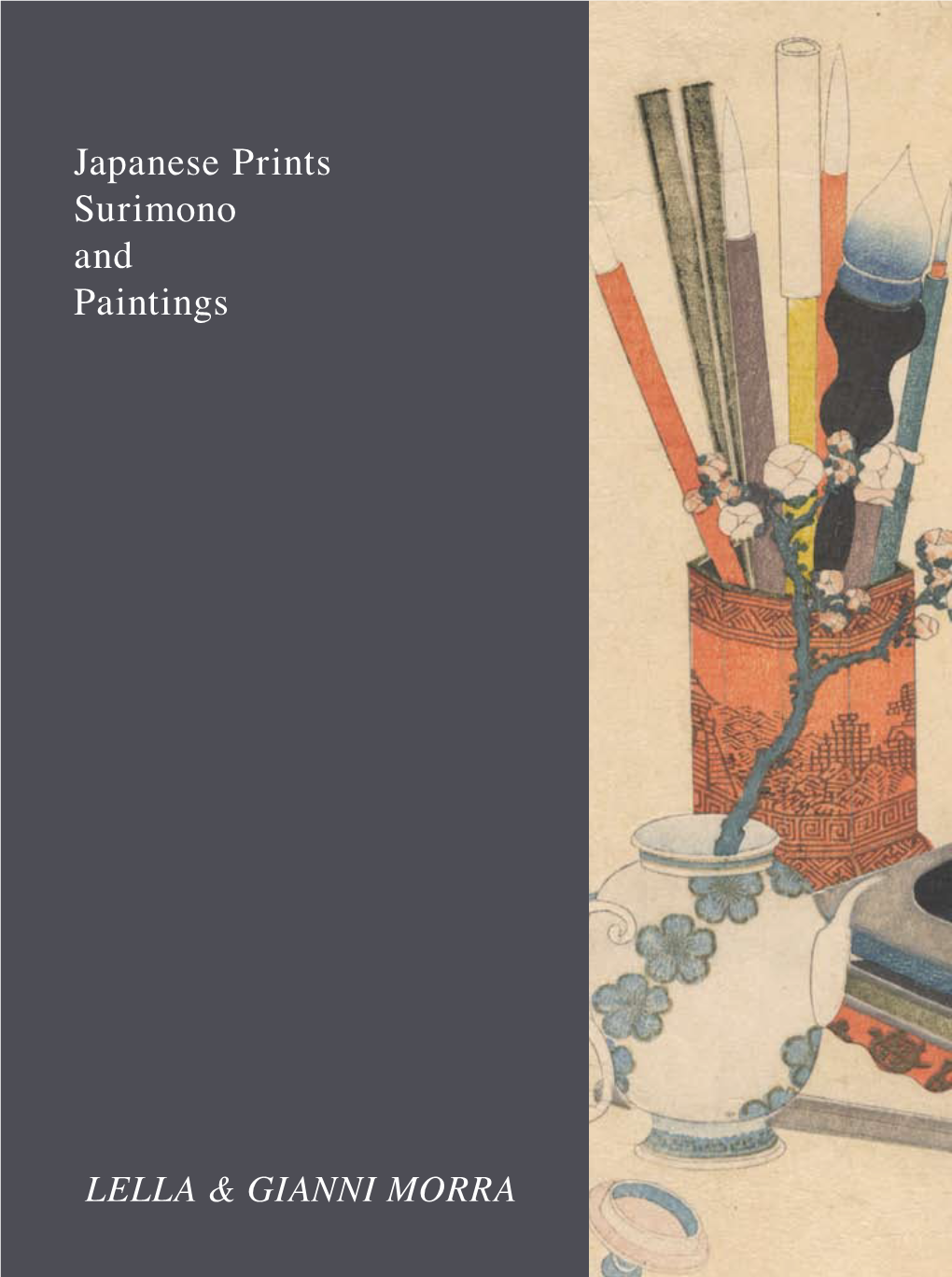

Japanese Prints Surimono and Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Checklist

