Attitudes of the Major Soviet Nationalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Audience Development in Latvia (2004–2012)

ISSN 2029-865X 144 doi://10.7220/2029-865X.06.06 MEDIA AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT IN LATVIA (2004–2012) Anda ROŽUKALNE [email protected] PhD, Head of the Department of Communication Studies Faculty of Communication Riga Stradiņš University Riga, Latvia ABSTRACT: This article analyses the main development trends in media audience structure and media use in Latvia since its joining the European Union in 2004. To characterize and carry out the analysis quantitative data were mainly used which are regularly provided by TNS Latvia – an agency for market, social and media research. In addition to the information provided by TNS Latvia, this summary also employs a study on broadcasting media audience structure and content priorities commissioned by the National Electronic Media Council and carried out by the Baltic Institute of Social Sciences. In order to describe media usage patterns in different au- dience groups, data from polls and focus group studies were used, carried out by the author. The behavior of media audience is characterized by taking into account media consumption and providing detailed information about press, broadcasting and Internet media usage trends. The data show that Latvian media consumption time and the diversity in media usage is increasing. Due to technological development, some audiences tend to consume less of traditional media, giving preference to Internet media where it is possible to receive all the necessary information. National social networking site draugiem.lv has become increasingly popular in the local media environment, where people are mainly communicating among themselves. Latvian media audi- ence can also be described by a generational gap – people below thirty mainly use Internet media, while those above 30 tend, in their use, to combine both traditional and Internet media. -

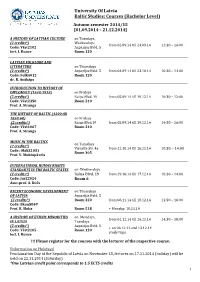

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Bachelor Theses 1996 - 2020

Bachelor Theses 1996 - 2020 ID Title Name Surname Year Supervisor Pages Notes Year 2020 Are individual stock prices more efficient than Jānis Beikmanis 2020 SSE Riga Student Research market-wide prices? Evidence on the evolution of 2020 Tālis Putniņš 49 01 Papers 2020 : 3 (225) Samuelson’s Dictum Pauls Sīlis 2020 Assessment of the Current Practices in the Justs Patmalnieks 2020 Viesturs Sosars 50 02 Magnetic Latvia Business Incubator Programs Kristaps Volks 2020 Banking business model development in Latvia Janis Cirulis 2020 Dmitrijs Kravceno 36 03 between 2014 and 2018 2020 Betting Markets and Market Efficiency: Evidence Laurynas Janusonis 2020 Tarass Buka 55 04 from Latvian Higher Football League Andrius Radiul 2020 Building a Roadmap for Candidate Experience in Jelizaveta Lebedeva 2020 Inga Gleizdane 53 05 the Recruitment Process Madara Osīte Company financial performance after receiving Ernests Pulks 2020 non-banking financing: Evidence from the Baltic 2020 Anete Pajuste 44 06 market Patriks Simsons Emīls Saulītis 2020 Consumer behavior change due to the emergence 2020 Aivars Timofejevs 41 07 of the free-floating car-sharing services in Riga Vitolds Škutāns 2020 Content Marketing in Latvian Tech Startups Dana Zueva 2020 Aivars Timofejevs 64 08 Corporate Social Responsibility: An Analysis of Laura Ramza 2020 Companies’ CSR Activities Relationship with Their 2020 Anete Pajuste 48 09 Financial Performance in the Baltic States Santa Usenko 2020 Determinants of default probabilities: Evidence Illia Hryzhenku 2020 Kārlis Vilerts 40 10 from -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 30.9.2020 SWD(2020) 313 Final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT 2020 Rule of Law Report Country C

