Aphrodite's Entry Into Epic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period. -

Secreted Desires: the Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde

ii Secreted Desires The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde ii iii Secreted Desires The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde Michael Matthew Kaylor Brno, Czech Republic: Masaryk University, 2006 ii Print Version — Copyright 2006 — Michael Matthew Kaylor First published in 2006 by Masaryk University ISBN: 80-210-4126-9 Electronic Version — Copyright 2006 — Michael Matthew Kaylor First published in 2006 by the Author Notes Regarding the Electronic Version Availability: The electronic version of this volume is available for free download — courtesy of the author — at http://www.mmkaylor.com. Open Access: The electronic version is provided as open access, hence is free to read, download, redistribute, include in databases, and otherwise use — subject only to the condition that the original authorship be properly attributed. The author retains copyright for the print and electronic versions: Masaryk University retains a contract for the print version. Citing This Volume: Since the electronic version was prepared for the purposes of the printing press, it is identical to the printed version in every textual aspect (except for this page). For this reason, please provide all citations as if quoting from the printed version: • APA Citation Style: Kaylor, M. M. (2006). Secreted desires: The major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde . Brno, CZ: Masaryk University Press. • Chicago and Turabian Citation Styles: Kaylor, Michael M. 2006. Secreted desires: The major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde . Brno, CZ: Masaryk University Press. • MLA Citation Style: Kaylor, Michael M. Secreted Desires: The Major Uranians: Hopkins, Pater and Wilde . Brno, CZ: Masaryk University Press, 2006. iii Die Knabenliebe sei so alt wie die Menschheit, und man könne daher sagen, sie liege in der Natur, ob sie gleich gegen die Natur sei. -

The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity

P1: ICD 9780521572019pre CUFX214/Budin 978 0 521 88090 9 November 12, 2007 19:38 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: ICD 9780521572019pre CUFX214/Budin 978 0 521 88090 9 November 12, 2007 19:38 THE MYTH OF SACRED PROSTITUTION IN ANTIQUITY In this study, Stephanie Lynn Budin demonstrates that sacred prostitution, the sale of a person’s body for sex in which some or all of the money earned wasdevoted to a deity or a temple, did not exist in the ancient world. Recon- sidering the evidence from the ancient Near East, the Greco-Roman texts, and the early Christian authors, Budin shows that the majority of sources that have traditionally been understood as pertaining to sacred prostitution actu- ally have nothing to do with this institution. The few texts that are usually invoked on this subject are, moreover, terribly misunderstood. Furthermore, contrary to many current hypotheses, the creation of the myth of sacred pros- titution has nothing to do with notions of accusation or the construction of a decadent, Oriental “Other.” Instead, the myth has come into being as aresult of more than 2,000 years of misinterpretations, false assumptions, and faulty methodology. The study of sacred prostitution is, effectively, a historiographical reckoning. Stephanie Lynn Budin received her Ph.D. in Ancient History from the Uni- versity of Pennsylvania with concentrations in Greece and the ancient Near East. She is the author of The Origin of Aphrodite (2003) and numerous arti- cles on ancient religion and iconography. She has delivered papers in Athens, Dublin, Jerusalem, London, Nicosia, Oldenburg, and Stockholm, as well as in various cities throughout the United States. -

VENUS: the DUAL GODDESS and the STAR GODDESS by Arielle Guttman

VENUS: THE DUAL GODDESS and THE STAR GODDESS by Arielle Guttman This article is an excerpt from Venus Star Rising: A New Cosmology for the 21st Century © 2010 VENUS Rules two astrological signs (Taurus and Libra) Has two birth myths and places Creates two complete pentagrams in eight years Is a Morning Star and an Evening Star Transits the Sun in pairs (2004 and 2012 most recent) The Dual Nature of Venus: Morning Star and Evening Star Two observations have led me to conclude that the Venus Star affects Earth and its inhabitants in much greater ways than anyone has yet comprehended. The myths and legends that have come down to us through the ages give Venus two faces - that of the Morning Star and the Evening Star - and the qualities ascribed to Venus in such stories seem correct when observing which star is operating in a person’s life based upon when they were born.i The myths point to Venus as both the goddess of love and of war. She does seem to have a firm grip on Earth and its inhabitants, cradling us in her star pattern, keeping humans between the states of love and war. Transcending this duality, so that we can reflect the love that is the core principle of Venus and the universe, is the major challenge currently faced by humanity. Accepting that Venus has a dual nature - that she is both a love goddess and a warrior goddess - acknowledges the holistic nature of Venus and of love itself. Although we may think of war more as a masculine phenomenon and love as associated with the feminine principle, the ancients saw Venus as female, whether lover (Evening Star) or warrior (Morning Star). -

