Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

Groove in Cuban Dance Music: an Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis How to cite: Poole, Adrian Ian (2013). Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ef02 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk \ 1f'1f r ' \ I \' '. \ Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Adrian Ian Poole esc MA Department of Music The Open University Submitted for examination towards the award of Doctor of Philosophy on 3 September 2012 Dntc \.?~ ,Sllbm.~'·\\(~·' I ~-'-(F~\:ln'lbCt i( I) D Qt C 0'1 f\;V·J 0 1('\: 7 M (~) 2 013 f1I~ w -;:~ ~ - 4 JUN 2013 ~ Q.. (:. The Library \ 7<{)0. en ~e'1l poo DONATION CO)"l.SlALt CAhon C()F) Iiiiii , III Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Abstract The rhythmic feel or 'groove' of Cuban dance music is typically characterised by a dynamic rhythmic energy, drive and sense of forward motion that, for those attuned, has the ability to produce heightened emotional responses and evoke engagement and participation through physical movement and dance. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

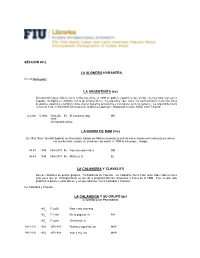

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Cuban Music Teaching Unit

Thesis Advisor: Frank Martignetti THE MUSIC AND DANCE OF CUBA: by Melissa Salguero Music Education Program Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Elementary Education in the School of Education University of Bridgeport 2015 © 2015 by Melissa Salguero Salguero 2 Abstract (Table of Contents) This unit is designed for 5th grade students. There are 7 lessons in this unit. Concept areas of rhythm, melody, form, and timbre are used throughout the unit. Skills developed over the 7 lessons are singing, moving, listening, playing instruments, reading/writing music notation, and creating original music. Lesson plans are intended for class periods of approximately 45-50 minutes. Teachers will need to adapt the lessons to fit their school’s resources and the particular needs of their students. This unit focuses on two distinct genres of Cuban music: Son and Danzón. Through a variety of activities students will learn the distinct sound, form, dance, rhythms and instrumentation that help define these two genres. Students will also learn about how historical events have shaped Cuban music. Salguero 3 Table of Contents: Abstract……………………………………………..…………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………….……………………………4 Research…………………………………………..……………………………5 The Cuban Musical Heritage……………….……………………………5 The Discovery of Cuba…….……………………………………………..5 Indigenous Music…...…………………………………………………….6 European Influences……………………………………………….……..6 African Influences………………………………………………………...7 Historical Influences……………………….……………………………..7 -

Beyond Salsa Piano the Cuban Timba Piano Revolution

BEYOND SALSA PIANO THE CUBAN TIMBA PIANO REVOLUTION VOLUME 6 • Iván “Melón” Lewis, Pt. 1 NOTE FOR NOTE TRANSCRIPTIONS by Kevin Moore photography by Tom Ehrlich cover photo subject: Iván “Melón” Lewis audio and video companion products available at www.timba.com/piano 1 REVISION 1.0 ©2010 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1450545602 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 9781450545600 www.timba.com/piano www.timba.com/audio www.timba.com/users/7 www.beyondsalsapiano.com [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Series ...................................................................................................................... 5 How the Series is Organized and Sold ................................................................................................ 5 Book ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Audio .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Video .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Series Overview ................................................................................................................................. -

Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and Style

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 1998 Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and style Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/318 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CHAPTER Srx Improvisation in Latin Dance Music: History and Style PETER MANUEL Latin dance music constitutes one of the most dynamic and sophisticated urban popular music traditions in the Americas. Improvisation plays an important role in this set of genres, and its styles are sufficiently distinctive, complex, and internally significant as to merit book-length treatment along the lines of Paul Berliner's volume Thinking in Jazz (1994 ). To date, however, the subject of Latin improvisation has received only marginal and cursory analytical treat ment, primarily in recent pedagogical guidebooks and videos. 1 While a single chijpter such as this can hardly do justice to the subject, an attempt will be made here to sketch some aspects of the historical development of Latin im provisational styles, to outline the sorts of improvisation occurring in main stream contemporary Latin music, and to take a more focused look at improvi sational styles of one representative instrument, the piano. An ultimate and only partially realized goal in this study is to hypothesize a unified, coherent aesthetic of Latin improvisation in general. -

