Opera from a Sistah's Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant Interview conducted by Sharon Press1 SHARON: Thanks for letting me interview you. Let’s start with a little bit of background on John Thompson. Tell me about where you grew up. JOHN: I grew up on the south side of Chicago in a predominantly black neighborhood. I at- tended Henry O Tanner Elementary School in Chicago. I know throughout my time in Chicago, I always wanted to be a basketball player, so it went from wanting to be Dr. J to Michael Jordan, from Michael Jordan to Dennis Rodman, and from Dennis Rodman to Charles Barkley. I actu- ally thought that was the path I was gonna go, ‘cause I started getting so tall so fast at a young age. But Chicago was pretty rough and the public-school system in Chicago was pretty rough, so I come here to Minnesota, it’s like a culture shock. Different things, just different, like I don’t think there was one white person in my school in Chicago. SHARON: …and then you moved to Minnesota JOHN: I moved to Duluth Minnesota. I have five other siblings — two sisters, three brothers and I’m the baby of the family. Just recently I took on a program called Safe, and it’s a mentor- ship program for children, and I was asked, “Why would you wanna be a mentor to some of these mentees?” I said, “’Cause I was the little brother all the time.” So when I see some of the youth it was a no brainer, I’d be hypocritical not to help, ‘cause that’s how I was raised… from the butcher on the corner or my next-door neighbor, “You want me to call your mother on you?” If we got out of school early, or we had an early release, my mom would always give us instructions “You go to the neighbor’s house”, which was Miss Hollandsworth, “You go to Miss Hollandsworth’s house, and you better not give her no problems. -

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Management Message 02 At the center of our businesses 04 12 Group Profi le | Businesses | Societal, Social and Litigation | Risk Factors 07 Environmental Information 41 1. Group Profi le 09 1. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Policy 42 2. Businesses 20 2. Societal Information 47 3. Litigation 32 3. Social Information 62 4. Risk Factors 38 4. Environmental Information 77 5. Verifi cation of Non-Financial Data 85 3 Information about the Company | Corporate Governance | Reports 91 1. General Information about the Company 92 2. Additional Information about the Company 93 3. Corporate Governance 106 4. Report by the Chairman of Vivendi’s Supervisory Board on Corporate Governance, Internal Audits and Risk Management – Fiscal Year 2014 147 5. Statutory Auditors’ report, prepared in accordance with Article L.225-235 of the French Commercial Code, on the Report prepared by the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Vivendi SA 156 4 Financial Report | Statutory Auditors’ Report on the Consolidated Financial Statements | Consolidated Financial Statements | Statutory Auditors’ Report on the Financial Statements | Statutory Financial Statements 159 Selected key consolidated fi nancial data 160 I - 2014 Financial Report 161 II - Appendices to the Financial Report: Unaudited supplementary fi nancial data 191 III - Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2014 195 IV - Vivendi SA - 2014 Statutory Financial Statements 294 56 Recent events | Outlook 337 Responsibility for Auditing 1. Recent events 338 the Financial Statements 341 2. Outlook 339 1. Responsibility for Auditing the Financial Statements 342 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French “Document de référence” provided for information purposes. -

Dayton Opera Artistic Director Thomas Bankston to Retire at the Conclusion of His 25Th Season with Dayton Opera in June 2021

Dayton Opera Artistic Director Thomas Bankston to Retire at the Conclusion of His 25th Season with Dayton Opera in June 2021 CONTACT: ANGELA WHITEHEAD Communications & Media Manager Dayton Performing Arts Alliance Phone 937-224-3521 x 1138 [email protected] DAYTON, OH (February 7, 2020) – The Dayton Performing Arts Alliance (DPAA) has announced today that Thomas Bankston, Artistic Director of Dayton Opera, will retire in June 2021, at the conclusion of the newly announced 2020–2021 Celebrate Season, Dayton Opera’s 60th anniversary season. “The coming together of three especially celebratory events in the 2020-21 season – Dayton Opera’s 60th anniversary, my 25th season, and the closing of that season with a world premiere opera production, Finding Wright – seemed like a fitting time at which to bring to a close my 41 year career in the professional opera business. Dayton Opera has been a huge part of my life and will always hold a special place in my heart. Especially all the wonderful friendships and associations I have made with artists, staff and volunteers that will make my retirement a truly bittersweet one,” said Tom Bankston. The 2020–2021 season will mark Bankston’s 25th season providing artistic leadership for Dayton Opera, the longest term of artistic leadership in the company’s history. In 1996, he began his work with the company, sharing his wide-ranging knowledge of the field of opera between Dayton Opera and Cincinnati Opera, the company where in 1982 he began his work as an opera administrator. At the start of the 2001–2002 season, he left Cincinnati Opera and assumed the position of Artistic Director for Dayton Opera on a full-time basis, and then was named General & Artistic Director of Dayton Opera in 2004. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

