Upton Sinclair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Ellen Glasgow's in This Our Life

69 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2019-0016 American, British and Canadian Studies, Volume 33, December 2019 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life: “The Betrayals of Life” in the Crumbling Aristocratic South IULIA ANDREEA MILICĂ Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Romania Abstract Ellen Glasgow’s works have received, over time, a mixed interpretation, from sentimental and conventional, to rebellious and insightful. Her novel In This Our Life (1941) allows the reader to have a glimpse of the early twentieth-century South, changed by the industrial revolution, desperately clinging to dead codes, despairing and struggling to survive. The South is reflected through the problems of a family, its sentimentality and vulnerability, but also its cruelty, pretensions, masks and selfishness, trying to find happiness and meaning in a world of traditions and codes that seem powerless in the face of progress. The novel, apparently simple and reduced in scope, offers, in fact, a deep insight into various issues, from complicated family relationships, gender pressures, racial inequality to psychological dilemmas, frustration or utter despair. The article’s aim is to depict, through this novel, one facet of the American South, the “aristocratic” South of belles and cavaliers, an illusory representation indeed, but so deeply rooted in the world’s imagination. Ellen Glasgow is one of the best choices in this direction: an aristocratic woman but also a keen and profound writer, and, most of all, a writer who loved the South deeply, even if she exposed its flaws. Keywords : the South, aristocracy, cavalier, patriarchy, southern belle, women, race, illness The American South is an entity recognizable in the world imagination due to its various representations in fiction, movies, politics, entertainment, advertisements, etc.: white-columned houses, fields of cotton, belles and cavaliers served by benevolent slaves, or, on the contrary, poverty, violence and lynching. -

Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2014 Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R. Moquin St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Katelin R., "Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground" (2014). Culminating Projects in English. 2. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND by Katelin Ruth Moquin B.A., Concordia University – Ann Arbor, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree: Master of Arts St. Cloud, Minnesota December, 2014 Moquin 2 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND Katelin Ruth Moquin Through a Cultural Studies lens and with Formalist-inspired analysis, this thesis paper addresses the complexly interwoven elements of land, body, and fate in Ellen Glasgow’s Barren Ground . The introductory chapter is a survey of the critical attention, and lack thereof, Glasgow has received from various literary frameworks. Chapter II summarizes the historical foundations of the South into which Glasgow’s fictionalized South is rooted. -

Humanities 1

Humanities 1 Humanities HUM 1100. Philosophy: Good Questions for Life. 2 Units. HUM 1100A. Studies in Humanities: The Classical Word. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1110. Literature: Reading Cultures. 2 Units. HUM 1110A. Studies in the Humanities: Renaissance To Enlightenment. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1120. Art History: Visual Literacy. 2 Units. HUM 1120A. Studies in the Humanities: Contemporary Voices. 2-3 Unit. HUM 1510. Independent Study: Humanities. 1-5 Unit. HUM 2500. Prior Learning: Humanities. 1-5 Unit. HUM 3030. Twenty-First Century Latin American Social Movements. 3-4 Unit. HUM 3040. Birds in the Field & Human Imagination. 3-4 Unit. The purpose of this course is to engage a tradition that spans millennia and every culture: a human fascination with birds. Taking a multidisciplinary approach, we will explore birds through many lens and avenues. As naturalists, we will seek out birds in the wild, experimenting with different approaches to observation. We will consider common themes in the life circumstances of birds, as well as explore the impact of human civilization on the ecology of natural habitats. Further, we will explore birds as symbols of the human imagination as expressed. HUM 3070. Borderlands: Exploring Identities & Borders. 3-4 Unit. HUM 3090. Queer Perspectives: Applications in Contemporary Soc. 3-4 Unit. This course critically addresses the term ?queer,? its changing definition, and the particular ways in which it has described, marginalized and excluded people, communities and modes of thought. Using both academic and empirical examples, students will explore and uncover how queer thought has influenced such diverse human endeavors as civil rights, athletics, literature, pop culture, and science. -

