The Myths of Christopher Isherwood | the New York Review of Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Isherwood Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0gr7 No online items Christopher Isherwood Papers Finding aid prepared by Sara S. Hodson with April Cunningham, Alison Dinicola, Gayle M. Richardson, Natalie Russell, Rebecca Tuttle, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2, 2000. Updated: January 12, 2007, April 14, 2010 and March 10, 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Christopher Isherwood Papers CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Christopher Isherwood Papers Dates (inclusive): 1864-2004 Bulk dates: 1925-1986 Collection Number: CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 Creator: Isherwood, Christopher, 1904-1986. Extent: 6,261 pieces, plus ephemera. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of British-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), chiefly dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. Consisting of scripts, literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, ephemera, audiovisual material, and Isherwood’s library, the archive is an exceptionally rich resource for research on Isherwood, as well as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and others. Subjects documented in the collection include homosexuality and gay rights, pacifism, and Vedanta. Language: English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department, with two exceptions: • The series of Isherwood’s daily diaries, which are closed until January 1, 2030. -

An Index to Alan Ansen's the Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited By

An Index to Alan Ansen’s The Table Talk of W. H. Auden Edited by Nicholas Jenkins Index Compiled by Jacek Niecko A Supplement to The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 20 • June 2000 Jacek Niecko is at work on a volume of conversations and interviews with W. H. Auden. Adams, Donald James 68, 115 Christmas Day 1941 letter to Aeschylus Chester Kallman 105 Oresteia 74 Collected Poems (1976) 103, 105, Akenside, Mark 53 106, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, Amiel, Henri-Frédéric 25 114, 116, 118 Andrewes, Lancelot 75 Collected Poetry 108 Meditations 75 Dark Valley, The 104 Sermons 75 Dog Beneath the Skin, The 51, 112 Aneirin Dyer’s Hand, The xiii, 100, 109, 111 Y Gododdin 108 “Easily, my dear, you move, easily Ann Arbor, Michigan 20, 107 your head” 106 Ansen, Alan ix-xiv, 103, 105, 112, 115, Enemies of a Bishop, The 22, 107 117 English Auden, The 103, 106, 108, Aquinas, Saint Thomas 33, 36 110, 112, 115, 118 Argo 54 Forewords and Afterwords 116 Aristophanes For the Time Being 3, 104 Birds, The 74 Fronny, The 51, 112 Clouds, The 74 “Greeks and Us, The” 116 Frogs, The 74 “Guilty Vicarage, The” 111 Aristotle 33, 75, 84 “Hammerfest” 106 Metaphysics 74 “Happy New Year, A” 118 Physics 74 “I Like It Cold” 115 Arnason Jon “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” xv, 70 Icelandic Legends 1 “In Search of Dracula” 106 Arnold, Matthew xv, 20, 107 “In Sickness and In Health” 106 Asquith, Herbert Henry 108 “In the Year of My Youth” 112 Athens, Greece 100 “Ironic Hero, The” 118 Atlantic 95 Journey to a War 105 Auden, Constance Rosalie Bicknell “Law Like Love” 70, 115 (Auden’s mother) 3, 104 Letter to Lord Byron 55, 103, 106, Auden, Wystan Hugh ix-xv, 19, 51, 99, 112 100, 103-119 “Malverns, The” 52, 112 “A.E. -

Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood

Prague Journal of English Studies Volume 8, No. 1, 2019 ISSN: 1804-8722 (print) '2,10.2478/pjes-2019-0005 ISSN: 2336-2685 (online) A Bond Stronger Than Marriage: Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood Kinga Latała Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland is paper is concerned with Christopher Isherwood’s portrayal of his guru-disciple relationship with Swami Prabhavananda, situating it in the tradition of discipleship, which dates back to antiquity. It discusses Isherwood’s (auto)biographical works as records of his spiritual journey, infl uenced by his guru. e main focus of the study is My Guru and His Disciple, a memoir of the author and his spiritual master, which is one of Isherwood’s lesser-known books. e paper attempts to examine the way in which a commemorative portrait of the guru, suggested by the title, is incorporated into an account of Isherwood’s own spiritual development. It discusses the sources of Isherwood’s initial prejudice against religion, as well as his journey towards embracing it. It also analyses the facets of Isherwood and Prabhavananda’s guru-disciple relationship, which went beyond a purely religious arrangement. Moreover, the paper examines the relationship between homosexuality and religion and intellectualism and religion, the role of E. M. Forster as Isherwood’s secular guru, the question of colonial prejudice, as well as the reception of Isherwood’s conversion to Vedanta and his religious works. Keywords Christopher Isherwood; Swami Prabhavananda; My Guru and His Disciple; discipleship; guru; memoir e present paper sets out to explore Christopher Isherwood’s depiction of discipleship in My Guru and His Disciple (1980), as well as relevant diary entries and letters. -

CONTENTS Xiii Xxxi Paid on Both Sides

CONTENTS PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi INTRODUCTION xiii THE TEXT OF THIS EDITION xxxi PLAYS Paid on Both Sides [first version] (1928), by Auden 3 Paid on Both Sides [second version] (1928), by Auden 14 The Enemies of a Bishop (1929), by Auden and Isherwood 35 The Dance of Death (1933), by Auden 81 The Chase (1934), by Auden 109 The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), by Auden and Isherwood 189 The Ascent of F 6 (1936), by Auden and Isherwood 293 On the Frontier (1937-38), by Auden and Isherwood 357 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Coal Face (1935) 421 Night Mail (1935) 422 Negroes (1935) 424 Beside the Seaside (1935) 429 The Way to the Sea (1936) 430 The Londoners (1938?) 433 CABARET AND WIRELESS Alfred (1936) 437 Hadrian's Wall (7937) 441 APPENDICES I Auden and Isherwood's "Preliminary Statement" (1929) 459 1. The "Preliminary Statement" 459 2. Auden's "Suggestions for the Play" 462 VI CONTENTS II The Fronny: Fragments of a Lost Play (1930) 464 III Auden and the Group Theatre, by M J Sldnell 490 IV Auden and Theatre at the Downs School 503 V Two Reported Lectures 510 Poetry and FIlm (1936) 511 The Future of Enghsh Poetic Drama (1938) 513 fEXTUAL NOTES PaId on Both SIdes 525 The EnemIes of a BIshop 530 The Dance of Death 534 1 History, Editions, and Text 534 2 Auden's SynopsIs 542 The Chase 543 The Dog Beneath the Skm 553 1 History, Authorship, Texts, and EditIOns 553 2 Isherwood's Scenano for a New Version of The Chase 557 3 The Pubhshed Text and the Text Prepared for Production 566 4 The First (Pubhshed) Version of the Concludmg Scene 572 5 Isherwood's -

Goodbye to Berlin: Erich Kästner and Christopher Isherwood

Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association ISSN: 0001-2793 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjli19 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE To cite this article: YVONNE HOLBECHE (2000) GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD, Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 94:1, 35-54, DOI: 10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 Published online: 31 Mar 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 33 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjli20 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KASTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE University of Sydney In their novels Fabian (1931) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), two writers from different European cultures, Erich Mstner and Christopher Isherwood, present fictional models of the Berlin of the final years of the Weimar Republic and, in Isherwood's case, the beginning of the Nazi era as wel1. 1 The insider Kastner—the Dresden-born, left-liberal intellectual who, before the publication ofFabian, had made his name as the author not only of a highly successful children's novel but also of acute satiric verse—had a keen insight into the symptoms of the collapse of the republic. The Englishman Isherwood, on the other hand, who had come to Berlin in 1929 principally because of the sexual freedom it offered him as a homosexual, remained an outsider in Germany,2 despite living in Berlin for over three years and enjoying a wide range of contacts with various social groups.' At first sight the authorial positions could hardly be more different. -

