Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Between the Wars

JAPAN BETWEEN THE WARS The Meiji era was not followed by as neat and logical a periodi- zation. The Emperor Meiji (his era name was conflated with his person posthumously) symbolized the changes of his period so perfectly that at his death in July 1912 there was a clear sense that an era had come to an end. His successor, who was assigned the era name Taisho¯ (Great Righteousness), was never well, and demonstrated such embarrassing indications of mental illness that his son Hirohito succeeded him as regent in 1922 and re- mained in that office until his father’s death in 1926, when the era name was changed to Sho¯wa. The 1920s are often referred to as the “Taisho¯ period,” but the Taisho¯ emperor was in nominal charge only until 1922; he was unimportant in life and his death was irrelevant. Far better, then, to consider the quarter century between the Russo-Japanese War and the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident of 1931 as the next era of modern Japanese history. There is overlap at both ends, with Meiji and with the resur- gence of the military, but the years in question mark important developments in every aspect of Japanese life. They are also years of irony and paradox. Japan achieved success in joining the Great Powers and reached imperial status just as the territo- rial grabs that distinguished nineteenth-century imperialism came to an end, and its image changed with dramatic swiftness from that of newly founded empire to stubborn advocate of imperial privilege. Its military and naval might approached world standards just as those standards were about to change, and not long before the disaster of World War I produced revul- sion from armament and substituted enthusiasm for arms limi- tations. -

Afterword: Japanese Modernism Today

Afterword: Japanese Modernism Today Almost a century and a half after the Meiji Revolution (which was disguised as an imperial ‘restoration’) the concepts of ‘modernity’ and ‘modernism’ have worn rather thin. One might even say that they now seem a little old hat. The world continues to change – even more profoundly or frenetically than before – but we have become so used to constant change as a basic condition of ‘modern life’, in everything from fashion and technology to current jargon and social mores, that it hardly seems worth remarking upon. In other words, we are now so far removed from ‘tradition’ that we feel little need for contrary terms such as ‘moder- nity’ and ‘modernism’. The terms ‘postmodernity’ and ‘postmodernism’, although useful to some extent, per- haps represent, in the final analysis, only a feeble attempt to revive the moribund freshness or sense of novelty and excitement once possessed by the word ‘modern’ and its various derivatives. Without ‘tradition, ‘moder- nity’ has little meaning or function. In the Japanese case in particular, another major dif- ference between ‘now’ and ‘then’ is that, today, Japan is no longer a net ‘importer of modernity’ but is itself 276 Afterword: Japanese Modernism Today 277 a major agent of global change. In the past few decades there has been a momentous shift in the cultural ‘bal- ance of power’ between East and West, with Japan, and increasingly its larger East Asian cousin China, a major contributor to the new global economy and culture of the 21st century. Although it still continues to absorb foreign cultural influences, like every other country, Japan itself now represents ‘cutting-edge modernity’ to the rest of the world, and especially to its Asian neighbours. -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Good Development and Management of Infrastructure

Message from the Director-General Good Development and Management of Infrastructure KAZUSA Shuhei Director General, National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management (Key words) national land, civilized country, infrastructure, disaster prevention, strategic maintenance and control 1. Introduction conditions of the mountain area which They say “All roads lead to Rome,” the Roman occupies 70% of the land is subdivided Empire had a good road network and sanitary varyingly because of the strong crustal accommodations seen in the existing aqueduct. In changes and is prone to sediment disaster. Changan, an ancient Chinese capital during the The alluvial plain on which most big cities Tang Dynasty, elaborately designed city facilities exist has soft ground. based on city planning supported the prosperity ③ Earthquake-prone: This is connected to the of the city. geological conditions and ground, twenty It is still fresh in our mind that American percent of the big earthquakes with President Obama told “we determined that a magnitude 6 or more in the whole world are modern economy requires railroads and highways said to occur in Japan. Therefore, the to speed travel and commerce”1) in his inaugural earthquakes are felt strongly in the cities in speech on January 21. Without listing these which population and assets are concentrated. examples, history has shown that civilizations Also big tsunami could strike at the coast. which has constructed and maintained the good ④ Meteorological phenomena: Annual amount infrastructure prosper. of rainfall range 1,400mm to 1,600mm, which is twice of the world average. In typhoon and 2. National land and Infrastructure rainy seasons, Japan is often hit by heavy Compared to Europe and America, Japan is rain. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

