The Platform of the Temple of Venus and Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/85949 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-07 and may be subject to change. KLIO 92 2010 1 65––82 Lien Foubert (Nijmegen) The Palatine dwelling of the mater familias:houses as symbolic space in the Julio-Claudian period Part of Augustus’ architectural programme was to establish „lieux de me´moire“ that were specifically associated with him and his family.1 The ideological function of his female relativesinthisprocesshasremainedunderexposed.2 In a recent study on the Forum Augustum, Geiger argued for the inclusion of statues of women among those of the summi viri of Rome’s past.3 In his view, figures such as Caesar’s daughter Julia or Aeneas’ wife Lavinia would have harmonized with the male ancestors of the Julii, thus providing them with a fundamental role in the historical past of the City. The archaeological evi- dence, however, is meagre and literary references to statues of women on the Forum Augustum are non-existing.4 A comparable architectural lieu de me´moire was Augustus’ mausoleum on the Campus Martius.5 The ideological presence of women in this monument is more straight-forward. InmuchthesamewayastheForumAugustum,themausoleumofferedAugustus’fel- low-citizens a canon of excellence: only those who were considered worthy received a statue on the Forum or burial in the mausoleum.6 The explicit admission or refusal of Julio-Claudian women in Augustus’ tomb shows that they too were considered exempla. -

Tour of the Early Church: Journeys of Paul & John with Dr

Tour of the Early Church: Journeys of Paul & John with Dr. David Dockery Dr. Timothy George, Instructor May 22 - June 5, 2012 Day 1, Tue, May 22 DEPART USA and relatively inexpensive; and backgammon, the national We depart the USA today for our overnight journey to Istan- game of Turkey, is available in many different and unique bul. (meals aloft) sets. (B,D) Day 2, Wed, May 23 ARRIVE ISTANBUL Day 6, Sun, May 27 EPHESUS/KUSADASI We arrive to Istanbul and are met by our English-speaking We journey to Ephesus where Paul spent two years and guide and coach. We transfer to our hotel, the Hotel Golden which had become the capital city of the Roman Province of City, for dinner and overnight. (meals aloft,D) Asia by the time of John's ministry there near the end of the fist century. Ephesus as also the site of a most important Day 3, Thu, May 24 NICEA/ISTANBUL Church Council in 431 AD. We walk through history in a city Today we travel to Iznik, ancient Nicea, located in the north- founded as early as the 10th century B.C. In the magnificent east of Bursa on the side of Iznik Lake. Under Constantine excavations we see streets lined with wonderful public build- I when Christianity became the state religion, Nicea became ings such as the Baths of Scholastica, the Library of Celsus, an important religious center where two ecumenical councils the Temple of Hadrian, the Basilica of St. John, and the great were held, in 325 and 787 AD. -

The Capital of Roman Province of Asia-Ephesus

THE CAPITAL OF ROMAN PROVINCE OF ASIA-EPHESUS Location Ephesus is located between two hills with the silted ancient port and about three kms from Selcuk town. It belongs to greater Izmir province and 10 kms to Kusadasi, 65 kms to İzmir. The ancient town used to be the home of historical Greek and Roman ages so it grabs millions of visitors each year. There is a good connection to Ephesus from all over Turkey and it is only 40 minutes drive from the third biggest airport called as İzmir to Ephesus. Name The name comes from Hittite Word “ Apasas” due to Greek could not do the correct pronouncation so they converted it as Ephesus. It means “the bee “ so Ephesus was the city of the bee. The bee was minted on the coins dated 11th BC in Hittite period. History Ephesus has been known as the home of Greek Artemis, Roman Diana, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, used to be center of the paganism about one thousand years, later it became the first of the seven churches of Revelation. First Pagan then Christian pilgrims made Ephesus as the center of their faiths like Vatican today so it was visited by millions each year. On the other hand, The port of Ephesus was the central of sea trade in antiquity between Asia, Macedonia(Europe) and North Africa. The first settlement in the area was done by Amazons according to some legends but the findings shows us Ephesus was first founded by Hittites about 13 th C BC and it fell into Greek hand after the fall of Troy in 11 th BC by Greek commender Androklos . -

Foust Handout Images.Pdf

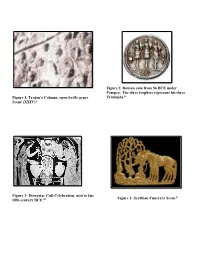

Figure 2. Roman coin from 56 BCE under Pompey. The three trophies represent his three Figure 1. Trajan’s Column, open battle genre Triumphs.ii Scene (XXIV) i Figure 3: Dionysiac Cult Celebration, mid to late Figure 2: Scythian Funerary Sceneiv fifth century BCE.iii Figure 3: Portonaccio Sarcophagus, 190-200 CE, National Museum of Rome, for a general of Marcus Aurelius, showing battle with the Sarmatians. The trophy on the right shows a face mask used in battle. Another relief on the column of M. Aurelius shows a trophy with this type of mask.v Figure 5: Reliefs of the Temple of Hadrian, held at the National Archaeology Museum of Naples.vi Figure 6: Victory carrying the standard of military success from Hadrian’s temple on the Campus Martius, 145 CE, the location where the Roman Triumphs began.vii i From http://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/trajans-column/the-project/numbering-conventions-and-site-guide/, Univ. of Saint Andrews, [accessed 6 July 2017]. ii Image from ancient Coin Search Engine; a similar coin also appears in Beard, The Roman Triumph, 20. iii https://www.britannica.com/topic/mystery-religion, Louvre, Paris. iv https://www.thecultureconcept.com/scythians-warriors-of-ancient-siberia-british-museum-show. v Open source image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portonaccio_sarcophagus. vi http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=7303 From the Temple of Hadrian on the Campus Martius, dates to 145 CE. (Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli). This represents another image of a trophy. vii From http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=7300 from http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/art-search-e.htm. -

Waters of Rome Journal

THE CLOACA MAXIMA AND THE MONUMENTAL MANIPULATION OF WATER IN ARCHAIC ROME John N. N. Hopkins [email protected] Introduction cholars generally conceive of the Cloaca Maxima as a Smassive drain flushing away Rome’s unappealing waste. This is primarily due to the historiographic popularity of Imperial Rome, when the Cloaca was, in fact, a sewer. By the time Frontinus assumed the post of curator aquarum in 97 AD, its concrete and masonry tunnels channeled Rome’s refuse beneath the Fora and around the hills, and stood among extensive drainage networks in the valleys of the Circus Maximus, Campus Martius and Transtiberim (Figs. 1 & 2).1 Built on seven hundred years of evolving hydraulic engineering and architecture, it was acclaimed in the first century as a work “for which the new magnificence of these days has scarcely been able to produce a match.”2 The Cloaca did not, however, always serve the city in this manner. Archaeological and literary evidence suggests that in the sixth century BC, the last three kings of Rome produced a structure that was entirely different from the one historians knew under the Empire. What is more, evidence suggests these kings built it to serve entirely different purposes. The Cloaca began as a monumental, open-air, fresh-water canal (Figs. 3 & 4). This canal guided streams through the newly leveled, paved, open space that would become the Forum Romanum. In this article, I reassess this earliest phase of the Cloaca Maxima when it served a vital role in changing the physical space of central Rome and came to signify the power of the Romans who built it. -

Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: the Timeless

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2013 Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: The imelesT s Allure of the Farnese Antinous Kathleen LaManna Scripps College Recommended Citation LaManna, Kathleen, "Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: The imeT less Allure of the Farnese Antinous" (2013). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 176. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/176 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POWER AND NOSTALGIA IN ERAS OF CULTURAL REBIRTH: THE TIMELESS ALLURE OF THE FARNESE ANTINOUS by KATHLEEN ROSE LaMANNA SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MICHELLE BERENFELD PROFESSOR GEORGE GORSE MAY 3, 2013 Acknowledgements To Professor Rankaitis for making sure I could attend the college of my dreams and for everything else. I owe you so much. To Professor Novy for encouraging me to pursue writing. Your class changed my life. Don’t stop rockin! To Professor Emerick for telling me to be an Art History major. To Professor Pohl for your kind words of encouragement, three great semesters, and for being the only person in the world who might love Gladiator more than I do! To Professor Coats for being a great advisor and always being around to sign my many petition forms and for allowing me to pursue a degree with honors. -

