Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellen Glasgow's in This Our Life

69 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2019-0016 American, British and Canadian Studies, Volume 33, December 2019 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life: “The Betrayals of Life” in the Crumbling Aristocratic South IULIA ANDREEA MILICĂ Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Romania Abstract Ellen Glasgow’s works have received, over time, a mixed interpretation, from sentimental and conventional, to rebellious and insightful. Her novel In This Our Life (1941) allows the reader to have a glimpse of the early twentieth-century South, changed by the industrial revolution, desperately clinging to dead codes, despairing and struggling to survive. The South is reflected through the problems of a family, its sentimentality and vulnerability, but also its cruelty, pretensions, masks and selfishness, trying to find happiness and meaning in a world of traditions and codes that seem powerless in the face of progress. The novel, apparently simple and reduced in scope, offers, in fact, a deep insight into various issues, from complicated family relationships, gender pressures, racial inequality to psychological dilemmas, frustration or utter despair. The article’s aim is to depict, through this novel, one facet of the American South, the “aristocratic” South of belles and cavaliers, an illusory representation indeed, but so deeply rooted in the world’s imagination. Ellen Glasgow is one of the best choices in this direction: an aristocratic woman but also a keen and profound writer, and, most of all, a writer who loved the South deeply, even if she exposed its flaws. Keywords : the South, aristocracy, cavalier, patriarchy, southern belle, women, race, illness The American South is an entity recognizable in the world imagination due to its various representations in fiction, movies, politics, entertainment, advertisements, etc.: white-columned houses, fields of cotton, belles and cavaliers served by benevolent slaves, or, on the contrary, poverty, violence and lynching. -

Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2014 Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R. Moquin St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Katelin R., "Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground" (2014). Culminating Projects in English. 2. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND by Katelin Ruth Moquin B.A., Concordia University – Ann Arbor, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree: Master of Arts St. Cloud, Minnesota December, 2014 Moquin 2 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND Katelin Ruth Moquin Through a Cultural Studies lens and with Formalist-inspired analysis, this thesis paper addresses the complexly interwoven elements of land, body, and fate in Ellen Glasgow’s Barren Ground . The introductory chapter is a survey of the critical attention, and lack thereof, Glasgow has received from various literary frameworks. Chapter II summarizes the historical foundations of the South into which Glasgow’s fictionalized South is rooted. -

Proverbs 11:1 May 20, 2020 Pare

1 “A false balance is an abomination to the Lord, but a just weight is his delight.” - - Proverbs 11:1 May 20, 2020 Parents and Students, Because the administration has directed that no official project or writing assignment be attached to summer reading, I am not changing it much from what I had last year for Honors and AP students.. Honestly, if your student is reading anything and enjoying it, that’s great! The connection between reading and academic success -- both now and on standardized tests, writing, and post secondary learning -- is overwhelming! I recommend (and this is advice I have to take myself!) branching out from one’s favorite genre for variety and to discover additional types of writing to enjoy. Other than recommendations from people you know who have studied or read the works, an easy option for choosing a book is to look up an excerpt of the novel/drama. That way, you know the level of difficulty as well as the author’s style and language. Almost all good literature contains less-than-savory elements -- language, sinful behavior, sometimes even an overt or subtle skewed world view. With that disclaimer comes the fact that most, if not all good literature that I have read doesn’t glorify sin but punishes it in some way. Christian family review sites also exist, including the following: Redeemed Reader, Focus on the Family, Plugged In, and Common Sense Media. Below is a lengthy article by Bob Jones University that deals with potentially objectionable material from a biblical worldview in a thorough manner. -

Pleasure and Reality in Edith Wharton's the Fulness Of

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 PLEASURE AND REALITY IN EDITH WHARTON’S THE FULNESS OF LIFE Mr. V. R. YASU BHARATHI, Ph.D Research Scholar (Full-Time), P.G & Research Department of English, V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi – 628008. Affiliated to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli Dr. V. CHANTHIRAMATHI, Research Guide, P.G & Research Department of English, V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi – 628008 Affiliated to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli ABSTRACT: This paper focuses on the psychological aspects in the short story of Edith Wharton’s The Fulness of Life. The revelation of the unnamed lifeless woman about her past life to her own spirit is the plot of The Fulness of Life. This paper analyses how the author’s Id, Sigmund Freud’s pleasure principle, is revealed through the protagonist of the story. This paper attempts to explore the pleasures expected by the unnamed lady and the reality she had to face. This paper follows MLA Eighth Edition for Research Methodology. Key Words- Edith Wharton, Short-Story, Freud’s Psychology, id and ego, expectation and reality. ----------------------------- Literature is considered as reflection of life. It also speaks about many segments and dimensions found among human being. The writer, work background and the purpose of work are to be known to analyze each and every character and circumstances found in the works. Psychology is one such background interrelated by the authors to achieve their intense purpose of writing. In literature there are many forms of writing, classified mainly as poetry, drama and prose. Short story, in this classification, comes under prose. -

