Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

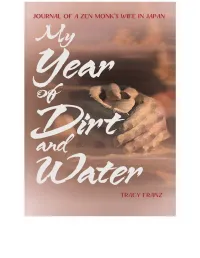

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Comparison of the “Oki-Gotatsu” in the Traditional Japanese House and the “Kürsü” in the Traditional Harput House

Intercultural Understanding, 2019, volume 9, pages 15-19 Comparison of the “Oki-gotatsu” in the Traditional Japanese House and the “Kürsü” in the Traditional Harput House ølknur Yüksel Schwamborn1 1 Architect, østanbul, Turkey Corresponding author: ølknur Yüksel Schwamborn, Architect, østanbul, Turkey, E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Japan, kotatsu, oki-gotatsu, Turkey, Anatolia, Harput, kürsü, table, heater Abstract: The use of the wooden low table “kotatsu” in the center of the traditional Japanese house in the seventeenth century (Edo (Tokugava) period), the oki-gotatsu, is similar to the use of the wooden low table in the traditional Harput house, the “kürsü”. The “kotatsu” and the “kürsü” used in winter in both places with similar climate characteristics are the table usage, which is collected around the place and where the warm-up needs are met. The origins of these similar uses in the traditional Japanese house and the traditional Harput house, located in different and distant geographies, can be traced back to Central Asia. In this study, the shape and use characteristics of “oki-gotatsu”, a form of traditional Japanese house in the past, and the shape and use characteristics of the “kürsü” in the traditional Harput house are compared. 1. Introduction area is exposed to northern and southern air currents and dominated by a cold climate, which makes life conditions In this study the traditional Japanese house wooden low table difficult. (Kahraman, 2010) Continental, polar-like air masses "kotatsu" is compared with the traditional Harput house "kürsü" originating from the inner parts of Asia move southwest before known from Turkey. -

Traditional Japanese Homes—Past and Present

NCTA ‐ Columbus Spring 2011 Sharon Drummond Traditional Japanese Homes—Past and Present Objective: Students will learn about traditional Japanese homes as described in Japanese literature and as seen in the present through print and online resources. We will use Murasaki Shikibu’s The Diary of Lady Murasaki to look at detailed descriptions of living quarters during the Heian period, read and discuss the Old Japan chapters on homes, and then compare those homes with ones shown on the Kids Web Japan website and in the book, Japan Style. Students will also learn about Japanese traditions and rituals associated with the home and its furnishings. Standards addressed: People in Societies Standard‐‐Cultures 5‐7 Benchmark A: Compare cultural practices, products, and perspectives of past civilizations in order to understand commonality and diversity of cultures. Indicator 6.1 Compare the cultural practices and products of the societies studied, including a. class structure, b. gender roles, c. beliefs, d. customs and traditions. Geography Standard—Human Environment Interaction 6‐8 Benchmark C: Explain how the environment influences the way people live in different places and the consequences of modifying the environment. Indicator 6.5 Describe ways human settlements and activities are influenced by environmental factors and processes in different places and regions including a. bodies of water; b. landforms; c. climates; d. vegetation; e. weathering; f. seismic activity. Lesson requirements: Time: one to two days; three with an extension and/or project. Materials: The Diary of Lady Murasaki, Old Japan‐Make it Work!, computer access. Optional craft materials for the extension project Lesson Plan: 1) Introduction: Read excerpts from The Diary of Lady Murasaki and ask students to list items found in the home that is described. -

Japan Unmasked

SMALL GROUP TOURS Japan Unmasked ESSENTIAL 13 Nights Tokyo > Nagano > Matsumoto > Takayama > Kanazawa > Hiroshima > Kurashiki > Kyoto > Tokyo Ride the famous shinkansen Tour Overview bullet train The tour begins in Tokyo: the beating, neon heart of Japan. The first of many rides on the Stay in a Buddhist temple shinkansen bullet train then whisks you into lodging at Nagano’s Zenko-ji mountainous Nagano, where you’ll spend Temple the night at a shukubo temple lodging, try vegetarian Buddhist cuisine and search for Observe the famous snow the key to paradise in the pitch-dark tunnels monkeys up close in Yudanaka underneath Zenko-ji - one of Japan’s most important temples. A chance for you to see the mischievous Explore the traditional craft town snow monkeys soaking in the natural hot of Takayama in the Japanese Alps spring pools of Yudanaka will be followed by a visit to the “Black Crow Castle”, Matsumoto’s Nagano magnificent original samurai fortress. After Visit the traditional samurai crossing the Northern Japanese Alps, you’ll Kanazawa and geisha districts of Kanazawa experience warm Japanese hospitality at a Tokyo Takayama Mount traditional ryokan inn in Takayama, where the Fuji old-town streets hide sake breweries, craft Matsumoto Explore the old canal district shops and morning markets loaded with of Kurashiki fresh produce. Kyoto Kyoto and Kanazawa offer a glimpse of Kurashiki traditional Japan - one a magnificent former capital with an astounding 17 World Heritage Hiroshima IJT ESSENTIAL TOURS Sites, the other a small but beautifully preserved city with lamp-lit streets and one of Flexible, fast-paced tours. -