On the Poetry of the Dog Beneath the Skin

GSJ: Volume 7, Issue 6, June 2019 ISSN 2320-9186 870 GSJ: Volume 7, Issue 6, June 2019, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com ON THE POETRY OF THE DOG BENEATH THE SKIN Associate Prof. Yahya Saleh Hasan Dahami English Department, Faculty of Science and Arts – Al Mandaq AL BAHA UNIVERSITY, Al Baha KSA [email protected] [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0195-7878 Abstract The Dog Beneath the Skin is the first play to be coauthored between Wystan Hugh Auden and Christopher Isherwood. It is a play written in verse, which creates a challenge of success for the dramatists for two reasons, the first is that it deals with verse, the second it is collaborative. The study through the collaborators, trying to show, to what extent, both achieved attainment in dealing with verse drama. This study also endeavors to trace the poetic features in The Dog Beneath the Skin and to attempt proving the capability and controllability in writing successful drama in verse through collaboration. This paper is done by using an analytic-critical method. It is an approach to a drama shared by both Auden and Isherwood. The study tersely traces the growth and elaboration of poetic drama until the twentieth century. It goes through the sort of collaboration between Auden and Isherwood. It is concluded by examining and analyzing, its central part, the poetic features and essentials in the play The Dog Beneath the Skin. Key Words: Auden and Isherwood, collaboration, literature, poetic drama, The Dog Beneath the Skin, twentieth century GSJ© 2019 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 7, Issue 6, June 2019 ISSN 2320-9186 871 Introduction It is believed that poetic dramas possess the facility to break into the sources of sentiment and action of people all over the ages. -

Peter Alexander B

parrasch heijnen gallery 1326 s. boyle avenue los angeles, ca, 90023 www.parraschheijnen.com 3 2 3 . 9 4 3 . 9 3 7 3 Peter Alexander b. 1939 in Los Angeles, California Lives in Santa Monica, California Education 1965-66 University of California, Los Angeles, CA, M.F.A. 1964-65 University of California, Los Angeles, CA, B.A. 1963-64 University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 1962-63 University of California, Berkeley, CA 1960-62 Architectural Association, London, England 1957-60 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA Artist in Residence 2007 Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA 1996 California State University Long Beach, Summer Arts Festival, Long Beach, CA 1983 Sarabhai Foundation, Ahmedabad, India 1982 Centrum Foundation, Port Townsend, WA 1981 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 1976 California State University, Long Beach, CA 1970-71 California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA Select Solo Exhibitions 2020 Peter Alexander, Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2018 Peter Alexander: Recent Work, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne, Germany 2017 Peter Alexander: Pre-Dawn L.A., Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Peter Alexander Sculpture 1966 – 2016: A Career Survey, Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Los Angeles Riots, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2014 Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA The Color of Light, Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA 2013 Nyehaus, New York, NY Quint Contemporary Art, La Jolla, CA -

44-Christopher Isherwood's a Single

548 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2020.S8 (November) Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life / G. Güçlü (pp. 548-562) 44-Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life Gökben GÜÇLÜ1 APA: Güçlü, G. (2020). Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 548-562. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.816962. Abstract Beginning his early literary career as an author who nurtured his fiction with personal facts and experiences, many of Christopher Isherwood’s novels focus on constructing an identity and discovering himself not only as an adult but also as an author. He is one of those unique authors whose gradual transformation from late adolescence to young and middle adulthood can be clearly observed since he portrays different stages of his life in fiction. His critically acclaimed novel A Single Man, which reflects “the afternoon of his life;” is a poetic portrayal of Isherwood’s confrontation with ageing and death anxiety. Written during the early 1960s, stormy relationship with his partner Don Bachardy, the fight against cancer of two of his close friends’ (Charles Laughton and Aldous Huxley) and his own health problems surely contributed the formation of A Single Man. The purpose of this study is to unveil how Isherwood’s midlife crisis nurtured his creativity in producing this work of fiction. From a theoretical point of view, this paper, draws from literary gerontology and ‘the Lifecourse Perspective’ which is a theoretical framework in social gerontology. -

