A Case for Dialogical Memorialisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kittanning Medal Given by the Corporation of Tlie City of Philadelphia

Kittanning Medal given by the Corporation of tlie City of Philadelphia. Washington Peace Medal presented to Historical Society of Pennsylvania March 18, 188i> by Charles C. CresBon. He bought two (this a'nd the Greeneville Treaty medal) for $30.00 from Samuel Worthington on Sept 2!>. 1877. Medal belonged to Tarhee (meaning The Crane), a Wyandot Chief. Greeneville Treaty Medal. The Order of Military Merit or Decoration of the Purple Heart. Pounded Try General Washington. Gorget, made by Joseph Richardson, Jr., the Philadelphia silversmith. THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY. VOL. LI. 1927. No. 2. INDIAN AND MILITARY MEDALS FROM COLONIAL TIMES TO DATE BY HARROLD E. GILLINGHAM.* "What is a ribbon worth to a soldier? Everything! Glory is priceless!" Sir E. B. Lytton, Bart. The nature of man is to demand preferences and distinction. It is uncertain who first instituted the custom of granting medals to individuals for acts of bravery or for military services. Scipio Aemilius is said to have bestowed wreaths of roses upon his men of the eleventh Legion at Carthage in 146 B. C., and the Chinese are reported to have issued awards during the Han Dynasty in the year 10 A. D., though no de- scription thereof is given. Tancred says there used to be in the National Coin Collection of France, a gold medal of the Roman Emperor Tetricus, with loops at- tached, which made it appear as if it was an ornament to wear. Perhaps the Donum Militare, and bestowed for distinguished services. We do know that Queen Elizabeth granted a jewelled star and badge to Sir Francis Drake after his famous globe encircling voy- age (1577-1579), and Tancred says these precious relics were at the Drake family homestead, "Nutwell * Address delivered before the Society, January 10, 1927 and at the meeting of The Numismatic and Antiquarian Society February 15, 1926. -

Skinners: Patriot "Friends" Or Loyalist Foes? by Lincoln Diamant

Skinners: Patriot "Friends" or Loyalist Foes? by Lincoln Diamant t is never too late to correct a libel, even though, as Mark Twain joked, a lie is halfway around the world before the truth can pull on its pants. But to set the record straight for future lower I Hudson Valley histories, pamphlets, and schoolbooks . the answer to the title question of this essay is, simply, "loyalist foes." For more than a century and a half, the patriot irregulars who fought British and German invaders in the "neutral ground" between royalists and patriots in Westchester County during the Revolu tionary War have been slandered. Ignoring printed evidence 165 years old, too many authors and eminent historians have accused these patriotic citizens of war crimes equal to or worse than those committed by the British Army, its loyalist allies, and its German mercenaries. Unfortunately, the libel continues, telling us more about the ways mistakes are repeated in contemporary historical scholarship than we may wish to acknowledge. Correcting an error so long enshrined in the literature is no easy task. Where to begin? Perhaps the best place is Merriam-Webster's Una bridged Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, which carries this definition: "Skinner: one of a band of guerrillas and irregular cavalry claiming attachment to either the British or American troops and operating in Westchester County in New York during the American Revolution.'" 50 The Hudson Valley Regional Review , September 1987, Volume 4, Number 2 "British or American?" Even the simplest definition is ambiguous, and it ignores an important piece of evidence about the origin of the name. -

