Gender in Motion: Exceeding Heteronormative Codes in Salsa Dancing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

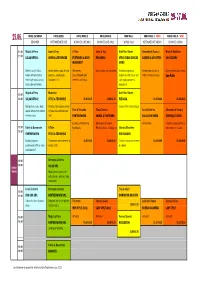

Son Patin Linear Style Salsa, Basics Isolation (On1) Elements of Rumba

25.06. HOTEL KATARINA HOTEL EDEN HOTEL PARK 1 HOTEL PARK 2 MMC HALL ADRIS HALL 1 - NEW! ADRIS HALL 2 - NEW! BEGINNER INTERMMEDIATE LINE ADVANCED LINE (ON1) ADVANCED LINE (ON2) WORLD SALA INTERMMEDIATE CUBAN ADVANCED CUBAN 11:00 Matjaž & Petra Jorjet & Troy U-Tribe Jorjet & Troy Ariel Rios Robert Alexander & Yunaisy Mario & Madeline 11:50 SALSA INTRO 1 SHINES & TECHNIQUE FOOTWORK & BODY PACHANGA AFRO-CUBAN DANCES DANZON & SON INTRO SON CUBANO MOVEMENT INTRO What is salsa? Salsa Simple shines, body & hand Afro shines. Basics steps and variations.History background, Introductory classes in Clave, rhythm, basic steps history. Introduction in postures, simple body Salsa footwork with importance for dance and Cuban national dances. Son Patin linear style salsa, basics isolation (On1) elements of rumba. style, body posture & steps, demonstration. movement Matjaž & Petra Mambata Ariel Rios Robert 12:00 12:50 SALSA INTRO 2 STYLE & TECHNIQUE 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 ELEGGUA 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 Bod posture, cross body Fluidity, style & body control Dance of the orisha Elegua lead & simple turn pattern in linear salsa partnerwork Fran & Veronika Tito & Tamara Israel Gutierrez Alexander & Yunaisy in linear salsa (On1) PARTNERWORK SHINES & FOOTWORK SALSA CON TIMBA TECHNIQUE WORK Leading and following Working on technique. Partnerwork Footwork, body posture & 13:00 Fabris & Rosemarie U-Tribe techniques PR style shines - building up Mario & Madeline movements in Casino 13:50 PARTNERWORK STYLE & TECHNIQUE from simple to advanced SON CUBANO Building up your Partnerwork with elements of 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 Tornillos variations for men 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 partnerwork. -

Redalyc."Somos Cubanos!"

Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música E-ISSN: 1697-0101 [email protected] Sociedad de Etnomusicología España Froelicher, Patrick "Somos Cubanos!" - timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música, núm. 9, diciembre, 2005, p. 0 Sociedad de Etnomusicología Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82200903 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Somos Cubanos! Revista Transcultural de Música Transcultural Music Review #9 (2005) ISSN:1697-0101 “Somos Cubanos!“ – timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Patrick Froelicher Abstract The complex processes that led to the emergence of salsa as an expression of a “Latin” identity for Spanish-speaking people in New York City constitute the background before which the Cuban timba discourse has to be seen. Timba, I argue, is the consequent continuation of the Cuban “anti-salsa-discourse” from the 1980s, which regarded salsa basically as a commercial label for Cuban music played by non-Cuban musicians. I interpret timba as an attempt by Cuban musicians to distinguish themselves from the international Salsa scene. This distinction is aspired by regular references to the contemporary changes in Cuban society after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thus, the timba is a “child” of the socialist Cuban music landscape as well as a product of the rapidly changing Cuban society of the 1990s. -

Cuban Salsa and Rueda De Casino

27 Cuban Salsa and Rueda de Casino Note: Much of the material below appeared in the Final syllabus for the 2014 Stockton Folk Dance Camp, including the photographs showing the various hand signals. Some introductory material has been added, as well as some new figures. Cuban Salsa (“Casino”) and Rueda de Casino (roo-EH-thah theh kah-SEE-noh) emerged in Cuba in the second half of the 20th century, a “Salsa” emerging from the rich mix of dances and rhythms already thriving throughout the island, including Son, Cha Cha Cha, Mambo, and multiple African-based expressions. The widespread global popularity of Cuban Salsa speaks to the depth of its roots in Afro- Cuban traditions and its capacity to keep growing and re-rooting in new places. “Casino” refers to Cuban-style salsa in partners, while “Rueda de Casino” is a circle or wheel (rueda) of partners dancing in unison in response to the calls of the leader in the group. “Calls” in a Rueda include turn patterns, footwork sequences, and various games. Many of the calls for Rueda in Cuba speak to pop-culture themes and expressions, a repertoire that can expand and adapt to the many local cultures it encounters as it spreads throughout the globe. Many students new to dance, or new to this form, find Cuban Salsa to be a joyful and social opportunity to rediscover a more easeful, natural way of being in their bodies. Cuban Salsa does not prescribe “style” but allows for discovery of the beauty and sensuality of each individual body in motion. -

