Middle East Brief, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement A UPA Collection from Cover: Map of the Middle East. Illustration courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook. National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Guide by Dan Elasky A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road ● Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. –– (National security files) “Microfilmed from the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Dan Elasky, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. ISBN 1-55655-925-9 1. Middle East––Politics and government––1945–1979––Sources. 2. United States–– Foreign relations––Middle East. 3. Middle East––Foreign relations––United States. 4. John F. Kennedy Library––Archives. I. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. II. Series. DS63.1 956.04––dc22 2007061516 Copyright © 2007 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

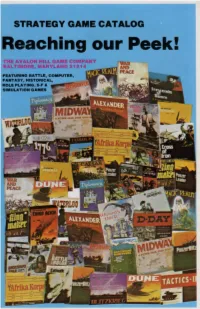

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

Hatay Devleti Millet Meclisi Üzerinde Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi Ve Tbmm'nin

Marmara Üniversitesi Öneri Dergisi • Cilt 13, Sayı 50, Temmuz 2018, ISSN 1300-0845, ss. 247-265 DO1: 10.14783/maruoneri.v13i38778.352383 HATAY DEVLEti MilleT Meclisi ÜzerinDE CUMHuriyeT * HALK PARtisi VE TBMM’nin Etkileri 1 THE IMPACTS OF REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY AND TURKISH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ON NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF HATAY STATE ** Meral BALCI 2 Öz Mondros Mütarekesi’nin sonrasında Fransız işgaline uğrayan İskenderun Sancağı (Hatay) bölgesi 1921 yılında Türkiye ile Fransa arasında yapılan anlaşma ile Suriye’ye bağlı, mandater, özerk bir bölge olarak tanımlanmıştır. Bu tarihten sonra hem Ankara Hükümeti hem de Abdurrahman Melek, Tayfur Sökmen, Abdulgani Türkmen gibi Hatay bölgesinin önde gelen isimleri Hatay’ın Türkiye topraklarına katılabilmesi için yoğun çaba sarf etmişlerdir. 1937 yılında Milletler Cemiyeti Sancak’a özel bir statü tanımış ve Sancak Anayasası oluşturulmuştur. Bunun yanı sıra Sancak’ın geleceği hakkında karar ve- recek bir meclis oluşturabilmek adına seçim yapılması öngörülmüştür. İlk olarak, Hatay Halk Partisi kurulmuş, Hatay Millet Meclisi için seçim yapılmış ve seçilen 40 milletvekilinin 22’si Türklerden oluş- muştur. Ayrıca, Ankara Hükümeti ile doğrudan temas halinde olan Hatay’ın ileri gelen Türkleri Ha- tay Devleti’nin en üst makamlarında bulunmuşlardır. Hatay Hükümeti’nin Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi programına benzer bir program oluşturması ve Hatay Millet Meclisi’nin 1924 Anayasası’na benzer ya- salar çıkarmaları gibi gelişmeler Hatay Millet Meclisi’nin Türkiye’ye katılma kararı alacağının haber- cisi olmuştur. Anahtar Kelimeler: CHP, TBMM, Anayasa, Hatay, Türkiye JEL Sınıflaması: Z18, Z38, Z28 * Makale Gönderim Tarihi: 14.11.2017; Kabul Tarihi: 22.02.2018 ** Marmara Üniversitesi, Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi,Siyaset Bilimi ve Kamu Yönetimi Bilimi, Dr. -

TODD LOCKWOOD the Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV the LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC

ThE ™ SAgA IVBooK COVER ART TODD LOCKWOOD The Neverwinter™ Saga, Book IV THE LAST THRESHOLD ©2013 Wizards of the Coast LLC. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unau- thorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast LLC. Published by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Manufactured by: Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 2 Roundwood Ave, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1AZ, UK. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, WIZARDS OF THE COAST, NEVERWINTER, FORGOTTEN REALMS, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coin- cidental. All Wizards of the Coast characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast LLC. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. Cover art by Todd Lockwood First Printing: March 2013 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN: 978-0-7869-6364-5 620A2245000001 EN Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress For customer service, contact: U.S., Canada, Asia Pacific, & Latin America: Wizards of the Coast LLC, P.O. Box 707, Renton, WA 98057- 0707, +1-800-324-6496, www.wizards.com/customerservice U.K., Eire, & South Africa: Wizards of the Coast LLC, c/o Hasbro UK Ltd., P.O. Box 43, Newport, NP19 4YD, UK, Tel: +08457 12 55 99, Email: [email protected] All other countries: Wizards of the Coast p/a Hasbro Belgium NV/SA, Industrialaan 1, 1702 Groot- Bijgaarden, Belgium, Tel: +32.70.233.277, Email: [email protected] Visit our web site at www.dungeonsanddragons.com Prologue The Year of the Reborn Hero (1463 DR) ou cannot presume that this creature is natural, in any sense of Ythe word,” the dark-skinned Shadovar woman known as the Shifter told the old graybeard. -

The AVALON HILL

$2.50 The AVALON HILL July-August 1981 Volume 18, Number 2 3 A,--LJ;l.,,,, GE!Jco L!J~ &~~ 2~~ BRIDGE 8-1-2 4-2-3 4-4 4-6 10-4 5-4 This revision of a classic game you've long awaited is the culmination What's Inside . .. of five years of intensive research and playtest. The resuit. we 22" x 28" Fuli-color Mapboard of Ardennes Battlefield believe, will provide you pleasure for many years to come. Countersheet with 260 American, British and German Units For you historical buffs, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is the last word in countersheet of 117 Utility Markers accuracy. Official American and German documents, maps and Time Record Card actual battle reports (many very difficult to obtain) were consuited WI German Order of Appearance Card to ensure that both the order of battle and mapboard are correct Allied Order of Appearance Card to the last detail. Every fact was checked and double-checked. Rules Manual The reSUlt-you move the actual units over the same terrain that One Die their historical counterparts did in 1944. For the rest of you who are looking for a good, playable game, BATTLE OF THE BULGE is an operational recreation of the famous don't look any further. "BULGE" was designed to be FUN! This Ardennes battle of December, 1944-January, 1945. means a simple, streamlined playing system that gives you time to Each unit represents one of the regiments that actually make decisions instead of shuffling paper. The rules are short and participated (or might have participated) in the battle. -

Reconsidering the Annexation of the Sanjak of the Alexandretta Through Local Narratives

RECONSIDERING THE ANNEXATION OF THE SANJAK OF THE ALEXANDRETTA THROUGH LOCAL NARRATIVES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY SITKIYE MATKAP IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES DECEMBER 2009 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Raşit Kaya Head of Department That is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science Assist. Prof. Dr. Nesim Şeker Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Nesim Şeker (METU, HIST) Assist. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, ADM) Assist. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Şen (METU, SOC) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: SITKIYE MATKAP Signature : iii ABSTRACT RECONSIDERING THE ANNEXATION OF THE SANJAK OF THE ALEXANDRETTA THROUGH LOCAL NARRATIVES Matkap, Sıtkıye M.Sc., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Nesim Şeker December 2009, 154 pages The main aim of this thesis is to examine the history of Sanjak of Alexandretta in the Turkish nationalist historiography. -

Constructivism; Instrumentalism; Syria

Sectarianism or Geopolitics? Framing the 2011 Syrian Conflict by Tasmia Nower B.A & B.Sc., Quest University Canada, 2015 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School for International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Tasmia Nower SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Tasmia Nower Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sectarianism or Geopolitics? Framing the 2011 Syrian Conflict Examining Committee: Chair: Gerardo Otero Professor Tamir Moustafa Senior Supervisor Professor Nicole Jackson Supervisor Associate Professor Shayna Plaut External Examiner Adjunct Professor School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: August 1, 2017 ii Abstract The Syrian conflict began as an uprising against the Assad regime for political and economic reform. However, as violence escalated between the regime and opposition, the conflict drew in Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, which backed both the regime and opposition with resources. The current conflict is described as sectarian because of the increasingly antagonistic relations between the Shiite/Alawite regime and the Sunni- dominated opposition. This thesis examines how sectarian identity is politicized by investigating the role of key states during the 2011 Syrian conflict. I argue that the Syrian conflict is not essentially sectarian in nature, but rather a multi-layered conflict driven by national and regional actors through the selective deployment of violence and rhetoric. Using frame analysis, I examine Iranian, Turkish, and Saudi Arabian state media coverage of the Syrian conflict to reveal the respective states’ political position and interest in Syria. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Middle East in Crisis : a Historical and Documentary Review

