Fossey, Dian. 1973. “The Mountain Gorilla” [Audio Recorded Lecture to National Geographic Society Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jane Goodall: a Timeline 3

Discussion Guide Table of Contents The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline 3 Growing Up: Jane Goodall’s Mission Starts Early 5 Louis Leakey and the ‘Trimates’ 7 Getting Started at Gombe 9 The Gombe Community 10 A Family of Her Own 12 A Lifelong Mission 14 Women in the Biological Sciences Today 17 Jane Goodall, in Her Own Words 18 Additional Resources for Further Study 19 © 2017 NGC Network US, LLC and NGC Network International, LLC. All rights reserved. 2 Journeys in Film : JANE The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline April 3, 1934 Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall is born in London, England. 1952 Jane graduates from secondary school, attends secretarial school, and gets a job at Oxford University. 1957 At the invitation of a school friend, Jane sails to Kenya, meets Dr. Louis Leakey, and takes a job as his secretary. 1960 Jane begins her observations of the chimpanzees at what was then Gombe Stream Game Reserve, taking careful notes. Her mother is her companion from July to November. 1961 The chimpanzee Jane has named David Greybeard accepts her, leading to her acceptance by the other chimpanzees. 1962 Jane goes to Cambridge University to pursue a doctorate, despite not having any undergraduate college degree. After the first term, she returns to Africa to continue her study of the chimpanzees. She continues to travel back and forth between Cambridge and Gombe for several years. Baron Hugo van Lawick, a photographer for National Geographic, begins taking photos and films at Gombe. 1964 Jane and Hugo marry in England and return to Gombe. -

Eowilson CV 25 Aprili 2018

Curriculum Vitae Edward Osborne Wilson BORN: Birmingham, Alabama, June 10, 1929; parents: Inez Linnette Freeman and Edward Osborne Wilson, Sr. (deceased). Married: Irene Kelley, 1955. One daughter: Catherine, born 1963. EDUCATION: Graduated Decatur Senior High School, Decatur, Alabama, 1946 B.S. (biol.), University of Alabama, 1949 M.S. (biol.), University of Alabama, 1950 Ph.D. (biol.), Harvard University, 1955 POSITIONS: Alabama Department of Conservation: Entomologist, 1949 National Science Board Taskforce on Biodiversity, 1987–89 Harvard University: Junior Fellow, Society of Fellows, 1953– Xerces Society: President, 1989–90 56; Assistant Professor of Biology, 1956–58; Associate The Nature Conservancy, Board of Directors, 1993–1998 Professor of Zoology, 1958–64; Professor of Zoology, 1964– American Academy for Liberal Education: Founding Director, 1976; Curator in Entomology, Museum of Comparative 1992–2004 Zoology, 1973–97; Honorary Curator in Entomology, New York Botanical Garden: Board of Directors, 1992–95; Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1997–; Frank B. Baird Jr. Honorary Manager of the Board of Directors, 1995– Professor of Science, 1976–1994; Mellon Professor of the American Museum of Natural History: Board of Directors, Sciences, 1990–1993; Pellegrino University Professor, 1994– 1993–2002; Lifetime Honorary Trustee, 2002– June 1997; Pellegrino University Professor, Emeritus, July Conservation International, Board of Directors, 1997– 1997–December 1997; Pellegrino University Research Scientific Committee of the Ministry of the -

Remembering Dian Fossey: Primatology, Celebrity, Mythography

Kunapipi Volume 34 Issue 2 Article 16 2012 Remembering Dian Fossey: Primatology, Celebrity, Mythography Graham Huggan Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Huggan, Graham, Remembering Dian Fossey: Primatology, Celebrity, Mythography, Kunapipi, 34(2), 2012. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol34/iss2/16 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Remembering Dian Fossey: Primatology, Celebrity, Mythography Abstract It is generally accepted today that the turbulent life of the American primatologist Dian Fossey developed over time into the stuff of legend; so much so that its singularly nasty end — she was murdered in 1985 in circumstances that are still far from certain — is seen by some as ‘something she might well have made up for herself’ (Torgovnick 91). Fossey’s celebrity (or, perhaps better, her notoriety) is attributable to several different factors, not least the 1988 Hollywood film (Gorillas in the Mist) celebrating her exploits. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol34/iss2/16 136 GRAHAM HUGGAN Remembering Dian Fossey: primatology, Celebrity, Mythography It is generally accepted today that the turbulent life of the American primatologist Dian Fossey developed over time into the stuff of legend; so much so that its singularly nasty end — she was murdered in 1985 in circumstances that are still far from certain — is seen by some as ‘something she might well have made up for herself’ (Torgovnick 91). -

