Australian Wood Chenonetta Jubata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvadori's Duck of New Guinea

Salvadori’s Duck of New Guinea J . K E A R When Phillips published the fourth volume of to the diving ducks and mergansers. Then his Natural History of the Ducks in 1926, he Mayr (1931a) was able to examine a dead noted that Salvadori’s Duck Salvadorina specimen and found that the sternum and (Anas) waigiuensis was ‘the last to be brought trachea of the male were, although smaller, to light and perhaps the most interesting of the similar to those of the Mallard Anas platy peculiar anatine birds of the world’. It was still rhynchos. As a result, Salvadori’s Duck was practically unknown in 1926; the first moved to the genus A nas. However, as recorded wild nest was not seen until 1959 (H. Niethammer (1952) and Kear (1972) later M. van Deusen, in litt.), and even today the pointed out, the trachea of the Torrent and species has been little studied. Blue Duck are also Anas-like, so that, on this The first specimen was called Salvadorina character, the genera M e rg a n e tta and waigiuensis in 1894 by the Hon. Walter Hymenolaimus could also be eliminated, and Rothschild and by Dr Ernst Hartert, his all three species put with the typical dabbling curator at the Zoological Museum at Tring. ducks. The name was to honour Count Tomasso The present author had already studied the Salvadori, the Italian taxonomist who Blue Duck in New Zealand (Kear, 1972), and specialized both in waterfowl and in the birds was lucky enough to be able to watch of Papua New Guinea. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

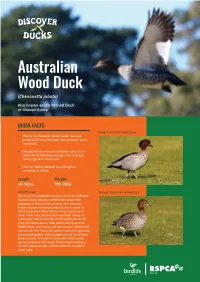

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta Jubata)

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta jubata) Also known as the ‘Maned Duck’ or ‘Maned Goose’ QUICK FACTS Male Australian Wood Duck • They are nicknamed ‘Maned Goose’ because people think they look more like miniature geese than ducks. • Wood Ducks love heavy rainfall because this is when the tastiest bugs emerge. They also love laying eggs after heavy rain. • They are better adapted to walking than swimming or diving. Length: Weight: 44–50cm 700–955g Identification: Female Australian Wood Duck The Australian Wood Ducks have earnt the nickname ‘Maned Goose’ because of their very goose-like appearance. The feathers around their neck and breast also give the impression of a lion’s mane. In flight, Australian Wood Ducks’ wings come out on show. Their wing tips are black and their wings are a pale grey with a white bar on the underside of the wing. Like many ducks, male and female Australian Wood Ducks vary in size and appearance. Males tend to have a darker head and smaller mane with speckled brown-grey bodies, a black undertail and black lower belly. Females have paler heads with white stripes above and below their eyes. Their breast and flanks are also speckled with a white undertail and white lower belly. BEHAVIOUR DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT Unlike most ducks, Australian Wood Ducks do not favour Australian Wood Ducks are found across most of Australia. swimming and will only enter open water if they’re Flocks of hundreds of birds can be found gathering disturbed. Instead, they prefer to waddle around and graze in southern areas of Australia in autumn and winter. -

Reese--Waterfowl Presentation

Waterfowl – What they are and are not Great variety in sizes, shapes, colors All have webbed feet and bills Sibley reading is great for lots of facts and insights into the group Order Anseriformes Family Anatidae – 154 species worldwide, 44 in NA Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks Subfamily Anserinae – geese & swans Subfamily Anatinae - ducks Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 (3 are rare) Swans = ?? Handout • Indicates those species occurring regularly in ID Ducks = 26 species Geese = 6 Swans = 2 What separates the 3 groups? Ducks - Geese - Swan - What separates the 3 groups? Ducks – smaller, shorter legs & necks Geese – long legs, graze in uplands Swan – shorter legs than geese, long necks, larger size, feed more often in water Non-waterfowl Cranes, rails – beak, rails have lobed feet Coots – bill but lobed feet Grebes – lobed feet Loons – webbed feet but sharp beak Woodcock and snipe – feet not webbed, beaks These are not on handout but are managed by USFWS as are waterfowl On handout: Subfamily Dendrocygninae – whistling ducks – used to be called tree ducks 2 species, more goose-like, longer necks and legs than most ducks, flight is faster than geese, but slower than other ducks Occur along gulf coast and Florida On handout: Subfamily Anserinae – geese and swans Tribe Cygnini – swans – 2 species Tribe Anserini – -

