Journaloffthreaftenedtaxa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley

Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh A Dissertation submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By MOHAN SHARMA Department of Geography School of Human Sciences February 2020 Date: 07/02/2020 DECLARATION I, Mohan Sharma, hereby declare that the research work embodied in the Dissertation titled “Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh” submitted to Sikkim University for the award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy, is my original work. The thesis has not been submitted for any other degree of this University or any other University. (Mohan Sharma) Roll Number: 18MPGP01 Regd. No.: 18MPhil/GOG/01 Name of the Department: Geography Name of the School: Human Sciences Date: 07/02/2020 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled “Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh” submitted to Sikkim University for the partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Geography, embodies the result of bonafide research work carried out by Mr. Mohan Sharma under our guidance and supervision. No part of the dissertation has been submitted for any other degree, diploma, associateship and fellowship. All the assistance and help received during the course of the investigation have been duly acknowledged by him. We recommend -

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

The Phylogenetic Relationship of the Muskox and Takin Based on High Resolution, G-Banded, Chromosome Analysis

Paper presented at The First Arctic Ungulate Conference, Nuuk, Greenland, 3-8 September, 1991. Expanded abstract The phylogenetic relationship of the muskox and takin based on high resolution, G-banded, chromosome analysis M. Pasitschniak-Arts1, P. F. Flood2, S. M. Schmutz3, S. Tedesco2 and B. Seidel4 1 Department of Biology, 2 Department of Veterinary Anatomy, and 3 Department of Animal and Poultry Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada S7N 0W0. 4 Tierpark Berlin-Friedrichsfelde, Am Tierpark 125, D-1136 Berlin, Germany Key words: muskox, takin, chromosomes, G-banded karyotypes Rangifer, 12 (3) 203-205 Muskoxen, Ovibos moschatus, currently inhabit The relationship of the muskox to other parts of the Canadian mainland tundra, nume• members in the Bovidae is somewhat unclear. rous Arctic islands, regions of Alaska, Norway, Many related genera of bovids adapted to cold• Sweden, northern and eastern Greenland, and er climates are now extinct, leaving only the the Taymyr Peninsula (Lent, 1988). The takin, muskox and takin (Jia-Yan, 1989; Lent, 1988; Budorcas taxicolor, is an Asian species presently Neas and Hoffman, 1987). Despite the apparent found in mountainous areas of west central close relatedness of the two species, banded ka• China, Burma, Bhutan and India Qia-Yan, 1989; ryotypes of the muskox and takin have yet to Neas and Hoffman, 1987). Both species appear be compared. to have originated from a common ancestor in In the Bovidae, individual autosome pairs can• Asia and exhibit morphological similarities. not be reliably distinguished using conventional Muskoxen apparently dispersed from north cen• staining (Lin et aL, 1977), but they have been tral Asia to North America during the Illinoian identified using G-banding (Wang and Federoff, glaciation Qia-Yan, 1989). -

Dry Season Diets of Sympatric Ungulates in Lowland Nepal: Competition and Facilitation in Alluvial Tall Grasslands

Ecol Res (2006) 21:698–706 DOI 10.1007/s11284-006-0177-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Per Wegge Æ Anil K. Shrestha Æ Stein R. Moe Dry season diets of sympatric ungulates in lowland Nepal: competition and facilitation in alluvial tall grasslands Received: 8 November 2005 / Accepted: 3 February 2006 / Published online: 17 May 2006 Ó The Ecological Society of Japan 2006 Abstract Based on microhistological analyses of faecal Keywords Hog deer Æ Swamp deer Æ Rhinoceros Æ material, we compared the early dry season diets of Elephant Æ Axis porcinus Æ Cervus duvauceli Æ greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis, Rhinoceros unicornis Æ Elephas maximus Æ Diet Æ swamp deer Cervus duvauceli and hog deer Axis porci- Food competition Æ Resource partitioning nus, which inhabit the same alluvial grassland habitat complex in lowland Nepal. Their diets were quite simi- lar, both at the forage category level and within sub- categories of graminoids and woody plants. Early Introduction successional tall grasses, especially Saccharum sponta- neum, were the dominant food of all three species, Interspecific interactions among sympatric ungulates, underlining the key role of the threatened alluvial such as food competition and resource partitioning, are floodplains in large mammal conservation in South much debated issues in theoretical ecology and practical Asia. The two deer species ate significantly more wildlife management (White 1978; Caughley and Sinclair graminoids (>66.5%) than did rhino (45.5%), and al- 1994; Putman 1996; Abrams 1998; Murray and Illius though they did not differ in proportions of graminoids, 2000; Arsenault and Owen-Smith 2002). Because re- swamp deer ate significantly more late successional tall source use overlap in terms of habitat and diet is a useful grasses (Narenga porphyrocoma and Themeda spp.) and approach to understanding such interactions (Schoener short grasses (mainly Imperata cylindrica) than hog deer. -

