Affect and Humour on Gossip Blogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna: Reina Del Pop... Y De Los Escándalos

6D EXPRESO Domingo 27 de Abril de 2008 eSTELAR Perez Hilton De a FAN CELEBRIDAD “Trabajo mucho y siempre tengo Gracias a su blog, Perez Hilton se ha acercado nueva información. Además, siempre tengo exclusivas y fui de los primeros en utilizar el formato del blog para in- a las estrellas de Hollywood sin temor y las exhibe formar sobre celebridades. Otra clave es que observo a Hollywood desde el interior y tengo una perspectiva dis- cada vez que puede, pero, ¿él podrá soportar la crítica? tinta”, confiesa. Perez publica exclusivas, incluso antes de que revistas como People lo Salvador Cisneros “Perez Hilton es sólo un persona- hagan. Él fue el primero en hacer pú- publicar que Lance Bass, vocalista de je y la gente no conoce mi verdadera blica la relación de Jessica Simpson y El blog de Perez Hilton se *NSYNC, y Neil Patrick Harris, prota- mado por millones de per- personalidad”, asegura el bloggero vía John Mayer. caracteriza porque en las gonista de Doogie Howser,eranho- sonas que festejan la irre- telefónica desde Los Ángeles. Sin embargo, acepta (a medias) fotografías que publica mosexuales. verencia con la que criti- Y tiene razón. Su voz es calmada que a veces se equivoca porque es hace anotaciones o dibujos “Sé con certeza que algunas ce- Aca a los hollywoodenses y y antes de contestar se toma unos se- humano. que tienden a ridiculizar a lebridades son gays y con otras sólo odiado por centenares de celebrida- gundos para reflexionar las pregun- “Escribí que Fidel Castro falleció los famosos. me gusta bromear al respecto. -

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY Interview for Not Making It Clear That He Wasn't the Father of the Baby She Miscarried Last May

Love's Story The combative singer-actress embarks on a legal skirmish with her record label that may change what it means to be a rock star. Oh, and she also has some choice words about her late husband's bandmates, her newfound ancestry, Russell Crowe, Angelina Jolie... By Holly Millea | Mar 25, 2002 Image credit: Courtney Love Photographs by Jean Baptiste Mondino COURTNEY LOVE IS IN A LIMOUSINE TAKING HER FROM Los Angeles to Desert Hot Springs on a detox mission. "I've been on a bit of a bender after 9/11," she admits. "I've got a lot of s--- in me. I weigh 147 pounds." Which is why she's checking into the We Care colonic spa for five days of fasting. Slumped low in the seat, the 37-year-old actress and lead singer of Hole is wearing baggy faded jeans, a brown pilled sweater, and Birkenstock sandals, her pink toenails twinkling with rhinestones. On her head is a wool knit hat - 1 - that looks like something she found on the street. Last night she sat for three hours while her auburn hair extensions were unglued and cut out. "See?" Love says, pulling the cap off. "I look like a Dr. Seuss character on chemo." She does. Her hair is short and tufty and sticking out in all directions. It's a disaster. Love smiles a sad, self-conscious smile and covers up again. Lighting a cigarette, she asks, "Why are we doing this story? I don't have a record or a movie to promote. -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