"The America We Lost." the Saturday Evening Post. May 31, 1952

Pei, Mario A. "The America We Lost." The Saturday Evening Post. May 31, 1952. American Coalition Resolutions. "Federal Aid to Education." Turner, Fred. "How a Housewife Routed the Reds." The American Legion Magazine. November 1951. Sargent, Aaron M. "Looking at the Foundations." February 8, 1955 meeting of San Mateo County Council of Republican Women. "Petition to the United States Congress to Impeach Dean Acheson for Conspiracy Against the United States." May 1949. Constitutional Educational League release of March 6, 1950 "America Betrayed." Budenz, Louis Francis. "How the Reds Invaded Radio." The American Legion Magazine. December 1950. Budenz, Louis Francis. "Do Colleges Have to Hire Red Professors?" The American Legion Magazine. November 1951. La Varre, William. "Moscow's Red Letter Day in American History." The American Legion Magazine. August 1951. Lyons, Eugene. "Our New Privileged Class." The American Legion Magazine. September 1951. Utley, Freda. "The Strange Case of the I.P.R." The American Legion Magazine. March 1952. Baarslag, Karl. "What Have We Bought." The American Legion Magazine. April 1953. Hurston, Zora Neale. "Why the Negro Won't Buy Communism." The American Legion Magazine. June 1951. Kuhn, Irene Corbally. "Why You Buy Books That Sell Communism." The American Legion Magazine. January 1951. Kuhn, Irene Corbally. "Your Child is Their Target." The American Legion Magazine. June 1952. Gern, Gregory G., ed. "Annual Report to Republicans." 1951-52. Gutstadt, Richard E., Director of Anti-Defamation League. Letter to the Publishers of Anglo-Jewish Periodicals. December 13, 1933. Bentley, Elizabeth Terrill. Digest of Testimony. Donner, Robert. Letter to Trustees of Bennett Junior College. May 3, 1952. -

The Counterculture of the 1960S in the United States: an ”Alternative Consciousness”? Mélisa Kidari

The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An ”Alternative Consciousness”? Mélisa Kidari To cite this version: Mélisa Kidari. The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An ”Alternative Conscious- ness”?. Literature. 2012. dumas-00930240 HAL Id: dumas-00930240 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00930240 Submitted on 14 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An "Alternative Consciousness"? Nom : KIDARI Prénom : Mélisa UFR ETUDES ANGLOPHONES Mémoire de master 1 professionnel - 12 crédits Spécialité ou Parcours : parcours PLC Sous la direction de Andrew CORNELL Année universitaire 2011-2012 The Counterculture of the 1960s in the United States: An "Alternative Consciousness"? Nom : KIDARI Prénom : Mélisa UFR ETUDES ANGLOPHONES Mémoire de master 1 professionnel - 12 crédits Spécialité ou Parcours : parcours PLC Sous la direction de Andrew CORNELL Année universitaire 2011-2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Mr. Andrew Cornell for his precious advice and his -

Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-24-2012 Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sneider, Jill, "Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 728. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/728 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: Wayne Fields, Chair Naomi Lebowitz Robert Milder George Pepe Richard Ruland Lynne Tatlock Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories By Jill Frank Sneider A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright by Jill Frank Sneider 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Washington University and the Department of English and American Literature for their flexibility during my graduate education. Their approval of my part-time program made it possible for me to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. I appreciate the time, advice, and encouragement given to me by Wayne Fields, the Director of my dissertation. He helped me discover new facets to explore every time we met and challenged me to analyze and write far beyond my own expectations. -

National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works English and Technical Communication 01 Jan 2005 Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933 Kathleen Morgan Drowne Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/eng_teccom_facwork Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Drowne, Kathleen. "Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933." Columbus, Ohio, The Ohio State University Press, 2005. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page i SPIRITS OF DEFIANCE Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iii Spirits of Defiance NATIONAL PROHIBITION AND JAZZ AGE LITERATURE, 1920–1933 Kathleen Drowne The Ohio State University Press Columbus Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iv Copyright © 2005 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drowne, Kathleen Morgan. Spirits of defiance : national prohibition and jazz age literature, 1920–1933 / Kathleen Drowne. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–8142–0997–1 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0–8142–5142–0 (pbk. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

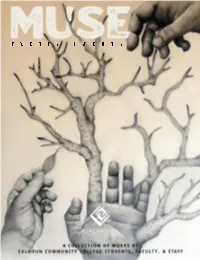

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication.