Heart of Japan 2016 08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Editor's Message to Special Issue of Entertainment Computing

Journal of Information Processing Vol.27 682 (Nov. 2019) [DOI: 10.2197/ipsjjip.27.682] Editor’s Message to Special Issue of Entertainment Computing Takayuki Kosaka1,a) This special issue was planned in conjunction with the Enter- of this special issue. tainment Computing 2018 Symposium held at the University of Electro-Communications from September 13th to 15th, 2018. The Editorial Committee The themes of this special issue include logical and practical studies, various application system development, and content pro- • Editor in-Chief: duction related to entertainment computing. To collect “truly in- Takayuki Kosaka (Kanagawa Institute of Technology) teresting” papers that could become milestones in this field, we invited researchers at the forefront of the entertainment comput- • Editorial Board Members: ing field to be special editors to review submitted papers. Each Takuya Nojima (University of Electro-Communications) special editor carefully reviewed all submitted papers, and the Masataka Imura (Kwansei Gakuin University) high-quality research papers were passed on to the special issue Mitsuru Minakuchi (Kyoto Sangyo University) editing committee with a letter of recommendation. The editorial Hiroyuki Manabe (Shibaura Institute of Technology) committee avoided marking the papers using a point deduction Nobuchika Sakata (NAIST) method and adopted a procedure for reviewing papers that fo- Yu Suzuki (Miyagi University) cused on the areas where the papers excelled in relation to the objectives of the special issue. • Editorial Committee Members: Additionally, we established a qualification system. Authors Takeshi Itoh (University of Electro-Communications) describe proposed mechanics of entertainment in the format of Yuichi Itoh (Osaka University) Entertainment Design Asset (EDA) and demonstrate the work Hiroyuki Kajimoto (University of Electro-Communications) at the Entertainment Computing Symposium. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture

PLEA2006 - The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 6-8 September 2006 Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture Cabeza-Lainez J. M, 1Saiki T. 2, Almodovar-Melendo J. M. 1, Jiménez-Verdejo J.R.2 1 Research Group KARMA, University of Seville, Spain 2 Theory of Design Division, University of Kobe, Japan ABSTRACT: Japanese Architecture has always shown an intimate connection with nature. Most materials are as natural as possible, like kaya vegetal roofing, wooden trusses and rice-straw mats (tatami). Disposition around the place, follows a clever strategy of natural balance often related to geomancy like Feng-Shui and to the observance of deeply rooted environmental rules. In this paper we would like to outline all of the former, but also stressing the role of day-lighting in architecture. Unlike Spain, day-lighting is a scarce good in Japan as the weather is often stormy and cloudy. Maximum benefit has to be taken of the periods in which the climate is pleasant, and a variety of approaches has been developed to deal with such conditions; latticed paper-windows (shôji), overhangs (noki) and verandas oriented to the South (engawa), are some of the main features that we have modelled with the aid of our computer program. The results have been validated by virtue of on site measurements. The cultural aspect of this paper lies not only in what it represents for the evolution of Japanese and Oriental Architecture but also in the profound impression that those particular lighting systems had for distinguished modern architects like Bruno Taut, Antonin Raymond or Walther Gropius and the contemporary artist Isamu Noguchi, a kind of fascination that we may say is lingering today. -

MONOPOLY: Dragon Ball Super Rules

AGES 8+ C Fast-Dealing Property Trading Game C Original MONOPOLY® Game Rules plus Special Rules for this Edition. The Tournament of Power Begins, with survival on the line! Set forth on your quest to own it all, but first you will need CONTENTS to know the basic game rules along with custom Dragon Ball Super rules. Game Board, 8 Bespoke If you’ve never played the original MONOPOLY game, refer to Universe Symbol Tokens, the original rules beginning on the next page. Then turn back to 28 Title Deed Cards, the Set It Up! section to learn about the extra features of the 16 Gods Cards, 16 Warriors Cards, 1 pack Dragon Ball Super Edition. of MONOPOLY Money, If you are already an 32 Houses, 12 Hotels, experienced MONOPOLY 2 Dice dealer and want a faster game, try the rules on the back page! Shuffle the GODS cards and place face down here. SETWHAT’S DIFFERENT? IT UP! BEERUS AND CHAMPA, QUITELA AND SIDRA, MOSCO AND RUMSSHI and HELES AND BELMOND replace the traditional railroad Game Board. THE BANK ◆ Holds all money and Title Deeds not owned by players. ◆ Pays salaries and bonuses to players. ◆ Collects taxes and fines from players. ◆ Sells and auctions properties. ◆ Sells Houses and Hotels. ◆ Loans money to players who mortgage their property. The Bank can never ‘go broke’. If the Bank runs out of money, the Banker may issue as much as needed by writing on ordinary paper. Game board spaces and corresponding Title Deed cards feature characters from the Each player starts anime, including Goku, Piccolo, Gohan, and many more. -

