Qдцтсъiпдои from Fact to Fiction an Introduction to the Mythology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

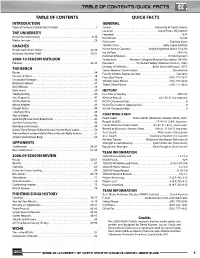

Table of Contents/Quick Facts Table Of

TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS INTRODUCTION GENERAL Table of Contents/Quick Facts/Credits . .1 School . .University of North Dakota Location . Grand Forks, ND (58202) THE UNIVERSITY Founded . 1883 University Information . .2-25 Enrollment . 12,748 Media Services . .26 Nickname . .Fighting Sioux COACHES School Colors . Kelly Green & White Head Coach Brian Idalski . 28-29 Home Arena (Capacity) . Ralph Engelstad Arena (11,634) Assistant Coaches/Sta . 30-31 Ice Surface . .200 x 85 National A liation . .NCAA Division I 2009-10 SEASON OUTLOOK Conference . Western Collegiate Hockey Association (WCHA) Preview . 32-33 President . .Dr. Robert Kelley (Abilene Christian, 1965) Director of Athletics . Brian Faison (Missouri, 1972) THE BENCH Senior Woman Administrator . Daniella Irle Roster . .34 Faculty Athletic Representative . Sue Jeno Susanne Fellner . .35 Press Box Phone . (701) 777-3571 Cassandra Flanagan . .36 Athletic Dept. Phone . (701) 777-2234 Brittany Kirkham . .37 Ticket O ce Phone . (701) 777-0855 Alex Williams . .38 Kelly Lewis . .39 HISTORY Stephanie Roy . .40 First Year of Hockey . 2002-03 Sara Dagenais. .41 All-time Record . 62-150-21 (six seasons) Ashley Holmes . .42 NCAA Championships . .0 Kelsey Ketcher . .43 NCAA Tournament Appearances . .0 Margot Miller . .44 WCHA Championships . .0 Stephanie Ney . .45 Alyssa Wiebe . .46 COACHING STAFF Jorid Dag nrud/Janet Babchishin . .47 Head Coach . Brian Idalski (Wisconsin-Stevens Point, 2001) Jocelyne Lamoureux . .48 Record at UND . .17-41-10 (.324), two years Monique Lamoureux . .49 Career Record as Head Coach . 125-62-21 (.651), seven years Ashley Furia/Megan Gilbert/Jessica Harren/Mary Loken . .50 Record at Wisconsin-Stevens Point . .108-21-11 (.811), ve years Alanna Moir/Candace Molle/Allison Parizek/Holly Perkins . -

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Oriana Palusci and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0353-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0353-3 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Alice Munro’s Short Stories in the Anatomy Theatre Oriana Palusci Section I: The Resonance of Language Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Dance of Happy Polysemy: The Reverberations of Alice Munro’s Language Héliane Ventura Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 27 Too Much Curiosity? The Late Fiction of Alice Munro Janice Kulyk Keefer Section II: Story Bricks Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 45 Alice Munro as the Master -