Dian Fossey's Gorillas 50 Years On

Dian Fossey’s gorillas 50 years on: research, conservation, and lessons learned Stacy Rosenbaum Institute for Mind and Biology University of Chicago An Outline 1. A brief history (natural and human) 2. The mission today àProtect, educate, develop, learn 3. My role: ongoing research 4. Successes, lessons learned, and why it all matters Two gorilla species: western & eastern Uganda Democratic Republic of Congo Rwanda KARISOKE History of mountain gorillas in western science • 1901- Western science ‘discovers’ mountain gorillas • 1920s - Carl Akeley expeditions lead to Albert National Park • 1960 - George Schaller writes first scientific articles • 1967 – Dian Fossey establishes Karisoke Research Center • 2016 – 70+ scientists contributed to knowledge of behavior, ecology 1963: Dian Fossey meets renowned anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey She encounters mountain gorillas for the first time, and persuades Leakey to hire her Karisoke Research Center 1967-ongoing… Observing behavior • Habituated groups for study • Fossey learned to observe individuals KarisokeKarisoke Research Research Center Center 1967-ongoing…1967-ongoing… Karisoke’s central objectives • Protection • Education • Community Development • Research* Protection & conservation historically Protection & conservation today Illegal activities Habitat Loss Direct poaching Disease transmission Gorilla protection & monitoring • Protection and monitoring for habituated gorilla groups • Assistance to national park authorities Democratic Republic Uganda of Congo Rwanda Education Sites of engagement: • Primary classrooms • Zoos (USA) • Social media • National University of Rwanda “Citizen science” project Community development Combating poverty = improved conservation outcomes Hospital building Toilet facilities Water tanks Treating intestinal parasites Solar generators Gorilla Research Program Key Karisoke research findings • Gorillas aren’t King Kong! • Socioecological principles • Male and female dispersal • Population census Ongoing project #1: Mountain gorilla stress physiology Stress: causes & consequences Drs. -

About Primates!

ALL ABOUT PRIMATES! Gorilla World and Jungle Trails WHAT IS A PRIMATE? Primates are a taxonomical Order of related species that fall under the Class Mammalia Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Primates From here primates tend to fall into 3 major categories THE THREE PRIMATE CATEGORIES Prosimians Monkeys Apes PROSIMIANS Prosimians represent the more “primitive” of primates General Characteristics: Small Size Nocturnal Well-developed sense of smell Relatively Solitary Vertical Clingers and Leapers This group includes all lemurs, galagos, lorises, and tarsiers MONKEYS Monkeys are the most geographically diverse category of primates, spanning throughout South and Central America, Africa, Asia, and even one location in Europe General Characteristics Long Tails Diurnal (one exception) Increased sense of sight More complex social structures Increased Intelligence Quadrupedal Monkeys are classified as either New World or Old World NEW WORLD VS. OLD WORLD MONKEYS New World Monkeys span Old World Monkeys span throughout Central and throughout Europe, Africa, and South America. Asia. Characteristics: Round, flat Characteristics: Narrow, nostrils. Smaller in size. downward nostrils. Larger in Exclusively arboreal. Some size. Some terrestrial. Sitting have prehensile tails. pads, Some have cheek pouches. APES Apes are often known as the most “advanced” group of primates General Characteristics No Tail Large in size Broad Chests Move through brachiation High intelligence Dependence on learning and tool use This group includes -

12.4 Words Mx

words Being objective The idea of scientists as impartial observers is hard to shake, but is complete detachment justified? Mary Midgley hat does it mean to be objective? ife, consciousness John B. Watson, the founding and purpose are Wfather of behaviourism, had no L doubts about this. For him, the word meant natural facts in the world simply ‘avoiding emotion’. Thus, in giving advice about parental behaviour, he wrote: like any others, and in “There is a sensible way of treating chil- some contexts they are dren. Treat them as though they were young adults… Let your behaviour always be objec- vitally important facts. tive and kindly firm. Never hug and kiss them, never let them sit on your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say good night. Shake hands with them gist, never had to consider whether this law in the morning…” (Psychological Care of actually extended to cover everything in Infant and Child 9–10; W. W. Norton, New nature, including active organisms such as York, 1928). small children. And again — as he too was As he knew that parents were prone to part of nature — was his own purpose in make this kind of mistake, he had grave writing his books real or not? He doesn’t say. doubts about whether they should be allowed He took all purpose to be illusory and the dif- to bring up their children at all, or indeed to ference between living and lifeless matter, have anything to do with them. “There are,” sentience and unconsciousness, to be some- he noted, “undoubtedly more scientific ways how a trivial one, beneath the notice of sci- of bringing up children, which probably ence. -

Trimates” January 6Th, 2021 but First… • What Is an Ape? • What Is a Primate? • What Is a Mammal? What Makes a Mammal?