Pós-Graduação Em Letras-Inglês Social Critique in Scorsese's the Age of Innocence and Madden's Ethan Frome: Filmic Adaptat

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS-INGLÊS SOCIAL CRITIQUE IN SCORSESE'S THE AGE OF INNOCENCE AND MADDEN'S ETHAN FROME: FILMIC ADAPTATIONS OF TWO NOVELS BY EDITH WHARTON por HELEN MARIA LINDEN Dissertação submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS Novembro, 1996 Esta Dissertação foi julgada adequada e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS Opção Literatura Jos Roberto O'Shea OORDENÀDOR Anelise Reich Corseuil ORIENTADORA BANCA EXAMINADORA: Anelise Reich Corseuil Bernadete Pasold Florianópolis, 28 de novembro de 1996. Ill ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM INGLÊS of the UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA, in special Dr. Anelise Reich Corseuil, my advisor, for the academic support and friendship. Besides the professors that have, in one way or another, enabled me to write this dissertation. Dr. Bernadete Pasold deserves special thanks for her interest in reading and discussing specific parts of my study. Dr. Sara Kozloff, from Vassar College, also devoted some time in reading part of my dissertation and providing interesting suggestions. I am grateful for her interest and contribuitions. I could not exclude Professor John Caughie, from Glasgow University, whose important insights for my research were given during his stay in Florianópolis. I would also like to thank CNPq for the financial support which enabled me to develop this research. I am very grateful to my friend and colleague Viviane Heberle whose invitation to enter the program was the starting point of my return to the academic life. -

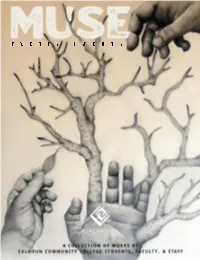

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

1 CRIES and WHISPERS Jean Morris Is a Spanish / French

CRIES AND WHISPERS Jean Morris is a Spanish / French / English translator living in London. She has been collaborating with me since 2015 translating into English the subtitles for most of the poems I choose for my videos. She is an extraordinary and generous professional, and also an amazing poet, sensitive and technically accurate. Cries and Whispers is not the first poem of hers that I have worked with: Domingo después del vendaval (Sunday Morning After Gales), Shelter (an unfinished project) and, of course, Metamorphosis, a happy collaboration made under the direction of filmmaker Marie Craven. As usual, Jean gave me total freedom to work with her poem as I liked. I asked her to explain a little more about the period the poem is set in. She told me that she wrote the poem from her experience spending some time as a student of Spanish in Granada in 1975. What happens in the poem is Jean’s real life; she is able to write good poetry from her own life, so moving and profound. The way she mixes her father's death with the Ingmar Bergman film Cries and Whispers (Gritos y Susurros, or Viskningar och Rop) (1972) astonished me. Then I had the idea of linking her father's death to the historical death that occurred that year of 1975 in Spain and changed the country: Fascist dictator Franco's death (a disgusting and extremely tough “father”, by the way). The weird mix of footages and sounds gave me the idea of the introductory sentence of the video: A film found in a hard disk drive (or the modern place where we store our memories). -

THE JUNGLE by VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF UPTON SINCLAIR’S THE JUNGLE By VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle 2 INTRODUCTION The Jungle by Upton Sinclair was written at the turn of the twentieth century. This period is often painted as one of advancement of the human condition. Sinclair refutes this by unveiling the horrible injustices of Chicago’s meat packing industry as Jurgis Rudkus, his protagonist, discovers the truth about opportunity and prosperity in America. This book is a good choice for eleventh and twelfth grade, junior college, or college students mature enough to understand the purpose of its content. The “hooks” for most students are the human-interest storyline and the graphic descriptions of the meat industry and the realities of immigrant life in America. The teacher’s main role while reading this book with students is to help them understand Sinclair’s purpose. Coordinating the reading of The Jungle with a United States history study of the beginning of the 1900s will illustrate that this novel was not intended as mere entertainment but written in the cause of social reform. As students read, they should be encouraged to develop and express their own ideas about the many political, ethical, and personal issues addressed by Sinclair. This guide includes an overview, which identifies the main characters and summarizes each chapter. -

The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information The Films of Ingmar Bergman This volume provides a concise overview of the career of one of the modern masters of world cinema. Jesse Kalin defines Bergman’s conception of the human condition as a struggle to find meaning in life as it is played out. For Bergman, meaning is achieved independently of any moral absolute and is the result of a process of self-examination. Six existential themes are explored repeatedly in Bergman’s films: judgment, abandonment, suffering, shame, a visionary picture, and above all, turning toward or away from others. Kalin examines how Bergman develops these themes cinematically, through close analysis of eight films: well-known favorites such as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, and Fanny and Alexander; and im- portant but lesser-known works, such as Naked Night, Shame, Cries and Whispers, and Scenes from a Marriage. Jesse Kalin is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities and Professor of Philosophy at Vassar College, where he has taught since 1971. He served as the Associate Editor of the journal Philosophy and Literature, and has con- tributed to journals such as Ethics, American Philosophical Quarterly, and Philosophical Studies. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE FILM CLASSICS General Editor: Ray Carney, Boston University The Cambridge Film Classics series provides a forum for revisionist studies of the classic works of the cinematic canon from the perspective of the “new auterism,” which recognizes that films emerge from a complex interaction of bureaucratic, technological, intellectual, cultural, and personal forces. -

REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 Winter 2018 My Ántonia at 100 Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 | Winter 2018 28 35 2 15 22 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director, the President 20 Reading My Ántonia Gave My Life a New Roadmap and the Editor Nancy Selvaggio Picchi 2 Sharing Ántonia: A Granddaughter’s Purpose 22 My Grandmother—My Ántonia z Kent Pavelka Tracy Sanford Tucker z Daryl W. Palmer 23 Growing Up with My Ántonia z Fritz Mountford 10 Nebraska, France, Bohemia: “What a Little Circle Man’s My Ántonia, My Grandparents, and Me z Ashley Nolan Olson Experience Is” z Stéphanie Durrans 24 24 Reflection onMy Ántonia z Ann M. Ryan 10 Walking into My Ántonia . z Betty Kort 25 Red Cloud, Then and Now z Amy Springer 11 Talking Ántonia z Marilee Lindemann 26 Libby Larsen’s My Ántonia (2000) z Jane Dressler 12 Farms and Wilderness . and Family z Aisling McDermott 27 How I Met Willa Cather and Her My Ántonia z Petr Just 13 Cather in the Classroom z William Anderson 28 An Immigrant on Immigrants z Richard Norton Smith 14 Each Time, Something New to Love z Trish Schreiber 29 My Two Ántonias z Evelyn Funda 14 Our Reflections onMy Ántonia: A Family Perspective John Cather Ickis z Margaret Ickis Fernbacher 30 Pioneer Days in Webster County z Priscilla Hollingshead 15 Looking Back at My Ántonia z Sharon O’Brien 31 Growing Up in the World of Willa Cather z Kay Hunter Stahly 16 My Ántonia and the Power of Place z Jarrod McCartney 32 “Selah” z Kirsten Frazelle 17 My Ántonia, the Scholarly Edition, and Me z Kari A. -

Minor Storm Causes Slippery Travel

(Eatm?rttntt Sathj dampus Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXIX NO. 60 STORRS. CONNECTICUT WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 21, 1976 K urn i This parking lol served as a harbor for cars while the campus maintainence crews worked to clear the roads following yesterdays minor snowstorm. Minor storm causes slippery travel By MARK A. DUPUIS campus roads throughout the afternoon >anding sidewalks throughout the day. accidents not to slippery sidewalks, but News Editor as motorists moved away from the said M. Frank Laudieri. physical plant students and staff taking shortcuts across Students slipped and slid around University at a crawl. director. unsanded grass areas. campus Tuesday as a minor snowstorm Campus police and fire officials report- Laudieri said sanding began early Federation of Students and Service dumped several inches of white cover ed several persons had sustained minor Tuesday morning with plowing com- Organizations Chairman Robert C. onto already covered ley walks and roads injuries from sipping and falling while pleted by mid-afternoon. Laudieri said Woodard labeled the icy conditions as with several inches of white powder. walking on the ice. A spokesmman for the most of the sanding would be completed "atrocious." attributing the icy walks to By early evening. Physical Plant and University Fire Department (UCFD) said by early Tuesday evening and students budget cutbacks at the Physical Plant. state highway department crews had at least two persons had been transported would be greeted by safer walkways as "It's my feeling that public safety is moved onto campus to plow and sand to the Infirmary by ambulance for they walked towards classes today. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,