Fragile Beauty Historic Japanese Graphic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timely Timeless.Indd 1 2/12/19 10:26 PM Published by the Trout Gallery, the Art Museum of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 17013

Timely and Timeless Timely Timely and Timeless Japan’s Modern Transformation in Woodblock Prints THE TROUT GALLERY G38636_SR EXH ArtH407_TimelyTimelessCover.indd 1 2/18/19 2:32 PM March 1–April 13, 2019 Fiona Clarke Isabel Figueroa Mary Emma Heald Chelsea Parke Kramer Lilly Middleton Cece Witherspoon Adrian Zhang Carlisle, Pennsylvania G38636_SR EXH ArtH407_Timely Timeless.indd 1 2/12/19 10:26 PM Published by The Trout Gallery, The Art Museum of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 17013 Copyright © 2019 The Trout Gallery. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from The Trout Gallery. This publication was produced in part through the generous support of the Helen Trout Memorial Fund and the Ruth Trout Endowment at Dickinson College. First Published 2019 by The Trout Gallery, Carlisle, Pennsylvania www.trougallery.org Editor-in-Chief: Phillip Earenfight Design: Neil Mills, Design Services, Dickinson College Photography: Andrew Bale, unless otherwise noted Printing: Brilliant Printing, Exton, Pennsylvania Typography: (Title Block) D-DIN Condensed, Brandon Text, (Interior) Adobe Garamond Pro ISBN: 978-0-9861263-8-3 Printed in the United States COVER: Utagawa Hiroshige, Night View of Saruwaka-machi, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (detail), 1856. Woodblock print, ink and color on paper. The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA. 2018.3.14 (cat. 7). BACK COVER: Utagawa Hiroshige, Night View of Saruwaka-machi, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (detail), 1856. -

Seduction: Japan's Floating World Transports Viewers to the Popular and Enticing Entertainment Districts Established in Edo (Present- Day Tokyo) in the Mid-1600S

PRESS CONTACTS: Tim Hallman Annie Tsang 415.581.3711 415.581.3560 [email protected] [email protected] SEDUCTION: JAPAN’S FLOATING WORLD Escape to Japan’s floating world through a selection of rare paintings, woodblock prints and kimonos at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum SAN FRANCISCO, Feb. 13, 2015—Seduction: Japan's Floating World transports viewers to the popular and enticing entertainment districts established in Edo (present- day Tokyo) in the mid-1600s. Through more than 50 artworks from the acclaimed John C. Weber Collection, visitors can encounter the alluring realm known as the “floating world,” notably its famed pleasure quarter, the Yoshiwara. Masterpieces of painting, luxurious Japanese robes, woodblock-printed guides and decorative arts tell the story of how the art made to represent Edo’s seductive courtesans, flashy Kabuki actors and extravagant customs gratified fantasies and fueled desires. At a time when a strict social hierarchy regulated most aspects of the samurai and townsmen’s lives, the floating world provided a temporary escape. The term “floating world,” or ukiyo, originated from a common Buddhist phrase referring to the suffering of the physical world, which was inverted to signify a realm of boundless indulgence. Both a state of mind and a set of locales, the floating world refers to the diversions available in the brothel districts and Kabuki theaters of Edo, a city whose population had reached a million by the beginning of the 18th century. The floating world’s rise to prominence gave birth to an outpouring of new artistic production, in the form of paintings and woodblock prints that advertised celebrities and spread knowledge of the city’s famous theaters and brothels. -

For Use Only the Library

FOR USE ONLY I THE LIBRARY preliminary catalogue of the Japanese prints and othe illustrations in the Library of the School of Oriental & African Studies By s. Matsudaira The Library 1972 {_ '("' ( '2. -.3r - ,., ,. ... - ,.,. \ r-.1' ')\ SI c -,:-,..:_1) /' J J L INDEX OF JAPliliESE PRINTS & OTHER ITEMS KEY 1. Artist's name 2. Size (in centinetres) and shape of print 3. Description 4. Title (series and individual) 5. Publisher 6. Censor seal, kiwame seal, year-date seal 7. Signature 8. Date 9. References, etc. ( .... /{,_ 8/ y --7 I ') - (1 4t '1. ANONYMOUS '1 - '1 '1 • (Anonymous) 2. Oban. 23.6 x 35.8 3. At the gate of a red-light district ( it might be Shinagawa), two maidservants guiding a customer; another two are waiting for the arrival of their customer. 4. None 5. None 6. None 7. None 8. ea ,'1820 9. '1 - 2 - 3 1. Anonymous) 2. Oban. 37.0 x 25.2. 2ptych. (A set from, a series?) 3. Singing instructor's room. People learning short songs - "Dodoitsu". 4. Title: TOsei misuji no tanoshimi (Enjoyment a la mode with a three-stringed instrument). 5. None 6. None 7. None 8. ea 1850 9. 1 - 4 1. (Anonymous) 2. Oban. 38.0 x 25.8 3. Minamoto Yoshiie, in 1063, releasing 1000 cranes with golden tags tied to their legs at the top of Mt. Kamakura so that the Genji family might prosper for a long time. 4. None 5. Nishimura Yohachi 6. Kiwame seal 7. None 8. ea '1840 9. 1 - 5 1. (Anonymous) 2. -

Japanische Kunst

Inhalt Japanische Kunst .............................................................................................................................. 2 Japanische Holzschnitte ................................................................................................................... 9 Shunga / Erotika ............................................................................................................................. 30 Chinesische Kunst ........................................................................................................................... 33 Südasien und Südostasien .............................................................................................................. 60 Afrika .............................................................................................................................................. 66 Südamerika ..................................................................................................................................... 69 Russische Kunst .............................................................................................................................. 70 Europäische Kunst .......................................................................................................................... 72 Europäisches Kunstgewerbe .......................................................................................................... 77 Signens Kunstauktionen • Julie Weißenberg-Déville • Riehler Str. 77 • 50668 Köln 2 Bücher / Books .............................................................................................................................. -

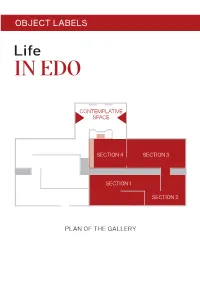

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Oda Nobunaga in Japanese Videogames the Case of Nobunaga’S Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013)

Trabajo Fin de Máster Oda Nobunaga en los videojuegos japoneses El caso de Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Oda Nobunaga in Japanese videogames The case of Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Autora Claudia Bonillo Fernández Directoras Elena Barlés Báguena Amparo Martínez Herranz Facultad de Filosofía y Letras/ Departamento de Historia del Arte Curso 2017-2018 2 ÍNDICE I. PRESENTACIÓN DEL TRABAJO .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Delimitación del tema y causas de su elección ..................................................................................................... 3 2. Estado de la cuestión ............................................................................................................................................. 5 3. Objetivos del trabajo ............................................................................................................................................. 9 4. Metodología .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 4.1. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material bibliográfico ........................................................... 10 4.2. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material documental ............................................................. 11 4.3. Trabajo de campo ........................................................................................................................................ -

Ukiyo-E: Pictures of the Floating World

Ukiyo-e: pictures of the Floating World The V&A's collection of ukiyo- e is one of the largest and finest in the world, with over 25,000 prints, paintings, drawings and books. Ukiyo-e means 'Pictures of the Floating World'. Images of everyday Japan, mass- produced for popular consumption in the Edo period (1615-1868), they represent one of the highpoints of Japanese cultural achievement. Popular themes include famous beauties and well-known actors, renowned landscapes, heroic tales and folk stories. Oniwakamaru subduing the Giant Carp (detail), Totoya Hokkei, In the Edo period (1615- about 1830-1832. Museum no. E.3826:1&2-1916 1868), fans provided a popular format for print designers' ingenuity and imagination. The designs produced for fans are usually themed around summer, festivals, and the lighter side of life. Ukiyo-e prints from the collection are available for study in the V&A Prints and Drawings study room. What are ukiyo-e? The art of ukiyo-e is most frequently associated with colour woodblock prints, popular in Japan from their development in 1765 until the closing decades of the Meiji period Source URL: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/u/ukiyo-e-pictures-of-the-floating-world/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth305/#3.4.2 © Victoria and Albert Museum Saylor.org Used by permission. Page 1 of 8 (1868-1912). The earliest prints were simple black and white prints taken from a single block. Sometimes these prints were coloured by hand, but this process was expensive. In the 1740s, additional woodblocks were used to print the colours pink and green, but it wasn't until 1765 that the technique of using multiple colour woodblocks was perfected. -