ANBI 133: Great Ape Ecology and Evolution The “Trimates” January 6th, 2021 But first… • What is an ape? • What is a primate? • What is a mammal? What makes a mammal? • Mammals • Mammary glands • Hair or fur • Three middle ear bones • Primate reproduction (and a lot of behavior) is constrained by mammalian anatomy • Female gestation and lactation • Female investment in offspring is obligatory • Male care varies What Makes a Primate? • No unique characteristic common to all primates to the exclusion of all other mammals • Suite of characteristics • Grasping hand with opposable big toe and/or thumb with nails instead of claws (on at least some digits) What Makes a Primate? • No unique characteristic common to all primates to the exclusion of all other mammals • Suite of characteristics • Decreased importance of smell/ Increased reliance on vision • Forward-facing eyes and binocular vision • Trichromatic vision in old world primates What Makes a Primate? • No unique characteristic common to all primates to the exclusion of all other mammals • Suite of characteristics • Large brains • Increased investment in offspring • Increased dependence on learning and behavioral flexibility What Makes a Primate? • No unique characteristic common to all primates to the exclusion of all other mammals • Suite of characteristics • Unspecialized dentition • Dietary flexibility • Mainly restricted to living in the tropics Primate Origins • 54-65 mya (Paleocene, North America) • Extinction of dinosaurs • Angiosperm and mammal adaptive radiation Primate Origins -

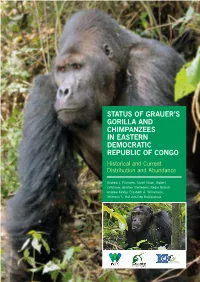

Status of Grauer's Gorilla and Chimpanzees in Eastern

Status of Grauer’s gorilla and chimpanzees in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 1 STATUS OF GRAUER’S GORILLA AND CHIMPANZEES IN EASTERN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Historical and Current Distribution and Abundance Andrew J. Plumptre, Stuart Nixon, Robert Critchlow, Ghislain Vieilledent, Radar Nishuli, Andrew Kirkby, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Jefferson S. Hall and Deo Kujirakwinja STATUS OF GRAUER’S GORILLA AND CHIMPANZEES IN EASTERN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Historical and Current Distribution and Abundance Andrew J. Plumptre1 Stuart Nixon2* Robert Critchlow3 Ghislain Vieilledent4 Radar Nishuli5 Andrew Kirkby1 Elizabeth A. Williamson6 Jefferson S. Hall7 Deo Kujirakwinja1 1. Wildlife Conservation Society, 2300 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, New York 10460, USA 2. North of England Zoological Society, Chester Zoo, Upton by Chester,CH2 1LH, UK 3. Department of Biology, University of York, York, UK 4. CIRAD, UPR BSEF, F-34398 Montpellier, France 5. Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN),Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo 6. School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK 7. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Av. Roosevelt 401, Balboa, Ancon, Panama *Formerly Fauna & Flora International, David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge, CB2 3QZ ISBN 10: 0-9792418-5-5 Front and back cover photos: A.Plumptre/WCS ISBN 13: 978-0-9792418-5-7 Status of Grauer’s gorilla and chimpanzees in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) saves wildlife and wild EXECUTIVE SUMMARY places worldwide through science, conservation action, education, and inspiring people to value nature. WCS envisions a world where wildlife thrives in healthy lands and seas, valued by societies that This report summarises the current state of knowledge on the Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... -

Eowilson CV 17 September 2020

Curriculum Vitae Edward Osborne Wilson BORN: Birmingham, Alabama, June 10, 1929; parents: Inez Linnette Freeman and Edward Osborne Wilson, Sr. (deceased). Married: Irene Kelley, 1955. One daughter: Catherine, born 1963. EDUCATION: Graduated Decatur Senior High School, Decatur, Alabama, 1946 B.S. (biol.), University of Alabama, 1949 M.S. (biol.), University of Alabama, 1950 Ph.D. (biol.), Harvard University, 1955 POSITIONS: Alabama Department of Conservation: Entomologist, 1949 Xerces Society: President, 1989–90 Harvard University: Junior Fellow, Society of Fellows, 1953– The Nature Conservancy, Board of Directors, 1993–1998 56; Assistant Professor of Biology, 1956–58; Associate American Academy for Liberal Education: Founding Director, Professor of Zoology, 1958–64; Professor of Zoology, 1964– 1992–2004 1976; Curator in Entomology, Museum of Comparative New York Botanical Garden: Board of Directors, 1992–95; Zoology, 1973–97; Honorary Curator in Entomology, Honorary Manager of the Board of Directors, 1995– Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1997–; Frank B. Baird Jr. American Museum of Natural History: Board of Directors, Professor of Science, 1976–1994; Mellon Professor of the 1993–2002; Lifetime Honorary Trustee, 2002– Sciences, 1990–1993; Pellegrino University Professor, 1994– Conservation International, Board of Directors, 1997– June 1997; Pellegrino University Professor, Emeritus, July Scientific Committee of the Ministry of the Environment, 1997–December 1997; Pellegrino University Research Colombia, 1999– Professor, December 9, 1997–2002; -