Samples Can Be Auditioned At

No pianist has played on more records that all of postrevolutionary Cuba sang along with than Pupy. And at the same time, he's a direct link to that golden age of Arsenio and Chappotín. Ned Sublette author of Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo El modo de interpretar de Pupy Pedroso constituye el crossover entre la música bailable contemporanea cubana y los esquemas tradicionales heredados de los grandes pianistas soneros de los cincuentas, en particular, de su padre, Nené, quien fuera una de las luminarias de la época. Su estilo inovador, su talento para componer y orquestar y su sagacidad para lograr la preferencia pública en un país tan competitivo como Cuba, lo situan en uno de los lugares mas destacados del ambiente musical de los últimos cuarenta anos. Definitivamente Pupy, junto a José Luis “Changuito” Quintana y Juan Formell, forma parte del nucleo generador del sonido Van Van, que por tanto tiempo ha satisfecho las exigencias de los “casineros” mas puristas. Juan de Marcos composer, tresero, leader of The Afro‐Cuban All‐Stars Pupy, es poseedor de un estilo peculiar a la hora de tocar el piano, tumbaos de gran fuerza cargados de un estilo sonero indiscutible hacen de Pupy uno de los pianistas de Son mas importantes de los últimos años.” Adalberto Álvarez pianist, composer, founder of Son 14 and Adalberto Álvarez y su Son Indiscutiblemente César, Pupy, Pedroso es uno de los grandes pianistas de la música cubana de todos los tiempos. Su nombre puede ocupar un merecido lugar junto al de Luis ‘Lilí’ Martínez Griñán o Antonio María Romeu, pues al igual que ellos hicieron anteriormente, él también transformó la sonoridad del piano dentro de las proyecciones estéticas por donde cursaba la más auténtica cubanía. -

Cubaneo in Latin Piano: a Parametric Approach to Gesture, Texture, and Motivic Variation Orlando Enrique Fiol University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Cubaneo In Latin Piano: A Parametric Approach To Gesture, Texture, And Motivic Variation Orlando Enrique Fiol University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Fiol, Orlando Enrique, "Cubaneo In Latin Piano: A Parametric Approach To Gesture, Texture, And Motivic Variation" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3112. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3112 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3112 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cubaneo In Latin Piano: A Parametric Approach To Gesture, Texture, And Motivic Variation Abstract ABSTRACT CUBANEO IN LATIN PIANO: A PARAMETRIC APPROACH TO GESTURE, TEXTURE, AND MOTIVIC VARIATION COPYRIGHT Orlando Enrique Fiol 2018 Dr. Carol A. Muller Over the past century of recorded evidence, Cuban popular music has undergone great stylistic changes, especially regarding the piano tumbao. Hybridity in the Cuban/Latin context has taken place on different levels to varying extents involving instruments, genres, melody, harmony, rhythm, and musical structures. This hybridity has involved melding, fusing, borrowing, repurposing, adopting, adapting, and substituting. But quantifying and pinpointing these processes has been difficult because each variable or parameter embodies a history and a walking archive of sonic aesthetics. In an attempt to classify and quantify precise parameters involved in hybridity, this dissertation presents a paradigmatic model, organizing music into vocabularies, repertories, and abstract procedures. Cuba's pianistic vocabularies are used very interactively, depending on genre, composite ensemble texture, vocal timbre, performing venue, and personal taste. -

Tres Danzas Cubanas by Alejandro García Caturla: a Transcription for Wind Orchestra with Accompanying Biographical Sketch and Transcription Method

