How Was Hsitorical Imagery Sued in the Propagnda Posters of the European Powers of the Second World War?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikolai Dolgorukov

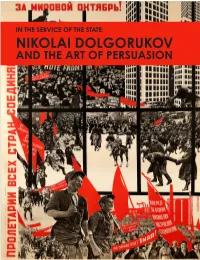

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Propagandamoldova

Issue 1(11), 2018 MYTHS MYTHS NEWS TARGET AUDIENCE GEORGIA IMAGE INFLUENCE ESTONIA NARRATIVES MEDIA DISINFORMATION CRISIS HISTORY INFORMATION PROPAGANDA HISTORY COMMUNICATIONS RUSSIA IMAGE UKRAINE MOLDOVA OPERATIONS NEWS FAKE NEWS EUROPE TURKEY INFLUENCE INFORMATION TV MYTHS UA: Ukraine CRISISAnalytica · 1 (11), 2018 • DISINFORMATION CAMPAIGNS • FAKE NEWS • INFLUENCE OPERATIONS 1 BOARD OF ADVISERS Dr. Dimitar Bechev (Bulgaria, Director of the European Policy Institute) Issue 1 (11), 2018 Dr. Iulian Chifu Analysis and Early Warning Center) (Romania, Director of the Conflict Propaganda Amb., Dr. Sergiy Korsunsky (Ukraine, Director of the Diplomatic Academy under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine) Dr. Igor Koval (Ukraine, Rector of Odessa National Editors University by I.I. Mechnikov) Dr. Hanna Shelest Dr. Mykola Kapitonenko Amb., Dr. Sergey Minasyan (Armenia, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Armenia to Romania) Publisher: Published by NGO “Promotion of Intercultural Marcel Rothig (Germany, Director of the Cooperation” (Ukraine), Centre of International Representation of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Ukraine) of the Representation of the Friedrich Ebert Studies (Ukraine), with the financial support Foundation in Ukraine, and the Black Sea Trust. James Nixey (United Kingdom, Head of the Russia and Eurasia Programme at Chatham House, the UA: Ukraine Analytica Royal Institute of International Affairs) analytical journal in English on International is the first Ukrainian Relations, Politics and Economics. The journal Dr. Róbert Ondrejcsák (Slovakia, State Secretary, is aimed for experts, diplomats, academics, Ministry of Defence) students interested in the international relations and Ukraine in particular. Amb., Dr. Oleg Shamshur (Ukraine, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine Contacts: to France) website: http://ukraine-analytica.org/ e-mail: [email protected] Dr. -

Worcester Historical

Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11 Hawthorne Street Worcester, Massachusetts ARCHIVES 2019.01 Kline Collection Processd by Casey Bush January 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Series Page Box Collection Information 3 Historical/Biographical Notes 4 Scope and Content 4 Series Description 5 1 Anti-Semitic material 7-15 1-2, 13 2 Holocaust material 16-22 2-3, 13 3 Book Jackets 23 4-9 4 Jewish History material 24-29 10-11, 13 5 Post-war Germany 30-32 12 6 The Second World War & Resistance 33-37 28 7 French Books 38-41 14 8 Miscellaneous-language materials 42-44 15 9 German language materials 45-71 16-27 10 Yiddish and Hebrew language materials 72-77 29-31 11 Immigration and Refugees 78-92 32-34 12 Oversized 93-98 35-47 13 Miscellaneous 99-103 48 14 Multi-media 104-107 49-50 Appendix 1 108 - 438 2 Collection Information Abstract : This collection contains books, pamphlets, magazines, guides, journals, newspapers, bulletins, memos, and screenplays related to anti-Semitism, German history, and the Holocaust. Items cover the years 1870-1990. Finding Aid : Finding Aid in print form is available in the Repository. Preferred Citation : Kline Collection – Courtesy of The Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts. Provenance : Purchased in 1997 from Eric Chaim Kline Bookseller (CA) through the generosity of the following donors: Michael J. Leffell ’81 and Lisa Klein Leffell ’82, the Sheftel Family in memory of Milton S. Sheftel ’31, ’32 and the proceeds of the Carole and Michael Friedman Book Fund in honor of Elisabeth “Lisa” Friedman of the Class of 1985. -

Theatrical Spectatorship in the United States and Soviet Union, 1921-1936: a Cognitive Approach to Comedy, Identity, and Nation