Jlgc Newsletter

-/*&1(:6/(77(5 -DSDQ/RFDO*RYHUQPHQW&HQWHU &/$,51HZ<RUN - ,VVXHQR2FWREHU 1. Introduction of New JLGC Staff Kotaro Kashiwai, Assistant Director, Repre- sentative of Matsue City, Shimane Prefecture +HOORP\QDPHLV.RWDUR.DVKLZDL,·PIURP 0DWVXH&LW\6KLPDQH3UHIHFWXUH,·YHEHHQ JETAA USA NATIONAL CONFERENCE working for Japan Local Government Center ISSUE NO. 90 / OCTOBER 2017 VLQFHWKLV$SULO+HUH,·GOLNHWRLQWURGXFH Matsue City, which is not a well-known city, even among Japanese people. Matsue City is the capital of Shimane Prefecture, in Southwest Japan. 1. Introduction of New JLGC Staff (Page 1-5) A former feuDal strongholD, Matsue City, NQRZQDVWKH´&LW\RI:DWHUµLVDWUXHFDVWOHWRZQFURVVHG with many canals and boasts one of the twelve remaining 2. Japanese Governors original castles in Japan. Matsue City also priDes itself on AttenDed the NGA Summer Meeting (Page 6) being famous for its beautiful sunsets over Lake Shinji. As an International City of Culture and 3. USJETAA Celebrates Tourism, Matsue City and its surround- 30 Years of JET at the ing areas are rich in cultural assets and JET30 Reunion (Page 6-9) historical sites, and many of Japan's most ancient legends are set in the area. -$3$1/2&$/*29(510(17&(17(5 ϯWĂƌŬǀĞŶƵĞ͕ϮϬƚŚ&ůŽŽƌ EĞǁzŽƌŬ͕EzϭϬϬϭϲ-ϱϵϬϮ ϮϭϮ͘Ϯϰϲ͘ϱϱϰϮŽĸĐĞͻϮϭϮ͘Ϯϰϲ͘ϱϲϭϳĨĂdž ǁǁǁ͘ũůŐĐ͘ŽƌŐ ϭ 2&72%(5 ,668( 【Sightseeing】 Matsue Castle and SurrounDings Completed in 1611, Matsue Castle was built over a five-year period by Horio Yoshiharu, feudal lorD and founDer of Matsue. It was designated as a national treasure in 2015. 7KHHOHJDQFHRIWKHFDVWOH·VVZRRSLQJURRIVDQGWKHLURUQDPHQWDWLRQLV often compared to the wings of a plover birD, which has led to the FDVWOH·VQLFNQDPH3ORYHU&DVWOH7KHUHLVDPXVHXPLQVLGHDQGWKHWRSIORRURIIHUVD panoramic view of the castle grounds and the city. -

Thesis Proposal

Machiya and Transition A Study of Developmental Vernacular Architecture John E. Linam Jr. Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture Bill Galloway, Chair Dr. D. Kilper Dr. J. Wang November 30, 1999 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Machiya, Japan, Vernacular, Architecture Thesis Proposal John Linam, Jr. 411.57.8532 CAUS + VPI MACHIYA AND TRANSITION A Study of Developmental Vernacular Architecture ABSTRACT The historical, vernacular, residential forms and processes of urban Japan are to be explored as a potential source of power with regards to the concept of developmental vernacular architecture. This theory is a relatively new and vaguely defined approach to a combined method of conservation and progressive growth; balanced elements of a “smart growth” strategy. Therefore, a clarification of the term, along with an initial analysis of the definitions and values of vernacular architectures, is needed. Secondly, The Japanese machiya type will be explored as a unique vernacular form, indicating its diversity over time and similarity over distance. The essential controls and stimulus of its formal evolution and common characteristics will be examined. Machiya, a Japanese term, translates roughly to townhouse, in English. It is typically a city dwelling which also includes a small shop or metting space that fronts the street. This is the typical dwelling of the urban merchant class. The long of history of its development and its many transformations will be discussed. These analyses ultimately lead to the design exercise which investigates the machiya type as an intelligent base for a developmental vernacular process within the context of the Japanese urban environment. -