Nesting Biology. Social Patterns and Displays of the Mandarin Duck, a Ix Galericulata

pi)' NESTING BIOLOGY. SOCIAL PATTERNS AND DISPLAYS OF THE MANDARIN DUCK, A_IX GALERICULATA Richard L. Bruggers A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1974 ' __ U J 591913 W A'W .'X55’ ABSTRACT A study of pinioned, free-ranging Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) was conducted from 1971-1974 at a 25-acre estate. The purposes 'were to 1) document breeding biology and behaviors, nesting phenology, and time budgets; 2) describe displays associated with copulatory behavior, pair-formation and maintenance, and social encounters; and 3) determine the female's role in male social display and pair formation. The intensive observations (in excess of 400 h) included several full-day and all-night periods. Display patterns were recorded (partially with movies) arid analyzed. The female's role in social display was examined through a series of male and female introductions into yearling and adult male "display parties." Mandarins formed strong seasonal pair bonds, which re-formed in successive years if both individuals lived. Clutches averaged 9.5 eggs and were begun by yearling females earlier and with less fertility (78%) than adult females (90%). Incubation averaged 28-30 days. Duckling development was rapid and sexual dimorphism evident. 9 Adults and yearlings of both sexes could be separated on the basis of primary feather length; females, on secondary feather pigmentation. Mandarin daily activity patterns consisted of repetitious feeding, preening, and loafing, but the duration and patterns of each activity varied with the social periods. -

The Role of Habitat Variability and Interactions Around Nesting Cavities in Shaping Urban Bird Communities

The role of habitat variability and interactions around nesting cavities in shaping urban bird communities Andrew Munro Rogers BSc, MSc Photo: A. Rogers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Biological Sciences Andrew Rogers PhD Thesis Thesis Abstract Inter-specific interactions around resources, such as nesting sites, are an important factor by which invasive species impact native communities. As resource availability varies across different environments, competition for resources and invasive species impacts around those resources change. In urban environments, changes in habitat structure and the addition of introduced species has led to significant changes in species composition and abundance, but the extent to which such changes have altered competition over resources is not well understood. Australia’s cities are relatively recent, many of them located in coastal and biodiversity-rich areas, where conservation efforts have the opportunity to benefit many species. Australia hosts a very large diversity of cavity-nesting species, across multiple families of birds and mammals. Of particular interest are cavity-breeding species that have been significantly impacted by the loss of available nesting resources in large, old, hollow- bearing trees. Cavity-breeding species have also been impacted by the addition of cavity- breeding invasive species, increasing the competition for the remaining nesting sites. The results of this additional competition have not been quantified in most cavity breeding communities in Australia. Our understanding of the importance of inter-specific interactions in shaping the outcomes of urbanization and invasion remains very limited across Australian communities. This has led to significant gaps in the understanding of the drivers of inter- specific interactions and how such interactions shape resource use in highly modified environments. -

