The Dynamics of Salsiology in Comtemporary Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paperboys Workshops 092515

The Paperboys Workshops Celtic Fiddle Kalissa Landa teaches this hands-on workshop covering Irish, Scottish, Cape Breton and Ottawa Valley styles. The class covers bow technique, ornamentation, lilts, slurs, slides etc. and includes reels, jigs, polkas, airs and strathspeys. Kalissa has been playing fiddle since before she could walk, and dedicates much of her time to teaching both children and adults. She runs the fiddle program at the prestigious Vancouver Academy of Music. For beginners, intermediate, or advanced fiddlers. Celtic Flute/Whistle Paperboys flute/whistle player Geoffrey Kelly will have you playing a jig or a reel by the end of the class. While using the framework of the melody, you will learn many of the ornaments used in Celtic music, including slides, rolls, trills, hammers etc. We will also look at some minor melody variations, and where to use them in order to enhance the basic melody. Geoffrey is a founding member of Spirit of the West, a four-year member of the Irish Rovers, and the longest serving Paperboy. Geoffrey has composed many of the Paperboys’ instrumentals. Latin Music Overview In this workshop, the Paperboys demonstrate different styles of Latin Music, stopping to chat about them and break down their components. It's a Latin Music 101 for students to learn about the different kinds of genres throughout Latin America, including but not limited to Salsa, Merengue, Mexican Folk Music, Son Jarocho, Cumbia, Joropo, Norteña, Son Cubano, Samba, and Soca. This is more of a presentation/demonstration, and students don't need instruments. Latin Percussion Percussionist/Drummer Sam Esecson teaches this hands-on workshop, during which he breaks down the different kinds of percussion in Latin music. -

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

UC Riverside Diagonal: an Ibero-American Music Review

UC Riverside Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review Title Goldberg, K. Meira, Walter Aaron Clark, and Antoni Pizà, eds. "Transatlantic Malagueñas and Zapateados in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Natives, Africans, Roma." Newscastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5dq9z93m Journal Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review, 5(2) ISSN 2470-4199 Author Nocilli, Cecelia Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/D85247375 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Review Goldberg, K. Meira, Walter Aaron Clark, and Antoni Pizà, eds. Transatlantic Malagueñas and Zapateados in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Natives, Africans, Roma. Newscastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. CECILIA NOCILLI Universidad de Granada Beyond Dance: Analysis, Historiography, and Redefinitions The anthology Transatlantic Malagueñas and Zapateados in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Natives, Africans, Roma opens with a suggestive image of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in La Malagueña of 1921, which synthesizes the identity of the publication: an exploration of the transatlantic journeys of Spanish dance and its exotic fascination. The image thus manifests the opposition between the maja and the manolo (tough girl and tough guy), as between the Andalusian woman and the bullfighter. In their introduction, Meira Goldberg, Walter Aaron Clark and Antoni Pizà highlight the relationship between this anthology and an earlier volume on the fandango as a clearly mestizo, or hybridized, dance form blending African, European, and American influences: The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies (Música Oral del Sur vol. -

Mark III Owners Manual

MESA-BOOGIE MARK III OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS MESA ENGINEERING CONGRATULATIONS! You've just become the proud owner of the world's finest guitar amplifier. When people come up to compliment you on your tone, you can smile knowingly ... and hopefully you'll tell them a little about us! This amplifier has been designed, refined and constructed to deliver maximum musical performance of any style, in any situation. And in order to live up to that tall promise, the controls must be very powerful and sophisticated. But don't worry! Just by following our sample settings, you'll be getting great sounds immediately. And as you gain more familiarity with the Boogie's controls, it will provide you with much greater depth and more lasting satisfaction from your music. THREE MODES For approximately twelve years, the evolution of the guitar amplifier has largely been pioneered by MESA-Boogie. The Original Mark I Boogie was the first amplifier to offer successful lead enhancement. Then the Mark II Boogie was the first amplifier to introduce footswitching between lead and rhythm. Now your new Mark III offers three footswitchable modes of operation: Rhythm 1, Rhythm 2 and Lead. Rhythm 1 is primarily for playing bright and sparkling clean (although a little crunch is available by running the Volume at 10). You might think of Rhythm 1 as "the Fender mode”. Rhythm 2 is mainly for crunch chords, chunking metal patterns and some blues (but low settings of the Volume 1 will produce an alternate clean sound that is very fat and warm). Think of Rhythm 2 as "the Marshall mode". -

Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month! for People Who Love Books And

Calendar of Events September 2016 For People Who Love Books and Enjoy Experiences That Bring Books to Life. “This journey has always been about reaching your own other shore, no matter what it is, and that dream continues.” Diana Nyad The Palm Beach County Library System is proud to present the third annual Book Life series, a month of activities and experiences designed for those who love to read. This year, Celebrate Hispanic we have selected two books exploring journeys; the literal and figurative, the personal and shared, and their power to define Heritage Month! or redefine all who proceed along the various emerging paths. The featured books for Book Life 2016 are: By: Maribel de Jesús • “Carrying Albert Home: The Somewhat True Story Multicultural Outreach Services Librarian of a Man, His Wife, and Her Alligator,” by Homer For the eleventh consecutive year the Palm Beach County Library System Hickham celebrates our community’s cultural diversity, the beautiful traditions of • “Find a Way,” by Diana Nyad Latin American countries, and the important contributions Hispanics have Discover the reading selections and enjoy a total of 11 made to American society. educational, engaging experiences inspired by the books. The national commemoration of Hispanic Heritage Month began with a Activities, events and book discussions will be held at various week-long observance, started in 1968 by President Lyndon B. Johnson. library branches and community locations throughout the Twenty years later, President Ronald Reagan expanded the observation month of September. to September 15 - October 15, a month-long period which includes several This series is made possible through the generous support of Latin American countries’ anniversaries of independence. -

University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's Theses UARC.0666

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833tht No online items Finding Aid for the University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses UARC.0666 Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 1998 June; revised by Katharine A. Lawrie; 2013 October. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 August 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections UARC.0666 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses Creator: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Identifier/Call Number: UARC.0666 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet(30 cartons) Date (inclusive): 1958-1994 Abstract: Record Series 666 contains Master's theses generated within the UCLA Dance Department between 1958 and 1988. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. All requests for permission to publish or quote must be submitted in writing to the UCLA University Archivist. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses (University Archives Record Series 666). UCLA Library Special Collections, University Archives, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 Application of Comcast Corporation, General Electric Company

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 Application of Comcast Corporation, ) General Electric Company and NBC ) Universal, Inc., for Consent to Assign ) MB Docket No. 10-56 Licenses or Transfer Control of ) Licenses ) COMMENTS AND MERGER CONDITIONS PROPOSED BY ALLIANCE FOR COMMUNICATIONS DEMOCRACY James N. Horwood Gloria Tristani Spiegel & McDiarmid LLP 1333 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 879-4000 June 21, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PEG PROGRAMMING IS ESSENTIAL TO PRESERVING LOCALISM AND DIVERSITY ON BEHALF OF THE COMMUNITY, IS VALUED BY VIEWERS, AND MERITS PROTECTION IN COMMISSION ACTION ON THE COMCAST-NBCU TRANSACTION .2 II. COMCAST CONCEDES THE RELEVANCE OF AND NEED FOR IMPOSING PEG-RELATED CONDITIONS ON THE TRANSFER, BUT THE PEG COMMITMENTS COMCAST PROPOSES ARE INADEQUATE 5 A. PEG Merger Condition No.1: As a condition ofthe Comcast NBCU merger, Comcast should be required to make all PEG channels on all ofits cable systems universally available on the basic service tier, in the same format as local broadcast channels, unless the local government specifically agrees otherwise 8 B. PEG Merger Condition No.2: As a merger condition, the Commission should protect PEG channel positions .,.,.,.. ., 10 C. PEG Merger Condition No.3: As a merger condition, the Commission should prohibit discrimination against PEG channels, and ensure that PEG channels will have the same features and functionality, and the same signal quality, as that provided to local broadcast channels .,., ., ..,.,.,.,..,., ., ., .. .,11 D. PEG Merger Condition No.4: As a merger condition, the Commission should require that PEG-related conditions apply to public access, and that all PEG programming is easily accessed on menus and easily and non-discriminatorily accessible on all Comcast platforms ., 12 CONCLUSION 13 EXHIBIT 1 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Mixology Shaken Or Stirred? Olive Or Onion? Martini Cocktail Sipping Is an Art Developed Over Time