2020-21 WCHA Men's League WEEKLY RELEASE 2020-21 SEASON REVIEW/ Wcha.Com

TM TM 2020-21 WCHA Men's League WEEKLY RELEASE 2020-21 SEASON REVIEW/ wcha.com CONTACT: TODD BELL / O: 952-681-7668 / C: 972-825-6686 / [email protected] 2020-21 WCHA STANDINGS Conference Overall Rk (Natl Rank) Team Pts GP W L T OTW/OTL SW Pts.% GF GA GP W L T GF GA 1. (4/3) Minnesota State^ 39 14 13 1 0 1/1 0 .929 56 15 28 22 5 1 100 46 2, (14/13) Lake Superior State* 27 14 9 5 0 2/2 0 .643 39 34 28 19 7 3 86 63 (18/RV) Bowling Green* 27 14 8 5 1 0/2 0 .643 46 34 31 20 10 1 108 67 4. (10/10) Bemidji State* 24 14 8 5 1 3/2 0 .571 42 34 29 16 10 3 82 70 5. (RV/UR) Michigan Tech 20 14 7 7 0 1/0 0 .476 38 35 30 17 12 1 78 63 (RV/UR) Northern Michigan 20 14 6 7 1 2/2 1 .476 40 47 29 11 17 1 79 103 7. Alabama Huntsville 8 14 3 11 0 1/0 0 .190 18 49 22 3 18 1 31 80 8. Ferris State 3 14 0 13 1 0/1 1 .071 28 59 25 1 23 1 55 103 Standings presented by ^-MacNaughton Cup champion/cliched No. 1 seed for WCHA Postseason; *- Clinched home ice for the WCHA Quarterfi nals Alaska Anchorage and Alaska Fairbanks have opted out of the 2020-21 season (Three points for a regulation win; two points for a 3-on-3 or shootout win; one point for a 3-on-3 or shootout loss; zero points for a regulation loss) (Rankings are USCHO.com followed by USA Today/USA Hockey Magazine; !-March 22 poll) FINAL HORN • Minnesota State Advances to the Frozen Four: Minnesota State capped • Milestones: In addition to Minnesota State's unprecedented fourth another stellar season with the program's first Frozen Four appearance. -

Cumulative List of Jury Members For

CUMULATIVE LIST OF PEER ASSESSMENT COMMITTEE MEMBERS FOR THE GOVERNOR GENERAL'S LITERARY AWARDS LISTE CUMULATIVE DES MEMBRES DES COMITÉS D’ÉVALUATION PAR LES PAIRS POUR LES PRIX LITTÉRAIRES DU GOUVERNEUR GÉNÉRAL YEAR CHAIRPERSON ENGLISH SECTION FRENCH SECTION ANNÉE PRÉSIDENT SECTION ANGLAISE SECTION FRANÇAISE 1958 Donald Grant Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Guy Sylvestre (Chair/prés.) Robertson Davies Jean-Charles Bonenfant Douglas LePan Robert Élie 1959 Donald Grant Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Guy Sylvestre (Chair/prés.) Robertson Davies Jean-Charles Bonenfant Douglas LePan Roger Duhamel 1960 Guy Sylvestre Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) Alfred Bailey Jean-Charles Bonenfant Robertson Davies Clément Lockquell 1961 Guy Sylvestre Northrop Frye (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) Alfred Bailey Léopold Lamontagne Roy Daniells Clément Lockquell 1962 Northrop Frye Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Léopold Lamontagne Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1963 Northrop Frye Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Roger Duhamel (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Léopold Lamontagne Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1964 Roger Duhamel Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Bernard Julien Mary Winspear Clément Lockquell 1965 Roger Duhamel Roy Daniells (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) F.W. Watt Bernard Julien Mary Winspear Adrien Thério 1966 Roy Daniells Robert Weaver (Chair/prés.) Léopold Lamontagne (Chair/prés.) Henry Kreisel Jean Filiatrault Mary Winspear Bernard Julien 1967 -

Filgate's First Person Singular

= F I L M R E v I E w 5 • • the Candid Eye technique at the Nation hot); the young son of peace activist way read one of Callaghan's short Terence Maccartney stories, while the young writer sat op al Film Board in the '50s. Filgate dis Kate Nelligan disappears - "where's Gil posite him with the galleys of an early plays all his formidable background and ligan!" - (worries a lot of people includ Filgate's Hemingway novel. expertise in this fine example of a docu ing his mom) and is eventually found This encounter led Hemingway to get mentary that captures the flavour, merit alive (but really cold) in a secret bomb shelter morgue. Morley Callaghan some of Callaghan's short stories pub and yes, ego of a leading Canadian writ lished in American magazines in Paris, er, and a lot of details and tales of his There are many such diversionary, and to Morley and his bride arriving at early life. The weaving of the present time-killing subplots in which several First Person that fabulous city in the '20s, where day with the past, the setting of the relationships begin to take shape. But they met with Hemingway and other il period, all skilfully blend to capture and only in one instance do two characters Singular: lustrious literary leading lights -F. Scott enthrall the imagination, so that the engage in a straightforward dialogue Fitzerald, Ezra Pound, James Joyce. viewer is left wanting to know more about the greater implications of living in a bomb shelter in 1987. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Stuart Ross to Receive the 2019 Harbourfront Festival Prize