Israel Goldman Japanese Prints, Paintings and Books Recent Acquisitions 26 Catalogue 2020

Israel Goldman Israel Israel Goldman Japanese Prints, Paintings and Books Recent Acquisitions Catalogue 26 2020 Japanese Prints, and Paintings Books 26 Cat.26 Final.qxp_2020 31/08/2020 19:54 Page 1 Israel Goldman Japanese Prints, Paintings and Books Recent Acquisitions Catalogue 26 2020 Cat.26 Final.qxp_2020 31/08/2020 19:54 Page 2 Cat.26 Final.qxp_2020 31/08/2020 19:54 Page 3 1 Unknown The Death of Buddha. Circa 1700-1710. Hand-coloured sumizuri-e. Kakemono-e. 51.7 x 28.3 cm. Vever/I/62. Very good impression with extensive brass dusting and traces of applied gum. Toned, otherwise very good condition. Roger Keyes believes this to be the earliest version of which there are two later examples with completely different blocks by Shigenobu and Shigenaga (Ainsworth Collection, Oberlin, 1984, pages 115-116, and 136). These are dated to the 1730’s-1740’s. Keyes lists the Vever impression which is similar to ours and illustrates the example in the Cleveland Museum of Art which lacks the metallic dust, but is also from the same blocks. Cat.26 Final.qxp_2020 31/08/2020 19:54 Page 4 Cat.26 Final.qxp_2020 31/08/2020 19:54 Page 5 2 Okumura Masanobu (1686-1764) A Patron in a Brothel Reclining with Male and Female Prostitutes.The First Month. From the series (Someiro no yama) Neya no hinagata (Mountains of Dyed Colours: Patterns for the Bedroom). Circa 1740. Hand-coloured sumizuri-e. Oban. 27.4 x 35.9 cm. Clark, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, British Museum, no. -

Heart of Japan 2016 08

Heart of Japan Collection of Essays from the Annual Japan Center Essay Competition (2005-2015) © The Japan Center at Stony Brook 2016 The Japan Center at Stony Brook Stony Brook University Stony Brook, NY 11794-5343 stonybrook.edu/japancenter [email protected] * The authors of the essays in this collection granted their copyrights to the Japan Center at Stony Brook. Printed by: Century Direct 15 Enter Lane Islandia,NY 11749 Contents Forward iv Preface v Acknowledgments vi Key Personnel viii Selected Essays 1 Memorable Moments 105 People 117 Epilogue 140 iii Foreword I extend my warmest congratulations and gratitude to the Japan Center at Stony Brook University for publishing this wonderful compilation of the selected essays from its 10 years of Essay Competitions. Through their participation, students had been given the opportunity to explore their interest in Japan, which can now be shared with readers far and wide. I hope many will find these essays a joy to read, as I have. With sincere appreciation, Reiichiro Takahashi Ambassador and Consul General of Japan in New York I would like to offer my appreciation to the Japan Center at Stony Brook University and all of the students involved with this wonderful program. As a global company and proud sponsor of the essay competition, Canon has been delighted to engage with so many young people who have expressed how Japan has positively influenced their life in one way or another. We recognize the enormous importance of uniting cultures and opening the minds of those who are the future of our world. Congratulations to all of the students! Sincerely, Joe Adachi Chairman & CEO, Canon U.S.A., Inc. -

Japanese Prints Surimono and Paintings

Japanese Prints Surimono and Paintings LELLA & GIANNI MORRA Catalogue 11 Lella & Gianni Morra Giudecca 699 30133 Venezia Italy Tel. & Fax: +39 041 528 8006 Mobile: +39 333 471 9907 (by appointment only) E-mail: [email protected] www.morra-japaneseart.com Acknowledgements: Many thanks to our friends: Giglia Bragagnini for the translation from Japanese, John Fiorillo for information on painting no. 67, Mattia Biadene for the catalogue layout and Ampi-chan for her patience. Japanese Prints, Surimono and Paintings LELLA & GIANNI MORRA Fine Japanese Prints and Illustrated Books 1. Suzuki Harunobu (1725?-1770) Two lovers. From a series of erotic prints, ca. 1768. Signed on the screen in the foreground Harunobu ga. Format chuban, 19,4x25,3 cm. 2. Kitao Masanobu (1761-1816) Two lovers and a the sleeping hausband. From a series of erotic prints, ca. 1785. Unsigned as all prints in the series. Format chuban, 18x25,6 cm. 3. Kitao Masanobu (1761-1816) Two lovers near a kotatsu. From the same series as last, ca. 1785. Unsigned. Format chuban, 19,2x25,1 cm. 4. Katsukawa Shuncho (active ca. 1780-1800) Two lovers. From the series of erotic prints Shikido shusse kagami (Mirror of the Excellent Love Path) ca. 1790-5. Unsigned as all prints in the series. Format chuban, 18,5x24,7 cm. 5. Katsukawa Shuncho (active ca. 1780-1800) Two lovers. From an untitled series of erotic prints published in 1797. Unsigned as all prints in the series. Format oban, 25,3x37,5 cm. Another impression is illustrated in Kobayashi and Shirakura, p. 203. 6. Kitagawa Utamaro (1753?-1806) A courtesan and her lover seated on a bench in a summer evening. -

Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism: Myōshinji, a Living Religion

Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd i 12/20/2007 6:19:39 PM Numen Book Series Studies in the History of Religions Series Editors Steven Engler (Mount Royal College, Canada) Richard King (Vanderbilt University, U.S.A.) Kocku von Stuckrad (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Gerard Wiegers (Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands) VOLUME 119 BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd ii 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM Japanese Rinzai Zen Buddhism Myōshinji, a living religion By Jørn Borup LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd iii 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM On the cover: Myōshinji honzan in Kyoto. Photograph by Jørn Borup. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISSN 0169-8834 ISBN 978 90 04 16557 1 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd iv 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM For Marianne, Mads, and Sara BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd v 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM BORUP_f1_i-xii.indd vi 12/20/2007 6:19:40 PM CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................... -

JICC Teaching Tuesday: Kotatsu

KOTATSU Unlike many Western homes, Japanese dwellings are not equipped with central air and heating. During the winter, space heaters are the most common warming element, but another popular way to keep warm is the kotatsu 炬燵. A low table with a wooden frame, the kotatsu is covered by a kotatsugake (火燵掛布 kotatsu futon) to trap in heat from the heater built in under the table. Kotatsu tables weren’t originally tables. In the 14th century, the original heating element was the irori 囲炉裏, a charcoal powered hearth that also served as a stove. People enhanced the irori by placing a wooden plat- form with a blanket on top to separate the cooking areas from the seating, and trap the heat under the platform. This became known as a hori-kotat- su 掘り炬燵, where ko 炬 means fire and tatsu 燵 means foot warmer. The design was changed in the Edo period with the invention of the sunken irori, which involved digging out the ground in a square shape and placing the platform and blanket on top. The portable kotatsu started at the end of the 17th century, as tatami mats became popular. A charcoal pot was placed under the table on top of the tatami, making it easy to move the kotatsu everywhere. This was originally called oki-gotatsu 置き炬燵 with oki 置き meaning placement. Now, with electricity, heating elements are built into the frame, the kotatsu is completely portable, and a popular way to stay warm. Other elements of a kotatsu include a shitagake 下掛け (a blanket goes under kotatsugake), a zabuton 座布団 (oversized pillow use to sit on), and a kotatsushiki こたつ敷き (rug). -

The Ondol Problem and the Politics of Forest Conservation in Colonial Korea David Fedman

The Ondol Problem and the Politics of Forest Conservation in Colonial Korea David Fedman This article examines the ondol—the cooking stove–cum–heated floor system conven- tional to Korean dwellings—as a site of contestation over forest management, fuel consumption, and domestic life in colonial Korea. At once a provider of heat essential to survival in an often frigid peninsula and, in the eyes of colonial officials, ground zero of deforestation, the ondol garnered tremendous interest from an array of reformers determined to improve the Korean home and its hearth. Foresters were but one party to a far-reaching debate (involving architects, doctors, and agrono- mists) over how best to domesticate heat in the harsh continental climate. By tracing the contours of this debate, this article elucidates the multitude of often-conflicting interests inherent to state-led interventions in household fuel economies: what the au- thor calls the politics of forest conservation in colonial Korea. In focusing on efforts to regulate the quotidian rhythms of energy consumption, it likewise investigates the material underpinnings of everyday life—a topic hitherto overlooked in extant schol- arship on forestry and empire alike. Keywords: ondol, forestry, fuel, architecture Few fixtures of Koreans’ everyday life elicited as much comment from sojourners to turn-of-the-century Korea as the ondol (literally, warm stone), the cooking stove– cum–radiant-heated floor system used in homes across the country. Like the white garments traditionally worn by Koreans, the ondol was routinely high- lighted as a distinctive feature of life in the often frigid peninsula, where the David Fedman is assistant professor of Japanese and Korean history at the University of California, Irvine.