Theatrical Spectatorship in the United States and Soviet Union, 1921-1936: A Cognitive Approach to Comedy, Identity, and Nation Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Pamela Decker, MA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Jennifer Schlueter Frederick Luis Aldama Copyright by Pamela Decker 2013 Abstract Comedy is uniquely suited to reveal a specific culture’s values and identities; we understand who we are by what and whom we laugh at. This dissertation explores how comic spectatorship reflects modern national identity in four theatre productions from the twentieth century’s two rising superpowers: from the Soviet Union, Evgeny Vakhtangov’s production of Princess Turandot (1922) and Vsevolod Meyerhold’s production of The Bedbug (1929); from the United States, Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s Broadway production of Shuffle Along (1921) and Orson Welles’ Federal Theatre Project production of Horse Eats Hat (1936). I undertake a historical and cognitive analysis of each production, revealing that spectatorship plays a participatory role in the creation of live theatre, which in turn illuminates moments of emergent national identities. By investigating these productions for their impact on spectatorship rather than the literary merit of the dramatic text, I examine what the spectator’s role in theatre can reveal about the construction of national identity, and what cognitive studies can tell us about the spectator’s participation in live theatre performance. Theatre scholarship often marginalizes the contribution of the spectator; this dissertation privileges the body as the first filter of meaning and offers new insights into how spectators contribute and shape live theatre, as opposed to being passive observers of an ii already-completed production. -

November 2020. New Acquisitions, Boston Antiquarian Book Fair & Gems Under $500 F O R E W O R D

NOVEMBER 2020. NEW ACQUISITIONS, BOSTON ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR & GEMS UNDER $500 F O R E W O R D Dear friends, We are happy to share with you our new catalogue, a product of our latests searches and acquisitions. Items from this catalogue will be featured in our booth at the Virtual Boston Book Fair which openes November 12 (check their website for more info bostonbookfair.com). We have a vast and interesting geography in this catalogue: from Cuba (#14) to Soviet Arctic (#26), books on Soviet-Chinese relationship (#27) and Soviet-Japanese conflicts (#15 & 16) as well as photos of Central Asia in #12, Iranian art and archeology (#9), folklore of Crimean Tatars (#33), Georgian book about American George Washington (#19), a small but powerful section of Judaica (#17 and 18), Ukrainian books (#3, 4, 13), traces of German (#1 & 39) and others. Last but not least in this catalogue is the section ‘‘Gems Under $500’’ which has 7 items for your consideration from Soviet architecture (#36) and art theory (#34) to a circus poster (#40) and Armenian Soviet propaganda (#38). The section starts on p. 66! Other chapters of this catalogue are more classical: Architecture (p. 6), Printing Arts (p. 39), Women (p. 25), Photo Books (p. 49), Science (p. 53), et al. A few curious items are hidden in Miscellaneous section, for exmaple, fortune telling cards (#31) or tutorial on how to make your own shoes (#32). We hope you’ll enjoy this time and space travel through our catalogue! Stay well and safe, Bookvica & Globus Books team November 2020 BOOKVICA 2 Bookvica 15 Uznadze St. -

To Examine the Immediate Causes of World War

US History, April 29 • Entry Task: Many students have to finish the test (sit in one area). • Everyone else: Grab a book (p. 734), read the section, and answer # 2,3,4 (page 741). • Announcements: – Extra Credit for Spirit Days – 1 pt per day (Sign up on paper – if I forgot to pass it around one day, go ahead and fill in!) – Roaring 20s-Great Depression tests–A = 64.5+, B = 57.5+, C = 50.5+, D = 43.5+ US History, May 4 • Entry Task: None today – make sure you’ve turned in everything! • Announcements: – Assignment from Thursday: Read Chapter 24 sections 1 & 2 – answer # 2, 3, 4 on page 741 and # 2 & 5 and define appeasement on page 747. – Assignment from Friday: Map – Test Corrections are due! See me for questions. Japan: Emperor Hirohito • Known as “Tenno” to his subjects, the living embodiment of the Japanese people • Symbol of the state more than an actual ruler • People never heard his voice until August 15, 1945 • Hideki Tojo was Prime Minister of Japan 1941-1944 Japan • Japan felt that they had the right to start an overseas empire, just as European countries such as Britain and France had. •Why did Japan “need” overseas territories? •(1)In 1931, Japan seized Manchuria, China, for its valuable coal and iron. (2) Puppet state created: Manchukuo • The League of Nations condemned actions but failed to help China. (3) Japan simply dropped out of the League. • (4) In 1937, Japan began an all out attack on China (Rape of Nanking), eventually conquering (5) Korea and (6) French Indo-China (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos) as well by 1941. -