Toledo Mud Hens 2017 Scout Sleepovers

Chartered by the Murbach-Siefert American Legion Post 479 in Swanton, OH August 2017 Pictures of activities, forms, updated news at our website www.swantonscouts.org August 19th is the Swanton The "Fall" Program will be starting up again soon! Meetings CORNFEST !! will be at the Scoutmaster's home so we can keep working "Rivals in the Corn" Who Ya Rootin' For? on Scout skills (T-2-1). Check the Website for the A PARADE to start the day off with at 10:30 calendar/schedule in case there are any changes, but the We will be participating in the parade first meeting is August 1st at 7pm. Put it down on your calendars and plan to join us! October 13th thru 15th District Fall Camporee October 1st & 2nd We'll be going back to the Operating Engineers in Cygnet. Swan Creek District Cub Family Camp Scouts can try their hand at a skid steer, crane or even a Check in is from noon to 2pm with flags at 2 and the backhoe! More details when they are available. stations start right after until 6pm and then dinner. This will be held @ Camp Miakonda again this year we'll post the flyer and details as soon as we get them Our "annual" Join Scouting Night will be September 13th Coming in September…. We'll meet at the Legion Hall at 6:00pm (Rain or Shine) to Popcorn Take Order Sales begin introduce Scouting to other young men and their families. popcorn sales end in November If you can, please come out and let the young men know popcorn will be distributed afterwards how much fun they can have in Scouting with us! We'll make sure everyone gets updated as fast as our Popcorn "Kernal" gets the marching orders for this year. -

Lafayette for Young Americans

Conditions and Terms of Use Copyright © Heritage History 2010 Some rights reserved This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, PUBLISHER'S NOTE however, are the property of Heritage History and are subject to certain restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the Much of the material in this book has already appeared integrity of the work, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure in Lafayette, We Come. This new volume omits the part that that compromised versions of the work are not widely disseminated. dealt with the War of 1914-1918, and adds new chapters In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this text, a dealing with Lafayette's adventures in the United States from copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date are the arrival of the French fleet under Rochambeau to the included at the foot of every page of text. We require all electronic and printed versions of this text include these markings and that users adhere to surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. the following restrictions. 1. You may reproduce this text for personal or educational purposes as long as the copyright and Heritage History version are included. -

Traveling Along the 1825/1828 D&H

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, Editor in Chief, Hudson Valley Magazine Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Art Director Richard Deon Business Manager Jean DeFino The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice a year by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. Thomas S. Wermuth, Director James M. Johnson, Executive Director Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair Maureen Kangas Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Barnabas McHenry J. Patrick Dugan Alex Reese Patrick Garvey Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2005 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Post: The Hudson River Valley Review c/o Hudson River Valley Institute Marist College 3399 North Road Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Tel: 845-575-3052 Fax: 845-575-3176 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.net Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). A one-year institutional subscription is $30. Subscribers are urged to inform us promptly of a change of address. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College, 3399 North Road, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 The Hudson River Valley Review was founded and published by Bard College, 1984-2002. Founding Editors, David C. Pierce and Richard C. Wiles The Hudson River Valley Review is underwritten by the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. ii From the Editors The historical net in this issue of The Hudson River Valley Review has been cast especially wide, spanning from the early eighteenth century right up to the twenty-first. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 September

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 September Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Third Friday of Sep – National POW/MIA day to pay tribute to the lives and contributions of the more than 83,000 Americans who are still listed as Prisoners of War or Missing in Action. Sep 16 1776 – American Revolution: The Battle of Harlem Heights restores American confidence » General George Washington arrives at Harlem Heights, on the northern end of Manhattan, and takes command of a group of retreating Continental troops. The day before, 4,000 British soldiers had landed at Kip’s Bay in Manhattan (near present-day 34th Street) and taken control of the island, driving the Continentals north, where they appeared to be in disarray prior to Washington’s arrival. Casualties and losses: US 130 | GB 92~390. Sep 16 1779 – American Revolution: The 32 day Franco-American Siege of Savannah begins. Casualties and losses: US/FR 948 | GB 155. Sep 16 1810 – Mexico: Mexican War of Independence begins » Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest, launches the Mexican War of Independence with the issuing of his Grito de Dolores, or “Cry of Dolores,” The revolutionary tract, so-named because it was publicly read by Hidalgo in the town of Dolores, called for the end of 300 years of Spanish rule in Mexico, redistribution of land, and racial equality. Thousands of Indians and mestizos flocked to Hidalgo’s banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and soon the peasant army was on the march to Mexico City. -