Identity, Meaning, and the Kinesthetic Language of Cuban Casino Dancing Brian Martinez

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 ¡Casinando!: Identity, Meaning, and the Kinesthetic Language of Cuban Casino Dancing Brian Martinez Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ¡CASINANDO! IDENTITY, MEANING, AND THE KINESTHETIC LANGUAGE OF CUBAN CASINO DANCING By BRIAN MARTINEZ A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Brian Martinez defended this thesis on March 26, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Frank Gunderson Professor Directing Thesis Michael Bakan Committee Member Charles Brewer Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my father, mother, and brother, for all of your unfailing love and support iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................................... vii ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................................. ix 1. INTRODUCTION TO CASINO ..........................................................................................1 -

The European Salsa Congress Music and Dance in Transnational Circuits Ananya Jahanara Kabir

C h a p t e r 1 5 The European Salsa Congress Music and Dance in Transnational Circuits Ananya Jahanara Kabir “Oye DJ, tírame la música” (Hey, DJ, throw me some music) sings Cuban-born New York resident Cucu Diamantes on her fi rst album, Cuculand (Wrasse Records, 2010). As the song, “Still in Love,” reveals, “este Moreno me miró que yo no pude contener” (the way this dark-haired man was looking at me, I just couldn ’ t control myself). The tale of attraction between the Hispanic “I” and her Moreno unfolds within a recognizably Latin soundscape – until about halfway through the song, when another beat begins pushing its way through the polyrhythmic template. Faint at fi rst, it reveals itself to the South Asian listening ear as the sounds of the dhol b e a t i n g out a Punjabi bhangra rhythm (the eight-beat kaharwa taal ). In confi rmation, the song ’ s coda has Diamantes repeating, till fade-out, in Hindi, “tu mera pyara hai” (you are my beloved one). The song ’ s signifi cance mutates from a transnational Cuban ’ s electronic-accented experiment on traditional salsa to a broader experi- mentation with other global dance sounds originating in diaspora; the Moreno this Morena seeks seems to be a South Asian rather than a fellow Latin lover. The all- powerful DJ is both muse and conduit for the coming together of these diverse beats, and peoples, on a dance fl oor replete with possibilities of unpredictable, even transgressive cultural encounters. Music and dance are multiply transnationalized, although without losing the glocal signifi cance of a Cuban singer in New York interpreting her musical heritage, which now goes by the universally acknowledged name of “salsa.” In their song “Arroz con salsa” (rice with salsa), Japan ’ s Orquesta de la Luz (La Aventura , RTL International, 1994) declare that “salsa no tiene fronteras” (salsa has no frontiers). -

Entangled Mobilities in the Transnational Salsa Circuit

Entangled Mobilities in the Transnational Salsa Circuit With attention to the transnational dance world of salsa, this book explores the circulation of people, imaginaries, dance movements, conventions and affects from a transnational perspective. Through interviews and ethnographic, multi-sited research in several European cities and Havana, the author draws on the notion of “entangled mobilities” to show how the intimate gendered and ethnicised moves on the dance floor relate to the cross-border mobility of salsa dance professionals and their students. A combination of research on migration and mobility with studies of music and dance, Entangled Mobilities in the Transnational Salsa Circuit contributes to the fields of transnationalism, mobility and dance studies, thus pro- viding a deeper theoretical and empirical understanding of gendered and racialised transnational phenomena. As such it will appeal to scholars across the social sci- ences with interests in migration, cultural studies and gender studies. Joanna Menet is a post-doctoral researcher at the Laboratory for the Study of Social Processes at the University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. The Feminist Imagination – Europe and Beyond Series Editors: Kathy Davis Senior Research Fellow, Vrije University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Mary Evans Visiting Professor, Gender Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science, UK With a specific focus on the notion of “cultural translation” and “travelling theory”, this series operates on the assumption that ideas are shaped by the contexts in which they emerge, as well as by the ways that they “travel” across borders and are received and re-articulated in new contexts. In demon- strating the complexity of the differences (and similarities) in feminist thought throughout Europe and between Europe and other parts of the world, the books in this series highlight the ways in which intellectual and political tradi- tions, often read as homogeneous, are more often heterogeneous. -