William Manning the DOUBLE TRADITION of APHRODITE's

William Manning THE DOUBLE TRADITION OF APHRODITE'S BIRTH AND HER SEMITIC ORIGINS In contrast to modem religion, there was no "church" or religious dogma in the ancient world. No congress of Bishops met to decide what was acceptable doctrine and what was, by process of elimination, heresy. Matters of faith could be exceedingly complex and variable. The gods evolved over time and from place to place, dividing and diverg ing, so that many simultaneous beliefs were possible. Most students of Greek mythology are familiar with the "pairing" of certain gods and goddesses in the pantheon. Zeus is associated with his wife Hera, and Apollo with his sister Artemis, for example. It is believed that this reflects the introduction of male Sky Gods by Indo European invaders, which were allowed to co-exist with the Earth Mother Goddesses already worshipped by indigenous populations. Some scholars believe that Posiedon and Zeus are manifestations of the same Inda-European deity brought to the Greek mainland by succes sive waves of immigrants. Other aspects of mythological duality include the presence of apparently contrasting attributes within the same deity, and the allocation of opposing aspects of the same activity to more than one God. The example most often cited is Athena, Goddess of Wisdom. While she was patroness of culture and learning, she was always depicted in armor and championed the "positive" aspects of war such as courage and loyalty. The grouping of these attributes would seem strange to us today. Most Classics students will immediately point out that it is Ares who was recognized as the God of War. -

Mark Stanley Wheller

Christ as Ancestor Hero: Using Catherine Bell’s Ritual Framework to Analyze 1 Corinthians as an Ancestor Hero Association in First Century CE Roman Corinth by Mark Wheller A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Religious Studies University of Alberta © Mark Wheller, 2017 Abstract The Corinthian community members employed a Greco-Roman heroic model to graft their ancestral lineages, through the rite of baptism, to the genos Christ-hero. In doing so, the Corinthians constructed an elaborate ancestral lineage, linking their association locally through Christ to Corinth, and trans-locally through Moses to an imagined Ancient Israel. For the community, Christ’s death and resurrection aligned with the death and epiphanies of ancient heroes, as did his characteristics as a healer, protector, and oracle. Relatedly, the “Lord’s Meal,” as practiced by the Corinthians, was a hybrid ritual, as the association synthesized the meal with the already-existing heroic rites of theoxenia and enagezein. This ritualized meal allowed the Christ-hero followers to bring their hero closer to them, imbuing their oracular rituals of prophecy and speaking in tongues, as well as their protection rituals. In response to their hero, the Christ-hero members offered locks of their hair through hair-cutting and hair-offering rituals. Their funerary rites and ritualized meals nuanced and dominated other cultic aspects such as healing, oracles, offerings, baptism, and defixiones. Yet the Christ-hero did more than just focus worship for the community. In fact, it allowed a newly transplanted migrant population to construct a socio-political space within the polis, by restructuring their neighbourhood networks and claiming ownership and status within the greater Corinthian environment. -

The Gods of Olympus Olympian Gods

The Gods of Olympus Olympian Gods • Zeus • Hera • Poseidon • Hestia • Apollo • Demeter • Ares • Athena • Hermes • Aphrodite • Hephaestus • Artemis Hera Hera • Daughter of Cronus and Rhea • Perhaps an ancient nature goddess – One of the few not from Egypt (Hdts. ii.50) • Born in Argos or Samos • Patron of Sparta, Mycenae and Argos • Represented with veil, peacock and scepter Heraion at Argos Hera • Wife of Zeus – Honored by other gods but inferior to Zeus • Hieros Gamos • Goddess of marriage and childbirth • Mother of Ares, Hebe and Hephaestus • Mostly a foil to Zeus: – Jealous, argumentative. Hera and Zeus Hestia Hestia • Daughter of Cronus and Rhea • Goddess of the hearth (home fire) • Virgin goddess • Presides over all sacrifices • Home fire of the city in the Prytaneum Athena Athena • Daughter of Zeus and Metis (wisdom) – Tritogeneia; born near the river Triton – Or; born from the head • Goddess of the air – Glaucopis; the blue-eyed one – Athena, more than any other goddess, is the female representation of Zeus. Birth of Athena Pallas Athena • Most common epithet – Obscure origins, not a Greek word • Iconic connections with Ishtar and Syrian warrior goddesses – Pallas was a giant whom Athena killed and flayed using the skin to make her shield. Athena • Goddess of engineers, architects etc. – All of the technical aspects of civilization – Patron of the arts, both practical and aesthetic • Protector of the state and society – Supervisor of the laws and the assembly • Goddess of War; – As protector of the state – Grand Strategy Patron -

Catalogue of His Famous Collection the Bode Museum (Fig

THE SECOND GLANCE All Forms of Love Supported by Co-funded by In cooperation with In Collaboration with 1 All Forms of Love TABLE OF CONTENT 3 Survey of Labelled Objects 4 Introduction 7 Path 1 – In War and Love 12 Path 2 – Male Artists and Homosexuality 19 Path 3 – Art of Antiquity and Enlightened Collecting 22 Path 4 – Heroines of Virtue 28 Path 5 – Crossing Borders 32 Terminology 34 Suggested General Reading and Internet Sources 35 Imprint Cover: Giambologna (1529–1608) Mars gradivus, ca. 1580 © Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin / Jörg P. Anders. 2 All Forms of Love SURVEY OF LABELLED OBJECTS 1 IN LOVE AND WAR The first path analyses the represen tation of the 210 heroic soldier and the boundaries between 261 209 masculine prowess and bisexuality 211 208 Small Dome 213 212 214 216 215 258 219 2 218 221 217 257 222 220 MALE ARTISTS AND 223 256 246 225 Gobelin 224 Room 255 245 244 252 254 243 HOMOSEXUALITY 226 242 241 The second path deals with works made by male Great 236 250 240 Dome 249 239 homosexual artists or those close to this group 238 237 235 234 233 232 3 ART OF ANTIQUITY 141 AND ENLIGHTENED 106 139 107 Small Dome 108 COLLECTING 109 Male homosexual collectors are the focus of the third path 110 Basilika 134 111 114 113 Kamecke 132 125 4 Room 131 129 130 115 124 HEROINES Great Dome 128 123 122 OF VIRTUE 121 The fourth path concentrates on the representation of women’s intimacy and female-to-female sexual affection Entrance 5 CROSSING Small Dome BORDERS Access Crypt The fifth path introduces both historical characters and 072 interpretations of gender reassignment and gender ambiguity 073 038 3 THE SECOND GLANCE Exhibition 1: Introduction All Forms of Love 1 Zacharias Hegewald (1596–1639) Adam and Eve as Lovers, ca. -

Ebook Download Aphrodite Ebook, Epub

APHRODITE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Isabel Allende | 368 pages | 08 Aug 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007205165 | English | London, United Kingdom 7 Beautiful Facts About Aphrodite | HowStuffWorks The poet known as Homer calls Aphrodite the daughter of Zeus and Dione. She is also described as the daughter of Oceanus and Tethys both Titans. If Aphrodite is the cast-offspring of Uranus, she is of the same generation as Zeus' parents. If she is the daughter of the Titans, she is Zeus' cousin. Aphrodite was called Venus by the Romans -- as in the famous Venus de Milo statue. Mirror, of course -- she is the goddess of beauty. Also, the apple , which has lots of associations with love or beauty as in Sleeping Beauty and especially the golden apple. Aphrodite is associated with a magic girdle belt , the dove, myrrh and myrtle, the dolphin, and more. In the famous Botticelli painting, Aphrodite is seen rising from a clam shell. The story of the Trojan War begins with the story of the apple of discord, which naturally was made of gold:. Cancel Submit. Your feedback will be reviewed. Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio. What is the definition of Aphrodite? Browse aphelion. Test your vocabulary with our fun image quizzes. Image credits. Word of the Day vindicate. Read More. New Words medfluencer. Aphrodite's major symbols include myrtles , roses , doves , sparrows , and swans. The cult of Aphrodite was largely derived from that of the Phoenician goddess Astarte , a cognate of the East Semitic goddess Ishtar , whose cult was based on the Sumerian cult of Inanna. -