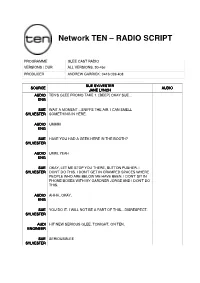

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

14. Swan Song

LISA K. PERDIGAO 14. SWAN SONG The Art of Letting Go in Glee In its five seasons, the storylines of Glee celebrate triumph over adversity. Characters combat what they perceive to be their limitations, discovering their voices and senses of self in New Directions. Tina Cohen-Chang overcomes her shyness, Kurt Hummel embraces his individuality and sexuality, Finn Hudson discovers that his talents extend beyond the football field, Rachel Berry finds commonality with a group instead of remaining a solo artist, Mike Chang is finally allowed to sing, and Artie Abrams is able to transcend his physical disabilities through his performances.1 But perhaps where Glee most explicitly represents the theme of triumph over adversity is in the series’ evasion of death. The threat of death appears in the series, oftentimes in the form of the all too real threats present in a high school setting: car accidents (texting while driving), school shootings, bullying, and suicide. As Artie is able to escape his wheelchair to dance in an elaborate sequence, if only in a dream, the characters are able to avoid the reality of death and part of the adolescent experience and maturation into adulthood. As Trites (2000) states, “For many adolescents, trying to understand death is as much of a rite of passage as experiencing sexuality is” (p. 117). However, Glee is forced to alter its plot in season five. The season begins with a real-life crisis for the series; actor Cory Monteith’s death is a devastating loss for the actors, writers, and producers as well as the series itself. -

The Life & Near Death Story of Patty Schemel

REVIEWS "Describing the parabolic ups and downs of the career of Hole drummer Patty Schemel, tricked-up docu Hit So Hard features never-before-witnessed tour documentation recorded on Schemel's own Hi-8 camera, including her extended stay at the digs of band frontwoman Courtney Love just before Kurt Cobain's suicide. This recently recovered ace-in-the-Hole footage is supplemented by helmer P. David Ebersole's newly shot interviews, presented in split-screen or apportioned in brief bursts. Pic benefits from the percussionist's plainspokenness, and should attract grunge curiosity-seekers in theatrical and tube play." VARIETY "A raw, unflinching look at Schemel's hard-knock life." WALL STREET JOURNAL "Necessary viewing for any Hole fan. The footage was ample and intimate -- scenes of Schemel passed out in her hotel room after shooting heroin, Love moshing backstage at Lollapalooza with the Offspring's Dexter Holland and, most eerily, Love at home with Kurt Cobain and Frances Bean. It's heartbreaking." SPIN MAGAZINE "Hit So Hard links one milestone of Schemel’s survival to another with a caustic grace lent by the subject herself: Alcoholic at age 12. Out, tormented lesbian at 17. Junkie by her early 20s. On and off the wagon numerous times by her late 20s. A homeless, crack-addicted, music-industry exile by the end of the ’90s. It’s all there in the open, backed up with fascinating, never-before-seen archival footage featuring Love and her husband Kurt Cobain." MOVIELINE "This pull-no-punches portrait of the hell-and-back life of Patty Schemel is no ordinary rockumentary. -

INTRODUCTION Hello, Bitches! Perez Hilton, the Queen of All Media, Here!

INTRODUCTION Hello, bitches! Perez Hilton, the Queen of All Media, here! I wouldn’t be a self-proclaimed Hilton without penning a book of my own, now, would I? After all, I went through my own rite of passage and gained access to the crazy, sensational celebrity world. But I thought to myself, “Why should I have all the fun?” Like Paris, I’d like to make this world a hotter place. So this book, my friends, was writ- ten for you. In these pages, I’ll show you what it takes to reach celebrity status, and how, with a few wobbly steps and a case of Astroglide, you too can be a hilton! I don’t mean that you should be a street-corner whore (but you’re definitely getting warmer!). No, what I mean is, you can live like the rich, famous, and utterly depraved without even an ounce of talent or dignity. Tired Reid is a good example of a hilton success story. I can’t even remember the last real work she’s done. After all those horrible movies, train-wreck media appearances, and documented drunken partying, you’d think she’d be banned from Hollywood forever. But somehow she still finds her way into magazines and is even popular in Australia! How can someone who’s made suicide moves to her “career”—on the red carpet, no less—still get attention? It’s because she be- longs to the Hilton generation of Hollywood, and for these hiltons, scandalous behavior is actually not a suicide attempt at all. -

An Appraisal Analysis of Gossip News Texts Written by Perez Hilton from Perezhilton.Com (A Study Based on Systemic Functional Li

