The Hudson River Valley Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Revised Standard Version Bible with Apocrypha: Genuine Leather Black Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE NEW REVISED STANDARD VERSION BIBLE WITH APOCRYPHA: GENUINE LEATHER BLACK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK NRSV Bible Translation Committee | 1616 pages | 17 Oct 2006 | Oxford University Press Inc | 9780195288315 | English | New York, United States The New Revised Standard Version Bible with Apocrypha: Genuine Leather Black PDF Book Enter email address. This ebook is a selective guide designed to help scholars and students of criminology find reliable sources of information by directing them to the best available scholarly materials in whatever form or format they appear from books, chapters, and journal A: This Bible is printed in Korea. Approximately 85 alterations to the RSV text were authorized in and introduced into the printings. In an effort to further ecumenical relations, the more extensive 50th Anniversary Edition also included some of the preferred Catholic readings in the text and footnotes of the New Testament section. Review this product Share your thoughts with other customers. Featuring an attractive and sturdy binding, this pew Bible will give years of dependable service. Christian Living. This fascinating exploration of Leonardo da Vinci's life and work identifies what it was that made him so unique, and explains the phenomenon of the world's most celebrated artistic genius who, years on, still grips and inspires us. Color maps and a presentation page. Verified Purchase. Sign in or create an account. Harold W Attridge. Members save with free shipping everyday! Q: Is this a full catholic bible with all 73 books and in the right order? New Revised Standard Version. Large print. Main category: Bible translations into English. Related Searches. -

ANTHRACITE Downloaded from COAL CANALS and the ROOTS of AMERICAN FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE, 1820–1860 Envhis.Oxfordjournals.Org

CHRISTOPHER F. JONES a landscape of energy abundance: ANTHRACITE Downloaded from COAL CANALS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE, 1820–1860 envhis.oxfordjournals.org ABSTRACT Between 1820 and 1860, the construction of a network of coal-carrying canals transformed the society, economy, and environment of the eastern mid- Atlantic. Artificial waterways created a new built environment for the region, an energy landscape in which anthracite coal could be transported cheaply, reliably, at Harvard University Library on October 26, 2010 and in ever-increasing quantities. Flush with fossil fuel energy for the first time, mid-Atlantic residents experimented with new uses of coal in homes, iron forges, steam engines, and factories. Their efforts exceeded practically all expec- tations. Over the course of four decades, shipments of anthracite coal increased exponentially, helping turn a rural and commercial economy into an urban and industrial one. This article examines the development of coal canals in the ante- bellum period to provide new insights into how and why Americans came to adopt fossil fuels, when and where this happened, and the social consequences of these developments. IN THE FIRST DECADES of the nineteenth century, Philadelphians had little use for anthracite coal.1 It was expensive, difficult to light, and considered more trouble than it was worth. When William Turnbull sold a few tons of anthracite to the city’s waterworks in 1806, the coal was tossed into the streets to be used as gravel because it would not ignite.2 In 1820, the delivery © 2010 The Author. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Society for Environmental History and the Forest History Society. -

May 1975 Vol. XXII, No. 2

Masonic Culture Workshops Scheduled In Four Areas The PENNSYLVANIA To Assist Lodge Officers The Grand Lodge Committee on Ma sonic Culture has divided the Jurisdic FREE1VIASON tion into four areas, one more than was previously announced. AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL GRAND LODGE OF Masonic Culture Seminars are being FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS OF PENNSYLVANIA conducted in these areas to assist Lodge Officers to prepare interesting Lodge meetings. The agenda for the Seminars covers VOLUME XXII MAY • 1975 NUMBER 2 introduction materials and services pro vided by the Grand Lodge Committee "Rededication Month" on Masonic Culture. 197 6 Lodge Programs A " Packet" of informative papers, pamphlets and other helpful guides is Are Being Distributed Five members of the Rodd family, all Officers of Chartiers Lodge No. 297, Canonsburg, are being distributed to those attending the Grand Master Calls Craft to Labor shown with Bro. Eugene G. Painter, District Deputy Grand Master for the 29th Masonic District. Front row, left to right: Bro. Robert C. Rodd, Senior Deacon; Bro. Painter, and Bro. Seminars. October has been designated " Re John T. Rodd, Worshipful Master. Rear row, left to right: Bro. John R. Rodd, Past Master The four Area Chairmen, Members of dedication to Freemasonry" Month by By District Deputies and Secretary; Bro. Howard J. Orr, Past Master and Secretary Emeritus and cousin of Bro. the Grand Lodge Committee on Masonic John R. Rodd; and Bro. Robert C. Rodd II, Junior Warden. Bro. John R. Rodd is the father the Grand Master. of the three Rodds. Culture, are responsible for the follow In making the announcement, Bro. -