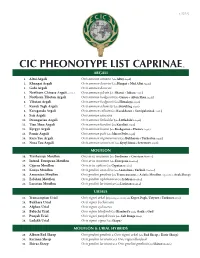

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Royle Safaris Sichuan Mammals Tour Trip Report

In March 2019 Royle Safaris ran our second specialist Sichuan Mammals Tour with a focus on a particularly special species. The trip was run with Martin Royle, Roland Zeidler & Sid Francis as our guides. We visited 3 different locations (covering the rugged bamboo forests of the greater Wolong ecosystem, the high altitude grasslands of Rouergai and the wonderful forests of Tangjiahe. We were very successful with sightings of 44 different species of mammals and over 100 species of birds including Giant Panda, Red Panda, Pallas’s Cat, Chinese Mountain Cat, Indochinese Leopard Cat, Particoloured Flying Squirrel, Golden Snub-nosed Monkey, Chinese Ferret Badger, Eurasian Otter and Chinese Pipistrelle. We ran a second Sichuan’s Mammals Tour (back to back with this one) in April 2019 and we had even more success in some areas. The sightings log for that trip will follow in a few days. We have started to promote our 2020 Sichuan Mammals Tour (with special focus on a particular special species for half of the trip); we have already received many bookings on these two trips. Our first tour for 2020 (9th – 22nd March 2020) has just one place remaining and our second tour for 2020 (25th April – 8th May 2020) which also has only one place remaining. We have also started offering places on another specialist mammal tour of China, visiting Qinghai and the wonderful Valley of the Cats. This tour is for July 2020 (1st – 15th July 2020) and focuses on Snow leopards, Eurasian lynx, Himalayan wolf, Himalayan brown bear, Tibetan antelope, Wild Yak, White-lipped deer, Alpine musk deer, Glover’s pika, Bharal, McNeil’s deer and many more species. -

Reproductive Seasonality in Captive Wild Ruminants: Implications for Biogeographical Adaptation, Photoperiodic Control, and Life History

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Reproductive seasonality in captive wild ruminants: implications for biogeographical adaptation, photoperiodic control, and life history Zerbe, Philipp Abstract: Zur quantitativen Beschreibung der Reproduktionsmuster wurden Daten von 110 Wildwiederkäuer- arten aus Zoos der gemässigten Zone verwendet (dabei wurde die Anzahl Tage, an denen 80% aller Geburten stattfanden, als Geburtenpeak-Breite [BPB] definiert). Diese Muster wurden mit verschiede- nen biologischen Charakteristika verknüpft und mit denen von freilebenden Tieren verglichen. Der Bre- itengrad des natürlichen Verbreitungsgebietes korreliert stark mit dem in Menschenobhut beobachteten BPB. Nur 11% der Spezies wechselten ihr reproduktives Muster zwischen Wildnis und Gefangenschaft, wobei für saisonale Spezies die errechnete Tageslichtlänge zum Zeitpunkt der Konzeption für freilebende und in Menschenobhut gehaltene Populationen gleich war. Reproduktive Saisonalität erklärt zusätzliche Varianzen im Verhältnis von Körpergewicht und Tragzeit, wobei saisonalere Spezies für ihr Körpergewicht eine kürzere Tragzeit aufweisen. Rückschliessend ist festzuhalten, dass Photoperiodik, speziell die abso- lute Tageslichtlänge, genetisch fixierter Auslöser für die Fortpflanzung ist, und dass die Plastizität der Tragzeit unterstützend auf die erfolgreiche Verbreitung der Wiederkäuer in höheren Breitengraden wirkte. A dataset on 110 wild ruminant species kept in captivity in temperate-zone zoos was used to describe their reproductive patterns quantitatively (determining the birth peak breadth BPB as the number of days in which 80% of all births occur); then this pattern was linked to various biological characteristics, and compared with free-ranging animals. Globally, latitude of natural origin highly correlates with BPB observed in captivity, with species being more seasonal originating from higher latitudes. -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment for Wangchuck Centennial Park

CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF WANGCHUCK CENTENNIAL PARK i Author(s) : Phurba Lhendup, Eric Wikramanayake, Sarah Freeman, Nikolai Sindorf, Kinley Gyeltshen and Jessica Forrest. SUPPORT TEAMS WWF Bhutan 1. Vijay Moktan 2. Pema Tshering 3. Dechen Yeshi WWF US 1. Jon Miceler 2. Jeff Price 3. Bart Wickel Wangchuck Centennial Park 1. Damber Singh Rai 2. Tenzin 3. Lekey Dorji 4. Ratna Bdr. Mongar 5. Rinzin Copy Right© photographs: Phurba Lhendup (for those not cited) Design and Layout : Kado Printed at: Norbu Rabten Press, Thimphu. For further information contact Freshwater and climate change program WWF- Bhutan Program Office Post Box No.210, Kawajangsa, Thimphu Tel : +975 3 23316 Fax: +975 3 23518 Email:[email protected] Copyright © WWF & WCP Thimphu, Bhutan August 2011 ii ACKNowLEDGemeNts e would like to convey our appreciation to all contributing teams from Wangchuck Centennial Park, WWF US and WWF Bhutan for their Wdedication and effort which has led to this research report. We would also like to thank the reviewers from WWF US office (Judy Ogelthorpe, Jon Miceler, Bart Wickel, June Reyes, Eliot Levine, Shubash Lohani) for their comments and constructive inputs. The suggestions made by Jonathan Cook and John Mathews during the time of proposal development are also appreciated. This initiative is a part of program funded by WWF Finland, WWF US and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Finland for enabling biodiversity conservation in the Wangchuck Centennial Park. The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge their generosity. Finally, our appreciation and heartfelt gratitude also go to all the members of local communities from Chhokhor, Tang, Nubi and Sephu geogs and officials who provided necessary information during the time of our research in the field. -

Cervid Mixed-Species Table That Was Included in the 2014 Cervid RC

Appendix III. Cervid Mixed Species Attempts (Successful) Species Birds Ungulates Small Mammals Alces alces Trumpeter Swans Moose Axis axis Saurus Crane, Stanley Crane, Turkey, Sandhill Crane Sambar, Nilgai, Mouflon, Indian Rhino, Przewalski Horse, Sable, Gemsbok, Addax, Fallow Deer, Waterbuck, Persian Spotted Deer Goitered Gazelle, Reeves Muntjac, Blackbuck, Whitetailed deer Axis calamianensis Pronghorn, Bighorned Sheep Calamian Deer Axis kuhili Kuhl’s or Bawean Deer Axis porcinus Saurus Crane Sika, Sambar, Pere David's Deer, Wisent, Waterbuffalo, Muntjac Hog Deer Capreolus capreolus Western Roe Deer Cervus albirostris Urial, Markhor, Fallow Deer, MacNeil's Deer, Barbary Deer, Bactrian Wapiti, Wisent, Banteng, Sambar, Pere White-lipped Deer David's Deer, Sika Cervus alfredi Philipine Spotted Deer Cervus duvauceli Saurus Crane Mouflon, Goitered Gazelle, Axis Deer, Indian Rhino, Indian Muntjac, Sika, Nilgai, Sambar Barasingha Cervus elaphus Turkey, Roadrunner Sand Gazelle, Fallow Deer, White-lipped Deer, Axis Deer, Sika, Scimitar-horned Oryx, Addra Gazelle, Ankole, Red Deer or Elk Dromedary Camel, Bison, Pronghorn, Giraffe, Grant's Zebra, Wildebeest, Addax, Blesbok, Bontebok Cervus eldii Urial, Markhor, Sambar, Sika, Wisent, Waterbuffalo Burmese Brow-antlered Deer Cervus nippon Saurus Crane, Pheasant Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Hog Deer, Sambar, Barasingha, Nilgai, Wisent, Pere David's Deer Sika 52 Cervus unicolor Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Barasingha, Nilgai, Rusa, Sika, Indian Rhino Sambar Dama dama Rhea Llama, Tapirs European Fallow Deer -