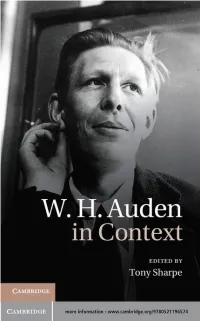

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

First Name Initial Last Name

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Sarah E. Fass. An Analysis of the Holdings of W.H. Auden Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2006. 56 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper is an analysis of the monographic works by noted twentieth-century poet W.H. Auden held by the Rare Book Collection (RBC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It includes a biographical sketch as well as information about a substantial gift of Auden materials made to the RBC by Robert P. Rushmore in 1998. The bulk of the paper is a bibliographical list that has been annotated with in-depth condition reports for all Auden monographs held by the RBC. The paper concludes with a detailed desiderata list and recommendations for the future development of the RBC’s Auden collection. Headings: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 – Bibliography Special collections – Collection development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF W.H. AUDEN MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION by Sarah E. Fass A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

The Novels of Christopher Isherwood

• - '1 .' 1 THE NOVELS OF CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD " .r -----------------------~------ ---------- ( ~ .... 'o( , • 1 • , \ J .. .. .J., .. ~ 'i':;., t , • ) .. \ " NARCISSUS OBSERVED AND OBSERVING: THE NOVELS OF C~RISTOPHER 1SI'lERWOOD " By Wiltiam Aitken , / Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Master of Arts Degree . Department of'English ~J • ~1cG i 11 Uni ve~s i ty '. , 2 August 1974 .'J . f .' '. li ' . .~ ~ 4-' '\ .. • .( 1 , 1975 ABSTRACT \ • 1, • "Narcissis Obser,\ed and,Observing: The Novels of ~hristoPhe'r Isherwood" deals with narcissi~... --both limitless and limited--as a constant theme running through the novels of Christopher Isher'(fOod. Narcissism is examined in its mythical and psychoanalytlcal contexts, with special emphasis given to the writings of Freud and Marcuse. Par ticular attention is paid~to the author's homosexuality and his various works that deal with homosexuality: an attempt is made to show how » nârcissism may function as a vital and invaluable creative asset for the homosexual author. RESUME "Narc1sse observé et observant: Les Roman~de Christopher r - Isherwood. 11 Cet ouvrage démontre que le narcissisme (à la fois limité et sans limites) est, un thème constant des romans ~e Christopher Ishe~ wood. le phénomêne du narci~sisme est analysé dans ses contextes mythiques et psychanalytiques avec une insistance particuli~re sur les oeuvres de Freud et de Marcuse. L'étude porte un~ attentlon sp€ciale" "à llhomos~xualité de l'auteur et à ses oeuvres diverses et essaie de montrer comment le narcissisme peut être une source d'lnspiration ( v~ta1e et inestimable pour l'écrivain homasexuel . • • PREFACE 1 wish to thank Professor Donald Rùbin for his h~lp a~d suggestions concerning Isherwood's works and pertinent backgr~nd t mate~ia11 a1so, Professor Bruce Garside for his guidance concerning narcissism and psychoanalytic theory. -

Berthold Viertel

Katharina Prager BERTHOLD VIERTEL Eine Biografie der Wiener Moderne 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Veröffentlicht mit der Unterstützug des Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : PUB 459-G28 Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative-Com- mons-Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0; siehe http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung : Berthold Viertel auf der Probe, Wien um 1953; © Thomas Kuhnke © 2018 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Korrektorat : Alexander Riha, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Umschlaggestaltung : Michael Haderer, Wien ISBN 978-3-205-20832-7 Inhalt Ein chronologischer Überblick ....................... 7 Einleitend .................................. 19 1. BERTHOLD VIERTELS RÜCKKEHR IN DIE ÖSTERREICHISCHE MODERNE DURCH EXIL UND REMIGRATION Außerhalb Österreichs – Die Entstehung des autobiografischen Projekts 47 Innerhalb Österreichs – Konfrontationen mit »österreichischen Illusionen« ................................. 75 2. ERINNERUNGSORTE DER WIENER MODERNE Moderne in Wien ............................. 99 Monarchisches Gefühl ........................... 118 Galizien ................................... 129 Jüdisches Wien ..............................