Memoirs Faculty of Engineering

ISSN 0078-6659 MEMOIRS OF THE FACULTY OF ENG THE FACULTY MEMOIRS OF MEMOIRS OF THE FACULTY OF ENGINEERING OSAKA CITY UNIVERSITY INEERING OSAKA CITY UNIVERSITY VOL. 60 DECEMBER 2019 VOL. 60. 2019 PUBLISHED BY THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING OSAKA CITY UNIVERSITY 1911-0402大阪市立大学 工学部 工学部英文紀要VOL.60(2019) 1-4 見本 スミ 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 㻌 This series of Memoirs is issued annually. Selected original works of the members 㻌 of the Faculty of Engineering are compiled in the first part of the volume. Abstracts of 㻌 㻌 papers presented elsewhere during the current year are compiled in the second part. List 㻌 of conference presentations delivered during the same period is appended in the last part. 㻌 All communications with respect to Memoirs should be addressed to: 㻌 Dean of the Graduate School of Engineering 㻌 Osaka City University 㻌 3-3-138, Sugimoto, Sumiyoshi-ku 㻌 Osaka 558-8585, Japan 㻌 㻌 Editors 㻌 㻌 㻌 Akira TERAI Hayato NAKATANI This is the final print issue of “Memoirs of the Faculty of Engineering, Osaka City Masafumi MURAJI University.” This series of Memoirs has been published for the last decade in print edition as Daisuke MIYAZAKI well as in electronic edition. From the next issue, the Memoirs will be published only Hideki AZUMA electronically. The forthcoming issues will be available at the internet address: Tetsu TOKUONO https://www.eng.osaka-cu.ac.jp/en/about/publication.html. The past and present editors take Toru ENDO this opportunity to express gratitude to the subscribers for all their support and hope them to keep interested in the Memoirs. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture

PLEA2006 - The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 6-8 September 2006 Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture Cabeza-Lainez J. M, 1Saiki T. 2, Almodovar-Melendo J. M. 1, Jiménez-Verdejo J.R.2 1 Research Group KARMA, University of Seville, Spain 2 Theory of Design Division, University of Kobe, Japan ABSTRACT: Japanese Architecture has always shown an intimate connection with nature. Most materials are as natural as possible, like kaya vegetal roofing, wooden trusses and rice-straw mats (tatami). Disposition around the place, follows a clever strategy of natural balance often related to geomancy like Feng-Shui and to the observance of deeply rooted environmental rules. In this paper we would like to outline all of the former, but also stressing the role of day-lighting in architecture. Unlike Spain, day-lighting is a scarce good in Japan as the weather is often stormy and cloudy. Maximum benefit has to be taken of the periods in which the climate is pleasant, and a variety of approaches has been developed to deal with such conditions; latticed paper-windows (shôji), overhangs (noki) and verandas oriented to the South (engawa), are some of the main features that we have modelled with the aid of our computer program. The results have been validated by virtue of on site measurements. The cultural aspect of this paper lies not only in what it represents for the evolution of Japanese and Oriental Architecture but also in the profound impression that those particular lighting systems had for distinguished modern architects like Bruno Taut, Antonin Raymond or Walther Gropius and the contemporary artist Isamu Noguchi, a kind of fascination that we may say is lingering today. -

Study Guide for DE Madameby Yukio Mishima SADE Translated from the Japanese by Donald Keene

Study Guide for DE MADAMEBy Yukio Mishima SADE Translated from the Japanese by Donald Keene Written by Sophie Watkiss Edited by Rosie Dalling Rehearsal photography by Marc Brenner Production photography by Johan Persson Supported by The Bay Foundation, Noel Coward Foundation, 1 John Lyon’s Charity and Universal Consolidated Group Contents Section 1: Cast and Creative Team Section 2: An introduction to Yukio Mishima and Japanese theatre The work and life of Yukio Mishima Mishima and Shingeki theatre A chronology of Yukio Mishima’s key stage plays Section 3: MADAME DE SADE – history inspiring art The influence for Mishima’s play The historical figures of Madame de Sade and Madame de Montreuil. Renée’s marriage to the Marquis de Sade Renee’s life as Madame de Sade Easter day, 1768 The path to the destruction of the aristocracy and the French Revolution La Coste Women, power and sexuality in 18th Century France Section 4: MADAME DE SADE in production De Sade through women’s eyes The historical context of the play in performance Renée’s ‘volte-face’ The presence of the Marquis de Sade The duality of human nature Elements of design An interview with Fiona Button (Anne) Section 5: Primary sources, bibliography and endnotes 2 section 1 Cast and Creative Team Cast Frances Barber: Comtesse de Saint-Fond For the Donmar: Insignificance. Theatre includes: King Lear & The Seagull (RSC), Anthony and Cleopatra (Shakespeare’s Globe), Aladdin (Old Vic), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Edinburgh Festival & Gielgud). Film includes: Goal, Photographing Fairies, Prick Up Your Ears. Television includes: Hotel Babylon, Beautiful People, Hustle, The I.T. -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

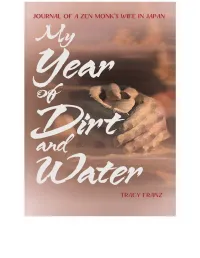

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission.