"Everything I've Listened to with Love" : a Study of Guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel and His Integration of Classical Music Elements Into Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kontakt: [email protected] Dorotheergasse 10 a – 1010 Wien (Vienna) +43 / 1 / 515 03 - 49

Kontakt: [email protected] Dorotheergasse 10 A – 1010 Wien (Vienna) +43 / 1 / 515 03 - 49 mathias rüegg (*1952 Zürich) (https://www.mathiasrueegg.com) „Meine Tonsprache bezeichne ich als Romantik aus der Sicht von heute, unter Einbeziehung aller musikalischen Entwicklungen seither.“ (mathias rüegg) 1952 in Zürich geboren und in Schiers (GR) aufgewachsen. 1974-76 Musikstudium in Graz 1977 Gründung und Leitung des Vienna Art Orchestra (bis zu dessen Ende 2010 1993 Gründung und Leitung des Jazzclubs Porgy & Bess bis 1995 1997 Gründung und Leitung des Hans Koller Preises bis zu dessen Ende 2010 Seit 2013 Zusammenarbeit mit Lia Pale © Claus Peuckert mathias rüegg wurde 1952 in Zürich geboren. Er machte seinen Abschluss als Primarschullehrer und unterrichtete zunächst an verschiedenen Sonderschulen. Von 1973 bis 1975 studierte er in Graz klassische Komposition & Jazzklavier und übersiedelte 1976 nach Wien, wo er freiberuflich als Pianist arbeitete. Der Soloarbeit müde geworden, gründete er 1977 das Vienna Art Orchestra (VAO), für das er praktisch alle Programme schrieb. Von 1983 bis 1987 leitete er zusätzlich den Vienna Art Choir. Er schrieb u.a. Auftragskompositionen für Jazzformationen wie der NDR Big-Band, SDR Big-Band, UMO Big-Band Helsinki, der Swedish Radio Jazz Group & der RTV Big Band Slovenia. Klassische Aufträge u.a. für die Wiener Symphoniker, Basler Sinfonietta, Ensemble Kontrapunkte, Die Reihe, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, Orchestre de la Normandie Basse, Opus Novum & L’Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana. Als Leiter internationaler Workshops fungierte er u.a. in Wien, Köln, Hannover, Berlin, Bern & Trento. rüegg komponierte Film- und Theatermusiken im Rahmen seiner Zusammenarbeit mit George Tabori und dem Wiener Serapionstheater. Spezielle Projekte zwischen Musik und Literatur verbanden ihn 1983 bis 1990 mit dem Wiener Lyriker Ernst Jandl. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

JAMU 20140416-2 – Vienna Art Orchestra (2) Výběr Z Následujících Alb Orchestru

JAMU 20140416-2 – Vienna Art Orchestra (2) výběr z následujících alb orchestru: ART & FUN Universal Music Emarcy 017 072-2 2002 Live 1-1 Art & Fun 4:26 1-2 L'Art Du Son 7:20 1-3 Art Of Sin 5:59 1-4 Art Is Gone 4:49 1-5 Art Is Smart 5:40 1-6 Art With Heart 8:15 1-7 Art To Dance 3:26 1-8 Art In Trance 4:08 1-9 Art To Lunch 7:12 1-10 Art With Punch 6:47 1-11 Art Got Drunk 4:14 1-12 L'Art Goes Funk 4:35 1-13 Fun & Art 7:21 Remixed 2-1 Artful Noise 4:12 2-2 Son Of Sun 4:20 2-3 Time To Sin 5:07 2-4 Gone Movies 4:44 2-5 Smart Shades 1:57 2-6 Heartbeat 5:02 2-7 Trance Versus Dance 5:39 2-8 Out For Lunch? 5:11 2-9 Dark Water Punch 5:45 2-10 Drunk With Consuela 4:30 2-11 Funkloch 6:32 2-12 Funny Accent 4:17 2-13 Marquis De Satie 6:16 CD1 Recorded at Porgy and Bess, Vienna, August 2001 Mixed at Studio Powerplay, Zurich, January 2002 CD2 All remixes of CD1 at Sonic Spell Lounge/Berlin, November-December 2001 Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love Vol. 2 Universal Music Emarcy 0602498654194 2003 Titles: 1. such sweet thunder 2. very special 3. rem blues 4. after all 5. smada 6. circle in fourths 7. -

Paul Motian Trio and Guest Bass Player Tobiography

www.winterandwinter.com P a u l M o t i a n 25 March 1931 – 22 November 2011 In many interviews, this New York drum- and recordings with Keith Jarrett, Charles mer of Turkish-Armenian extraction has Lloyd and Charlie Haden’s »Liberation been asked time after time for anecdotes Music Ensemble« follow, but over the about Bill Evans, Paul Bley and Keith Jar- years, almost unnoticed, Motian develops rett. His early days attract attention be- his first trio, with Bill Frisell on guitar and cause he was one of the few musicians who Joe Lovano on saxophone. In the mid- can look back on eighties, Motian experiences with begins to collab- Lennie Tristano, orate with Ste- Tony Scott and fan Winter ’s Coleman Haw- newly founded kins, who even music company appeared with JMT Production. Billie Holiday In contrast to and Thelonious the productions Monk in his up to this point, youth, and the first concept played with albums now ap- Arlo Guthrie at pear. The first is the legendary »Monk in Mo- Woodstock Fest- tian«, played by ival. The list of his trio, with great stars Mo- guest musicians tian has played Geri Allen on with goes on for Ꭿ Robert Lewis piano and pages; for some Dewey Redman years he has been reading through his on tenor saxophone. Next comes »Bill painstakingly documented annual calen- Evans«, recorded without pianist by the dars, to stir his memory and write his au- Paul Motian Trio and guest bass player tobiography. Marc Johnson. Winter & Winter, founded at It is not until 1972, at the age of 41, that the end of 1995, takes over and publishes Paul Motian records his debut album under all JMT’s productions, as well as continu- his own name (»Conception Vessel«, with ing work already begun. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

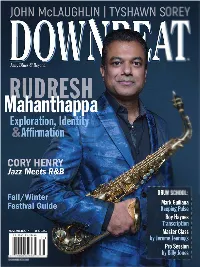

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

Jazz Collection: Lauren Newton (W)

Jazz Collection: Lauren Newton (W) Samstag, 13. Juli 2013, 22.00 - 24.00 Uhr Die Amerikanerin Lauren Newton gilt als eine der wichtigsten zeitgenössischen Vokalimprovisatorinnen. Nach einem klassischen Gesangs- und Kompositionsstudium an der University of Oregon und der Musikhochschule Stuttgart machte sie sich schnell einen Namen in der Jazzszene. Von 1979 bis 1989 war Lauren Newton die Stimme des Vienna Art Orchestra, und prägte den Sound dieses Orchesters massgeblich mit. Mühelos wechselte sie die Rollen von der vierten Stimme im Trompetensatz zur Solistin in Songs und im freien Kontext.Sie trat aber immer auch als Solistin und mit eigenen Vokalensembles auf, nachdem sie 1982 mit einer der stilbildenden Gruppen in diesem Bereich für Furore gesorgt hatte. Im Vocal Summit sang sie neben Bobby McFerrin, Jeanne Lee, Urszula Dudziak und Jay Clayton. Die SRF-Jazzredaktorin Annina Salis hat an der Musikhochschule Luzern bei Lauren Newton studiert und ist Gast von Peter Bürli. Lauren Newton / Vocal Summit: Sorrow Is Not Forever – Love Is CD Moers Music Track 3: Conversations junior Vienna Art Orchestra: The Minimalism Of Erik Satie CD hat ART Track 5: Gnossienne No.3 Lauren Newton: Filigree CD hatOLOGy Track 2: Conversations Track 4: Run Of the Mill Lauren Newton & Thomas Horstmann: Art Is … CD Leo Track 4: Solitude Lauren Newton: Soundsongs CD Leo Track 6: Wordsong Ernst Jandl: Vomvomzumzum LP Extraplatte Track B5: Pi Lauren Newton-Masahiko Togashi-Peter Kowald: Contrast LP Paddle Wheel Track A 2: Twilight South West Lauren Newton & Aki Takase: -