The Personality Cult Of

THE PERSONALITY CULT OF STALININ SOVIET POSTERS, 1929–1953 ARCHETYPES, INVENTIONS & FABRICATIONS THE PERSONALITY CULT OF STALININ SOVIET POSTERS, 1929–1953 ARCHETYPES, INVENTIONS & FABRICATIONS ANITA PISCH Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Pisch, Anita, author. Title: The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 - 1953 : archetypes, inventions and fabrications / Anita Pisch. ISBN: 9781760460624 (paperback) 9781760460631 (ebook) Subjects: Stalin, Joseph, 1879-1953--Symbolism. Political posters, Russian. Symbolism in politics--Soviet Union. Symbolism in mass media. Symbolism in art. Dewey Number: 741.670947 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image adapted from: ‘26 years without Lenin, but still on Lenin’s path’, Mytnikov, 1950, Izdanie Rostizo (Rostov-Don), edn 15,000. This edition © 2016 ANU Press CES Prize This publication was awarded a Centre for European Studies Publication Prize in 2015. The prize covers the cost of professional copyediting. Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of illustrations . ix Abbreviations . xxi Introduction . 1 1 . The phenomenon of the personality cult — a historical perspective . 49 2 . The rise of the Stalin personality cult . 87 3 . Stalin is like a fairytale sycamore tree — Stalin as a symbol . 191 4 . Stalin saves the world — Stalin and the evolution of the Warrior and Saviour archetypes . -

Soviet Brochure for Pdf.Indd

DAVID WINTON BELL GALLERY, BROWN UNIVERSITY VIEWS and RE-VIEWS SOVIET POLITICAL POSTERS AND CARTOONS WELCOME through 3 2 INTRODUCTION 7 4 through ESSAY through 16 8 WORKS 20 17through VIEWS and RE-VIEWS SOVIET POLITICAL POSTERS AND CARTOONS On view at the David Winton Bell Gallery and the John Hay Library Gallery September 6 — October 19, 2008 Auxiliary selections from the collection are on view at the Cogut Center for the Humanities and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library through 2008 LEFT BORIS KLINCˇ Sponsored by the David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University Library, Cogut Center “Fire hard at the class enemy!” 1933 for the Humanities, and Office of the Vice President for International Affairs COVER MIKHAIL BALJASNIJ PHOTOS Boston Photo Imaging and Brown University Library Digital Production Services “Communism means soviets [popular councils], plus the electrification of the whole country. 1 DESIGN Malcolm Grear Designers Let us transform the USSR through socialist industrialization” (detail), 1930 BACK COVER ALEXANDER ZHITOMIRSKY ISBN 0-933519-49-4 Hysterical War Drummer, 1948 Copyright © 2008 David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University These images remind us that the music, art, RE-VIEWS and literature of the mid-to-late Soviet period have often been scorned as politically coerced, their creators to be pitied, and and only occasionally admired for their bold aesthetics. VIEWS and RE-VIEWS invites us to reconsider that tradition, perhaps in light of our own era’s rigidities of politics and taste. Perhaps if we imagine the difficulty of untangling the flurry of media images, communication, and miscommunication surrounding our national election, we TO VIEWS may glimpse something of the tortuous labyrinth required to appreciate the real a powerful sampling of more than and unreal in these posters and cartoons. -

Russia and USA: Rhetoric and Reality By: Dmitry V

Russia and USA: Rhetoric and Reality by: Dmitry V. Shlapentokh, Ph.D. oralization is an essential part of any geo-political game, and that is especially Mthe case with countries such as the United States and Russia. Presently, Washington has become especially prone to playing the morality card. At least, that is the case with Hillary Clinton supporters who stated that the ugliness of Donald Trump is clearly manifested by his desire to overlook the noble principles on which American foreign policy has rested since the founding fathers designed it. Consequently, Trump’s desire to befriend Vladimir Putin, the authoritarian Russian President, is a clear departure from his basic principles. Moscow also likes to assure that Russia always follows high moral principles in its foreign policy design. Still, Kremlin residents mostly limited moralizing to an internal audience, whereas people in Washington made the moralization publicly known to an international audience, urbis and orbis, so to speak. A closer look at the Soviet/Russia and the U.S. relationship could reveal that it is not high principles, whatever they might be in the context of the prevailing ideological shibboleth, but rather it is pragmatism that defines their relationship. The image of both countries has followed the pragmatic model. This implies that the U.S. and Russia could well cooperate in the future despite hostile rhetoric that dominated discourse in Moscow and Washington – a rhetoric that might not disappear completely in the future. The Early Encounters: The Origins of the Images Let us start with the beginning of the Bolshevik Revolution. Most Americans and, in some ways, the entire Western elite regarded the Bolsheviks in the same way most regarded present-day ISIS. -

