Research in Distance Education: 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instrumental Newsletter

EDITION #20 – September 2008 SPECIAL "SHADOZ" ISSUE!! "Shadoz 2008" marked our 6th anniversary, as well as the 50th anniversary of Cliff and The Shadows. Yet another new venue, and, from all reports the best yet. On a sad note, we recently lost one of our Shadoz friends, Don Hill. Don played drums for Harry's Webb and The Vikings last year, and was one of the 'stalwarts' of Shadoz in recent times. R.I.P. Don. TONY KIEK (Keyboards) and GEORGE LEWIS (Guitar) were fresh from a tour of the UK, where they appeared at a number of Shadows clubs. They were gracious enough to help out by filling the 'dreaded' opening spot. Their set was a wonderful introduction to the day, and they featured some great sounds with WONDERFUL LAND / FANDANGO (with WALTZING MATILDA intro) / DANCES WITH WOLVES / THING-ME-JIG / RODRIGO'S CONCERTO / GOING HOME (THEME FROM 'LOCAL HERO') / THE SAVAGE / SPRING IS NEARLY HERE Whilst Tony and George travelled down from Sydney, no less a feat were the next band, who have travelled from overseas – Phillip Island! - ROB WATSON (Bass) was formerly with Melbourne group "The Avengers", TONY MERCER (Lead Guitar) also played with various Melbourne groups before "retiring" to the island and forming "SHAZAM", MIKE McCABE (Rhythm) worked in England in the 60's with "Hardtack", MARTY SAUNDERS (Drums) played with the popular showband "Out To Lunch" amongst others, and JEFF CULLEN (Lead vocals and rhythm guitar) sang with The Aztecs in Sydney before Billy Thorpe, then with The Rat Finks. A nice mix of Shads and non-Shads numbers included ADVENTURES IN PARADISE / MAN OF MYSTERY / ATLANTIS / THE CRUEL SEA / THE RISE AND FALL OF FLINGEL BUNT / GENIE WITH THE LIGHT BROWN LAMP / IT'S A MAN'S WORLD / THE SAVAGE / CINCINNATTI FIREBALL (voc) / LOVE POTION NO.9 (voc) / THE WANDERER (voc) / THE STRANGER / WALK DON'T RUN One of the joys of "Shadoz" is the ability to welcome newcomers to our shindig. -

Cockburn Central Community Concert Feat. Ross Wilson

cockburn.wa.gov.au Media Release 27 January 2020 Experience a Cool World at Cockburn’s annual free community concert Now Listen! In the famous opening line of the iconic Daddy Cool track of the same name, Ross Wilson will have you listening, singing and dancing at this year’s free community concert in the City of Cockburn. Wilson, the ultimate Daddy Cool, will headline the Cockburn Central Community Concert on 8 February at 7pm. Teamed with the expert MCing talents of Australian actor/comedian Pete Rowsthorn aka Bretty from Kath and Kim, Wilson will be ably supported by popular WA classic rock tribute band the Wizards of Oz. Pack a yummy picnic and a soft blanket for the Fremantle Dockers official training ground at Victor Kailis Oval, Cockburn ARC, 31 Veterans Parade, Cockburn Central. There’s lots of parking, or walk from Cockburn Station if catching a connecting bus or train. Consider leaving the car at home and ride your bike instead. Bike racks are available at the entrance to Cockburn ARC, or carpool with family or friends, or use public transport available at Cockburn train station. Some food and drink vendors will be available but there will be no ATM facilities so bring cash for your purchases. Wilson’s Australian music success story began in Melbourne in 1964 but his efforts became widely known in 1970 with the unforgettable Daddy Cool. The band became the nation’s first to make an impact on the US touring scene in the Document Set ID: 9082320 Version: 1, Version Date: 12/02/2020 cockburn.wa.gov.au Media Release early 1970s, supporting acts including Fleetwood Mac, Deep Purple, Linda Ronstadt and Earth Wind & Fire. -