The Dynamics of Salsiology in Comtemporary Germany

THE DYNAMICS OF SALSIOLOGY IN CONTEMPORARY GERMANY: RECONSTRUCTING GERMAN CULTURAL IDENTITY THROUGH SALSA MUSIC AND DANCE Eddy Magaliel Enríquez Arana A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2007 Committee: Dr. Christina Guenther, Advisor Dr. Francisco Cabanillas, Advisor Dr. Valeria Grinberg Pla Dr. Geoffrey Howes © 2006 Eddy M. Enríquez Arana All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Christina Guenther, Advisor Dr. Francisco Cabanillas, Advisor This thesis explores the significance of the consumption of salsa music and dance in the Federal Republic of Germany and its impact on the construction and reconstruction of German and Latin American cultural identity. The discipline of cultural studies has much to learn from the Latin American presence in and their contributions to the establishment of the salsa institution in the Federal Republic. The thesis discusses the level of German involvement in the creation of a transnational music and dance culture traditionally associated with the Spanish-speaking world exclusively. iv To all my friends, peers and family who support me in my love for the German language and salsa music. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Ernesto Delgado of the Romance Languages Department for guiding and encouraging me in the conceptualization of the topic of this writing project; to Dr. Christina Guenther of the German section whose untiring and superb academic counseling oriented not only my scholarly development but also my skills as a writer, and instilled in me confidence and drive to excel in the study of cultures and languages; to Dr. -

“Latinizing” Your School Jazz Ensemble

“LATINIZING” YOUR SCHOOL JAZZ ENSEMBLE: PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS FOR ACHIEVING AN AUTHENTIC LATIN SOUND Michele Fernandez Denlinger Clinician Also featuring : The ‘’Caliente’’ Rhythm Section Mr. Jose Antonio Diaz, Director December 14, 2016 The Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic Chicago, Ill Playing and teaching the various forms of Latin music should not be viewed as an enigmatic challenge, although this undertaking is often described as such by music instructors everywhere. It is actually quite simple if one has access to the right concepts and patterns. During my years as a high school director I had the opportunity (and necessity) to observe and develop rehearsal techniques that allowed the jazz ensemble at Miami High to achieve the authentic sound that my students so much enjoyed sharing through many venues. However, it was only after my later experiences as a clinician, conference speaker and adjudicator that I actually made an attempt to collate and organize the principles and techniques I (sometimes unconsciously) applied with my students throughout my time as a director. This handout contains some basic principles and rehearsal suggestions that I hope will help any director/student unfamiliar with some of the major styles in this genre (and perhaps those a bit more familiar as well) to begin to teach and explore this infectious brand of music with more vigor and authenticity. Most of all: Have a great time; “Latin” music is truly a blast to play and teach! Michele *Questions/assistance regarding any material in this presentation will be promptly (and gladly) answered. Please refer to Section VII: Clinician BIO for contact info. -

Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UT Digital Repository The Report committee for Anna Monroe Teague Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: ___________________________________ John Turci-Escobar, Supervisor ___________________________________ Robin Moore Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music by Anna Monroe Teague, B.M. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May, 2015 Abstract Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music Anna Monroe Teague, M.Music The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 SUPERVISOR: John Turci-Escobar There are many statements from members of the salsa community (including scholars, musicians, and dancers) that mention the presence, gaining, or waning of metaphorical rhythmic energy. Since many salsa sources employ ethnomusicological, biographical, or performance approaches, however, any text briefly mentioning musical energy would not require validation for energetic claims. Adopting a music-theoretical approach, this report focuses on how the rhythm section contributes to energy perceptions. Syncopation—or metrical dissonance—underlies metaphorical energy in salsa. This syncopation appears in individual rhythmic patterns and layered polyrhythms called rhythmic profiles, which correspond to energy-level associations with particular instruments and formal sections. Additionally, rhythmic changes on the larger formal iii scale as well as on a smaller motivic scale can account for the perception of changes in energy levels. This report presents a method for analyzing metrical dissonance in Nuyorican salsa, after reviewing the relevant theoretical tools by Harald Krebs and Yonatan Malin and surveying the core features of this subgenre. -