Stuart Ross to Receive the 2019 Harbourfront Festival Prize TORONTO, September 17, 2019 – The Toronto International Festival of Authors (TIFA), Canada’s largest and longest-running festival of words and ideas, today announced that this year’s Harbourfront Festival Prize will be awarded to writer and poet Stuart Ross. Established in 1984, the Harbourfront Festival Prize of $10,000 is presented annually in recognition of an author's contribution to the Canadian literature community. The award will be presented to Ross on Sunday, October 27 at 4pm as part of TIFA’s annual GGbooks: A Festival Celebration event, hosted by Carol Off. Ross will also appear at TIFA as part of Small Press, Big Ideas: A Roundtable on Saturday, October 26, 2019 at 5pm. TIFA takes place from October 24 to November 3 and tickets are on sale at FestivalOfAuthors.ca. Stuart Ross is a writer, editor, writing teacher and small press activist living in Cobourg, Ontario. He is the author of 20 books of poetry, fiction and essays, most recently the poetry collection Motel of the Opposable Thumbs and the novel in prose poems Pockets. Ross is a founding member of the Meet The Presses collective, has taught writing workshops across the country, and was the 2010 Writer In Residence at Queen’s University. He is the winner of TIFA’s 2017 PoetryNOW:Battle of the Bards competition, the 2017 Jewish Literary Award for Poetry, and the 2010 ReLit Award for Short Fiction, among others. His micro press, Proper Tales, is in its 40th year. “I am both stunned and honoured to receive this award. -

Quiz Des Canadiens De Montréal

QUIZ DES CANADIENS DE MONTRÉAL 1 En quelle année les Canadiens de Montréal ont été fondés ? 2 Combien d’équipes faisaient partie des équipes originales de la LNH entre 1942-43 et 1966-67 ? 3 Quels sont les noms des assistants capitaine de l’équipe ? 4 Comment se nomme l’équipe de l’AHL appartenant aux Canadiens ? 5 Comment se nomme la mascotte de l’équipe des Canadiens de Montréal ? 6 À quelle équipe appartenait Youppi! avant d’appartenir aux Canadiens ? 7 Comment se nomme la mascotte du Rocket de Laval ? 8 En quelle année les Canadiens de Montréal ont remporté leur première coupe Stanley ? 9 On me surnomme le Rocket. Qui suis-je ? 10 On me surnomme Boum Boum. Qui suis-je ? 11 Qui est le numéro 31 des Canadiens de Montréal ? 12 Qui est le directeur général de l’équipe ? 13 Combien d’équipes sont membres de la LNH ? 14 Qui est le numéro 24 de l’équipe des Canadiens de Montréal ? 15 Qui est le premier gardien de but à porter un masque régulièrement durant les matchs ? 1 MONTREAL CANADIENS QUIZ 1 In what year were the Canadiens founded? 2 How many teams were there in the NHL between 1942-43 and 1966-67? 3 What are the names of the Canadiens’ alternate captains? 4 What is the name of the Canadiens’ AHL affi liate? 5 What is the name of the Montreal Canadiens’ mascot? 6 To which team did Youppi! belong before joining the Canadiens? 7 What is the name of the Laval Rocket’s mascot? 8 In what year did the Montreal Canadiens win their fi rst Stanley Cup? 9 My nickname is the Rocket. -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Prize Possession: Literary Awards, the GGs, and the CanLit Nation by Owen Percy A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY 2010 ©OwenPercy 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.