Children of the Revolution Music Credits

Original Music Nigel Westlake Music Co-ordinator Christine Woodruff Original Music Composed, Orchestrated & Produced by Nigel Westlake Orchestral Recording Engineer Christo Curtis Original Music Performed By The Victorian Philharmonic Orchestra Orchestra Leader Rudolph Osadnik Orchestral Manager Ron Layton Conducted By David Stanhope Original Music Recorded At ABC Southbank Studios, Melbourne Computer Scoring & Copying of Music Carl Vine Assitant (sic) to the Composer Jan Loquet Westlake MUSIC TRACKS Alexander Nevsky Cantata Written By Sergei Prokofiev © Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Performed by "Latvija" Chorus/Gewandhausorchester Leipzig Conducted by Kurt Masur Courtesy Teldec International By arrangement with Warner Music Australia Pty Ltd and Performed by Rundfunksolisten-Vereinigung Berlin/ Rundfunkchoir Berlin/RSB Conducted by Wolf-Dieter Hauschild Courtesy Berlin Classics/"Edel" Company Hamburg, Germany Lieutenant Kije Suite Written by Sergei Prokofiev © Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Performed by Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra Conducted by Loris Tjeknavorian Courtesy ASV Records Ltd and Performed by Czecho-Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra (Kosice) Conducted by Andrew Mogrelia Courtesy HNH International L'Internationale Written by Eugene Pottier/Pierre Degeyter © Le Chant Du Monde Performed by The Bolshoi Theatre Choir Courtesy of Melodiya under licence from BMG Australia Limited "The Ghost" from Hamlet Written by Dmitri Shostakovich © Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Performed by Belgian Radio Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Jose Serebrier Courtesy of RCA Victor Red Seal Under licence from BMG Australia Limited Le Chant Des Partisans Written by Atourov/Alimov/Alexandrov Performed by Red Army Choir Courtesy 7 Productions Planett Begin The Beguine Written by Cole Porter © Harms Inc Performed by The Paul Grabowsky Orchestra When Your Lover Has Gone Written by E. -

Retro-80S-Hits.Pdf

This document will assist you with the right choices of music for your retro event; it contains examples of songs used during an 80’s party. Song Artist Greece 2000 18 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You 1927 I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing ( If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls Take On Me A Ha Poison Arrow ABC The Look Of Love ABC When Smokey Sings ABC Who Made Who AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Stand & Deliver Adam & The? Ant Music Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Classic Adrian Gurvitz Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Manhattan Skyline A-Ha Take On Me A-Ha Love Is Alannah Myles Poison Alice Cooper Love Resurrection Alison Moyet Don't Talk To Me About Love Altered Images Take It Easy Andy Taylor Japanese Boy Aneka Obession Animotion Election Day Arcadia Sugar Sugar Archies 0402 277 208 | [email protected] | www.djdiggler.com.au | 21 Higgs Ct, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia 4178 Downhearted Australian Crawl Errol Australian Crawl Reckless Australian Crawl Shutdown Australian Crawl Things Don't Seem Australian Crawl Love Shack B52's Roam B52's Strobelight B52's Tarzan Boy Baltimora I Want You Back Bananarama Venus Bananarama Heaven Is A Place On Earth Belinda Carlisle Mad About You Belinda Carlisle Imagination Belouis Some Sex I'm A Berlin Take My Breath Away Berlin Key Largo Bertie Higgins In A Big Country Big Country Look Away Big Country Hungry Town Big Pig Lovely Day Bill Withers Dancing With Myself Billy Idol Flesh For Fantasy Billy Idol Hot In The City Billy Idol Rebel Yell Billy -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

Acts • Port Fairy Folk MUSIC Festival – 1977 to 2016

International Boys of the Lough (Scotland) Acts • Port Fairy Folk MUSIC National Abominable Snow Band, Acacia Trio, Boys of The Lough, Barefoot Nellie, John Beavis, Festival – 1977 to 2016 Ted Egan , Captain Moonlight, Bernard Carney, There are around 3500 acts that have been Elizabeth Cohen, Christy Cooney, Alfirio Cristaldo, booked, programmed and played at Port Fairy John Crowl, Dave Diprose, Five N' A Zak, Fruitcake since 1977. of Australian Stories, Stan Gottschalk, Rose No-one has actually counted all of them. Many Harvey, Greg Hastings, High Time String Band, Street Performers and workshop acts have not Richard Keame, Jindivick, Stephen Jones, been listed here. Sebastian Jorgensen, Tony Kishawi, Jamie Lawrence, Di McNicol, Malarkey, Muddy Creek December 2 - 4th 1977 Bush Band, The New Dancehall Racketeers, Tom Declan Affley, Tipplers All, Poteen, Nick Mercer, Nicholson, Trevor Pickles, Shades of Troopers Bush Turkey, Flying Pieman and many more Creek, Gary Shields, Judy Small, Danny Spooner, Shenanigans, Sirocco, Tara, Mike O'Rourke, Tam O December 1- 3rd 1978 Shanter, Tim O' Brien, Ian Paulin, Pibroch, Shirley Declan Affley, Buckley's Bush Band, John Power, Cathy O'Sullivan and Cleis Pearce, Poteen, MacAuslan, Poteen, Rum Buggery and The Lash Tansey's Fancy, Rick E Vengeance, Lisa Young Trio, Kel Watkins, Tim Whelan, Fay White, Stephen December 7 -9th 1979 Whiteside, Witchwood, Geoff Woof, Yabbies Redgum, Finnegans Wake, Poteen, Mick and Helen Flanagan, Tim O'Brien and Captain Moonlight, March 8 - 11th 1985 Buckley's Bush Band, -

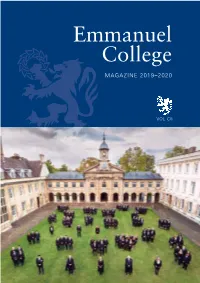

View 2020 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOL CII MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2019–2020 VOLUME CII II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2019–2020 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2021. Enquiries, news about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or submitted via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/keepintouch/. General correspondence about the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP is the person to contact about obituaries. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, and especially to Carey Pleasance for assistance with obituaries and to Amanda Goode, the college archivist, whose knowledge and energy make an outstanding contribution. Back issues The college holds an extensive stock of back numbers of the Magazine. Requests for copies of these should be addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. -

Ten Best Australian Songs

MEDIA RELEASE Embargoed until 28 May 2001 at 11.00pm THE FINAL LIST: APRA’S TEN BEST AUSTRALIAN SONGS “Friday on My Mind” has been on the minds of Australians since 1967, earning itself the number one position on APRA’s list of Ten Best Australian Songs. The Harry Vanda/George Young composition was honoured at the 2001 APRA Music Awards in Sydney tonight, with an electrifying performance of the song by You Am I featuring special guest guitarist, Harry Vanda himself. After weeks of speculation, APRA revealed the ten best and most significant Australian songs of the past 75 years at tonight’s Awards ceremony, which featured an extraordinary, poignant and sometimes humorous retrospective of classic Australian music. Voted by 100 distinguished Australian writers, musicians, critics and broadcasters, the complete APRA Top 30 list was compiled to celebrate APRA’s 75th anniversary, and to honour the songwriters who have provided the soundtrack for generations of Australians. While numbers 11-30 were announced earlier this month, APRA saved details of the big ten until tonight’s celebrations. Originally immortalised by Vanda and Young’s 1960s group The Easybeats, “Friday on My Mind” was subsequently covered by David Bowie. Tonight’s rocking version capped off APRA’s biggest Awards night ever. Ross Wilson was on hand to sing the number 2 song, “Eagle Rock,” which he penned for his group Daddy Cool and made a hit in 1971. A video tribute to the number 3 song, Midnight Oil’s classic “Beds Are Burning,” was introduced by Senator Aden Ridgeway, Australian Democrats Deputy Parliamentary Leader and spokesperson for Reconciliation. -

World Coming to OZ Stead Capturing the Rough'n'ready, Street -Level Rawness of Oz 10Ak1 Rock

4t34204:erotlik §';°s Ydr t& 'Me tyúT $'. W fgrf Rules The Waves UA3.$i:,i,..-.... 4k, Continued from page TIA -58 tie 49 WAVZ A Billboard Daddy Cool, Spectrum, Ariel and the Loved Ones. In fact we hAAif= did a version of a big hit by the Loved Ones as a single. We did SPOTLIGHT it just at the right time, when Australians were getting behind ?;f.41:4 ON their own musical heritage and realizing how strong and good THE our own music actually is. "The best of all about being an Australian band is that we no longer have to leave the country that we are most creative ti:: LIVE in and go overseas. Now we can stay here and the world is coming to us." Just why the world is coming to Australia's door after years E N of kamikaze missions and lemming rushes to the other side of A ii14..ew: l . the world, has no convenient answer HUNTERS & COLLECTORS -Tribal funk that, despite no U.S. but the bottom line O F - seems to be the power, the rawness, the edge that character- : e record deal, has picked up airplay in North America. izes the music £t.S -the almighty 'pub boogies.' G.ìr M. When film producer David Elfick made the rock musical iigiilii "Starstruck," he approached it with the aim of moving away .x/oft from a "Grease /Can't Stop the Music" type slickness and in- MiN i4i AUSTRAIIA_Itzet:,...7., World Coming To OZ stead capturing the rough'n'ready, street -level rawness of Oz 10ak1 rock. -

Bibliography: Books 1992-2012

Museum Studies, Museology, Museography, Museum Architecture, Exhibition Design Bibliography: Books 1992-2012 Luca Basso Peressut (ed.) Updated January 2012 2 Sections: p. 3 Introduction p. 4 General Readers, Anthologies, and Dictionaries p. 18 The Idea of Museum: Historical Perspectives p. 38 Museums Today: Debate and Studies on Major Issues p. 97 Making History and Memory in Museums p. 103 Museums: National, Transnational, and Global Perspectives p. 116 Representing Cultures in Museums: From Colonial to Postcolonial p. 124 Museums and Communities p. 131 Museums, Heritage, and Territory p. 144 Museums: Identity, Difference and Social Equality p. 150 ‘Hot’ and Difficult Topics and Histories in Museums p. 162 Collections, Objects, Material Culture p. 179 Museum and Publics: Interpretation, Learning, Education p. 201 Museums in a digital age: ICT, virtuality, new media p. 211 Museography, Exhibitions: Cultural Debate and Design p. 247 Museum Architecture: Theory and Practice p. 266 Contemporary Art, Artists and Museums: Investigations, Theories, Actions p. 279 Museums and Libraries Partnership Updated January 2012 3 Introduction This bibliography is intended as a general overview of the printed books on museums topics published in English, French, German, Spanish and Italian in Europe and the United States over the last twenty years or so. The chosen period (1992-2012) is only apparently arbitrary, since this is the period of major output of studies and research in the rapidly changing contemporary museum field. The 80s of the last century began with the affirmation of the schools of ‘museum studies’ in the Anglophone countries, as well as with the development of the Nouvelle Muséologie in France (consolidated in 1985 with the foundation of the Mouvement International pour la Nouvelle Muséologie-MINOM, as an ICOM affiliate). -

Oz Musical Music Credits

Music Produced & Arranged by Ross Wilson MUSIC Living in the Land of Oz Greaseball The Mood Who's Gonna Love You Tonight Ross Wilson (Ross Wilson) You're Driving Me Insane Graham Matters (Baden Hutchins) Our Warm Tender Love Joy Dunstan (Gary Young) Beatin' Around The Bush Glad I'm Living Here Jo Jo Zep (Wayne Burt) Music Engineer John French NB: for the American release, as well as retitling the film 20th Century Oz, the distributors placed a new version of the Ross Wilson song "Living In The Land Of Oz" over the opening credits, recorded by Hero, an act signed to Interplanetary Records. The American opening credit sequence can be seen in the region four DVD release extras. To an Australian ear used to the original, the track is terrible, completely out of sympathy with the intent of the film to celebrate Australian pop music. Ross Wilson was in the 1970s the incarnation of Australian pop music, through his band Daddy Cool, and through producing Skyhooks. His career in Mondo Rock and as a solo artist was less successful, but still comparatively strong. As a result, his career is covered in an extensive wiki here, and at time of writing (May 2013) he still had an active website here. There's also a Daddy Cool page here, and for early Ross Wilson, in Sons of the Vegetal Mother, Melbourne 1969-71 (who turn up in the extras of the DVD release), see Milesago, here. Living in the Land of Oz was Wilson's first solo single after he had waited out his contact with Wizard Records; he did it for his own label Oz Records. -

Official Guide March 2020 #Lovebright #Brighterdaysfestival Brighter Days Foundation Committee

6-8 OFFICIAL GUIDE MARCH 2020 #LOVEBRIGHT #BRIGHTERDAYSFESTIVAL WWW.BRIGHTERDAYS.ORG.AU BRIGHTER DAYS FOUNDATION COMMITTEE President Paul Terrill Vice President Jason Reid Secretary Jim Henwood Tresurer Matt Powell Members Bright Committee Steve Dundon Mick Abbate Greg Bergin Brian Taggart Sue Binion Gary Murray Glenn Chesser Glenn Jordan The Brighter Days Foundation Incorporated Michelle Dundon Jodie Germaine is a registered charity and is endorsed as a Ross Finlayson Geoff Costa Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) Julie Minarelli Glen Hough Any donation over $2 is tax deductible. John Nixon Craig Sholl Kelly Pyers Cathie Reid Kirsty Reid Wes Reid James Theuma Sue Theuma Billy Bergin John Coen Facebook: Instagram: brighterdays @brighterdaysfestival 2 WELCOME BRIGHTER DAYS 2020 Hello everyone and welcome to the 2020 Brighter Days Festival. We’re excited to be hosting the festival this year at this fantastic new space at Pioneer Park. We want to say a massive thanks to all those who have been working tirelessly behind the scenes to prepare the site, in particular our local Brighter Days committee members, friends of Brighter Days and the Alpine Shire Council. This new site gives our festival longevity by allowing us to safely host the growing number of people coming along each year which means we can continue to support the important work of our charities; Debra Australia, The Cooper Trewin Foundation [SUDC] and EB Research. I am incredibly proud the Brighter Days Foundation has been able to donate more $1.6 million to these charities since we began seven years ago. The ongoing and generous support of the Brighter Days community has enabled these organisations to continue their important work including clinical trials, research and on the ground support to families in need.