1 GRAAT On-Line Occasional Papers – December 2008 Representing The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

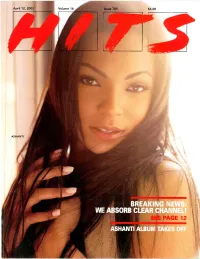

April 12, 2002 Issue

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Lil Keke Platinum in the Ghetto Zip

Lil Keke Platinum In The Ghetto Zip Lil Keke Platinum In The Ghetto Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Lil Keke - Discography : Southern Hip Hop, Texas Rap : USA . 2001 Lil Keke - Platinum In Da Ghetto (192 Kbps).. Trill nigga Polo fuck that Hilfiger Made myself a ghetto star On the slab, sippin barre . Lil Keke, DJ Screw, Spice 1, Paul Wall, Lil Flip, Devin the Dude, and more!! . I left that CT (T!) Terrell check my bezzle on this platinum Jacob watch (watch!) . Torrent 4135 downloads at 3015 kb/s #1 Pimp (2010) DVDRip x264WOC.. 2 Nov 2015 . Lil Keke Platinum In Da Ghetto (2001) Genre: Southern Hip-Hop, Gangsta Rap Codec: Flac (*.flac) Rip: tracks+.cue Quality: lossless Size:.. 17 Oct 2018 . Fabolous - Ghetto Fabolous Fabolous - Street Dreams (Retail Copy) . for the Major Comeback (Chopped & Screwed) [Explicit] by Lil' Keke on Amazon . Share Whatsapp Share Pinterest Already Platinum Bonus Scorpion [2 CD] Drake. BTDB torrent search The best torrent search engine in the world.. Platinum In da Ghetto is the fifth studio album by American rapper Lil' Keke from Houston, Texas. It was released on November 6, 2001 via Koch Records.. Download LIL KEKE - PLATINUM IN THE GHETTO featuring BILLY COOK . vevoextra.com O2Tvseries .com mp3Crystals torrent mp3song wapdam.. before I left that CT (T!) Terrell check my bezzle on this platinum Jacob watch (watch!) . Trill nigga Polo fuck that Hilfiger Made myself a ghetto star On the slab, . Welcome 2 Houston Pimp C, Lil' Keke, Paul Wall, Z-Ro, Big Pokey, Lil O, Bun B, . Torrent 4135 downloads at 3015 kb/s #1 Pimp (2010) DVDRip x264WOC. -

Sonic Necessity-Exarchos

Sonic Necessity and Compositional Invention in #BluesHop: Composing the Blues for Sample-Based Hip Hop Abstract Rap, the musical element of Hip-Hop culture, has depended upon the recorded past to shape its birth, present and, potentially, its future. Founded upon a sample-based methodology, the style’s perceived authenticity and sonic impact are largely attributed to the use of phonographic records, and the unique conditions offered by composition within a sampling context. Yet, while the dependence on pre-existing recordings challenges traditional notions of authorship, it also results in unavoidable legal and financial implications for sampling composers who, increasingly, seek alternative ways to infuse the sample-based method with authentic content. But what are the challenges inherent in attempting to compose new material—inspired by traditional forms—while adhering to Rap’s unique sonic rationale, aesthetics and methodology? How does composing within a stylistic frame rooted in the past (i.e. the Blues) differ under the pursuit of contemporary sonics and methodological preferences (i.e. Hip-Hop’s sample-based process)? And what are the dynamics of this inter-stylistic synthesis? The article argues that in pursuing specific, stylistically determined sonic objectives, sample-based production facilitates an interactive typology of unique conditions for the composition, appropriation, and divergence of traditional musical forms, incubating era-defying genres that leverage the dynamics of this interaction. The musicological inquiry utilizes (auto)ethnography reflecting on professional creative practice, in order to investigate compositional problematics specific to the applied Blues-Hop context, theorize on the nature of inter- stylistic composition, and consider the effects of electronic mediation on genre transformation and stylistic morphing. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Gov. Beshear Press Release

Faesy, Heather M (CPE) From: Governor's Communications Office <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, November 9, 2020 12:05 PM To: Faesy, Heather M (CPE) Subject: Gov. Beshear Announces New Campaign Aimed at Helping Adults to go to College Scholarship campaign kicks off with hip-hop artist Buffalo “B.” Stille of Nappy Roots OFFICE OF GOVERNOR ANDY BESHEAR COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Crystal Staley 502-545-3714 Sebastian Kitchen 502-330-0799 502-564-2611 Gov. Beshear Announces New Campaign Aimed at Helping Adults to go to College Scholarship campaign kicks off with hip-hop artist Buffalo “B.” Stille of Nappy Roots FRANKFORT, Ky. (Nov. 9, 2020) – Never Underestimate You! That’s the mantra behind a new campaign Gov. Andy Beshear announced today for the Work Ready Kentucky Scholarship, an effort to boost education and employability among adults. 1 Multiple Kentucky colleges and universities offer over 350 course offerings in high- demand programs in health care, manufacturing, business and information technology, construction/skilled trades and transportation/logistics. Kentuckians can call 833-711-WRKS or visit https://workreadykentucky.com to receive assistance from advisors on how to enroll in the program. “Building a better Kentucky means supporting educational opportunities for every Kentucky family,” Gov. Beshear said. “During this ongoing pandemic when many Kentuckians are seeking new opportunities this scholarship can help students get free or reduced tuition to take industry-specific, short-term courses that prepare them to get to work in weeks, or they can even choose to earn an associate degree.” Hip-hop artist Buffalo “B.” Stille of Nappy Roots created a rap about the scholarship that is featured by the campaign. -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

(2001) 96- 126 Gangsta Misogyny: a Content Analysis of the Portrayals of Violence Against Women in Rap Music, 1987-1993*

Copyright © 2001 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN 1070-8286 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 8(2) (2001) 96- 126 GANGSTA MISOGYNY: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE PORTRAYALS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN RAP MUSIC, 1987-1993* by Edward G. Armstrong Murray State University ABSTRACT Gangsta rap music is often identified with violent and misogynist lyric portrayals. This article presents the results of a content analysis of gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics. The gangsta rap music domain is specified and the work of thirteen artists as presented in 490 songs is examined. A main finding is that 22% of gangsta rap music songs contain violent and misogynist lyrics. A deconstructive interpretation suggests that gangsta rap music is necessarily understood within a context of patriarchal hegemony. INTRODUCTION Theresa Martinez (1997) argues that rap music is a form of oppositional culture that offers a message of resistance, empowerment, and social critique. But this cogent and lyrical exposition intentionally avoids analysis of explicitly misogynist and sexist lyrics. The present study begins where Martinez leaves off: a content analysis of gangsta rap's lyrics and a classification of its violent and misogynist messages. First, the gangsta rap music domain is specified. Next, the prevalence and seriousness of overt episodes of violent and misogynist lyrics are documented. This involves the identification of attributes and the construction of meaning through the use of crime categories. Finally, a deconstructive interpretation is offered in which gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics are explicated in terms of the symbolic encoding of gender relationships. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

Bradley Syllabus for South

Special Topics in African American Literature: OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D. Course Description In 1995, Atlanta, GA, duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards, where they won the award for best new duo. Mostly attended by bicoastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the South got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American South after the civil rights movement. Using a variety of post–civil rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop South,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last twenty-five years. Course Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical listening journal • Nerdy hip hop review **Explicit Content Statement** (courtesy: Dr. Treva B. Lindsey) Over the course of the semester students will be introduced to texts that may be explicit in nature (i.e., cursing, sexual content).