Zayn's Debut Album Mind of Mine out March 25

ZAYN’S DEBUT ALBUM MIND OF MINE OUT MARCH 25TH WORLDWIDE AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER NOW TRACKLISTING REVEALED The track listing for ZAYN’s highly anticipated debut album MIND OF MINE has been announced. The standard edition features the following songs: 1.MiNd Of MiNdd 2.PiLlOwT4lK 3.iT’s YoU 4.BeFoUr 5.sHe 6.dRuNk 7.INTERMISSION: fLoWer 8.rEaR vIeW 9.wRoNg 10.fOoL fOr YoU 11. BoRdErz 12.tRuTh 13.lUcOzAdE 14.TiO With the deluxe edition featuring an extra four: 15. BLUE 16. BRIGHT 17. LIKE I WOULD 18. SHE DON’T LOVE ME Target will be releasing a deluxe exclusive version of ZAYN’s MIND OF MINE, which features 2 extra songs not available on the standard deluxe release: 19. DO SOMETHING GOOD 20. GOLDEN All three editions are now available for pre-order and in advance of the March 25th album release, fans will instantly receive the tracks “iT's YoU” and “PILLOWTALK” upon pre-ordering. The video for “iT's YoU” is available exclusively on Apple Music, and is directed by Ryan Hope. “PILLOWTALK,” the first single from MIND OF MINE truly cemented ZAYN as one of the most exciting solo artist of the time. Upon release, the single debuted at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart, #1 on the U.S. Digital Songs Chart, #1 on the U.K. singles sales charts, and #1 on Billboard’s On Demand Songs Chart. The video for “PILLOWTALK” has now amassed over 180 million views. Follow ZAYN Twitter: https://twitter.com/zaynmalik Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/ZAYN Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/ZAYN Spotify Artist Page: http://smarturl.it/ZAYNSpotify Website: http://www.inZAYN.com -

Images of Aggression and Substance Abuse in Music Videos : a Content Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis Monica M. Escobedo San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Escobedo, Monica M., "Images of aggression and substance abuse in music videos : a content analysis" (2009). Master's Theses. 3654. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.qtjr-frz7 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF AGGRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE IN MUSIC VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Monica M. Escobedo May 2009 UMI Number: 1470983 Copyright 2009 by Escobedo, Monica M. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

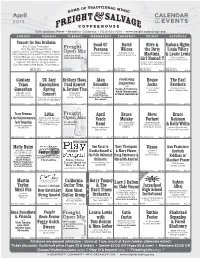

April CALENDAR of EVENTS

April CALENDAR 2013 OF EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Concert for Sue Draheim eric & Suzy Thompson, Good Ol’ David Olive & Barbara Higbie, Jody Stecher & kate brislin, Freight laurie lewis & Tom rozum, kathy kallick, Persons Wilcox the Dirty Linda Tillery Open Mic California bluegrass the best of pop Gerry Tenney & the Hard Times orchestra, pay your dues, trailblazers’ reunion and folk aesthetics Martinis, & Laurie Lewis Golden bough, live oak Ceili band with play and shmooze Hills to Hollers the Patricia kennelly irish step dancers, Girl Named T album release show Tempest, Will Spires, Johnny Harper, rock ‘n’ roots fundraiser don burnham & the bolos, Tony marcus for the rex Foundation $28.50 adv/ $4.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $24.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $22.50 adv/ $30.50 door monday, April 1 $6.50 door Apr 2 $22.50 door Apr 3 $26.50 door Apr 4 $22.50 door Apr 5 $24.50 door Apr 6 Gautam UC Jazz Brittany Haas, Alan Celebrating House The Earl Songwriters Tejas Ensembles Paul Kowert Senauke with Jacks Brothers Zen folk musician, Caren Armstrong, “the rock band Outlaw Hillbilly Ganeshan Spring & Jordan Tice featuring Keith Greeninger without album release show Carnatic music string fever Jon Sholle, instruments” with distinction Concert from three Chad Manning, & Steve Meckfessel and inimitable style featuring the Advanced young virtuosos Suzy & Eric Thompson, Combos and big band Kate Brislin $20.50/$22.50 Apr 7 $14.50/$16.50 Apr -

The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts Presents Two Performances Perfect for the Whole Family!

April 14, 2010 The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts presents two performances perfect for the whole family! LA-based drum, music and dance ensemble STREET BEAT combines urban rhythms, hip-hop moves and break dance acrobatics into an explosive, high-energy performance Grammy ® nominated vocal ensemble Linda Tillery & the Cultural Heritage Choir share the rich traditions of African American Roots music (Philadelphia, April 14, 2010) — The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts presents not one but two performances perfect for the whole family. First, the high-energy, LA-based drum, music and dance ensemble STREET BEAT combine urban rhythms, hip-hop moves and break dance acrobatics into one explosive performance on Thursday, April 29, 2010 at 7:30 PM at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets for the performance start at just $10. On Friday, April 30, 2010 at 8:00 PM, Linda Tillery & The Cultural Heritage Choir, a Grammy® nominated, five member-strong a cappella ensemble embark on an illuminating and highly spirited journey of African American history. The ensemble’s mission is to help preserve and share the rich musical traditions of African American roots music with a repertoire that runs the gamut from spirituals, gospel, blues, jazz, funk, soul and hip-hop. Tickets for the performance are $25 or $40. For tickets or for more information, please visit AnnenbergCenter.org or call 215.898.3900. Tickets can also be purchased in person at the Annenberg Center Box Office. Both artists are also featured main stage performers during the 26th annual Philadelphia International Children’s Festival taking place at the Annenberg Center April 27-May 1, 2010. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing.