Prison Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

Print Complete Desire Full Song List

R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘50s/ ‘60s MUSIC ARETHA FRANKLIN: ISLEY BROTHERS: SAM COOK: RESPECT SHOUT TWISTIN THE NIGHT AWAY NATURAL WOMAN JAMES BROWN: YOU SEND ME ARTHUR CONLEY: I FEEL GOOD SMOKEY ROBINSON & THE MIRACLES: SWEET SOUL MUSIC I'T'S A MAN'S MAN'S WORLD OOH BABY BABY DIANA ROSS & THE SUPREMES: PLEASE,PLEASE,PLEASE TAMS: BABY LOVE LLOYD PRICE: BE YOUNG BE FOOLISH BE HAPPY STOP! IN THE NAME OF LOVE STAGGER LEE WHAT KIND OF FOOL YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE MARY WELLS: TEMPTATIONS: YOU KEEP ME HANGIN ON MY GUY AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG DION: MARTHA & THE VANDELLAS: I WISH IT WOULD RAIN RUN AROUND SUE DANCING IN THE STREET MY GIRL DRIFTERS & BEN E. KING: HEATWAVE THE WAY YOU DO THE THINGS YOU DO DANCE WITH ME MARVIN GAYE: THE DOMINOES: I’VE GOT SAND IN MY SHOES AIN’T NOTHING LIKE THE REAL THING SIXTY MINUTE MAN RUBY RUBY HOW SWEET IT IS TO BE LOVED BY YOU TINA TURNER: SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE MOVIES I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE PROUD MARY STAND BY ME OTIS REDDING: WILSON PICKET: THERE GOES MY BABY DOCK OF THE BAY 634-5789 UNDER THE BOARDWALK THAT’S HOW STRONG MY LOVE IS DON’T LET THE GREEN GRASS FOOL YOU UP ON TH ROOF PLATTERS: IN THE MIDNIGHT HOUR EDDIE FLOYD: WITH THIS RING MUSTANG SALLY KNOCK ON WOOD RAY CHARLES ETTA JAMES: GEORGIA ON MY MIND AT LAST SAM AND DAVE: FOUR TOPS: HOLD ON I'M COMING BABY I NEED YOUR LOVING SOUL MAN CAN'T HELP MYSELF REACH OUT I'LL BE THER R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘70s MUSIC AL GREEN: I WANT YOU BACK ROD STEWART: LOVE AND HAPPINESS JAMES BROWN: DA YA THINK I’M SEXY? ANITA WARD: GET UP ROLLS ROYCE: RING MY BELL THE PAYBACK CAR WASH BILL WITHERS: JIMMY BUFFETT: SISTER SLEDGE: AIN’T NO SUNSHINE MARGARITAVILLE WE ARE FAMILY BRICK: K.C. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Alternative Performances of Race and Gender in Hip-Hop Music : Nerdcore Counterculture

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2012 Alternative performances of race and gender in hip-hop music : nerdcore counterculture. Jessica Elizabeth Ronald University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ronald, Jessica Elizabeth, "Alternative performances of race and gender in hip-hop music : nerdcore counterculture." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1231. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1231 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALTERNATNE PERFORMANCES OF RACE AND GENDER IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: NERDCORECOUNTERCULTURE By Jessica Elizabeth Ronald B.A., Women's and Gender Studies 2008 M.A., Women's and Gender Studies 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Pan African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2012 ALTERNATIVE PERFORMANCES OF RACE AND GENDER IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: NERDCORE COUNTERCULTURE By Jessica Ronald B.A., Women’s and Gender Studies 2008 M.A., Women’s and Gender Studies 2010 A Thesis Approved on April 18, 2012 by the following Thesis Committee: Dr. -