Aphrodite's Entry Into Epic

Aphrodite’s Entry into Epic by Brian Clark In Greek myth the face of the feminine becomes more defined; the warrior and strategic sides belong to Athena, the mothering and nurturing side rests with Demeter, while Artemis carries the wild and instinctual sides. While we will look at many stories involving Aphrodite perhaps we should start with her entry into epic to appreciate the difficulty her sexuality and erotic nature may have presented to a rising patriarchal and rationalistic society. In Homeric epic it is evident that Aphrodite’s erotic power to seduce the hero away from the battlefield is at great odds with the heroic nature of the warrior. Hence Aphrodite enters epic disempowered. Homer, aligned with the hero, portrays Aphrodite as the goddess who seduces the hero away from his tasks. Aphrodite’s name being linked with aphros or the sea-foam is a constant reminder of Hesiod’s version of her potent and chaotic birth. Homer, placing her lineage under Zeus, makes an interesting comment on changing social mores, placing Aphrodite’s erotic power under the divine order of Zeus. Sexual desire or ‘the lust that leads to disaster’, as well as the instincts of love and pleasure, are now placed in the dominion of the sky god Zeus. In the Homeric poem the Iliad Aphrodite is ridiculed and denigrated and also favours the Trojans, not the Greeks. Why is Aphrodite a threat to the Homeric poets? Her sphere is the bedroom, not the battlefield and her power seduces the hero. In the Iliad she rescues her son, Aeneas, and her protégé, Paris, from the battlefield. -

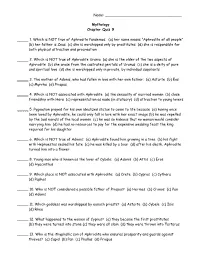

Mythology Chapter Quiz 9

Name: __________________________________ Mythology Chapter Quiz 9 _____ 1. Which is NOT true of Aphrodite Pandemos: (a) her name means “Aphrodite of all people” (b) her father is Zeus (c) she is worshipped only by prostitutes (d) she is responsible for both physical attraction and procreation _____ 2. Which is NOT true of Aphrodite Urania (a) she is the older of the two aspects of Aphrodite (b) she arose from the castrated genitals of Uranus (c) she is a deity of pure and spiritual love (d) she is worshipped only in private, by individual suppliants _____ 3. The mother of Adonis, who had fallen in love with her own father: (a) Astarte (b) Eos (c) Myrrha (d) Priapus _____ 4. Which is NOT associated with Aphrodite (a) the sexuality of married women (b) close friendship with Hera (c) representation as nude (in statuary) (d) attraction to young lovers _____ 5. Pygmalion prayed for his own idealized statue to come to life because (a) having once been loved by Aphrodite, he could only fall in love with her exact image (b) he was repelled by the bad morals of the local women (c) he was so hideous that no woman would consider marrying him (d) he had no resources to pay for the expensive wedding feast the king required for his daughter _____ 6. Which is NOT true of Adonis: (a) Aphrodite found him growing in a tree (b) his fight with Hephaestus sealed his fate (c) he was killed by a boar (d) after his death, Aphrodite turned him into a flower _____ 8. -

Radicalism, Rational Dissent, and Reform : the Pla- Tonised Interpretation of Psychological Androgyny and the Unsexed Mind in England in the Romantic Era

BIROn - Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Radicalism, rational dissent, and reform : the Pla- tonised interpretation of psychological androgyny and the unsexed mind in England in the Romantic era https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/44948/ Version: Citation: Russell, Victoria Fleur (2019) Radicalism, rational dissent, and reform : the Platonised interpretation of psychological androgyny and the unsexed mind in England in the Romantic era. [Thesis] (Unpub- lished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through BIROn is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Radicalism, Rational Dissent, and Reform: The Platonised Interpretation of Psychological Androgyny and the Unsexed Mind in England in the Romantic Era. Victoria Fleur Russell Department of History, Classics & Archaeology Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) September 2017 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Victoria Fleur Russell 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the Platonised concept of psychological androgyny that emerged on the radical margins of Rational Dissent in England between the 1790s and the 1840s. A legacy largely of the socio-political and religious impediments experienced by Rational Dissenters in particular and an offshoot of natural rights theorising, belief in the unsexed mind at this time appears more prevalent amongst radicals in England than elsewhere in Britain. Studied largely by scholars of Romanticism as an aesthetic concept associated with male Romantics, the influence of the unsexed mind as a notion of psycho-sexual equality in English radical discourse remains largely neglected in the historiography.