Matthew Herrald

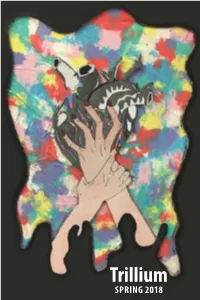

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre

The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet THE CLASSIC SHORT STORY The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Florence Goyet This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that she endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Goyet, Florence. The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925: Theory of a Genre. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0039 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available on our website at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-75-6 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-76-3 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-77-0 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-78-7 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-79-4 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0039 Cover portraits (left to right): Henry James, Flickr Commons (http://www.flickr.com/photos/7167652@ N06/2871171944/), Guy de Maupassant, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guy_ de_Maupassant_fotograferad_av_Félix_Nadar_1888.jpg), Giovanni Verga, Wikimedia (http:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catania_Giovanni_Verga.jpg), Anton Chekhov, Wikimedia (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anton_Chekov_1901.jpg) and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Akutagawa_Ryunosuke_photo.jpg). -

V 52, #1 Fall 2015

THE SOCIETY OF THE CINCINNATI NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE Cincinnati fourteen 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. P A I D fourteen Cincinnati Washington, DC 20008-3640 WASHINGTON, DC PERMIT NO. 8805 Volume 52, Volume No.1 Fall 2015 Fall 2015 Members and guests of the New Hunter Lowell Davis, son of Pennsylvania Society member Brad Jersey and Pennsylvania societies Davis and grandson of former president Lowell Davis, was admitted convened on April 25 on a perfect as a successor member this fall. A student at the Friends School in Spring Saturday for a tour of Fort Baltimore, Hunter is spending the fall at the prestigious School for Mifflin, south of Philadelphia. The New Ethics and Global Leadership in Washington. The Davis family Jersey group started at Fort Mercer traces its lineage to two brothers who served as officers in the on the eastern bank of the Delaware Pennsylvania line. River and were joined by the Pennsylvanians at Fort Mifflin on Mud Island on the western bank. Lunch Friends of Independence National Historical Park; “We want as little busing to get to venues as was served inside the fort, followed by the National Park Service; Bartram’s Gardens possible,” said Jim Pringle, the state society’s vice a guided tour of the stone fortress and (oldest surviving botanic garden in North president. “By staying in the historic district, we demonstration of musketry and America); the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; can minimize all forms of transportation,” Pringle Revolutionary War cannon. The the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, Free and explained. “We will concentrate the activities so dogged defense of Fort Mifflin by Accepted Masons; The Barnes Foundation (art they’re easily walkable, as much as possible.” American soldiers under constant museum); and The Barnes Arboretum (gardens). -

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library

639 Bedford Rd Pocantico Hills, NY 10591 [email protected] Library The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection Finding Aid Collection Overview Title: The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012 (bulk 1808-1896) Creator: Osterweis, Rollin G. (Rollin Gustav), 1907- Extent : 159 volumes; 1 linear foot of archival material Repository: Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives Abstract: This collection holds 159 volumes that make up the Rollin G. Osterweis Collection of Irving Editions and Irvingiana. It also contains one linear foot of archival materials related to the collection. Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Item title. (date) City: Publisher [if applicable]. The Rollin G. Osterweis Washington Irving Collection, 1808-2012, (Date of Access). Historic Hudson Valley Library and Archives. Historic Hudson Valley. Provenance: This collection was created by Rollin Gustav Osterweis and donated to Historic Hudson Valley by Ruth Osterweis Selig. 18 December 2012. Access: This collection is open for research with some restrictions based on the fragility of certain materials. Research restrictions for individual items are available on request. For more information contact the Historic Hudson Valley librarian, Catalina Hannan: [email protected]. Copyright: Copyright of materials belongs to Historic Hudson Valley. Permission to reprint materials must be obtained from Historic Hudson Valley. The collection contains some material copyrighted by other organizations and individuals. It is the responsibility of the researcher to obtain all permission(s) related to the reprinting or copying of materials. Processed by: Christina Neckles Kasman, February-August 2013 Osterweis Irving Collection - 1 Biographical Note Rollin Gustav Osterweis was a native of New Haven, Connecticut, where his grandfather had established a cigar factory in 1860. -