TOWN of BROOMK. '39 Mr

TOWN OF BROOM K. '33 harie was built while he was in the Board of was changed to Broome, in honor of the then Supervisors, and we simply write the truth when acting Lieutenant Governor, John Broome, who we say that but for the position taken by him was repeatedly elected with Daniel I). Tomp- and one or two of his associates, instead of the kins, as Governor. Undoubtedly, had not fine structure we now see, there would have death closed his successful and honored career been something decidedly inferior. in 1811, he would have retained the position Mr. Couchman is a farmer, and makes his to the close of Governor Tompkins admin- business as such a sort of profession. A large istration, at least, in 1816, as he was so highly part of his time at home is devoted to his admired by the people. library and the news of the day. His probity, The Catskill creek takes its rise in this town, and was fed a called ability, and geniality, have secured to him the formerly by large swamp, the confidence and esteem of the people of his dis- vlaie, (now pronounced rfy,) now drained, which has been a marked since the trict in a marked degree. Quickness of discern- locality ment, readiness of action and undoubted in- Aborigines of the country formed a path lead- from the Hudson near to tegrity are among his most decided character- ing River, Catskill, istics. He has been a Democratic wheel-horse the Schoharie valley and the wigwams of the western tribes of the confederation. -

John Paulding Commemorative Essay by Claire Royston

John Paulding Commemorative Essay by Claire Royston, Sleepy Hollow Sleepy Hollow High School, May 23, 2012 Claire Royston is a sophomore at Sleepy Hollow High School. She is 15 years old and lives in Sleepy Hollow with her parents and her two older brothers. Claire has been involved with music and the arts for her entire life and wants to continue with them. Claire thanks her family and friends for supporting her in everything she does and for always being there and she is very honored to have been given the opportunity to write about her home town. John Paulding 1758-1818 John Paulding was born on October 16, 1758. He is extremely deserving of a place in the Tarrytown-Sleepy Hollow Hall of Fame due to his brave actions and accomplishments during the Revolutionary War. Paulding, along with two other soldiers found and captured Major Andre, a spy for Benedict Arnold, near what is now known as Patriots Park in Tarrytown. His bravery helped foil Arnold’s plan and greatly helped America. He died in 1818 and a school was named after him on the hill above where the capture took place. Commemorative Essay by Claire Royston, Sleepy Hollow Sleepy Hollow High School, May 23, 2012 John Paulding Many people have lived or passed by the small villages of Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow. There have been many great men and women who made differences in these two towns and history has been made time and time again. The towns have prospered with the contributions of many important people, from great mayors and leaders, to small business owners and soldiers. -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. BG (Ret) Lance Betros, Dean of Academics, U.S. Army War College Executive Director Kim Bridgford, Professor of English, James M. Johnson, West Chester University Poetry Center The Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Chair in and Conference Hudson River Valley History Michael Groth, Professor of History, Wells College Research Assistants A lex Gobright Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, Marygrace Navarra State University of New York at New Paltz Hudson River Valley Institute COL Matthew Moten, Professor and Head, Advisory Board Department of History, U.S. Military Alex Reese, Chair Academy at West Point Barnabas McHenry, Vice Chair Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- Peter Bienstock Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Margaret R. Brinckerhoff Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Fordham University Frank J. Doherty BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English Emeritus, Shirley M. Handel Vassar College Maureen Kangas Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Mary Etta Schneider Marist College Gayle Jane Tallardy David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Robert E. Tompkins Sr. -

