Laws Governing Tax & Tax Like Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxpayers Associations in Central European Countries

33183 Taxpayer Associations in Central and Public Disclosure Authorized Eastern Europe Their mission: to increase the rule of law, entrepreneurship, and economic growth Their coverage: 9 countries, 20 national associations with over 300 local branches Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Anna Hansson and Bjorn Tarras Wahlberg, August 2001 2 Taxpayer Associations in Central and Eastern Europe Their mission: to increase the rule of law, entrepreneurship, and economic growth Their coverage: 9 countries, 20 national associations with over 300 local branches What They Do? - increase transparency and accountability in the public sector - promote business and entrepreneurial activity - spread general knowledge about taxes to individuals and enterprises - assist entrepreneurs and individuals to combat irregular tax inspections and provide legal advice - contribute to the democratic process through media and public education - educate adults as well as schoolchildren on taxes and explain the link between taxes and government spending 3 1. Introduction The World Bank and many other international agencies are now assisting developing countries and countries in transition to build capacity in national and local tax administrations. It is generally acknowledged that there is no one-size-fits-all strategy to solve the problem of inefficiencies and weak capacity in a tax administration; however, it is generally accepted that there is a need for a comprehensive approach to deal with the problems. Better management, competitive pay and transparent and non arbitrary rewards processes as well as investment in information technology are important elements of a reform package. At the same time, reform initiatives need to aim at reforming the tax system itself and determine if there are ways for example, to simplify tax rates, broaden the tax base, and eliminate special exemptions among other. -

Improving the Tax System in Indonesia

OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 998 Improving the Tax System Jens Matthias Arnold in Indonesia https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k912j3r2qmr-en Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 30-Oct-2012 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Unclassified ECO/WKP(2012)75 IMPROVING THE TAX SYSTEM IN INDONESIA ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT WORKING PAPERS No. 998 By Jens Arnold All OECD Economics Department Working Papers are available through OECD's Internet website at http://www.oecd.org/eco/Workingpapers English - Or. English JT03329829 Complete document available on OLIS in its original format This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. ECO/WKP(2012)75 ABSTRACT/RESUME Improving the tax system in Indonesia Indonesia has come a long way in improving its tax system over the last decade, both in terms of revenues raised and administrative efficiency. Nonetheless, the tax take is still low, given the need for more spending on infrastructure and social protection. With the exception of the natural resources sector, increasing tax revenues would be best achieved through broadening tax bases and improving tax administration, rather than changes in the tax schedule that seems broadly in line with international practice. Possible measures to broaden the tax base include bringing more of the self-employed into the tax system, subjecting employer-provided fringe benefits and allowances to personal income taxation and reducing the exemptions from value-added taxes. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

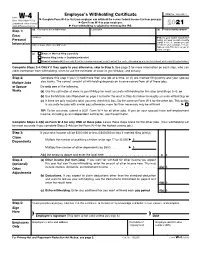

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Financial Transaction Taxes

FINANCIAL MM TRANSACTION TAXES: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers Center for Capital Markets Competitiveness 1 FINANCIAL TRANSACTION TAXES: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers James J. Angel, Ph.D., CFA Associate Professor of Finance Georgetown University [email protected] McDonough School of Business Hariri Building Washington, DC 20057 202-687-3765 Twitter: @GUFinProf The author gratefully acknowledges financial support for this project from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chamber or Georgetown University. 2 Financial Transaction Taxes: A tax on investors, taxpayers, and consumers FINANCIAL TRANSACTIN TAES: Table of Contents A tax on investors, taxpayers, and Executive Summary .........................................................................................4 consumers Introduction .....................................................................................................6 The direct tax burden .......................................................................................7 The indirect tax burden ....................................................................................8 The derivatives market and risk management .............................................. 14 Economic impact of an FTT ............................................................................17 The U.S. experience ..................................................................................... 23 International experience -

International Tax Cooperation and Capital Mobility

CEPAL CEPALREVIEW REVIEW 77 • AUGUST 77 2002 65 International tax cooperation and capital mobility Valpy FitzGerald University of Oxford The international mobility of capital and the geographical edmond.fitzgerald @st-antonys.oxford.ac.uk dispersion of firms have clear advantages for the growth and modernization of Latin America and the Caribbean, but they also pose great challenges. Modern principles of capital taxation for open developing economies indicate the need to find the correct balance between the encouragement of private investment and the financing of social infrastructure, both of which are necessary for sustainable growth. This balance can be sub-optimal when countries compete for foreign investment by granting tax incentives or applying conflicting principles in determining the tax base. The fiscal authorities of the region could obtain a more equitable share of capital tax revenue, without depressing investment and growth, through more effective regional tax rules, double taxation treaties, information sharing and treatment of offshore financial centres along the lines already promoted for OECD members. INTERNATIONAL TAX COOPERATIONAUGUST AND CAPITAL 2002 MOBILITY • VALPY FITZGERALD 66 CEPAL REVIEW 77 • AUGUST 2002 I Introduction Globalization involves increasing freedom of capital for developing as well as developed countries. Latin movement: both for firms from industrialized countries America and the Caribbean have been at the forefront investing in developing countries, and for financial asset of the liberalization -