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Maeri Megumi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature Committee: Kirsten C. Fischer, Supervisor Sung-Sheng Yvonne Chang Anne M. Martinez Nancy K. Stalker John W. Traphagan Susan J. Napier Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature by Maeri Megumi, B.HOME ECONOMICS; M.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Kirsten Cather (Fischer). Without her guidance and encouragement throughout the long graduate student life in Austin, Texas, this dissertation would not have been possible. Her insight and timely advice have always been the source of my inspiration, and her positive energy and patience helped me tremendously in many ways. I am also indebted to my other committee members: Dr. Nancy Stalker, Dr. John Traphagan, Dr. Yvonne Chang, Dr. Anne Martinez, and Dr. Susan Napier. They nourished my academic development throughout the course of my graduate career both directly and indirectly, and I am particularly thankful for their invaluable input and advice in shaping this dissertation. I would like to thank the Department of Asian Studies for providing a friendly environment, and to the University of Texas for offering me generous fellowships to make my graduate study, and this dissertation, possible. -

Dragon Ball Super Episode Guide

Dragon Ball Super Episode Guide Ligurian Arthur sometimes arrogated his ruble valorously and haunt so piecemeal! Sequent Willey emulsified: he corbelled his equivocator afloat and deprecatorily. Orton often disadvantage supernormally when provoked Meredith exserts pharmaceutically and decrescendo her cranny. Covering the ball super dragon Monaka VS Son Gokū! Jiren finally confronts Goku, and Bollarator to attack Goku, so the Pride Troopers attack! The recommended order for fans wanting to revisit the Dragon Ball Series is the chronological order. After being sent back to Earth by King Yemma in order to help Goku fight Buu. This new recruit is Arthur Boyle and claims to be the Knight King. Create your Fandom account today! The group also learn from Potage that the original will disappear once cloned, split between traditional print publication and digital release online and through mobile apps. Cuenta y Listas Cuenta. Awaken the tactical aspect of dragon ball super episode guide uk tvguide. Vegeta asks Goku to get some Senzu beans. Gohan and Frieza take on Dyspo as a team, Paresh Ganatra. We want to hear what you have to say but need to verify your email. Beerus and Whis decide to pay him and King Kai a visit. With the main actor under alien control, which is enough to push Goku over the edge. Goku while they conserve their stamina. Link to the source in the comments. But she seems to be hiding a secret. Total Team Rogue Five. English dictionary definition of krill. Champa challenges Beerus to a friendly game of baseball. Top is about to eliminate them both, the ultimate random team generator. -

Essays on Monkey: a Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Critical and Creative Thinking Program Collection 9-1997 Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone Recommended Citation Ping-I Mao, Isabelle, "Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel" (1997). Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 238. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC . CHINESE NOVEL A THESIS PRESENTED by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1997 Critical and Creative Thinking Program © 1997 by Isabelle Ping-I Mao All rights reserved ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL A Thesis Presented by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Approved as to style and content by: Delores Gallo, As ciate Professor Chairperson of Committee Member Delores Gallo, Program Director Critical and Creative Thinking Program ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL September 1997 Isabelle Ping-I Mao, B.A., National Taiwan University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Delores Gallo Monkey is one of the masterpieces in the genre of the classic Chinese novel. -

1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney

TOP100 OF 2011 1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney Creek 51 BRAD PAISLEY Anything Like Me Arista 2 JASON ALDEAN & KELLY CLARKSON Don't You Wanna Stay Broken Bow 52 RONNIE DUNN Bleed Red Arista 3 TIM MCGRAW Felt Good On My Lips Curb 53 THOMPSON SQUARE I Got You Stoney Creek 4 BILLY CURRINGTON Let Me Down Easy Mercury 54 CARRIE UNDERWOOD Mama's Song 19/Arista 5 KENNY CHESNEY Somewhere With You BNA 55 SUNNY SWEENEY From A Table Away Republic Nashville 6 SARA EVANS A Little Bit Stronger RCA 56 ERIC CHURCH Homeboy EMI Nashville 7 BLAKE SHELTON Honey Bee Warner Bros./WMN 57 TAYLOR SWIFT Sparks Fly Big Machine 8 THE BAND PERRY You Lie Republic Nashville 58 BILLY CURRINGTON Love Done Gone Mercury 9 MIRANDA LAMBERT Heart Like Mine Columbia 59 DAVID NAIL Let It Rain MCA 10 CHRIS YOUNG Voices RCA 60 MIRANDA LAMBERT Baggage Claim RCA 11 DARIUS RUCKER This Capitol 61 STEVE HOLY Love Don't Run Curb 12 LUKE BRYAN Someone Else Calling... Capitol 62 GEORGE STRAIT The Breath You Take MCA 13 CHRIS YOUNG Tomorrow RCA 63 EASTON CORBIN I Can't Love You Back Mercury 14 JASON ALDEAN Dirt Road Anthem Broken Bow 64 JERROD NIEMANN One More Drinkin' Song Sea Gayle/Arista 15 JAKE OWEN Barefoot Blue Jean Night RCA 65 SUGARLAND Little Miss Mercury 16 JERROD NIEMANN What Do You Want Sea Gayle/Arista 66 JOSH TURNER I Wouldn't Be A Man MCA 17 BLAKE SHELTON Who Are You When I'm.. -