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id An Appraisal Analysis of Gossip News Texts Written By Perez Hilton From Perezhilton.com (A Study Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics) THESIS Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment for Requirements for the Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Department Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts Sebelas Maret University BY: Clara Ertyas P. C0306022 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LETTERS AND FINE ARTS SEBELAS MARET UNIVERSITY SURAKARTA commit2011 to user i perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user ii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user iii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id PRONOUNCEMENT Name : Clara Ertyas P. NIM : C0306022 Herewith, it is declared that this thesis entitled “An Appraisal Analysis of Gossip News Texts Written by Perez Hilton from Perezhilton.com (A Study Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics)” is completed by the researcher, not by others. It is not a plagiarism and it never becomes a thesis previously. Everything related to other people’s works, which are published or not, the sources of them are placed in the bibliography. If it is then proven that the researcher cheats, the researcher is ready to take the responsibility. Surakarta, The researcher Clara Ertyas P. commit to user iv perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id MOTTO If I was the kind to have regrets, I wouldn't be doing what I'm doing. -Perez Hilton- commit to user v perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: Everyone who loves me and everyone I love commit to user vi perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Praises for Jesus Christ as His blessings lead and guide the researcher and hence this thesis can be completed. -

Harris, Neil Patrick (B

Harris, Neil Patrick (b. 1973) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Neil Patrick Harris in Entry Copyright © 2009 glbtq, Inc. 2008. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Photograph by Kristin Dos Santos. Image appears under the Neil Patrick Harris earned celebrity as a teen-ager for his starring role in the television Creative Commons series Doogie Howser, M.D. Unlike many child actors, he has made a successful Attribution ShareAlike transition to mature roles, showcasing his singing and dancing abilities along the way. 2.0 License. Since coming out publicly in 2006, he has also spoken out on behalf of glbtq causes. Harris was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico on June 15, 1973. His parents, Ron and Sheila Harris, are both lawyers, and his mother is also a writer. As a fourteen-year-old, Harris attended a drama camp at New Mexico State University, where he met writer Mark Medoff, who was working on a project that became the film Clara's Heart (1988), directed by Robert Mulligan. Soon Harris began his professional acting career with roles in Linda Shayne's Purple People Eater (1988) and Mulligan's Clara's Heart. His performance in the latter won him a Golden Globe nomination in the category of Supporting Actor. In 1989 he became the star of the television "dramedy" series Doogie Howser, M.D., which was about a precocious youngster who had become a doctor at the age of fourteen. In the opening episode, sixteen- year-old Doogie interrupted the road test for his driver's license to attend to an accident victim. -

GOSSIP SELLS the GOODS Celebrities and the Paparazzi Are Now in the Business Plan

GOSSIP SELLS THE GOODS Celebrities and the paparazzi are now in the business plan BY ANNE KINGSTON (MACLEAN’S AUG.4 ’08) Before last Wednesday, few people had heard of plainmary.com, a website selling posh baby gear. By week's end, the site had more than two million hits and had received orders from as far away as Dubai. Credit a tiny item in Rush & Molloy, a gossip column in the New York Daily News, that reported Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie had, six weeks earlier, ordered two of its US $190monogrammed mats for their then‐ unborn twins. What made the story buzz‐worthy was the news one of the mats had been ordered for "Rex Leon," not "Knox Leon," as their latest little boy is named, suggesting a last‐minute change of mind. The source of this breaking news? That would be Andy Behrman, plainmary.com's publicist, who learned gossip fundamentals writing for New York magazine. "It's critical for a company like plain mary to have celebrity associations," he says. "I mean who gives a s‐‐t about a plain mary baby mat? But, all of a sudden, if the tush of a sainted Jolie‐Pitt is peeing on this $190 microfibre mat, that's a $10,000 mat that we'll see on eBay shortly." Behrman comes to the job having sharpened his tabloid incisors repping Petit Trésor, the celebrity‐gossip‐fuelled Los Angeles purveyor of baby paraphernalia recently hyped in People's gushing coverage of Jennifer Lopez's Versailles‐style nursery. Its two stores have become go‐to destinations for paparazzi seeking "baby bumps," and the celebrities vying for their attention.