Volume 63 February, 1989 Number 2 ROME, 1988 by Eileen Torrence At

Volume 63 February, 1989 Number 2 ROME, 1988 by Eileen Torrence At Horace's Sabine Farm, we listened to presenta tions and recitations by group members and by guest Professor Eleanor Winsor Leach; we climbed to Fons Bandusiae to cool our feet and to play in its magical, musical waters. On another outing, the brave scaled Mt. Soracte in the rain (which I must confess I bypassed to visit a medieval Italian village). And of course, there were daily excursions through the hills of Rome. During these perambulations, especially when I missed the bus, the words of Vergil reverberated in my ears and pulse! "... facilis descensus... /sed revocare gradum superasque evadare ad auras,/hoc opus, hie labor est." But every step up was worth the effort, and I felt as though I were on top of the world when I celebrated my 25th birthday on the 25th of July, standing at the top of Trajan's Column! Gerhard "spiraled" us through as much of the Dacian Wars as daylight permitted. The expressions of horror and pain on the faces of the wounded and dying were disturbing, while the depictions of villages, camps, At the base of Trajan's Column, Rome, Italy. bridges, and aqueducts refined my textbook knowledge and understanding of these structures. I kept my camera The 1988 Summer Session at the American Academy busy during this privileged visit, and I shall always treas in Rome was literally filled with "highs" and "lows," and ure the unique photo opportunity of the Imperial Fora and all were magnificent illustrations of the complex structure the Markets of Trajan. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Achilles (subject) 42–43, 140, 156, 161, 170, 291; Arches Basilica 81 Figs. 2.23, 6.26, 10.19 Arc de Triomphe, Paris 359–360; Aemilia 135–136; Fig. 5.22 acroterion 33, 37, 39; Fig. 2.14 Fig. 12.26 Constantine, Trier 338–339; Figs. 12.4–12.5 Actaeon (subject) 176, 241; Figs. 6.33, 8.34 Arcus Novus, Rome 311 Nova, Rome 340; Figs. 12.6–12.7 Adamclisi, Tropaeum Traiani 229–230; of Argentarii, Rome 287; Figs. 10.14, 10.15 Pompeii 81–83; Figs. 4.5, 4.6 Figs. 8.20–8.21 of Constantine, Rome 341–346; Severan, Lepcis Magna 296, 299; adlocutio 116, 232, 256; Figs. 5.2, 8.24, 9.13 Figs. 12.8–12.11 Figs. 10.26–10.27 adventus 63, 203, 228, 256, 313, 350; of Galerius, Thessalonica 314–315; Ulpia, Rome 216; Fig. 8.5 Figs. 7.25, 8.23 Figs. 11.15–11.16 Baths aedicular niche 133; Fig. 5.20 of Marcus Aurelius, Rome 256; Fig. 9.13 of Agrippa, Rome 118, 185, 279 aedile 12 of Septimius Severus, Lepcis of Caracalla, Rome 279–283; Aemilius Paullus 16, 65, 126 Magna 298–299; Figs. 10.28, 10.29 Figs. 10.7–10.10 Victory Monument 16, 107–108; of Septimius Severus, Rome 284–286; of Cart Drivers, Ostia 242–244; Fig. 8.37 Figs. 4.30, 4.31 Figs. 10.11–10.13 of Diocletian, Rome 320–322; Aeneas 27, 121, 122, 126, 127, 135, 140, 156, of Titus, Rome 201–203; Figs. 7.22–7.24 Figs. -