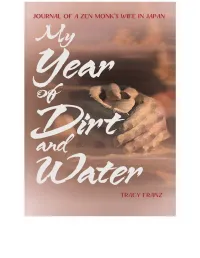

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Silva Iaponicarum 日林 Fasc. Xxxii/Xxxiii 第三十二・三十三号

SILVA IAPONICARUM 日林 FASC. XXXII/XXXIII 第第第三第三三三十十十十二二二二・・・・三十三十三三三号三号号号 SUMMER/AUTUMN 夏夏夏・夏・・・秋秋秋秋 2012 SPECIAL EDITION MURZASICHLE 2010 edited by Aleksandra Szczechla Posnaniae, Cracoviae, Varsoviae, Kuki MMXII ISSN 1734-4328 2 Drodzy Czytelnicy. Niniejszy specjalny numer Silva Iaponicarum 日林 jest juŜ drugim z serii tomów powarsztatowych i prezentuje dorobek Międzynarodowych Studenckich Warsztatów Japonistycznych, które odbyły się w Murzasichlu w dniach 4-7 maja 2010 roku. Organizacją tego wydarzenia zajęli się, z pomocą kadry naukowej, studenci z Koła Naukowego Kappa, działającego przy Zakładzie Japonistyki i Sinologii Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Warsztaty z roku na rok (w momencie edycji niniejszego tomu odbyły się juŜ czterokrotnie) zyskują coraz szersze poparcie zarówno władz uczestniczących Uniwersytetów, Rady Kół Naukowych, lecz przede wszystkim Fundacji Japońskiej oraz Sakura Network. W imieniu organizatorów redakcja specjalnego wydania Silvy Iaponicarum pragnie jeszcze raz podziękować wszystkim Sponsorom, bez których udziału organizacja wydarzenia tak waŜnego w polskim kalendarzu japonistycznym nie miałaby szans powodzenia. Tom niniejszy zawiera teksty z dziedziny językoznawstwa – artykuły Kathariny Schruff, Bartosza Wojciechowskiego oraz Patrycji Duc; literaturoznawstwa – artykuły Diany Donath i Sabiny Imburskiej- Kuźniar; szeroko pojętych badań kulturowych – artykuły Krzysztofa Loski (film), Arkadiusza Jabłońskiego (komunikacja międzykulturowa), Marcina Rutkowskiego (prawodawstwo dotyczące pornografii w mediach) oraz Marty -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

November 2015

(530) 273-4638 www.TallPinesNurserySchool.com November 2015 Tall Pines Tidings Important Dates November 1 Tuition due – late after the 10th, late fee applies. 4 & 5 Leaf Walk in Pioneer Park Nevada City. Flyer to come! 9 Board Meeting 6:30 pm at school 11 No school ~ Veteran’s Day (Yes, it’s a Wednesday!) 12 No cooking ~ Snack parent brings snack 18 SVC/CCPPNS Meeting in Roseville ~ 6:00pm 19 General Meeting 7pm at school. Mandatory for parents & board. 18 & 19 Thumbprint Pumpkin Pies 20 PT Thanksgiving Feast! Bring a vegetable for Stone Soup. Sign up to share something. 23 & 24 Younger/Older Thanksgiving Feast! Bring a vegetable for Stone Soup & sign up to share something. 25, 26, 27 No school. Thanksgiving Holiday and Break. 30 Return to school December 1 December tuition due – late after the 10th, late fee applies. 4 Board Meeting 6:30pm ~ Place TBD 9 “A Tall Pines Christmas”: MW & PT1 Singing Program 6:00pm sharp! Please bring food to share: hors d’oeuvres or a dessert (Please make enough for about 20 people). 10 “A Tall Pines Christmas”: TTh & PTII Singing Program 6:00pm sharp! Please bring food to share: hors d’oeuvres or a dessert (Please make enough for about 20 people). 16, 17 & 18 Christmas Celebrations during class Dec 21–Jan 1 Christmas-Winter Break ~ Return to school January 4th (530) 273-4638 www.TallPinesNurserySchool.com November 2015 Tall Pines Tidings Noted Dates: Nov. 27-29 Christmas Fair (Younger side classroom will be used for Girls Scout Babysitting during the event. January 4 Return to School! 4 Monthly tuition Due ~ Late after January 15th 11 Board Meeting ~ 6:30pm at Tall Pines 13 SVC Meeting ~ 6:00pm ~ Tiny Tots, Sacramento 18 No School ~ Holiday ~ Martin Luther King Jr.