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 30.9.2020 SWD(2020) 313 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT 2020 Rule of Law Report Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Latvia Accompanying the document COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS 2020 Rule of Law Report The rule of law situation in the European Union {COM(2020) 580 final} - {SWD(2020) 300 final} - {SWD(2020) 301 final} - {SWD(2020) 302 final} - {SWD(2020) 303 final} - {SWD(2020) 304 final} - {SWD(2020) 305 final} - {SWD(2020) 306 final} - {SWD(2020) 307 final} - {SWD(2020) 308 final} - {SWD(2020) 309 final} - {SWD(2020) 310 final} - {SWD(2020) 311 final} - {SWD(2020) 312 final} - {SWD(2020) 314 final} - {SWD(2020) 315 final} - {SWD(2020) 316 final} - {SWD(2020) 317 final} - {SWD(2020) 318 final} - {SWD(2020) 319 final} - {SWD(2020) 320 final} - {SWD(2020) 321 final} - {SWD(2020) 322 final} - {SWD(2020) 323 final} - {SWD(2020) 324 final} - {SWD(2020) 325 final} - {SWD(2020) 326 final} EN EN ABSTRACT The Latvian justice system has been continuously improving its quality and efficiency, notably through a number of measures, among them training and consecutive judicial map reforms. The Information and Communication System in courts and the Prosecution Office is at an advanced level and is being further developed. The independence of the justice system has been strengthened by reinforcing the role of the judiciary in the selection of candidate judges and the Prosecutor General, as well as in the appointment of court presidents. -

Latviešu-Lībiešu-Angļu Sarunvārdnīca Leţkīel-Līvõkīel-Engliškīel Rõksõnārōntõz Latvian-Livonian-English Phrase Book

Valda Šuvcāne Ieva Ernštreite Latviešu-lībiešu-angļu sarunvārdnīca Leţkīel-līvõkīel-engliškīel rõksõnārōntõz Latvian-Livonian-English Phrase Book © Valda Šuvcāne 1999 © Ieva Ernštreite 1999 © Eraksti 2005 ISBN-9984-771-74-1 68 lpp. / ~ 0.36 MB SATURS SIŽALI CONTENTS I. IEVADS ĪEVAD INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ I.1. PRIEKŠVĀRDS 5 EĆĆISÕNĀ 6 FOREWORD 6 I.2. LĪBIEŠI, VIŅU VALODA UN RAKSTĪBA 7 LĪVLIST, NÄNT KĒĻ JA KĒRAVĪŢ LIVONIANS, THEIR LANGUAGE AND ORTOGRAPHY 12 I.3. NELIELS IESKATS LĪBIEŠU VALODAS GRAMATIKĀ 9 LĪTÕ IĻ LĪVÕ GRAMĀTIK EXPLANATORY NOTES ON THE MAIN FEATURES OF THE LIVONIAN SPELLING AND PRONUNCIATION 14 _____________________________________________________________________________ II. BIEŽĀK LIETOTĀS FRĀZES SAGGÕLD KȬLBATÕT FRĀZÕD COMMON USED PHRASES __________________________________________________________________ II.1. SASVEICINĀŠANĀS UN ATVADĪŠANĀS 16 TĒRIŅTÕMI JA JUMĀLÕKS JETĀMI GREETINGS II.2. IEPAZĪŠANĀS UN CIEMOŠANĀS 16 TUNDIMI JA KILĀSTIMI INTRODUCING PEOPLE, VISITING PEOPLE II.3. BIOGRĀFIJAS ZIŅAS 17 BIOGRĀFIJ TEUTÕD PERSON'S BIOGRAPHY II.4. PATEICĪBAS, LĪDZJŪTĪBAS UN PIEKLĀJĪBAS IZTEICIENI 18 TIENĀNDÕKST, ĪŅÕZTŪNDIMI JA ANDÕKS ĀNDAMI SÕNĀD EXPRESSING GRATITUDE, POLITE PHRASES II.5. LŪGUMS 19 PÕLAMI REQUEST II.6. APSVEIKUMI, NOVĒLĒJUMI 19 2 VȮNTARMÕMI CONGRATULATIONS, WISHES II.7. DIENAS, MĒNEŠI, GADALAIKI 20 PǞVAD, KŪD, ĀIGASTĀIGAD WEEKDAYS, MONTHS, SEASONS II.8. LAIKA APSTĀKĻI 23 ĀIGA WEATHER II.9. PULKSTENIS 24 KĪELA TIME, TELLING THE TIME _____________________________________________________________________________ III. VĀRDU KRĀJUMS SÕNA VŌLA VOCABULARY __________________________________________________________________ III.1. CILVĒKS 25 RIŠTĪNG PERSON III.2. ĢIMENE 27 AIM FAMILY III.3. MĀJOKLIS 28 KUOD HOME III.4. MĀJLIETAS, APĢĒRBS 29 KUODAŽĀD, ŌRÕND HOUSEHOLD THINGS, CLOTHING III.5. ĒDIENI, DZĒRIENI 31 SĪEMNAIGĀD, JŪOMNAIGĀD MEALS, FOOD, DRINKS III.6. JŪRA, UPE, EZERS 32 MER, JOUG, JŌRA SEA, LAKE, RIVER III.7. -

Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them?