2.9 Waterbirds: Identification, Rehabilitation and Management

Chapter 2.9 — Freshwater birds: identification, rehabilitation and management• 193 2.9 Waterbirds: identification, rehabilitation and management Phil Straw Avifauna Research & Services Australia Abstract All waterbirds and other bird species associated with wetlands, are described including how habitats are used at ephemeral and permanent wetlands in the south east of Australia. Wetland habitat has declined substantially since European settlement. Although no waterbird species have gone extinct as a result some are now listed as endangered. Reedbeds are taken as an example of how wetlands can be managed. Chapter 2.9 — Freshwater birds: identification, rehabilitation and management• 194 Introduction such as farm dams and ponds. In contrast, the Great-crested Grebe is usually associated with large Australia has a unique suite of waterbirds, lakes and deep reservoirs. many of which are endemic to this, the driest inhabited continent on earth, or to the Australasian The legs of grebes are set far back on the body region with Australia being the main stronghold making them very efficient swimmers. They forage for the species. Despite extensive losses of almost completely underwater pursuing fish and wetlands across the continent since European aquatic arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. settlement no extinctions of waterbirds have They are strong fliers but are poor at manoeuvering been recorded from the Australian mainland as in flight and generally prefer to dive underwater a consequence. However, there have been some to escape avian predators or when disturbed by dramatic declines in many populations and several humans. Flights between wetlands, some times species are now listed as threatened including over great distances, are carried out under the cover the Australasian Bittern, Botaurus poiciloptilus of darkness when it is safe from attack by most (nationally endangered). -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Index" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Index The following index is limited to the species of Anatidae; species of other bird families are not indexed, nor are subspecies included. However, vernacular names applied to certain subspecies that sometimes are considered full species are included, as are some generic names that are not utilized in this book but which are still sometimes applied to par ticular species or species groups. Complete indexing is limited to the entries that correspond to the vernacular names utilized in this book; in these cases the primary species account is indicated in italics. Other vernacular or scientific names are indexed to the section of the principal account only. Abyssinian blue-winged goose. See atratus, Cygnus, 31 Bernier teal. See Madagascan teal blue-winged goose atricapilla, Heteronetta, 365 bewickii, Cygnus, 44 acuta, Anas, 233 aucklandica, Anas, 214 Bewick swan, 38, 43, 44-47; PI. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen. -

Dietary Breadth and Foraging Habitats of the White- Bellied Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus Leucogaster) on West Australian Islands and Coastal Sites

Dietary breadth and foraging habitats of the White- bellied Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) on West Australian islands and coastal sites. Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Environmental Science Murdoch University By Shannon Clohessy Bachelor of Science (Biological Sciences and Marine and Freshwater Management) Graduate Diploma of Science (Environmental Management) 2014 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is a synthesis of my own research and has not been submitted as part of a tertiary qualification at any other institution. ……………………………………….. Shannon Clohessy 2014 2 Abstract This study looks at dietary preference of the Haliaeetus leucogaster in the Houtman Abrolhos and on coastal and near shore islands between Shark Bay and Jurien Bay. Prey species were identified through pellet dissection, which were collected from nests and feeding butcheries, along with prey remains and reference photographs. Data extracted from this process was compared against known prey types for this species. Potential foraging distances were calculated based on congeneric species data and feeding habits and used to calculate foraging habitat in the study sites and expected prey lists to compare against observed finds. Results were compared against similar studies on Haliaeetus leucogaster based in other parts of Australia. 3 Contents Figure list .................................................................................................................................. 6 Tables list ................................................................................................................................ -

African Pygmy Goose Scientific Name: Nettapus Auritus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae

African Pygmy Goose Scientific Name: Nettapus auritus Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae The African Pygmy Goose is a perching duck from the sub-Saharan Africa area. They are the smallest of Africa’s wildfowl, and one of the smallest in the world. The average weight of a male is 285 grams (10.1 oz) and for the female 260 grams (9.2 oz). Their wingspan is between 142 millimeters (5.6 in) to 165 millimeters (6.5 in). The African pygmy goose has a short bill which extends up the forehead so they resemble geese. The males have a white face with black eye patches. The iridescent black crown extends down the back of the neck. The upper half of the fore neck is white whereas the base of the neck and breast are light chestnut colored. The sixteen tail feathers are black. The wing feathers are black with metallic green iridescence on the coverts. Range The African pygmy goose is found in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. They are known to be nomadic. Habitat They live in slow flowing or stagnant water with a cover of water lilies. This includes inland wetlands, open swamps, river pools, and estuaries. Gestation The female lays 6 to 12 eggs that are incubated for 23 to 26 days. Litter There is usually between 6 and 12 young with each mating. Behavior They live in strong pair bonds that can last over several seasons and their breeding is triggered by rains. Reproduction The African pygmy goose will nest in natural hollows or disused holes of barbets and woodpeckers in trees standing in or close to the water.