The Footsteps of the Great Apostle

17 50th Anniversary Celebration Pilgrimage DAYS OUR LADY OF THE ROSARY, KELLYVILLE Accompanied by FR ALEJANDRO LOPEZ, OFM CONV. & The footsteps of FR LEONIDES MATEO, the Great Apostle OFM CONV. 14 NIGHTS / 17 DAYS. DEPARTS FRIDAY 14TH MAY 2021 Athens (2) • Cruise: Mykonos, Ephesus, Patmos, Rhodes, Crete, Santorini (4) • Corinth (1) • Hosios Loukas • Meteora • Kalambaka (2) • Berea • Kavala • Philippi • Thessaloniki (2) • Istanbul • Canakkale (1) • Istanbul (2). Optional Franciscan Extension to Italy - 9 nights SANTORINI HAGIA SOFIA, ISTANBUL SYMBOLS: (B) Breakfast, (L) Lunch (D) Dinner the Virgin Mary RHODES Our excursion today will include Ephesus, Today we come to the Island of Rhodes, where DAY 1: FRIDAY 14 MAY - DEPART AUSTRALIA the most famous of the Seven Churches of St Paul came during his third missionary DAY 2: SATURDAY 15 MAY - ARRIVE ATHENS Revelation (Rev 2:1-7) where St Paul spent journey (Acts 21:1). We enter the port, which more than two years in the course of his third was once dominated by the Colossus, one of Athens today is the thriving capital of Greece, missionary journey. It was to the Christian the seven wonders of the ancient world. but, more importantly, we have entered into community of Ephesus that St Paul wrote Shore Excursion: Rhodes & Lindos the world of the New Testament where St his greatest and most challenging letter (the Paul and his companions established the first Lindos is situated 55 km from the city of epistle to the Ephesians) and succeeded in Christian communities throughout his four Rhodes and “bears” above it the Acropolis of converting many away from worship of the missionary journeys. -

Centro Storico

PDF Rome Centro Storico (PDF Chapter) Edition 9th Edition, Jan 2016 Pages 37 Page Range 70–97, 214–222 COVERAGE INCLUDES: Useful Links • Neighbourhood Top • Sleeping Five Want more guides? Head to our shop • Local Life • Getting There & Trouble with your PDF? Away Trouble shoot here • Sights Need more help? • Eating Head to our FAQs • Drinking & Nightlife Stay in touch • Entertainment Contact us here • Shopping © Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. To make it easier for you to use, access to this PDF chapter is not digitally restricted. In return, we think it’s fair to ask you to use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. In other words, please don’t upload this chapter to a peer-to-peer site, mass email it to everyone you know, or resell it. See the terms and conditions on our site for a longer way of saying the above – ‘Do the right thing with our content’. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 70 Centro Storico PANTHEON | PIAZZA NAVONA | CAMPO DE’ FIORI | JEWISH GHETTO | ISOLA TIBERINA | PIAZZA COLONNA Neighbourhood Top Five io o rz anz 0000 a Bri a COLON0000NA M a n 0000 e i Vi t f c 1 gt on n Lu 0000 Stepping into the L M i a 0000 i ro ia d tti V 0000 ia c refe del Co 0000 Pantheon (p72) and feeling P V S ei d 0000 a ia l 0000 the same sense of awe that l V 0000 V e ia dell'O rs rso d the ancients must have felt o a i V 2000 years ago. -

Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Art History THE HADRIANIC TONDI ON THE ARCH OF CONSTANTINE: NEW PERSPECTIVES ON THE EASTERN PARADIGMS A Dissertation in Art History by Gerald A. Hess © 2011 Gerald A. Hess Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 The dissertation of Gerald A. Hess was reviewed and approved* by the following: Elizabeth Walters Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Associate Professor of Art History Brian Curran Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head, Department of Art History Donald Redford Professor of Classics and Mediterranean Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation is a study of the impact of eastern traditions, culture, and individuals on the Hadrianic tondi. The tondi were originally commissioned by the emperor Hadrian in the second century for an unknown monument and then later reused by Constantine for his fourth century arch in Rome. Many scholars have investigated the tondi, which among the eight roundels depict scenes of hunting and sacrifice. However, previous Hadrianic scholarship has been limited to addressing the tondi in a general way without fully considering their patron‘s personal history and deep seated motivations for wanting a monument with form and content akin to the prerogatives of eastern rulers and oriental princes. In this dissertation, I have studied Hadrian as an individual imbued with wisdom about the cultural and ruling traditions of both Rome and the many nations that made up the vast Roman realm of the second century.