SSE Riga Student Research Papers 2021 : 2 (234) SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS: WHY DO MANY LATVIAN POLITICIANS RESIST THEM? Authors: Daniela Gerda Baranova Samanta Mežmale ISSN 1691-4643 ISBN 978-9984-822-58-7 May 2021 Riga Same-Sex Relationships: Why Do Many Latvian Politicians Resist Them? Daniela Gerda Baranova and Samanta Mežmale Supervisor: Xavier Landes May 2021 Riga Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Literature Review .................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. LGBT in the World ......................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1. LGBT Movement ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. Legislation ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.3. Sexual orientation discrimination and homophobia ................................................. 11 2.1.4. Supporting organisations ......................................................................................... -

The Role of National Language Policy Institutions in the Implementation of the Law on the Official State Language in Latvia

Ina Druviete/Jānis Valdmanis The role of national language policy institutions in the implementation of the law on the Official State Language in Latvia Abstract (Latvian): Valsts valodas politikas institūciju loma Latvijas Valsts valodas likuma īstenošanā 2018. gada 18. novembrī apritēs simt gadu kopš Latvijas Republikas dibināšanas, un šajā gadā īpaši tiek izvērtēta valsts vēsture un valsts simbolu loma. Latviešu valoda ir galvenais, kaut ne vienīgais, Latvijas nacionālās identitātes elements, tāpēc, 1991. gadā atjaunojot neatkarību pēc padomju okupācijas, latviešu valodas statusa nostiprināšanai un valodas attīstīšanai tika pievērsta īpaša uzmanība. Valsts valodas statuss latviešu valodai tika atjau- nots jau 1988. gadā, paredzot arī īpašu pasākumu kompleksu latviešu valodas apguvei un valodas funkciju atjaunošanai pēc intensīvas rusifikācijas un asimetriskā bilingvisma perioda. 1992. gadā, kad tika veikti grozījumi 1989. gada Valodu likumā, tika likts pamats izvērstajai valsts valodas politikas institūciju sistēmai, pamatojoties uz vispusīgu Latvijas valodas situācijas analīzi, ņemot vērā Latvijas Republikas pieredzi no 1918. gada līdz 1940. gadam un apzinot citu valstu valodas politiku. Pašlaik spēkā ir 1999. gadā pieņemtais Valsts valodas likums, kura izpildi konkretizē vairāki Ministru Kabineta noteikumi, kā arī valdības apstiprinātas Valsts valodas politikas programmas (2010-2014, 2015-2020). Raksturīga Latvijas valodas politikas īpatnība no neatkarības atjaunošanas līdz pat mūsu dienām ir profesionālu sociolingvistu iesaiste lingvistiskajā -

Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1

No 6 FORUM FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURE 144 Svetlana Ryzhakova Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1 In fond memory of my teacher, Vladimir Nikolaevich Toporov The term svēts, meaning ‘holy, sacred’ and its derivatives svētums (‘holiness’, ‘shrine/sacred place’), svētība (‘blessing’, ‘paradise’), svētlaime (‘bliss’), svētīt (‘to bless’, ‘to celebrate’), and svētīgs (‘blessed’, ‘sacred’) comprise an im- portant lexical and semantic field in the Latvian language. These lexemes are regularly en- countered in even the earliest Latvian texts, beginning in the 16th century,2 and are no less frequent in Baltic hydronomy and toponymy, as well as in folklore and colloquial speech. According to fairly widespread opinion, the lexeme svēts in Latvian is a loanword from the Svetlana Ryzhakova 13th-century Old Church Slavonic word svyat Institute of Ethnology [holy] (OCS — *svēts, svyatoi in middle Russian, and Anthropology from the reconstructible Indo-European of the Russian Academy 3 of Sciences, Moscow *ђ&en-) [Endzeīns, Hauzenberga 1934–46]. 1 This article is based on the work for the research project ‘A Historical Recreation of the Structures of Latvian Ethnic Culture’, supported by grant no. 06-06-80278 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, as well as the Programme for Basic Research of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences ‘The Adaptation of Nations and Cultures to Environmental Changes and Social and Anthropo- genic Transformations’ on the theme ‘The Evolution of the Ethnic and Cultural Image of Europe under the Infl uence of Migrational Processes and the Modernisation of Society’. 2 See [CC 1585: 248]; [Enchiridon 1586: 11]; [Mancelius 1638: 90]; [Fürecher II: 469]. -