Mehldau-Frisell Notes.Indd

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS ABOUT THE ARTISTS Sunday, January 22, 2006, 7 pm Mehldau’s second solo piano recording, Live Zellerbach Hall in Tokyo, was released in 2004. Day Is Done, the fi rst recording featuring his new trio, was re- leased by Nonesuch in September 2005. It in- cludes interpretations of songs by Lennon and McCartney, Burt Bacharach, Paul Simon and Nick Drake, among others, as well as two original com- positions by Mehldau. Bassist Larry Grenadier received a B.A. in (l–r: Jeff Ballard, Brad Mehldau, Larry Grenadier) English literature from Stanford University. After relocating to Boston, he toured the United States Like many of his contemporaries, pianist Brad and Europe as a member of Gary Burton’s band. Mehldau began his career with intense classical He then moved to New York, where he has per- training long before he was exposed to jazz. He formed with Joe Henderson, Betty Carter, Pat began experimenting with the piano at age four Metheny and John Scofi eld, among others. When and began formal training at six, which continued not working with Brad Mehldau, he tours and re- until he was 14. cords with the Pat Metheny Trio. Brad Mehldau Trio Since arriving in New York in 1988, Mehldau Drummer Jeff Ballard grew up in Santa Cruz, Brad Mehldau, piano has collaborated with many of his musical peers, California. He toured with Ray Charles from 1988 including guitarists Peter Bernstein and Kurt Larry Grenadier, bass until 1990, when he settled in New York. Since Rosenwinkel and tenor saxophonist Mark Turner. Jeff Ballard, drums then, Ballard has performed and recorded with In 1995, he formed his fi rst trio with bassist Larry Lou Donaldson, Danilo Perez, Chick Corea and Grenadier and drummer Jorge Rossy, which toured Joshua Redman, among others. -

Criss Cross › Vienna › Austria Music › Adriane › Muttenthaler

music CRISS CROSS › VIENNA › AUSTRIA MUSIC › ADRIANE › MUTTENTHALER THE BAND DISCOGRAPHY TOURS PRESS THE COMPOSER THE MUSICIANS booking ADRIANE MUTTENTHALER › LAUDONGASSE 21/9 › A-1080 WIEN › AUSTRIA GSM +43680 3019540 [email protected] › WWW.ADRIANE-MUTTENTHALER.AT the band ADRIANE MUTTENTHALER › PIANO, COMPOSITION STEFAN ÖLLERER › SOPRANO SAX CHRISTOPH »PEPE« AUER › ALTO SAX MICHAEL ERIAN › TENOR SAX HEINRICH WERKL › BASS EMIL KRIØTOF › DRUMS CRISS CROSS was founded by Adriane Muttenthaler in 1983 and is at present one of the most distinctive and profound formations in the Austrian jazz scene. CRISS CROSS concerts in Austria and abroad have manifested Austria’s reputation in the world of jazz, and so CRISS CROSS presents a new and really individual swinging and funky emphasis on »modern jazz« and »cross over« making use of all kinds of related styles and experimental fields. The supreme aim of CRISS CROSS is to widen the spectre of extension of contemporary jazz. Adriane Muttenthaler makes use of the manifold possibilities a sextet offers in out- standing arrangements, thus giving the band members opportunities to develop freely their talents for improvisation. CHRISTIAN BAIER booking ADRIANE MUTTENTHALER › LAUDONGASSE 21/9 › A-1080 WIEN › AUSTRIA GSM +43680 3019540 [email protected] › WWW.ADRIANE-MUTTENTHALER.AT discography & tours ASPHALT & NEON (GRAMOLA) › BLACK CHERRIES (GRAMOLA) WITH ADRIANE MUTTENTHALER & ALBERTA GAGGL › VISIONS & REALITIES (EXTRAPLATTE) › KALEIDOSCOPE (EXTRAPLATTE) › PLACES & FACES (PG RECORDS) WITH SPRING STRING -