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: ___________________ National Touring Production of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow to Perform Locally Bright Star Touring Theatre, a national professional touring theatre company based in Asheville, NC, is visiting the area with their performance of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow- In this fun-filled retelling of Washington Irving’s classic tale, the bumbling schoolmaster Ichabod Crane is in love with Katrina Van Tassel, the loveliest girl in town. Katrina, however, happens to be in love with the town prankster, Brom Bones. Crane refuses to give up, but his pursuit of Katrina finds him face to face with the legendary headless horseman on a stormy night—or is this just another prank by Brom Bones? Your audience will especially love watching several volunteers become members of the Sleepy Hollow town choir. Enjoyed by audiences across the United States, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is best appreciated by audiences in grades 2-6. Each year, Bright Star Touring Theatre serves nearly 2,000 audiences in schools, theaters, libraries, museums and more across the country. They offer a wide variety of curriculum-based programs ranging from The Lady of Bullyburg to Heroes of the Underground Railroad. The company performs regularly at the National Theatre in Washington, DC and has gained international attention, having visited Russia and Germany with their productions. Bright Star is committed to providing professional theatre to audiences at an affordable and all-inclusive rate. Information about all their interactive shows, including production videos, photos, study guides, and more, is available online at www.brightstartheatre.com, or contact Bright Star Theatre directly at 336-558-7360. -

The Freeman 1999

Ideas On Liberty July 1999 Vol. 49, No.7 I 8 THOUGHTS on FREEDOM-Outside the Limits by Donald J. Boudreaux 8 Immoral, Unconstitutional War by David N Mayer 1 12 The Kosovo Tangle by Gary Dempsey 16 Remembering and Inventing: A Short History of the Balkans by Peter Mentzel 21 POTOMAC PRINCIPLES-Warmongering for Peace by Doug Bandow 23 Isolationism by Frank Chodorov 26 How War Amplified Federal Power in the Twentieth Century by Robert Higgs 30 Another Place, Another War by Michael Palmer 32 War's Other Casualty by Wendy McElroy 137 Spontaneous Order by Nigel Ashford 43 Storm Trooping to Equality by James Bovard 48 Croaking Frogs by Brian Doherty 81 Noah Smithwick: Pioneer Texan and Monetary Critic by Joseph R. Stromberg 38 IDEAS and CONSEQUENCES-Clinton versus Cleveland and Coolidge on Taxes by Lawrence W. Reed 41 THE THERAPEUTIC STATE-Suicide as a Moral Issue by Thomas Szasz 148 ECONOMIC NOTIONS-In the Absence ofPrivate Property Rights by Dwight R. Lee 54 ECONOMICS on TRIAL-Dismal Scientists Score Another Win by Mark Skousen 63 THE PURSUIT of HAPPINESS-Ignorance Is Bliss-Maybe by Walter Williams 2 Perspective-Operation Legacy by Sheldon Richman 4 Tax Cuts Are Unfair? It Just Ain't So! by David Kelley 58 Book Reviews Overcoming Welfare: Expecting More from the Poor and Ourselves by James L. Payne, reviewed by Robert Batemarco; Coolidge: An American Enigma by Robert Sobel and The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge by Robert Ferrell, reviewed by Raymond 1. Keating; H. L. Mencken Revisited by William H. A. Williams, reviewed by George C. -