Mountains and Rivers: Scenic Views of Japan, July 10, 2009-November 1, 2009 The landscape has long been an important part of Japanese art and literature. It was first celebrated in poetry, where invoking the name of a famous location, or meisho, was meant to summon a certain feeling. Later, paintings of these same locations would bring to mind their well-known poetic and literary history. Together, the poems and imagery comprised a canon of place and sentiment, as the same meisho were rendered again and again. During the Edo period (1603–1868) the landscape genre, initially available only to the elite, spread to the medium of woodblock printing, the art of commoner culture. In the 19th century, when most of the works in this exhibition were made, several factors led to the rise of the landscape genre in woodblock prints. Up to this time, the staples of the woodblock print medium had been images of beautiful courtesans and handsome kabuki theater actors. First among these factors was the rising popularity of domestic travel. The development of a system of major roads allowed many people to travel for both business and pleasure. Woodblock prints of locations along these travel routes could function as souvenirs for those who made the trip or as fantasy for those who could not. Rather than evoking a poetic past, these images of meisho were meant to tantalize viewers into imagining romantic far-off places. Another factor in the growth of the genre was the skill of two particular woodblock print artists— Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) (whose works are heavily represented here). -

Seduction: Japan's Floating World Transports Viewers to the Popular and Enticing Entertainment Districts Established in Edo (Present- Day Tokyo) in the Mid-1600S

PRESS CONTACTS: Tim Hallman Annie Tsang 415.581.3711 415.581.3560 [email protected] [email protected] SEDUCTION: JAPAN’S FLOATING WORLD Escape to Japan’s floating world through a selection of rare paintings, woodblock prints and kimonos at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum SAN FRANCISCO, Feb. 13, 2015—Seduction: Japan's Floating World transports viewers to the popular and enticing entertainment districts established in Edo (present- day Tokyo) in the mid-1600s. Through more than 50 artworks from the acclaimed John C. Weber Collection, visitors can encounter the alluring realm known as the “floating world,” notably its famed pleasure quarter, the Yoshiwara. Masterpieces of painting, luxurious Japanese robes, woodblock-printed guides and decorative arts tell the story of how the art made to represent Edo’s seductive courtesans, flashy Kabuki actors and extravagant customs gratified fantasies and fueled desires. At a time when a strict social hierarchy regulated most aspects of the samurai and townsmen’s lives, the floating world provided a temporary escape. The term “floating world,” or ukiyo, originated from a common Buddhist phrase referring to the suffering of the physical world, which was inverted to signify a realm of boundless indulgence. Both a state of mind and a set of locales, the floating world refers to the diversions available in the brothel districts and Kabuki theaters of Edo, a city whose population had reached a million by the beginning of the 18th century. The floating world’s rise to prominence gave birth to an outpouring of new artistic production, in the form of paintings and woodblock prints that advertised celebrities and spread knowledge of the city’s famous theaters and brothels. -

The Sexual Life of Japan : Being an Exhaustive Study of the Nightless City Or the "History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku"

Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924012541797 Cornell University Library HQ 247.T6D27 1905 *erng an exhau The sexual life of Japan 3 1924 012 541 797 THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN BEING AN EXHAUSTIVE STUDY OF THE NIGHTLESS CITY 1^ ^ m Or the "HISTORY of THE YOSHIWARA YUKWAKU " By J, E. DE BECKER "virtuous men hiive siitd, both in poetry and ulasslo works, that houses of debauch, for women of pleasure and for atreet- walkers, are the worm- eaten spots of cities and towns. But these are necessary evils, and If they be forcibly abolished, men of un- righteous principles will become like ravelled thread." 73rd section of the " Legacy of Ityasu," (the first 'I'okugawa ShOgun) DSitl) Niimrraiia SUuatratiuna Privately Printed . Contents PAGE History of the Yosliiwara Yukwaku 1 Nilion-dzutsumi ( 7%e Dyke of Japan) 15 Mi-kaeri Yanagi [Oazing back WUlow-tree) 16 Yosliiwara Jiuja ( Yoahiwara Shrine) 17 The "Aisome-zakura " {Chen-y-tree of First Meeting) 18 The " Koma-tsunagi-matsu " {Colt tethering Pine-tree) 18 The " Ryojin no Ido " {Traveller's Well) 18 Governmeut Edict-board and Regulations at the Omen (Great Gate) . 18 The Present Omon 19 »Of the Reasons why going to the Yosliiwara was called " Oho ve Yukn " ". 21 Classes of Brothels 21 Hikite-jaya (" Introducing Tea-houses"') 28 The Ju-hachi-ken-jaya (^Eighteen Tea-houses) 41 The " Amigasa-jaya -

Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture

PLEA2006 - The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzerland, 6-8 September 2006 Lighting Features in Japanese Traditional Architecture Cabeza-Lainez J. M, 1Saiki T. 2, Almodovar-Melendo J. M. 1, Jiménez-Verdejo J.R.2 1 Research Group KARMA, University of Seville, Spain 2 Theory of Design Division, University of Kobe, Japan ABSTRACT: Japanese Architecture has always shown an intimate connection with nature. Most materials are as natural as possible, like kaya vegetal roofing, wooden trusses and rice-straw mats (tatami). Disposition around the place, follows a clever strategy of natural balance often related to geomancy like Feng-Shui and to the observance of deeply rooted environmental rules. In this paper we would like to outline all of the former, but also stressing the role of day-lighting in architecture. Unlike Spain, day-lighting is a scarce good in Japan as the weather is often stormy and cloudy. Maximum benefit has to be taken of the periods in which the climate is pleasant, and a variety of approaches has been developed to deal with such conditions; latticed paper-windows (shôji), overhangs (noki) and verandas oriented to the South (engawa), are some of the main features that we have modelled with the aid of our computer program. The results have been validated by virtue of on site measurements. The cultural aspect of this paper lies not only in what it represents for the evolution of Japanese and Oriental Architecture but also in the profound impression that those particular lighting systems had for distinguished modern architects like Bruno Taut, Antonin Raymond or Walther Gropius and the contemporary artist Isamu Noguchi, a kind of fascination that we may say is lingering today. -

For Use Only the Library

FOR USE ONLY I THE LIBRARY preliminary catalogue of the Japanese prints and othe illustrations in the Library of the School of Oriental & African Studies By s. Matsudaira The Library 1972 {_ '("' ( '2. -.3r - ,., ,. ... - ,.,. \ r-.1' ')\ SI c -,:-,..:_1) /' J J L INDEX OF JAPliliESE PRINTS & OTHER ITEMS KEY 1. Artist's name 2. Size (in centinetres) and shape of print 3. Description 4. Title (series and individual) 5. Publisher 6. Censor seal, kiwame seal, year-date seal 7. Signature 8. Date 9. References, etc. ( .... /{,_ 8/ y --7 I ') - (1 4t '1. ANONYMOUS '1 - '1 '1 • (Anonymous) 2. Oban. 23.6 x 35.8 3. At the gate of a red-light district ( it might be Shinagawa), two maidservants guiding a customer; another two are waiting for the arrival of their customer. 4. None 5. None 6. None 7. None 8. ea ,'1820 9. '1 - 2 - 3 1. Anonymous) 2. Oban. 37.0 x 25.2. 2ptych. (A set from, a series?) 3. Singing instructor's room. People learning short songs - "Dodoitsu". 4. Title: TOsei misuji no tanoshimi (Enjoyment a la mode with a three-stringed instrument). 5. None 6. None 7. None 8. ea 1850 9. 1 - 4 1. (Anonymous) 2. Oban. 38.0 x 25.8 3. Minamoto Yoshiie, in 1063, releasing 1000 cranes with golden tags tied to their legs at the top of Mt. Kamakura so that the Genji family might prosper for a long time. 4. None 5. Nishimura Yohachi 6. Kiwame seal 7. None 8. ea '1840 9. 1 - 5 1. (Anonymous) 2. -

Chapter5: Ainsworth's Beloved Hiroshige

No. Artist Title Date Around Tenpō 14-Kōka 1 150 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Min Zigian (Binshiken), from the series A Mirror for Children of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (c.1843-44) 151 Utagawa Kuniyoshi The Ghosts of the Slain Taira Warriors in Daimotsunoura Bay Around Kaei 2-4 (c.1849-51) Around Tenpō 14-Kōka 3 152 Keisai Eisen View of Kegon Waterfall, from the series Famous Places in the Mountains of Nikkō (c.1843-46) Chapter5: Ainsworth's Beloved Hiroshige 153 Utagawa Hiroshige Leafy Cherry Trees on the Sumidagawa River, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital Around Tenpō 2 (c.1831) 154 Utagawa Hiroshige First Cuckoo of the Year at Tsukuda Island, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital Around Tenpō 2 (c.1831) Clearing Weather at Awazu, Night Rain at Karasaki, Autumn Moon at Ishiyamadera Temple, Descending 155-162 Utagawa Hiroshige Geese at Katada, Sunset Glow at Seta, Returning Sails at Yabase, Evening Bell at Mii–dera Temple, Around Tenpō 2-3 (c.1831-32) Evening Snow at Hira, from the series Eight Views of Ōmi 163-164 Utagawa Hiroshige Morning Scene of Nihonbashi Bridge, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5 (c.1834) 165 Utagawa Hiroshige A Procession Sets Out at Nihonbashi Bridge, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5-6 (c.1834-35) 166 Utagawa Hiroshige Morning Mist at Mishima, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5 (c.1834) 167 Utagawa Hiroshige Twilight at Numazu, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5-6 (c.1834-35) 168 Utagawa Hiroshige Mt. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Plant Dye Identification in Japanese Woodblock Prints