Vienna Art Orchestra Nightride of a Lonely Saxophoneplayer Vol

Vienna Art Orchestra Nightride Of A Lonely Saxophoneplayer Vol. 1 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Nightride Of A Lonely Saxophoneplayer Vol. 1 Country: Germany Released: 1986 Style: Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1360 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1480 mb WMA version RAR size: 1273 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 363 Other Formats: VOC AU WAV DMF MIDI ADX AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Perpetuum Mobile 10:20 2 4106 6:55 3 Seven Changes 11:05 4 5-String Pinocchio 11:20 5 Lexicon Of Musical Invective 8:20 Ragtime 6 9:20 Arranged By – Uli SchererComposed By – Igor Stravinsky Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Burkhard Hennen Publishing Copyright (c) – Burkhard Hennen Publishing Recorded At – Le Locle Manufactured By – CDP Berlin Credits Alto Saxophone, Flute – Wolfgang Puschnig Bass – Heiri Kaenzig Drums – Joris Dudli Engineer [Sound] – Erich Dorfinger Guitar – Andy Manndorff Keyboards – Uli Scherer Leader, Composed By, Arranged By – Mathias Rüegg Percussion – Tom Nicholas Producer – Burkhard Hennen Recorded By – Peter Pfister Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone, Flute – Harry Sokal Tenor Saxophone, Clarinet – Roman Schwaller Trombone – Christian Radovan Trumpet – Bumi Fian* Trumpet [Lead Trumpet] – Hannes Kottek Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Herbert Joos Tuba – John Sass* Voice – Lauren Newton Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: CDP-BERLIN 02054-5 01 Rights Society: GEMA Label Code: LC 6059 Related Music albums to Nightride Of A Lonely Saxophoneplayer Vol. 1 by Vienna Art Orchestra Wolfgang Fuchs • Hans Koch • Evan Parker • Louis Sclavis - Duets, Dithyrambisch The Hawk-Richard Jazz Orchestra - The Hawk's Out Vienna Art Orchestra - Two Little Animals Saxofour, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Timmy Hutson - 25 Years Of Joy And Fun Burkhard Von Dallwitz - The Orchestra - Noxx Vienna Art Orchestra - Concerto Piccolo Nico Lohmann Quintett - Merging Circles Stefano Battaglia Theatrum - Gesti George Khan - Ah! Depart - Depart Lyle Ritz And His Jazz Ukulele - 50th State Jazz. -

Portrait Mathias Rüegg Anlässlich Seines Geburtstages Am 8

UniCredit\0020 Bank Austria gratuliert mathias rüegg zum 65. Geburtstag – BILD ID: LCG17441 | 19.11.2017 | Kunde: UniCredit Bank Austria AG | Ressort: Kultur Österreich | Medieninformation Als langjähriger Wegbegleiter und Unterstützer von mathias rüegg gratuliert die UniCredit Bank Austria zum 65. Geburtstag. Rund um seinen Ehrentag am 8. Dezember 2017 porträtiert ein dreitägiges Kulturprogramm von 7. bis 9. Dezember 2017 im Porgy & Bess das Leben und Schaffen des Gründers des Vienna Art Orchestras. Bilder zur Meldung auf http:// presse.leisuregroup.at/ bankaustria/ ruegg Wien (LCG) – Über Jahre hinweg war die UniCredit Bank Austria in vielerlei Hinsicht eng mit dem Komponisten und Musiker, der Jazzikone mathias rüegg verbunden. „mathias rüegg ist eine außergewöhnliche Musikergröße! Er versteht es, die Grenzen von Jazz bis Klassik auszuloten und Musikgeschichte zu schreiben; zuletzt zeichnete er für die viel beachtete Neukomposition des ‚Jedermann’ verantwortlich. Als langjähriger Sponsor des von rüegg geleiteten Vienna Art Orchestras, des ebenfalls von ihm gegründeten Porgy & Bess und des Hans Koller Preises blicken wir auf eine erfolgreiche gemeinsame Geschichte zurück und gratulieren ihm herzlich zum 65. Geburtstag“, so Anton Kolarik , Leiter Identity & Communications in der UniCredit Bank Austria. Portrait mathias rüegg Anlässlich seines Geburtstages am 8. Dezember 2017 porträtiert ein dreitägiges Programm mit musikalischen Schmankerln und Diskussionen im Porgy & Bess das Leben von mathias rüegg . Unter anderem mit dabei: Konrad Paul Liessmann,Wolfram Berger ,Wolfgang Puschnig ,Lauren Newton ,Harry Sokal,Wolfgang Reisinger ,Mario Rom undLia Pale. Den Auftakt am 7. Dezember 2017 gestaltet rüegg als „The Arranger“ und sorgt für die lang ersehnte Reunion des Vienna Art Orchestras mit einer Neuauflage des erfolgreichen Programmes von 1983, „The Minimalism of Erik Satie“.