Kittanning Medal Given by the Corporation of Tlie City of Philadelphia

Kittanning Medal given by the Corporation of tlie City of Philadelphia. Washington Peace Medal presented to Historical Society of Pennsylvania March 18, 188i> by Charles C. CresBon. He bought two (this a'nd the Greeneville Treaty medal) for $30.00 from Samuel Worthington on Sept 2!>. 1877. Medal belonged to Tarhee (meaning The Crane), a Wyandot Chief. Greeneville Treaty Medal. The Order of Military Merit or Decoration of the Purple Heart. Pounded Try General Washington. Gorget, made by Joseph Richardson, Jr., the Philadelphia silversmith. THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY. VOL. LI. 1927. No. 2. INDIAN AND MILITARY MEDALS FROM COLONIAL TIMES TO DATE BY HARROLD E. GILLINGHAM.* "What is a ribbon worth to a soldier? Everything! Glory is priceless!" Sir E. B. Lytton, Bart. The nature of man is to demand preferences and distinction. It is uncertain who first instituted the custom of granting medals to individuals for acts of bravery or for military services. Scipio Aemilius is said to have bestowed wreaths of roses upon his men of the eleventh Legion at Carthage in 146 B. C., and the Chinese are reported to have issued awards during the Han Dynasty in the year 10 A. D., though no de- scription thereof is given. Tancred says there used to be in the National Coin Collection of France, a gold medal of the Roman Emperor Tetricus, with loops at- tached, which made it appear as if it was an ornament to wear. Perhaps the Donum Militare, and bestowed for distinguished services. We do know that Queen Elizabeth granted a jewelled star and badge to Sir Francis Drake after his famous globe encircling voy- age (1577-1579), and Tancred says these precious relics were at the Drake family homestead, "Nutwell * Address delivered before the Society, January 10, 1927 and at the meeting of The Numismatic and Antiquarian Society February 15, 1926. -

The Rockefellers an Enduring Legacy

The Rockefellers An Enduring Legacy 90 / OCTOBER 2012 / WWW.WESTCHESTERMAGAZINE.COM alfway through a three-hour tour The views from Kykuit were astound- of the Kykuit mansion, the for- ing—possibly the best in Westchester. The mer home to four generations Hudson sparkled like a thousand stars lit up of Rockefellers, it became appar- in the night sky. Surrounding towns, includ- ent that I was going to need to ing Tarrytown and Sleepy Hollow, looked as Huse the bathroom—a large mug of iced coffee if civilization had yet to move in, the tree- purchased at a Tarrytown café was to blame. tops hiding any sign of human life. I felt like My guide, Corinne, a woman of perhaps 94, a time-traveler whisked back to a bygone era. Look around eagerly led me to a marble bathroom enclosed This must have been the view that had in- by velvet ropes, telling me this may have been spired John D. Rockefeller to purchase land you. How where John D. Rockefeller had spent a great in Westchester in 1893. New York City, where deal of his time. When, after several high- the majority of the Rockefeller family resided, much of decibel explanations, she gathered the nature was just 31 miles away and a horse-drawn car- of my request, I was ushered away from the riage could make the journey to the estate in the land, tour by two elderly women carrying walkie- less than two hours. It was the perfect family talkies, taken down a long flight of wooden retreat, a temporary escape from city life. -

And Early Twentieth Centuries

A Broker's Duty of Best Execution in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Francis J. Facciolo' Introduction Although a broker-dealer's duty of best execution can now be located in federal common law, self-regulatory organization ("SRO") regulations, or state common law, the root of the doctrine is conventionally found in the third area, state law. In this view, the common law duty of best execution is a particular manifestation of a broker's more general duties as an agent to its customers.1 The duty of best execution may be broadly characterized as a fiduciary one, or as a2 limited duty, due with respect only to a particular purchase or sale. Even in jurisdictions where a broker is not a fiduciary, however, courts require brokers, as agents, to give best execution to their customers.3 One well known treatise has summarized the common law duty of best execution as consisting of three things: "the duty to execute promptly; the duty to execute in an appropriate market; and the duty to obtain the best price.'A Different types of customers put differing . Francis J. Facciolo is on the faculty of the St. John's University School of Law. The Author thanks Maria Boboris and David J. Grech for their research assistance; William H. Manz and the St. John's University School of Law library staff for their generous help in locating many obscure research materials; Dean Mary C. Daly for a summer research grant, which enabled me to start this article; and Professor James A. Fanto for his insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article that was presented at Pace Law School's Investor Rights Symposium.