Vol: XXXVI Wednesday, April 3, 2002 INSIDI: THIS WI;I;K ^ PHOTO BY SOFIA PANNO Various dancers from all the participating tribes and nations in this event; Blood Tribe, Peigan Nation and Blackfoot Nation performing a dance together. LCC celebrates flboriginal Ruiareness Day BY SOFIA PANNO president. the weather," said Gretta Old Shoes, Endeawour Staff The Rocky Lake Singers and Blood Tribe member and first-year Drummers entertained the crowd student at LCC. gathered around Centre Core with their Events such as this help both aboriginal As Lethbridge Community College traditional singing and drum playing, as and non-aboriginal communities better First Nations and Aboriginal Awareness did the exhibition dancers with their understand each other. Day commenced, the beat of the drums unique choreography. "It's very heart-warming to see students and the echoes from the singing flowed According to native peoples' culture from LCC take in our free event because through LCC's hallways on March 27, and beliefs passed down from one that's our main purpose, to share our 2002. generation to the next, song and dance is aboriginal culture," said David. "Our theme was building used to honour various members of a LCC First Nations Club members relationships," said Salene David, First tribe. Some songs honour the warriors indicate that awareness of native peoples' Nations Club member/volunteer. while others, the women of the tribe. current needs at LCC is a necessary step, According to the club's president Bill Canku Ota, an online newsletter in understanding them and their culture. Healy, the LGC First Nations Club Piita celebrating Native America explains the "We [the native peoples] have been Pawanii Learning Society is responsible Midewiwin Code for Long Life and here since the college has been opened for the organizing of this year's event. -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

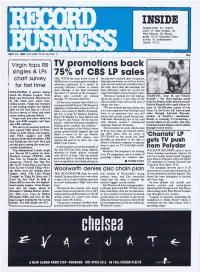

Record-Business-1982

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums, 19; Airplay guide, 15-15; Quarterly Chart survey, 12; Independent Labels, 12/13. April 12, 1982VOLUME FIVE Number 3 65p Virgin tops RBTV promotions back singles & LPs 75% of CBS LP sales chart survey CBS, WITH the most active roster ofthe industry's national chart was gained, MOR artists, is increasingly resorting toalthough promotion on such an intense television promotion asa means ofscale was not underway anywhere else at for first time securing sufficient volume to ensurethe time. Since then the campaign has chart placings. It has been estimatedbeen efficiently rolled out to give the FOLLOWING A quarter during that about 75 percent of the company'ssinger her highest chart placing to date. which the Human League, Toni albumsalescurrentlyarecoming Television backing for the IglesiasTIGHTFIT, keepfitand Felicity Basil and Orchestral Manoeuvres through TV -boosted repertoire. album has given it a new lease of lifeKendall - the chart -topping group In The Dark were major best- after an earlier chart entry at the time offrom the Zomba stable present actress selling artists, Virgin has emerged Of the seven releases with which it is scoring in the RB Top 60, CBS has givenrelease last year. Felicity Kendall with a gold album for as the leading singles and albums "We are certainly getting volume, butsales of 200,000 -plus copies of her label for the first time in a Record significant smallscreen support to five of them, Love Songs by Barbra Streisand,it is a very expensive way of doing it andShape Up And Dance LP, sold on mail Business survey of chart and sales there is no guarantee that you willorderthroughLifestyleRecords, action during January -March.