A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia

religions Article A Reconstructed Indigenous Religious Tradition in Latvia Anita Stasulane Faculty of Humanities, Daugavpils University, Daugavpils LV-5401, Latvia; [email protected] Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 11 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: In the early 20th century, Dievtur¯ıba, a reconstructed form of paganism, laid claim to the status of an indigenous religious tradition in Latvia. Having experienced various changes over the course of the century, Dievtur¯ıba has not disappeared from the Latvian cultural space and gained new manifestations with an increase in attempts to strengthen indigenous identity as a result of the pressures of globalization. This article provides a historical analytical overview about the conditions that have determined the reconstruction of the indigenous Latvian religious tradition in the early 20th century, how its form changed in the late 20th century and the types of new features it has acquired nowadays. The beginnings of the Dievturi movement show how dynamic the relationship has been between indigeneity and nationalism: indigenous, cultural and ethnic roots were put forward as the criteria of authenticity for reconstructed paganism, and they fitted in perfectly with nativist discourse, which is based on the conviction that a nation’s ethnic composition must correspond with the state’s titular nation. With the weakening of the Soviet regime, attempts emerged amongst folklore groups to revive ancient Latvian traditions, including religious rituals as well. Distancing itself from the folk tradition preservation movement, Dievtur¯ıba nowadays nonetheless strives to identify itself as a Latvian lifestyle movement and emphasizes that it represents an ethnic religion which is the people’s spiritual foundation and a part of intangible cultural heritage. -

Citizenship, Official Language, Bilingual Education in Latvia: Public Policy in the Last 10 Years

Citizenship, Official Language, Bilingual Education in Latvia: Public Policy in the Last 10 Years Brigita Zepa This article aims to show the implementation of policies related to ethnic minorities' integration in Latvian society during the first 10 years of Latvia's independence. This aim was postulated because, on the one hand, Latvia is often being criticized for its ethnopolitics both by the EU and by leaders of local minorities. On the other hand, a successful resolution of issues related to ethnopolitics will strengthen Latvian internal stability, ethnic harmony, and open the door to the European Union. The aim of this article is based on the conviction that the analysis and evaluation of ethnopolitics is an important precondition for these policies' improvement, besides acquainting the public with these issues. Although Latvia has been an independent state for already 10 years, many problems, which are still difficult to be solved today, are rooted in conditions that emerged during the Soviet years, when Latvia was a USSR republic. In the first place, migration substantially changed the ethnic composition of Latvia's inhabitants since many migrants moved to Latvia from other republics. Secondly, during the Soviet period the Russian language dominated over Latvian, which led to a restrictive use of Latvian, as the number of people not knowing Latvian grew. When Latvia became an independent state, the said two problems led to the following series of questions that the new legislation had to deal with. These are the laws on citizenship, state language, and education, social integration policies, development of the ethnic relations' model in society. -

Baltic Unity Within European Unity – Why Myth, Not Reality?

1 Baltic Unity within European Unity – why Myth, not Reality? In recent years a debate about development of the European Union (EU) has become hugely important. There are diverse views on the direction of federalism, which the President of the European Commission J. M. D. Barroso is passionately promoting: “Let’s not be afraid of the words: we will need to move towards a federation of nation states. This is what we need. This is our political horizon.”1 As a consequence of such ambitious plans, the question of national identity and independence has become crucial. However, less attention has been paid to the problem of regional cooperation and the effects of already existing European integration on it, which is exactly what this report aims at. In mass media one can often hear about an entity called ‘the Baltic States‘. This union of three states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania has cooperated quite a lot in the two last decades of 20th century, however, now the importance of cooperation seems to be in decline. The Baltic unity in the European unity (i.e. EU) is a myth because of two reasons: passive effect of the integration in the EU, when the European unity indirectly and unintentionally influences the cooperation among the Baltic States, and active effect of the policies of the EU, when they have deliberate impact on the Baltic Unity. Baltic Unity before the EU In order to indicate why Baltic unity is impossible in the context of integrated Europe, it is necessary to recall the common aim of Baltic cooperation before the accession to the European Union. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................................................