Plant Dye Identification in Japanese Woodblock Prints Michele Derrick, Joan Wright, Richard Newman oodblock prints were first pro- duced in Japan during the sixth Wto eighth century but it was not until the Edo period (1603–1868) that the full potential of woodblock printing as a means to create popular imagery for mass consumption developed. Known broadly as ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the float- ing world,” these prints depicted Kabuki actors, beautiful women, scenes from his- tory or legend, views of Edo, landscapes, and erotica. Prints and printed books, with or without illustrations, became an inte- gral part of daily life during this time of peace and stability. Prints produced from about the 1650s through the 1740s were printed in black line, sometimes with hand-applied color (see figure 1). These col- ors were predominantly mineral (inorganic) pigments supplemented by plant-based (organic) colorants. Since adding colors to a print by hand was costly and slowed pro- duction, the block carvers eventually hit upon a means to create a multicolor print using blocks that contained an “L” shaped groove carved into the corner and a straight groove carved further up its side in order to align the paper to be printed (see figure 2). These guides, called kento, are located Figure 1. Actors Sanjō Kantarō II and Ichimura Takenojō IV, (MFA 11.13273), about 1719 (Kyōho 4), designed by Torii Kiyotada I, and published by in the same location on each block. They Komatsuya (31.1 x 15.3 cm). Example of a beni-e Japanese woodblock ensure consistent alignment as each color print with hand-applied color commonly made from the 1650s to 1740s. -

Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige Contemporary Landscapes Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese: 歌川 広重), also Andō Hiroshige (Japanese: 安藤 広重; 1797 – 12 October 1858) was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition. Hiroshige is best known for his landscapes, such as the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō; and for his depictions of birds and flowers. The subjects of his work were atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose typical focus was on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868). The popular Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series by Hokusai was a strong influence on Hiroshige's choice of subject, though Hiroshige's approach was more poetic and ambient than Hokusai's bolder, more formal prints. For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Hiroshige's work came to have a marked influence on Western painting towards the close of the 19th century as a part of the trend in Japonism. Western artists closely studied Hiroshige's compositions, and some, such as van Gogh, painted copies of Hiroshige's prints. Hiroshige was born in 1797 in the Yayosu Quay section of the Yaesu area in Edo (modern Tokyo).[1] He was of a samurai background,[1] and was the great-grandson of Tanaka Tokuemon, who held a position of power under the Tsugaru clan in the northern province of Mutsu. -

Comparison of the “Oki-Gotatsu” in the Traditional Japanese House and the “Kürsü” in the Traditional Harput House

Intercultural Understanding, 2019, volume 9, pages 15-19 Comparison of the “Oki-gotatsu” in the Traditional Japanese House and the “Kürsü” in the Traditional Harput House ølknur Yüksel Schwamborn1 1 Architect, østanbul, Turkey Corresponding author: ølknur Yüksel Schwamborn, Architect, østanbul, Turkey, E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Japan, kotatsu, oki-gotatsu, Turkey, Anatolia, Harput, kürsü, table, heater Abstract: The use of the wooden low table “kotatsu” in the center of the traditional Japanese house in the seventeenth century (Edo (Tokugava) period), the oki-gotatsu, is similar to the use of the wooden low table in the traditional Harput house, the “kürsü”. The “kotatsu” and the “kürsü” used in winter in both places with similar climate characteristics are the table usage, which is collected around the place and where the warm-up needs are met. The origins of these similar uses in the traditional Japanese house and the traditional Harput house, located in different and distant geographies, can be traced back to Central Asia. In this study, the shape and use characteristics of “oki-gotatsu”, a form of traditional Japanese house in the past, and the shape and use characteristics of the “kürsü” in the traditional Harput house are compared. 1. Introduction area is exposed to northern and southern air currents and dominated by a cold climate, which makes life conditions In this study the traditional Japanese house wooden low table difficult. (Kahraman, 2010) Continental, polar-like air masses "kotatsu" is compared with the traditional Harput house "kürsü" originating from the inner parts of Asia move southwest before known from Turkey.