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2017 Tres Danzas Cubanas by Alejandro García Caturla: A Transcription for Wind Orchestra with Accompanying Biographical Sketch and Transcription Method Darrell Brown University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Latin American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Repository Citation Brown, Darrell, "Tres Danzas Cubanas by Alejandro García Caturla: A Transcription for Wind Orchestra with Accompanying Biographical Sketch and Transcription Method" (2017). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2951. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10985788 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRES DANZAS CUBANAS BY ALEJANDRO GARCÍA CATURLA: A TRANSCRIPTION FOR WIND ORCHESTRA WITH ACCOMPANYING -

The Saxophone in Puerto Rico: History and Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The aS xophone in Puerto Rico: History and Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works Marcos David Colón-Martín Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Colón-Martín, Marcos David, "The aS xophone in Puerto Rico: History and Annotated Bibliography of Selected Works" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1214. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1214 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SAXOPHONE IN PUERTO RICO: HISTORY AND ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Musical Arts in The School of Music by Marcos David Colón Martín B.M., Conservatorio de Música de Puerto Rico, 2007 M.M., University of New Mexico, 2009 May 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of my graduate committee for their patience and genuine help through this process. I am indebted in particular to my major advisor, Griffin Campbell, for his guidance in the writing of this monograph and his mentoring in my musical learning. His great artistry and musical knowledge made every lesson a new experience, and for this I am glad I came to LSU. -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

Son Patin Linear Style Salsa, Basics Isolation (On1) Elements of Rumba

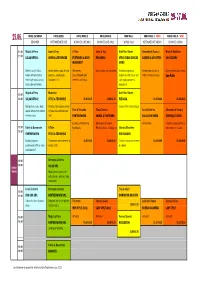

25.06. HOTEL KATARINA HOTEL EDEN HOTEL PARK 1 HOTEL PARK 2 MMC HALL ADRIS HALL 1 - NEW! ADRIS HALL 2 - NEW! BEGINNER INTERMMEDIATE LINE ADVANCED LINE (ON1) ADVANCED LINE (ON2) WORLD SALA INTERMMEDIATE CUBAN ADVANCED CUBAN 11:00 Matjaž & Petra Jorjet & Troy U-Tribe Jorjet & Troy Ariel Rios Robert Alexander & Yunaisy Mario & Madeline 11:50 SALSA INTRO 1 SHINES & TECHNIQUE FOOTWORK & BODY PACHANGA AFRO-CUBAN DANCES DANZON & SON INTRO SON CUBANO MOVEMENT INTRO What is salsa? Salsa Simple shines, body & hand Afro shines. Basics steps and variations.History background, Introductory classes in Clave, rhythm, basic steps history. Introduction in postures, simple body Salsa footwork with importance for dance and Cuban national dances. Son Patin linear style salsa, basics isolation (On1) elements of rumba. style, body posture & steps, demonstration. movement Matjaž & Petra Mambata Ariel Rios Robert 12:00 12:50 SALSA INTRO 2 STYLE & TECHNIQUE 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 ELEGGUA 11.00-12.20 11.00-12.20 Bod posture, cross body Fluidity, style & body control Dance of the orisha Elegua lead & simple turn pattern in linear salsa partnerwork Fran & Veronika Tito & Tamara Israel Gutierrez Alexander & Yunaisy in linear salsa (On1) PARTNERWORK SHINES & FOOTWORK SALSA CON TIMBA TECHNIQUE WORK Leading and following Working on technique. Partnerwork Footwork, body posture & 13:00 Fabris & Rosemarie U-Tribe techniques PR style shines - building up Mario & Madeline movements in Casino 13:50 PARTNERWORK STYLE & TECHNIQUE from simple to advanced SON CUBANO Building up your Partnerwork with elements of 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 Tornillos variations for men 12.40-14.00 12.40-14.00 partnerwork.