With a Focus on Cuban Salsa (Casino) Melissa Cobblah Gutierrez

)ORULGD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\/LEUDULHV 2019 Understanding my Heritage Through the Deconstruction of Social Dance: With a Focus on Cuban Salsa (Casino) Melissa Cobblah Gutierrez Follow this and additional works at DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS UNDERSTANDING MY HERITAGE THROUGH THE DECONSTRUCTION OF SOCIAL DANCE: WITH A FOCUS ON CUBAN SALSA (CASINO) By MELISSA COBBLAH GUTIERREZ A Thesis submitted to the School of Dance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Spring, 2019 1 In its historical context, casino is a partner dance form that originated in the 1950’s in Cuba. It started to be practiced in recreational societies, clubs and ballrooms also known as casinos. Cubans attended the events held in these locations mainly to get away from their daily routine, have fun and be able to enjoy and dance to the national and latest international music played by famous musical groups. El Club Casino Deportivo is the location where casino first began to gain recognition as a new dance style. People started to frequently use the term of dancing in a rueda (which means wheel/dancing in a circle) like it’s done at the casino, which eventually is how the name got stuck by saying “Let’s do the rueda of casino”. The evolution of this form has been molded throughout time by the influence and emergence of several dance styles in Cuba, which have contributed significantly to the Cuban culture. These dance forms include la Contradanza, la Danza, el Danzón, el Danzonete, el Chachachá, el Son and lastly el Casino. -

The Influence of Nigerian Bata Dance on Cuban Salsa by Olorunjuwon

The influence of Nigerian Bata Dance on Cuban Salsa BY Olorunjuwon, Emmanuel Oloruntoba (MATRIC NO: RUN06-07/507) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE ARTS, SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES, REDEEMER’S UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTERS OF ARTS (M.A) IN THEATRE ARTS JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATION I certify that this project/long essay titled “THE INFLUENCE OF NIGERIAN BATA DANCE ON CUBAN SALSA” is an original work of mine and that it has not been submitted elsewhere for any degree award or certification. OLORUNJUWON EMMANUEL OLORUNTOBA (RUN 06-07/507) …………………………………….. CERTIFICATION I certify that this long essay was carried out by Olorunjuwon Emmanuel Oloruntoba with matriculation number RUN 06-07/507 of the Department Of Theatre Arts, Redeemer‟s University, Osun State. ------------------------------------ ---------------------------- Supervisor Date Dr. John Iwuh ……………………………… …………………………… Head of Department Date Prof. Ahmed Yerima ……………………… …………………… External Examiner Date Prof. Ojo Bakare DEDICATION I dedicate this project to God Almighty for giving me the strength and wisdom to carry out this research. My parents Mr. and Mrs. S.K Oloruntoba and my siblings Bamidele Oloruntoba, Christiana Oloruntoba and Dr. Ife Oloruntoba .My Mentor and guardian Prof. Ahmed Yerima. God bless you all. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To God almighty my strength, wisdom, creativity, rhythm and flexibility I am most grateful to you. I must thank the Head of Department, Prof Ahmed Yerima who has been a father to me. You were there for me and cared for me like your own biological son. You gave me shelter, clothes and you fed me. You never stopped making sense out of my nonsense and you encouraged me to write while others were sleeping. -

Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music

The Report committee for Anna Monroe Teague Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: ___________________________________ John Turci-Escobar, Supervisor ___________________________________ Robin Moore Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music by Anna Monroe Teague, B.M. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May, 2015 Abstract Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music Anna Monroe Teague, M.Music The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 SUPERVISOR: John Turci-Escobar There are many statements from members of the salsa community (including scholars, musicians, and dancers) that mention the presence, gaining, or waning of metaphorical rhythmic energy. Since many salsa sources employ ethnomusicological, biographical, or performance approaches, however, any text briefly mentioning musical energy would not require validation for energetic claims. Adopting a music-theoretical approach, this report focuses on how the rhythm section contributes to energy perceptions. Syncopation—or metrical dissonance—underlies metaphorical energy in salsa. This syncopation appears in individual rhythmic patterns and layered polyrhythms called rhythmic profiles, which correspond to energy-level associations with particular instruments and formal sections. Additionally, rhythmic changes on the larger formal iii scale as well as on a smaller motivic scale can account for the perception of changes in energy levels. This report presents a method for analyzing metrical dissonance in Nuyorican salsa, after reviewing the relevant theoretical tools by Harald Krebs and Yonatan Malin and surveying the core features of this subgenre.