CONSERVATION and SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONSERVATION and SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020

CONSERVATION and SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONTENTS 03 A message from Dr. Kreger 04 Executive Summary 07 Saving Species: National Wildlife 13 Saving Spcies: International Wildlife 21 Wildlife Trade 22 Conservation Fundraising 23 Sustainability 25 Publications List A MESSAGE FROM DR. MICHAEL KREGER I write this in June 2021. It is a hopeful Rescue & Rehabilitation Partnership. time as people are getting vaccinated, We provided emergency support to businesses are reopening, and Zoos Victoria for rescuing animals guests are enthusiastically returning affected by the bushfires in Australia. to the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium We continued reintroduction projects along with The Wilds, Zoombezi Bay, for the American burying beetle and Safari Golf Club. Last year at this and Eastern hellbenders. Due to time, we did not know what the future our over 30-year old partnerships in held. On the most beautiful sunny Central and Eastern Africa, Partners In days, our parking lots were empty. Conservation (PIC) was able to work People in Ohio and worldwide were virtually with cooperatives and gorilla suffering from the pandemic, many conservation organizations without not surviving. an in-person annual visit. In fact, both of the conservation fundraisers, the And what about wildlife conservation? Rwandan Fête and Wine For Wildlife, Over the years, we supported tested out a virtual format. We would projects that help people living with have rather held in-person events, but wildlife to monitor those animals, our supporters still tuned in and gave MICHAEL KREGER, PH.D. fight poaching, educate and build generously so we could continue our Vice President of awareness, encourage human-wildlife conservation efforts. -

Dr Birute Galdikas

PATRON - Orangutan Foundation International Australia DR.BIRUTE MARY GALDIKAS - Founder and President of Orangutan Foundation International BSc. Psychology & Zoology; MSc. Anthropology Scientist, conservationist, educator: for almost four decades Dr. Biruté Mary Galdikas has studied and worked closely with the orangutans of Indonesian Borneo in their natural habitat, and is today the world’s foremost authority on the orangutan. Galdikas was born after the end of World War II, while her parents were en route to Canada from their homeland of Lithuania. Galdikas grew up and went to school in Toronto. After checking out her first library book, Curious George, at the age of six, Galdikas was inspired by the man in the yellow hat and his unruly monkey. By the second grade, she had decided on her life’s work: she wanted to be an explorer. When her family moved from Canada to the United States in 1964, Galdikas had completed a year of studies at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver. She continued her studies of natural sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), quickly earning her bachelor’s degree in psychology and zoology in 1966 and her master’s degree in anthropology in 1969. It was there as a graduate student that she first met Kenyan anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey and spoke with him about her desire to study orangutans. Although Dr. Leakey seemed disinterested at first, Galdikas persuaded him of her passion. After three years, Dr. Leakey finally found the funding for Galdikas’ orangutan studies, as he had previously done with both Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey for their respective studies on chimpanzees and mountain gorillas. -

Reflections of Eden-My Years with Tans in Their Jungle Habitat

Book Reviews Karen Oates Department Editor mysterious fevers; this investigator in- states, "For me, studying and rescuing PRIMATOLOGY trepidly seeks out the elusive orangu- orangutans wasn't a project or a job, Reflections of Eden-My Years with tans in their jungle habitat. In fact, the but a mission!" Her story relates the the Orangutans of Borneo. By Birute name orangutan comes from two Ma- years studying the orangutans, her ef- M. F. Galdikas. 1995. Little, Brown and lay words meaning 'person of the for- forts to rescue and rehabilitate captive Company (NY). 408 pp. Hardback $24.95. est'. With patience, one sees that the animals, and how the fieldwork shaped her life. "The living conditions, Birute Galdikas writes about orangutans slowly reveal themselves, and can be identified and tracked so the funding difficulties, the practical F her years spent studying the that part of their life histories are re- problems, the highs of discovery, the last arboreal great ape in the Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/58/6/381/47684/4450183.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 corded false starts and the dead ends, the tropical jungles of Borneo. One of the over the years. drudgery of scientific record-keeping, three 'trimates' sponsored by the char- Orangutans lead mostly a solitary the learning how to get along with ismatic Louis Leakey to study pri- life style which is an adaptation to the people and societies initially very for- mates, this determined anthropologist environment. Because food sources are widely in eign to you, the learning how to get felt compelled to study one of the great scattered the jungle, and be- along without people, places, and apes to continue the search for insights cause the great apes require much sus- things you once took for granted, the that their behavior might yield about tenance, the land cannot support their feeling of suspension in time as the human nature and human origins.