A TRAGIC TRICKSTER 151 the Trickster As the Underground Author 154 Rituals of Expenditure 167 “I Will Not Explain to You Who Were These Four…” 174

——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— CHARMS OF THE CYNICAL REASON: THE TRICKSTER’S TRANSFORMATIONS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET CULTURE — 1 — ——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— Cultural Revolutions: Russia in the Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Anthony Anemone (The New School) Robert Bird (The University of Chicago) Eliot Borenstein (New York University) Angela Brintlinger (The Ohio State University) Karen Evans-Romaine (Ohio University) Jochen Hellbeck (Rutgers University) Lilya Kaganovsky (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) Christina Kiaer (Northwestern University) Alaina Lemon (University of Michigan) Simon Morrison (Princeton University) Eric Naiman (University of California, Berkeley) Joan Neuberger (University of Texas, Austin) Ludmila Parts (McGill University) Ethan Pollock (Brown University) Cathy Popkin (Columbia University) Stephanie Sandler (Harvard University) Boris Wolfson (Amherst College), Series Editor — 2 — ——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— CHARMS OF THE CYNICAL REASON: THE TRICKSTER’S TRANSFORMATIONS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET CULTURE Mark Lipovetsky Boston 2011 — 3 — A catalog data for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2011 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-45-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-618111-35-7 (digital) Effective June 20, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, -

The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953

THE PERSONALITY CULT OF STALININ SOVIET POSTERS, 1929–1953 ARCHETYPES, INVENTIONS & FABRICATIONS THE PERSONALITY CULT OF STALININ SOVIET POSTERS, 1929–1953 ARCHETYPES, INVENTIONS & FABRICATIONS ANITA PISCH Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Pisch, Anita, author. Title: The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929 - 1953 : archetypes, inventions and fabrications / Anita Pisch. ISBN: 9781760460624 (paperback) 9781760460631 (ebook) Subjects: Stalin, Joseph, 1879-1953--Symbolism. Political posters, Russian. Symbolism in politics--Soviet Union. Symbolism in mass media. Symbolism in art. Dewey Number: 741.670947 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image adapted from: ‘26 years without Lenin, but still on Lenin’s path’, Mytnikov, 1950, Izdanie Rostizo (Rostov-Don), edn 15,000. This edition © 2016 ANU Press CES Prize This publication was awarded a Centre for European Studies Publication Prize in 2015. The prize covers the cost of professional copyediting. Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of illustrations . ix Abbreviations . xxi Introduction . 1 1 . The phenomenon of the personality cult — a historical perspective . 49 2 . The rise of the Stalin personality cult . 87 3 . Stalin is like a fairytale sycamore tree — Stalin as a symbol . 191 4 . Stalin saves the world — Stalin and the evolution of the Warrior and Saviour archetypes . -

The Law of the Wolf How the Kukryniksy Trio Represented the Enemy As a “Wild” Animal in Cold War Political Cartoons in Pravda, 1965–1982

ARTIKKELIT Reeta Kangas THE LAW OF THE WOLF How the Kukryniksy Trio Represented the Enemy as a “Wild” Animal in Cold War Political Cartoons in Pravda, 1965–1982 The Law of the Wolf: How the Kukryniksy Trio Represented the Enemy as a “Wild” Animal in Cold War Political Cartoons in Pravda, 1965–1982 This article examines how the Soviet Kukryniksy trio used wild animals in their political cartoons to depict the enemies of the Soviet Union. The primary material of this research consists of Kukryniksy’s 39 wild animal cartoons published in Pravda during 1965–1982. I discuss these cartoons within the theoretical framework of frame analysis and propaganda theory. According to frame analysis, we see the world through certain frames, which affect the way we interpret what is happening. Thus, it is important to bear in mind that what people perceive is dependent on their cultural frameworks. These frameworks can be used in propaganda to manipulate our perceptions and affect our behaviour. In this article I demonstrate what kind of symbolic functions wild animals have in these cartoons and what kind of characteristics they attach to the enemies depicted. Furthermore, I examine in what kind of frames the world was to be seen according to the Communist Party ideology, and how these frames were created with the use of wild animal characters. In these cartoons wild animals are used to reveal the ”true” nature of the enemy. The animal’s symbolic functions may derive from the linguistic or other cultural contexts. The cartoons depict the enemy mainly as deceptive and ruthless, but simultaneously predictable to the Soviet Union.