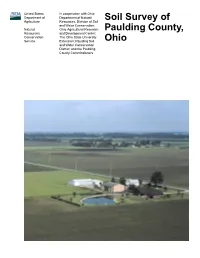

Soil Survey of Paulding County, Ohio

United States In cooperation with Ohio Department of Department of Natural Agriculture Resources, Division of Soil Soil Survey of and Water Conservation; Natural Ohio Agricultural Research Paulding County, Resources and Development Center; Conservation The Ohio State University Service Extension; Paulding Soil Ohio and Water Conservation District; and the Paulding County Commissioners 3 How To Use This Soil Survey General Soil Map The general soil map, which is a color map, shows the survey area divided into groups of associated soils called general soil map units. This map is useful in planning the use and management of large areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the map, identify the name of the map unit in the area on the color-coded map legend, then refer to the section General Soil Map Units for a general description of the soils in your area. Detailed Soil Maps The detailed soil maps can be useful in planning the use and management of small areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the Index to Map Sheets. Note the number of the map sheet and turn to that sheet. Locate your area of interest on the map sheet. Note the map unit symbols that are in that area. Turn to the Contents, which lists the map units by symbol and name and shows the page where each map unit is described. The Contents shows which table has data on a specific land use for each detailed soil map unit. Also see the Contents for sections of this publication that may address your specific needs. -

THE "Andre. CAPTURE" MEDAL

THE "ANDRe. CAPTURE" MEDAL ............................... Col. John T. Moorhead~ AUS - Ret’d OMSA # 1953 PREFACE: The photograph of the "Andr~ Capture" Medal sho,~n overleaf is that of an exact facsimile of a copy of one of the originals which were made by a silversmith, and are not properly medals, being made by a process known as "Repousse" which involves hammering on the reverse sides of two parts, which were then fastened together. The facsimiles were no doubt made from a mold of one of the original awards or a copy of an original ..... A display of this award had been designed for public exhibition and for photographing, by Colonel John T. Moorhead, member of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, No. 103732, whose great grandfather, Captain Thomas Houghtaling, sirved with the llth Regiment of the New York State Mounted Militia. Captain Houghtaling~ was born on November 14, 1731, and died on February 21, 1824. On September 23, 1780, three New York militiamen captured Major Andre/ of the British Army, and refusing his large offers of money, 4elivered him up to the American commanding officer of the district. Thus the treasonable intentions of General Arnold to surrender West Point to the enemy were frustrated. For this great service to their country they each received the thanks of Congress and a silver medal. The three militiamen so honored were: JOHN PAULDING, born in New York in 1759; and died in Wes~chester County, New York, February 18, 1848. DAVID WILLIAMS, born in Tarrytown, October 21, 1754, and died in Broome, Schoharie County, New York, August 2, 1831. -

RW250 Working with You to Bring Revolutionary War Era Activities Across Westchester County

RW250 Working with you to bring Revolutionary War era activities across Westchester County Historic Sites in Westchester County Associated with the Revolutionary War Constance M. Kehoe, President: [email protected] Erik Weiselberg, Ph.D., Principal Historian: [email protected] Note: This list is a work in progress. The authors are interested in comments and suggestions. Copyright © Revolutionary Westchester 250, Inc. May 1, 2020 Proposals for filming locations and other places of interest Criteria Historic significance – major events and contributions of Westchester Photogenic – nice spot for a photo, video or interview Easily visited by the public (parking, restroom, easy access, etc.) Representative (from across the county, and all aspects of the war) Otherwise significant/recognized (for ex., status as state or federal historic site) Signage, monuments, preservation efforts, etc. (especially recently installed or updated) Miller House, White Plains – Washington’s Headquarters, 1776 The Miller House served as headquarters for General George Washington and others during the Battle of White Plains, the largest battle of the war in the Westchester and a decisive one for the course of the war. At one time a museum and center for interpreting the Revolutionary War era, the house just underwent a $3.5 million repair, with contributions from the county and some from the state. Ann Fisher Miller, wife of Elijah Miller, acted as a hostess to Continental Army generals, including George Washington, who used the house as a headquarters, particularly during the Battle of White Plains, October 1776. Miller’s two boys signed up for the patriot cause but died of disease early in the war.