Sichuan Takin... a Bizarre and Fantastic Beast!

CAPRINAE TAG Sichuan takin ... a bizarre and fantastic beast! Why exhibit Sichuan takin? • Ignite the curiosity of your guests with these large and bizarre-looking ungulates that look like a cross between a bison, a bear, and a wildebeest! • Piggyback on the popularity of giant pandas even in the absence of the black-and-white bears. Takin and pandas share the same habitat, face similar threats, and benefit from the same habitat conservation projects. • Create memorable guest encounters with these confident caprids, using a training wall for feeding or to show off their impressive hind-leg stand. • Present a spectacular cold-weather exhibit with these active and hardy animals. Their distinctive bulbous noses help warm inhaled air, providing a great interpretive opportunity. • Enchant guests with frisky, teddy-bear-like kids and boost social media hits by posting videos of their antics! MEASUREMENTS IUCN Length: 5.5-7.5 feet VULNERABLE Height: 3.5-4.5 feet CITES II Stewardship Opportunities at shoulder Takin monitoring in Tangjiahe Nature Reserve Weight: 330-750 lbs Unknown # http://conservationcenters.org/conservation-research/sichuan-takin Montane forest China in the wild Care and Husbandry YELLOW SSP: 69.54.2 (125) 17 AZA (+5 non-AZA) institutions (2015) Species coordinator: Dave Bernier, Lincoln Park Zoo [email protected] ; (312)742-0539 Social nature: Social, with a distinct dominance hierarchy. Can be held in very large herds with sufficient space, although one male with several females is most common. Mixed species: Successfully mixed with a variety of smaller hoofstock, including muntjac, goral, wild sheep, and blackbuck. Housing: A hardy, cold-tolerant species. -

Ungulate Tag Marketing Profiles

AZA Ungulates Marketing Update 2016 AZA Midyear Meeting, Omaha NE RoxAnna Breitigan -The Living Desert Michelle Hatwood - Audubon Species Survival Center Brent Huffman -Toronto Zoo Many hooves, one herd COMMUNICATION Come to TAG meetings! BUT it's not enough just to come to the meetings Consider participating! AZAUngulates.org Presentations from 2014-present Details on upcoming events Husbandry manuals Mixed-species survey results Species profiles AZAUngulates.org Content needed! TAG pages Update meetings/workshops Other resources? [email protected] AZAUngulates.org DOUBLE last year’s visits! Join our AZA Listserv [AZAUngulates] Joint Ungulate TAG Listserv [email protected] To manage your subscription: http://lists.aza.org/cgi-bin/mailman/listinfo/azaungulates Thanks to Adam Felts (Columbus Zoo) for moderating! Find us on Facebook www.facebook.com/AZAUngulates/ 1,402 followers! Thanks to Matt Ardaiolo (Denver Zoo) for coordinating! Joining forces with IHAA International Hoofstock Awareness Association internationalhoofstock.org facebook.com INITIATIVES AZA SAFE (Saving Animals From Extinction) AZA initiative Launched in 2015 Out of 144 nominations received, 24 (17%) came from the Ungulate TAGs (all six TAGs had species nominated). Thank you to everyone who helped!!! Marketing Profiles •Audience: decision makers •Focus institutional interest •Stop declining trend in captive ungulate populations •63 species profiles now available online Marketing Profiles NEW for this year! Antelope & Giraffe TAG Caprinae TAG Black