, advances in each domain, pursuing a ‘worker- enabling compliance’ model based on new audit report sharing, living wage, and unionization requirements and its established Premium Program. While Fairtrade pursues more robust ‘beyond compliance’ advances than competing programs, the study finds that, like other voluntary initiatives, Fairtrade faces critical challenges in implementing its standards and realizing its empowerment goals. KEYWORDS fair trade, Fairtrade International, multi-stakeholder initiatives, certification, voluntary standards, labor rights INTRODUCTION Voluntary certification systems seeking to improve social and environmental conditions in global production have recently proliferated. -

1 Doherty, B, Davies, IA (2012), Where Now for Fair Trade, Business History

Doherty, B, Davies, I.A. (2012), Where now for fair trade, Business History, (Forthcoming) Abstract This paper critically examines the discourse surrounding fair trade mainstreaming, and discusses the potential avenues for the future of the social movement. The authors have a unique insight into the fair trade market having a combined experience of over 30 years in practice and 15 as fair trade scholars. The paper highlights a number of benefits of mainstreaming, not least the continued growth of the global fair trade market (tipped to top $7 billion in 2012). However the paper also highlights the negative consequences of mainstreaming on the long term viability of fair trade as a credible ethical standard. Keywords: Fair trade, Mainstreaming, Fairtrade Organisations, supermarket retailers, Multinational Corporations, Co-optation, Dilution, Fair-washing. Introduction Fair trade is a social movement based on an ideology of encouraging community development in some of the most deprived areas of the world1. It coined phrases such as “working themselves out of poverty” and “trade not aid” as the mantras on which growth and public acceptance were built.2 As it matured it formalised definitions of fair trade and set up independent governance and monitoring organisations to oversee fair trade supply-chain agreements and the licensing of participants. The growth of fair trade has gone hand-in-hand with a growth in mainstream corporate involvement, with many in the movement perceiving engagement with the market mechanism as the most effective way of delivering societal change.3 However, despite some 1 limited discussion of the potential impacts of this commercial engagement4 there has been no systematic investigation of the form, structures and impacts of commercial engagement in fair trade, and what this means for the future of the social movement. -

Fair Trade Activism Since the 1960S Van Dam, P

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Challenging Global Inequality in Streets and Supermarkets: Fair Trade Activism since the 1960s van Dam, P. DOI 10.1007/978-3-030-19163-4_11 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Histories of Global Inequality Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Dam, P. (2019). Challenging Global Inequality in Streets and Supermarkets: Fair Trade Activism since the 1960s. In C. O. Christiansen, & S. L. B. Jensen (Eds.), Histories of Global Inequality: New Perspectives (pp. 255-276). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978- 3-030-19163-4_11 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Challenging Global Inequality in Streets and Supermarkets: Fair Trade Activism since the 1960s Peter van Dam CHALLENGING GLOBAL INEQUALITY ON THE GROUND In 1967, the Dutch economist Harry de Lange noted that ‘[w]ithin a rela- tively short time-span, the question of the relation between poor and rich countries has become the pivotal issue in international economic politics and in the grand world politics themselves’.1 Nonetheless, the issue deserved more attention, he added. -

An Inspiration for Change

Annual Report 2007 An Inspiration for Change Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International An Inspiration for Change Message from Barbara Fiorito Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO) — Annual Report 2007 Chair of the Board of Directors FLO’s 2007 annual report comes at a pivotal 2007 Inspired by the groundbreaking achievements 2007 marked the tenth anniversary of FLO. The Representing networks in Africa, Asia and Latin moment in the life of the organization. This year we of our first decade, in 2007 FLO started a major incredible growth of Fairtrade over the last ten years America, they will help to shape the direction of celebrated ten years of momentous growth and strategic review involving all stakeholders to look has been achieved through the dedication and hard Fairtrade as equal partners. change, which included these landmark events: ahead at Fairtrade’s future. work of remarkable people. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the staff at the national During 2007 the newly expanded FLO Board 1997 FLO was established, bringing together all In this report we outline how Fairtrade works, Labelling Initiatives, FLO, partner organizations, agreed changes to standards that will see improved Fairtrade Labelling Initiatives under one umbrella our achievements in 2007 and our direction for the the wider fair trade movement and licensees. Their trading conditions and better prices for coffee and and introducing worldwide standards and future. belief in Fairtrade has secured a better future for tea growers. First, there will be an increase in the certification. millions of growers and their families. Their work price paid to coffee growers. -

The Fairtrade Foundation

MARKETING EXCELLENCE The Fairtrade Foundation Marketing for a better world headline sponsor Marketing Excellence | Foreword Foreword By Amanda Mackenzie What is marketing excellence? Marketing excellence can drive breakthrough business They have established this reputation over a period results for the short and long-term. Marketing of more than 28 years, and they have always been excellence requires great strategic thinking, great based on the principle of searching out the best creative thinking and perfect execution. examples of different marketing techniques in action, that showcase great strategic thinking, great But how do we assess marketing excellence? First we creativity and perfect execution. choose brilliant industry judges who are all experienced and successful practitioners of excellence and we In order to be a winner of one of the Society’s Amanda Mackenzie, ask them to pick out the cases which they see as Awards, marketers have to demonstrate that what President of The remarkable. We ask them to look for two key qualities they have done is outstanding in comparison with Marketing Society from our winners: creativity and effectiveness. marketing in all industries not just their own and Chief Marketing particular sector. & Communications But marketing continuously changes and evolves, as Officer at Aviva consumers become more sophisticated and demanding If a marketing story has been good enough to impress and the media for communicating with them ever more our judges, then all marketers can learn from it – diverse. So the standards for marketing excellence however senior they have become. The collection change and in turn become more demanding. of case histories brought together here is the best of the best from the past two years of our Awards, and We believe that The Marketing Society Awards for I am confident that it truly demonstrates marketing Excellence in association with Marketing set the excellence. -

Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement

SEED WORKING PAPER No. 30 Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement by Andy Redfern and Paul Snedker InFocus Programme on Boosting Employment through Small EnterprisE Development Job Creation and Enterprise Department International Labour Office · Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2002 First published 2002 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; e-mail: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; e-mail: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO Creating Market Opportunities for Small Enterprises: Experiences of the Fair Trade Movement Geneva, International Labour Office, 2002 ISBN 92-2-113453-9 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Fair Trade 1 Fair Trade

Fair trade 1 Fair trade For other uses, see Fair trade (disambiguation). Part of the Politics series on Progressivism Ideas • Idea of Progress • Scientific progress • Social progress • Economic development • Technological change • Linear history History • Enlightenment • Industrial revolution • Modernity • Politics portal • v • t [1] • e Fair trade is an organized social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries to make better trading conditions and promote sustainability. It advocates the payment of a higher price to exporters as well as higher social and environmental standards. It focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine,[2] fresh fruit, chocolate, flowers, and gold.[3] Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect that seek greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[4] There are several recognized Fairtrade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO/Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing