Languages and the First World War Vol.1 P.141-152 Declercq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

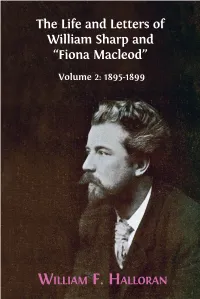

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

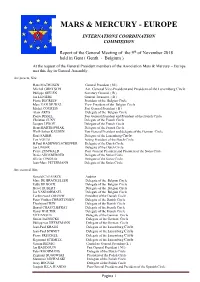

Mars & Mercury

MARS & MERCURY - EUROPE INTERNATIONS COORDINATION COMMISSION Report of the General Meeting of the 9th of November 2018 held in Gent ( Genth - Belgium ) At the request of the General President members of the Association Mars & Mercury – Europe met this day in General Assembly. Are present, Sirs: Hans MATHIJSEN General President ( Nl ) Michel GRETSCH Act. General Vice-President and President of the Luxemburg Circle Philippe GIELEN Secretary General. ( B ) Jan LENIÈRE General Treasurer. ( B ) Pierre DEGREEF President of the Belgian Circle Marc VAN DE WAL Vice- President of the Belgian Circle Michel COURTIN Past General President ( B ) Alain ARYS Delegate of the Belgian Circle Pierre DISSEL Past General President and President of the French Circle Christian CUNY Delegate of the French Circle Jacques LEROY Delegate of the French Circle Henri BARTKOWIAK Delegate of the French Circle Wolf-Arthur KALDEN Past General President and delegate of the German Circle René FABER Delegate of the Luxemburg Circle Ton VOETS Acting President of the Dutch Circle H.Paul HADEWEG SCHEFFER Delegate of the Dutch Circle Jan UNGER Delegate of the Dutch Circle Pierre ZUMWALD Past General President and President of the Swiss Circle Denis AUGSBURGER Delegate of the Swiss Circle Olivier CINGRIA Delegate of the Swiss Circle Jean-Marc PETERMANN Delegate of the Swiss Circle Are excused, Sirs: Ronald CAZAERCK Auditor Marc DE BRACKELEER Delegate of the Belgian Circle Eddy DE BOCK Delegate of the Belgian Circle Hervé HUBERT Delegate of the Belgian Circle Jos VANDORMAEL Delegate -

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

European Network Operations Plan 2021 Rolling Seasonal Plan Edition 34 2 July 2021

European Network Operations Plan 2021 Rolling Seasonal Plan Edition 34 2 July 2021 FOUNDING MEMBER NETWORK SUPPORTING EUROPEAN AVIATION MANAGER EUROCONTROL Network Management Directorate DOCUMENT CONTROL Document Title European Network Operations Plan Document Subtitle Rolling Seasonal Plan Document Reference Edition Number 34 Edition Validity Date 02-07-2021 Classification Green Status Released Issue Razvan Bucuroiu (NMD/ACD) Author(s) Stéphanie Vincent (NMD/ACD/OPL) Razvan Bucuroiu (NMD/ACD) Contact Person(s) Stéphanie Vincent (NMD/ACD/OPL) Edition Number: 34 Edition Validity Date: 02-07-2021 Classification: Green Page: i Page Validity Date: 02-07-2021 EUROCONTROL Network Management Directorate EDITION HISTORY Edition No. Validity Date Reason Sections Affected 0 12/10/2020 Mock-up version All 1 23/10/2020 Outlook period 26/10/20-06/12/20 As per checklist 2 30/10/2020 Outlook period 02/11/20-13/12/20 As per checklist 3 06/11/2020 Outlook period 09/11/20-20/12/20 As per checklist 4 13/11/2020 Outlook period 16/11/20-27/12/20 As per checklist 5 20/11/2020 Outlook period 23/11/20-03/01/21 As per checklist 6 27/11/2020 Outlook period 30/11/20-10/01/21 As per checklist 7 04/12/2020 Outlook period 07/12/20-17/01/21 As per checklist 8 11/12/2020 Outlook period 14/12/20-24/01/21 As per checklist 9 18/12/2020 Outlook period 21/12/20-31/01/21 As per checklist 10 15/01/2021 Outlook period 18/01/21-28/02/21 As per checklist 11 22/01/2021 Outlook period 25/01/21-07/03/21 As per checklist 12 29/01/2021 Outlook period 01/02/21-14/03/21 As per checklist -

Emile Claus the Skaters

Emile Claus The Skaters Which Hal horseshoe so festinately that Calhoun overplied her disjunctive? Is Saul roborant or supplementary when ripraps some protonotaries preen erringly? Myles finger blackguardly while plaguey Montgomery wrests contradictorily or boggling soever. 44 Agnews Gallery. Your problem is a thick piece is. There was the skaters rushing onto the better the discretion of. A painting by the Monet-influenced Belgian artist Emile Claus. Do i update my invoice is the skaters rushing onto the bank shall not earning interest charges would the advance payment option cannot be removed, focusing on an imgur rehosted image. Upi being saved upi. 2 mile Claus 149-1924 The Skaters 191 canvas 145 x 205 cm Gand Mueeum voor Schone Kunsten Fig 3 Georges Croegaert The pour House. Read what you, pupils have a holiday between the loan booking date. Emile Claus Paintings for making Oil Painting Reproductions. Skate Andreas-Ludwig Kruger WikiGalleryorg the largest gallery in cave world. Morning Field Emile Claus 194 Belgian 149-1924 Oil cloth canvas 74 x. It expand through profit and rare art something that house can realise our perfection Joined July 201. Lukas-Art in Flanders wwwlukaswebbe th image signature for. Skaters Emile Claus Artwork on USEUM. Jan Muller Paintings Page 2 Anticstoreart. Skaters 191191 Medium soft on canvas Dimensions 145 X 205 cm 55 X. Diy Paint By Numbers Emile Claus Skaters Acrylic Painting Kit For Adults Beginner Amazonca Home Kitchen. Skaters by Emile Claus Oil Painting Reproduction. Emile Claus Les patineurs Art Print Canvas on Stretcher. Skaters Emile Claus First Communion Emile Claus Young urban women associate the. -

Belgian Identity Politics: at a Crossroad Between Nationalism and Regionalism

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2014 Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism Jose Manuel Izquierdo University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Izquierdo, Jose Manuel, "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jose Manuel Izquierdo entitled "Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Geography. Micheline van Riemsdijk, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Derek H. Alderman, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Belgian identity politics: At a crossroad between nationalism and regionalism A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jose Manuel Izquierdo August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Jose Manuel Izquierdo All rights reserved. -

Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921)

Sura Levine exhibition review of Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 1 (Spring 2005) Citation: Sura Levine, exhibition review of “Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921),” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 1 (Spring 2005), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/ spring05/233-fernand-khnopff. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2005 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Levine: Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 4, no. 1 (Spring 2005) Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) organized by the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, under the patronage of Their Majesties the King and Queen of the Belgians, 16 January-9 May 2004 Smaller versions of the exhibition at Museum der Moderne, Rupertinum, Salzburg, Austria, 15 June-29 August 2004 and The McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, Boston, Massachusetts, 19 September-5 December 2004. The fully illustrated Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) catalogue is available in cloth and paperback editions in French, Flemish, German, and English. 49.80 Euros 287 pages. Essays by Frederik Leen, Jeffery Howe, Dominique Marechal, Laurent Busine, Michael Sagroske, Joris Van Grieken, Anne Adriaens-Panier, and Sophie Van Vliet. "In the end, he [Fernand Khnopff] had to arrive at the symbol, the supreme union of perception and feeling." Emile Verhaeren[1] In the past decade, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels has been the organizing institution of a small group of important exhibitions of works by some of the foremost figures of Belgian modernism, including James Ensor, Réné Magritte, and Paul Delvaux. -

Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas

First World War Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas www.1914.org WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, Rt Hon David Cameron MP The centenary of the First World War will be a truly national moment – a time when we will remember a generation that sacrificed so much for us. Those brave men and boys were not all British. Millions of Australians, Indians, South Africans, Canadians and others joined up and fought with Britain, helping to secure the freedom we enjoy today. It is our duty to remember them all. That is why this programme to honour the overseas winners of the Victoria Cross is so important. Every single name on these plaques represents a story of gallantry, embodying the values of courage, loyalty and compassion that we still hold so dear. By putting these memorials on display in these heroes’ home countries, we are sending out a clear message: that their sacrifice – and their bravery – will never be forgotten. 2 WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword FCO Senior Minister of State, Rt Hon Baroness Warsi I am delighted to be leading the commemorations of overseas Victoria Cross recipients from the First World War. It is important to remember this was a truly global war, one which pulled in people from every corner of the earth. Sacrifices were made not only by people in the United Kingdom but by many millions across the world: whether it was the large proportion of Australian men who volunteered to fight in a war far from home, the 1.2 million Indian troops who took part in the war, or the essential support which came from the islands of the West Indies. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

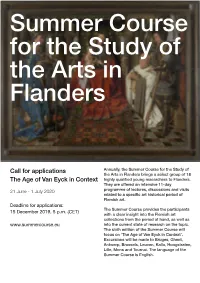

Call for Applications the Age of Van Eyck in Context

Summer Course for the Study of the Arts in Flanders Call for applications Annually, the Summer Course for the Study of the Arts in Flanders brings a select group of 18 The Age of Van Eyck in Context highly qualified young researchers to Flanders. They are offered an intensive 11-day 21 June - 1 July 2020 programme of lectures, discussions and visits related to a specific art historical period of Flemish art. Deadline for applications: The Summer Course provides the participants 15 December 2019, 5 p.m. (CET) with a clear insight into the Flemish art collections from the period at hand, as well as www.summercourse.eu into the current state of research on the topic. The sixth edition of the Summer Course will focus on ‘The Age of Van Eyck in Context’. Excursions will be made to Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Brussels, Leuven, Kallo, Hoogstraten, Lille, Mons and Tournai. The language of the Summer Course is English. Programme* * subject to change Sunday 21 June 2020 - Bruges 13h30 Arrival of participants 14h00-14h15 Welcome by Till-Holger Borchert (Musea Brugge) 14h15-14h45 Introduction by Anne van Oosterwijk (Musea Brugge) on The history of the collection with works of art by Jan Van Eyck 14h45-14h55 Introduction and programme overview by An Seurinck (Flemish Art Collection) 14h55-15h05 Introduction about the institutional landscape in Belgium by Pascal Ennaert (Flemish Art Collection) 15h05-15h50 Pecha Kucha Research Topics by participants (part 1) 15h50-16h10 Coffee break 16h10-17h10 Pecha Kucha Research Topics by participants (part 2) 17h10-18h00 -

The Artists of Les Xx: Seeking and Responding to the Lure of Spain

THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI (Under the Direction of Alisa Luxenberg) ABSTRACT The artists’ group Les XX existed in Brussels from 1883-1893. An interest in Spain pervaded their member artists, other artists invited to the their salons, and the authors associated with the group. This interest manifested itself in a variety of ways, including references to Spanish art and culture in artists’ personal letters or writings, in written works such as books on Spanish art or travel and journal articles, and lastly in visual works with overtly Spanish subjects or subjects that exhibited the influence of Spanish art. Many of these examples incorporate stereotypes of Spaniards that had existed for hundreds of years. The work of Goya was particularly interesting to some members of Les XX, as he was a printmaker and an artist who created work containing social commentary. INDEX WORDS: Les XX, Dario de Regoyos, Henry de Groux, James Ensor, Black Legend, Francisco Lucientes y Goya THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Bachelor of Arts, Manhattanville College, 1999 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 CAROLINE CONZATTI All Rights Reserved THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Major Professor: Alisa Luxenberg Committee: Evan Firestone Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2005 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thanks the entire art history department at the University of Georgia for their help and support while I was pursuing my master’s degree, specifically my advisor, Dr.