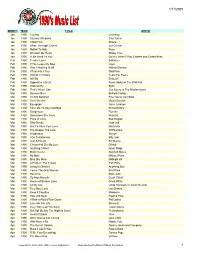

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

"Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 "Now I Ain't Sayin' She's a Gold Digger": African American Femininities in Rap Music Lyrics Jennifer M. Pemberton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES “NOW I AIN’T SAYIN’ SHE’S A GOLD DIGGER”: AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMININITIES IN RAP MUSIC LYRICS By Jennifer M. Pemberton A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Jennifer M. Pemberton defended on March 18, 2008. ______________________________ Patricia Yancey Martin Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Dennis Moore Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Jill Quadagno Committee Member ______________________________ Irene Padavic Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Irene Padavic, Chair, Department of Sociology ___________________________________ David Rasmussen, Dean, College of Social Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my mother, Debra Gore, whose tireless and often thankless dedication to the primary education of children who many in our society have already written off inspires me in ways that she will never know. Thank you for teaching me the importance of education, dedication, and compassion. For my father, Jeffrey Pemberton, whose long and difficult struggle with an unforgiving and cruel disease has helped me to overcome fear of uncertainty and pain. Thank you for instilling in me strength, courage, resilience, and fortitude. -

Slavery As a Form of Racialized Social Control

TEACHING TEACHING The New Jim Crow TOLERANCE LESSON 3 A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER TOLERANCE.ORG Slavery as a Form of Racialized Social Control THE NEW JIM CROW by Michelle Alexander CHAPTER 1 The Rebirth of Caste The Birth of Slavery The concept of race is a relatively recent development. Only in the past few centuries, ow- ing largely to European imperialism, have the world’s people been classified along racial lines.1 Here, in America, the idea of race emerged as a means of reconciling chattel slavery— as well as the extermination of American Indians—with the ideals of freedom preached by whites in the new colonies. BOOK In the early colonial period, when settlements remained relatively small, EXCERPT indentured servitude was the dominant means of securing cheap labor. Under this system, whites and blacks struggled to survive against a com- mon enemy, what historian Lerone Bennett Jr. describes as “the big planter apparatus and a social system that legalized terror against black and white bonds-men.”2 Initially, blacks brought to this country were not all enslaved; many were treated as indentured servants. As plantation farming expanded, particularly tobacco and cotton farming, demand increased greatly for both labor and land. The demand for land was met by invading and conquering larger and larger swaths of terri- tory [held by American Indians]. Abridged excerpt from The New Jim The growing demand for labor on plantations was met through slavery. American Indians Crow: Mass Incar- were considered unsuitable as slaves, largely because native tribes were clearly in a posi- ceration in the Age tion to fight back. -

1 GRAAT On-Line Occasional Papers – December 2008 Representing The

GRAAT On-Line Occasional Papers – December 2008 Representing the Dirty South: Parochialism in Rap Music David Diallo Université Montesquieu – Bordeaux IV In this article, divided into two parts, I examine the parochial discourse of rap musicians from the Dirty South and study its symbolic stakes through a socio- historical analysis of hip-hop’s cultural practices. First, I address the importance for Southern hip hop musicians of mentioning their geographic origins. They develop slang, fashion style, musical and lyrical structures meant to represent the Dirty South. In part II, I examine the Dirty South rap scene, and point out some of its characteristics and idiosyncrasies. Rap historians generally consider that, before 1979, hip hop was a local phenomenon that had spread out geographically in poor neighborhoods around New York (Ogg 2002, Fernando 1994, George 2001). Chronologically, Kool Herc, using the principle of Jamaican sound system, defined the norms of reference for hip hop deejaying and determined the standard way to accomplish this practice. His style and technique established the elemental structure of rap music and determined the “proper” way to make rap. It is particularly interesting to note that the emerging sound system scene in the Bronx was spatially distributed as follows. Kool Herc had the West Side, Afrika Bambaataa had Bronx River, and Grandmaster Flash had the South Bronx, from 138 th Street up to Gun Hill. This parting of the Bronx into sectors (DJs’ territories) distinguished the locations that covered the key operative areas for the competing 1 sound systems. This spatial distribution reveals rap music’s particular relationship to specified places. -

Hip Hop Studies at the Library

Hip Hop Studies at the Library A study guide from the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre (AIU Centre), University of Manchester Contents Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 What is Hip Hop Studies? .................................................................... 2 Where to Start .................................................................................... 3 Books in the Library ............................................................................ 5 Hip Hop Culture .......................................................................... 5 US / World Race Relations and Hip Hop ................................... 13 Hip Hop Education ................................................................... 18 Gender / Feminism Studies ...................................................... 19 Black Film Studies ..................................................................... 22 Hip Hop Lesson Plans ........................................................................ 24 English Literature and Language .............................................. 24 History ...................................................................................... 26 Geography ................................................................................ 27 Sociology .................................................................................. 27 Further Reading ................................................................................ 29 Related -

Brevard Live October 2018

Brevard Live October 2018 - 1 2 - Brevard Live October 2018 Brevard Live October 2018 - 3 4 - Brevard Live October 2018 Brevard Live October 2018 - 5 6 - Brevard Live October 2018 Contents October 2018 FEATURES FRANNIPALOOZA Franni’s music quest started in 1980 WAR COMES TO BREVARD when she arrived in Florida. She worked Columns War, featuring original member Lonnie for years at the legendary Musicians Ex- Charles Van Riper Jordan, is coming to Brevard to play all change in Fort Lauderdale. Now she is 20 Political Satire their greatest hits…and there are quite a booking famous Blues artists at Earl’s It’s That Time few. The concert takes place at SC Har- Hideaway. She truly is a legend among ley Davidson and benefits The Great legends. Brevard Live talked to her. Calendars Leaps Academy. Page 14 27 Live Entertainment, Page 10 Concerts, Festivals WOMEN WHO ROCK! SPACE COAST STATE FAIR Karalyn Woulas is a rocket scientist, an The Mandela Effect The Space Coast State Fair is Brevard’s avid surfer, front-lady of 2 bands - The by Matt Bretz largest and most popular annual family 35 Lady & The Tramps and Karalyn & The Human Satire event. Located in the middle of Brevard Dawn Patrol - a politician and enjoys County, and easily accessible from Inter- riding her Harley Davidson Sportster. state-95, The Space Coast State Fair is a Local Lowdown short ride from all areas of Brevard Page 18 36 by Steve Keller Page 13 Jam Night! MIFF PROGRAM by Heike Clarke NATIVE RHYTHMS FESTIVAL The Melbourne Independent Filmmak- 39 The 10th annual Native Rhythms Fes- ers Festival is a jewel for fans of the in- The Dope Doctor tival will be held at the Wickham Park dependent short film. -

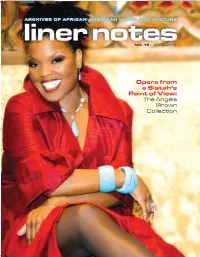

Opera from a Sistah's Point of View

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notes NO. 15 / 2010-2011 Opera from a Sistah’s Point of View: The Angela Brown Collection aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and I write this column as we enter into be of use to others.” Although Brown’s dissemination of materials for the second decade of the twenty-first career continues to evolve, Head of the purpose of research and century and as I reflect on the political, Collections Brenda Nelson-Strauss study of African American social, and cultural changes that have believes that “starting the archiving music and culture. taken place during the first ten years process now is advantageous from an www.indiana.edu/~aaamc of this new millennium. Within this archivist’s perspective because of the context of change, I marvel at the ways opportunity to evaluate and preserve in which African Americans continue materials initially, then annually, as new to expand and redefine the boundaries materials are created. I think things are Table of Contents for artistic expressions, revealing the less likely to fall through the cracks if we diversity of musical creativity among have a more active role in documenting From the Desk of this group. Two major collections Angela Brown’s career.” We look forward the Director ......................................2 acquired in 2010—the Angela Brown to our ongoing relationship with Angela Collection and the James Spooner Brown (see inside story). Featured Collection: Collection—reveal the ways in which Following the AAAMC’s November Angela Brown ..................................4 African Americans negotiate their dual 2009 conference, Reclaiming the Right to identities as performers in Western Rock: Black Experiences in Rock Music, In the Vault: classical traditions and how they several of the participants donated Recent Donations .........................8 construct and define black identities in items ranging from CDs to posters.