Capturing the Body Ryūkōsai’S Notes on “Realism” in Representing Actors on Stage

Capturing the Body Ryūkōsai’s Notes on “Realism” in Representing Actors on Stage Akiko Yano Ryūkōsai Jokei 流光斎如圭 is known as the late eighteenth- century Osaka artist who created “realistic” kabuki actor likenesses (nigao 似顔; kaonise 顔似せ) for the first time outside of Edo.1 His dates are not known, but according to the dating of his works, he was active between 1776 and 1809. His excellent skills in creating actor portraits were famous among his contemporaries, and he was once described as “capturing their true essence” by one of the most enthusiastic Osaka kabuki fans and connoisseurs of the time.2 Japanese scholarship on Ryūkōsai began from the end of the 1920s with the work of Kuroda Genji 黒田源次 and Haruyama Takematsu 春 山武松.3 After a brief burst of research and publication, however, there were decades of silence until the study of Ryūkōsai was taken up again in the late 1960s. Matsudaira Susumu 松平進 was the most prominent scholar in the field, and the leading scholars today include Roger Keyes and Kitagawa Hiroko 北川博子. The special exhibition at the British Museum in 2005, “Kabuki Heroes on the Osaka Stage: 1780-1830,” was a recent significant step forward for the study of Osaka kabuki theater and actor prints after the earlier exhibitions in Philadelphia in 1973 by Keyes and in Japan in 1975 by Matsudaira.4 Ryūkōsai zuroku 流光斎図録 (2009), co-authored and edited by Andrew Gerstle and myself, cata- logues all possible Ryūkōsai prints and paintings known at the time of its publication.5 Ryūkōsai zuroku lists a total of 46 prints and 15 paintings located in Japan, Europe, and the United States.6 The subjects of Ryūkōsai’s prints and paintings are mainly kabuki actors from Osaka. -

Minneapolis Institute of Art to Present Retrospective of Yoshitoshi, Japan’S Last Great Master of Woodblock Prints

PRESS RELEASE Minneapolis Institute of Art to Present Retrospective of Yoshitoshi, Japan’s Last Great Master of Woodblock Prints 2400 Third Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55404 artsmia.org Moon: Actor Ichikawa Sanshō as Kezori Kuemon, from the series The Snow, Moon, and Flowers (Setsugekka no uchi), 1890, Published by Akiyama Buemon, Carved by Wada Yūjirō, Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper, The Mary Griggs Burke Endowment Fund established by the Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, gifts of various donors, by exchange, and gift of Edmond Freis in memory of his parents, Rose and Leon Freis 2017.106.239 MINNEAPOLIS—January 7, 2020—A new exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) celebrates the work of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892), considered the last major artist of the traditional Japanese woodblock print, known as ukiyo-e. “Yoshitoshi: Master Draftsman Transformed” highlights the artist’s process, his technical and innovative skills as a draftsman, and how he responded to Japan’s changing cultural tastes between 1860 and 1890. The 43 artworks on display—ranging from sketches, drawings, paintings, and many printed masterworks—include a selection from Mia’s 2017 acquisition of nearly 300 objects by Yoshitoshi from the Edmond Freis collection. The exhibition is on view February 1 through April 12, 2020, in Mia’s Cargill Gallery. “Yoshitoshi was a formidable draftsman and the exhibition includes works by his own hands that showcase his innovative vision and skills and how his original idea was turned into a woodblock print,” said Andreas Marks, PhD, Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese & Korean Art at Mia. -

Rethinking 'Beauties': Women and Humor in the Late Edo Tōkaidō

Rethinking ‘Beauties’: Women and Humor in the Late Edo Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui Ann Wehmeyer The Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui (1844-1847, 東海道五十三対) is a Japanese ukiyo-e prints series created in collaboration by three of the foremost Japanese print artists of the nineteenth century: Hiroshige (1797-1858), Kuniyoshi (1797- 1861), and Kunisada (1786-1864). The Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui differs from other, mostly earlier, series on the theme of stations along the Tōkaidō Road such as landscapes, or beauties set in landscapes, by taking historical legends and folklore as its predominant subject matter, and combining figures and landscape. A literal rendition of the title of the series is ‘Fifty-three Pairings along the Tōkaidō Road.’1 Timothy Clark suggests that the term tsui 対, ‘pairings,’ might refer to the linking of a legendary event, or some subject associated with the place, to each station of the highway.2 Writ large, this series may be read as a compendium of encounters en route. Many of the figures depicted in the scene for each station are themselves travellers, some famous, others ordinary folk. While the majority of the prints in the series depict male subjects, or illustrate scenes that include both men and women, there are a fair number that depict individual women. In addition to the portrayal of noted women of history, paramours of famous military heroes, supernatural female figures of traditional folklore, and female ghosts, the Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui depicts anonymous women performing daily activities, primarily in transit or at labour. In the case of anonymous women, humour and beauty work in tandem to engage the viewer’s imagination. -

Japanese Prints of the Floating World

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current Honors College 5-8-2020 Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world Madison Dalton James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029 Part of the Acting Commons, Art Education Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Dalton, Madison, "Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world" (2020). Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current. 10. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savoring the Moon: Japanese Prints of the Floating World _______________________ An Honors College Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Visual and Performing Arts James Madison University _______________________ by Madison Britnell Dalton Accepted by the faculty of the Madison Art Collection, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors College. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Virginia Soenksen, Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Director, Madison Art Collection and Lisanby Dean, Honors College Museum Reader: Hu, Yongguang Associate Professor, Department of History Reader: Tanaka, Kimiko Associate Professor, Department of Sociology Reader: , , PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Honors Symposium on April 3, 2020. -

Extrême-Orient 14 12 16 Extrême-Orient Extrême-Orient Paris MER - C RED I 14 D É Cemb Re 2016 VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES PARIS Pierre Bergé & Associés

Extrême-Orient PARIS - MERCREDI 14 DÉcembRE 2016 _14_12_16 EXTRÊME-ORIENT Pierre Bergé & associés Société de Ventes Volontaires_agrément n°2002-128 du 04.04.02 Paris 92 avenue d’Iéna 75116 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Bruxelles Avenue du Général de Gaulle 47 - 1050 Bruxelles T. +32 (0)2 504 80 30 F. +32 (0)2 513 21 65 www.pba-auctions.com VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES PARIS Pierre Bergé & associés EXTRÊME-ORIENT DATE DE LA VENTE / DATE OF THE AUCTION Mercredi 14 décembre 2016 à 13 heures 30 Wednesday, december 14th 2016 at 1:30 pm LIEU DE VENTE / LOCATION Drouot-Richelieu - Salles 5 et 6 9, rue Drouot 75009 Paris EXPOSITIONS PUBLQUES / PUBlic VieWinG Mardi 13 décembre de 11 heures à 18 heures Mercredi 14 décembre de 11 heures à 12 heures Tuesday, december 13th from 11:00 am to 6:00 pm Wednesday, december 14th from 11:00 am to 12:00 pm TÉLÉPHONE PENDANT L’EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE ET LA VENTE T. +33 (0)1 48 00 20 05 CONTACTS POUR LA VENTE Daphné Vicaire T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 [email protected] Harold Lombard T. + 32 (0)2 504 80 [email protected] EXPERT POUR LA VENTE Alice Jossaume, Cabinet Portier 26 boulevard Poissonnière 75009 Paris T. + 33 (0)1 48 00 03 41 E. [email protected] CATALOGUE ET RÉSULTATS CONSULTABLES EN LIGNE www.pba-auctions.com 4 Départements ARCHÉOLOGIE PIERRE BeRGÉ Daphné Vicaire Président T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 15 MEUBLES ET OBJETS D’ART [email protected] TABLEAUX-DESSINS ANCIENS ANTOINE GOdeAU ORIENT ET EXTRÊME-ORIENT VINS & SPIRITUEUX Vice-président EXPERTISE-INVENTAIRE Sophie Duvillier Commissaire Priseur habilité Daphné Vicaire T.