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Press Libraries 1959 Middle East in Crisis : a historical and documentary review Carol A. Fisher Syracuse University Fred Krinsky Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/supress Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Carol A. and Krinsky, Fred, "Middle East in Crisis : a historical and documentary review" (1959). Syracuse University Press. 4. https://surface.syr.edu/supress/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Press by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CopiffH DATE DUE A HISTORICAL AND DOCUMENTARY REVIEW Rfl nn 1 A HISTORICAL AND DOCUMENTARY REVIEW Carol A, Fisher and Fred Krinsky su SY8. A, C u S t PIUSS The Library of Congress catalog entry for this book appears at the end of the text. 1959 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS | MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY BOOK CRAFTSMEN INC NEW ASSOCIATES, , YORK Preface This book had its inception in a common teaching experience. Although it is now almost two years since we were first involved in the preparation of materials on the Middle East for a course in the problems of American democracy, world events continue to remind us of the critical importance of the Mediterranean area. Our students were aware of an increasing variety of proposals for the role the United States should play in easing the tensions in the Middle East, but they were relatively unfamiliar with the general history and geography of the area. -

Arab World. Political and Diplomatic History 1900-1967: a Chronological

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 073 960 SO 005 278 AUTHCP Mansoor, Menahem TITLE Arab World. Political and DiplomaticHistory 1900-1967: A Chronological Study.A Descriptive Brochure. INSTITUTION National Cash Register Co., Washington,D. C. Microcard Editions SPONS AGENCY Institute of International Studies (DREW/OE), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 72 . CONTRACT OEC-0-8-000131-3544(014) NOTE 40p. AVAILABLE FROMNCR/Microcard EditiOns, 901 26th Street,N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037 (free) ERRS PRICE MF-$0.65 BC Not Available fromEDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Area Studies; *Diplomatic History; History;*Middle Eastern History; *Middle Eastern Studies;*Non Western Civilization; ProgramDescriptions IDENTIFIERS *Arab States ABSTRACT The brochure contains descriptiveintroductory material on the first of seven volumescovering the Arab world. Five volumes are devoted to a chronology ofevents throughout the Arab world (including Arab-Israel relations)from 1900 up to 1967. The last two volumes contain a keyword Indexto the events. The project contributes to the Middle Eastern Studiesand also serves as a model project to scholars and studentsconcerned with research of other world areas. The first half of thebrochure, arranged in five parts, includes: 1) a description of the projert background,problem, purpose, scope, organization, research and progress information; 2) informationon use of the computer to promotenew techniques for handling, restoring,and disseminating data concerning the Arab world; 3) useful dataon the Arab world; 4) abbreviations used in indices; and 5)acknowledgements. Over half of thepamphlet furnishes sample chronology and indexpages. (SJM) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY political,andplortiOtiO: Wory 19001967: a-,chrOribitigioal study Political and Diplomatic. History of the Arab World, 190P-07: A Chronological Stddy, published in seven volumes, is the first part of a three part project covering the Arab world, 1900-67. -

United Arab Republic 1 United Arab Republic

United Arab Republic 1 United Arab Republic ةدحتملا ةيبرعلا ةيروهمجلا Al-Gumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah Al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-MuttahidahUnited Arab Republic ← → 1958–1961 ← (1971) → ← → Flag Coat of arms Anthem Oh My Weapon[1] Capital Cairo Language(s) Arabic [2] Religion Secular (1958–1962) Islam (1962–1971) Government Confederation President - 1958–1970 Gamal Abdel Nasser United Arab Republic 2 Historical era Cold War - Established February 22, 1958 - Secession of Syria September 28, 1961 - Renamed to Egypt 1971 Area - 1961 1166049 km2 (450214 sq mi) Population - 1961 est. 32203000 Density 27.6 /km2 (71.5 /sq mi) Currency United Arab Republic pound Calling code +20 Al-Gumhuriyah al-Arabiyahةدحتملا ةيبرعلا ةيروهمجلا :The United Arab Republic (Arabic al-Muttahidah/Al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah), often abbreviated as the U.A.R., was a sovereign union between Egypt and Syria. The union began in 1958 and existed until 1961, when Syria seceded from the union. Egypt continued to be known officially as the "United Arab Republic" until 1971. The President was Gamal Abdel Nasser. During most of its existence (1958–1961) it was a member of the United Arab States, a confederation with North Yemen. The UAR adopted a flag based on the Arab Liberation Flag of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, but with two stars to represent the two parts. This continues to be the flag of Syria. In 1963, Iraq adopted a flag that was similar but with three stars, representing the hope that Iraq would join the UAR. The current flags of Egypt, Sudan, and Yemen are also based on Arab Liberation Flag of horizontal red, white, and black bands.