Publication 509, Tax Calendars

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P509/2021/A/XML/Cycle13/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 13 10:55 - 31-Dec-2020 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 509 Cat. No. 15013X Contents Introduction .................. 2 Department of the Tax Calendars Background Information for Using Treasury the Tax Calendars ........... 2 Internal Revenue General Tax Calendar ............ 3 Service First Quarter ............... 3 For use in Second Quarter ............. 4 2021 Third Quarter ............... 4 Fourth Quarter .............. 5 Employer's Tax Calendar .......... 5 First Quarter ............... 6 Second Quarter ............. 7 Third Quarter ............... 7 Fourth Quarter .............. 8 Excise Tax Calendar ............. 8 First Quarter ............... 8 Second Quarter ............. 9 Third Quarter ............... 9 Fourth Quarter ............. 10 How To Get Tax Help ........... 12 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 509, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub509. What’s New Payment of deferred employer share of so- cial security tax from 2020. If the employer deferred paying the employer share of social security tax in 2020, pay 50% of the employer share of social security tax by January 3, 2022 and the remainder by January 3, 2023. Any payments or deposits you make before January 3, 2022, are first applied against the first 50% of the deferred employer share of social security tax, and then applied against the remainder of your deferred payments. Payment of deferred employee share of so- cial security tax from 2020. -

Profit Taxation in Germany

Profit Taxation in Germany A brief introduction for corporate investors as of April 2013 Profit Taxation in Germany Imprint Publisher: Luther Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH Anna-Schneider-Steig 22, 50678 Cologne, Germany Telephone +49 221 9937 0, Facsimile +49 221 9937 110 [email protected] Editor: Nicole Fröhlich, Telephone +49 69 27229 24830 [email protected] Art Direction: VISCHER&BERNET GmbH Agentur für Marketing und Werbung, Mittelstraße 11 / 1 70180 Stuttgart, Telefon +49 711 23960 0, Telefax +49 711 23960 49, [email protected] Copyright: These texts are protected by copyright. You may make use of the information contained herein with our written consent, if you do so accurately and cite us as the source. Please contact the editors in this regard. Disclaimer Although every effort has been made to offer current and correct information, this publication has been prepared to give general guidance only. It cannot substitute individual legal and/or tax advice. This publication is distributed with the understanding that Luther, the editors and authors cannot be held responsible for the results of any actions taken on the basis of information contained herein or omitted, nor for any errors or omissions in this regard. 2 Contents 6. Loss utilization 6.1. Minimum Taxation 1. Tax rates 6.2. Anti-loss trafficking rules (“change-of-ownership rules”) 1.1. German-based corporations 6.3. No Restructuring Escape 1.2. Partnerships 6.4. Intra-Group Escape 1.3. Branches 6.5. Hidden Reserve-Escape page 4 pages 10 & 11 2. Taxable income 7. Tax neutral reorganisations pages 4 & 5 page 12 3. -

Relationship Between Tax and Price and Global Evidence

Relationship between tax and price and global evidence Introduction Taxes on tobacco products are often a significant component of the prices paid by consumers of these products, adding over and above the production and distribution costs and the profits made by those engaged in tobacco product manufacturing and distribution. The relationship between tax and price is complex. Even though tax increase is meant to raise the price of the product, it may not necessarily be fully passed into price increase due to interference by the industry driven by their profit motive. The industry is able to control the price to certain extent by maneuvering the producer price and also the trade margin through transfer pricing. This presentation is devoted to the structure of taxes on tobacco products, in particular of excise taxes. Outline Tax as a component of retail price Types of taxes—excise tax, import duty, VAT, other taxes Basic structures of tobacco excise taxes Types of tobacco excise systems Tax base under ad valorem excise tax system Comparison of ad valorem and specific excise regimes Uniform and tiered excise tax rates Tax as a component of retail price Domestic product Imported product VAT VAT Import duty Total tax Total tax Excise tax Excise tax Wholesale price Retail Retail price Retail & retail margin Wholesale Producer Producer & retail margin Industry profit Importer's profit price CIF value Cost of production Excise tax, import duty, VAT and other taxes as % of retail price of the most sold cigarettes brand, 2012 Total tax -

What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Spring 2014 What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax? Wendy G. Gerzog University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift ommonC s, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation What's Wrong with a Federal Inheritance Tax?, 49 Real Prop. Tr. & Est. L.J. 163 (2014-2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT'S WRONG WITH A FEDERAL INHERITANCE TAX? Wendy C. Gerzog* Synopsis: Scholars have proposed a federal inheritance tax as an alternative to the current federal transfer taxes, but that proposal is seriously flawed. In any inheritance tax model, scholars should expect to see significantly decreased compliance rates and increased administrative costs because, by focusing on the transferees instead of on the transferor, an inheritance tax would multiply the number oftaxpayers subject to the tax. This Article reviews common characteristics ofexisting inheritance tax systems in the United States and internationally-particularly in Europe. In addition, the Article analyzes the novel Comprehensive Inheritance Tax (CIT) proposal, which combines some elements of existing inheritance tax systems with some features ofthe current transfer tax system and delivers the CIT through the federal income tax system. -

3 Inheritance Taxation

LWS Working Paper Series No. 35 Inheritance Taxation in Comparative Perspective Manuel Schechtl June 2021 Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), asbl Inheritance Taxation in Comparative Perspective Manuel Schechtl* May 25, 2021 Abstract The role of inheritances for wealth inequality has been frequently addressed. However, until recently, comparative data has been scarce. This paper compiles inheritance tax information from EY Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide and combines it with microdata from the Luxembourg Wealth Study. The results indicate substantial differences in the tax base and the distributional potential of inheritance taxation across countries. Keywords: taxes, wealth, inheritance, inheritance tax *Humboldt Universita¨t zu Berlin; Email: [email protected] 1 1 Introduction The relevance of inheritances for the wealth distribution remains a widely debated topic in the social sciences. Using different comparative data sources, previous studies highlighted the positive association between inheritances received and the wealth rank (Fessler and Schu¨rz 2018) or household net worth (Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein 2013). Recent research highlighted the contribution of transferred wealth to overall wealth inequality in this very journal (Nolan et al. 2021). These studies have generated important insights into the importance of inherited wealth beyond national case studies (Black et al. 2020) or economic models of estate taxation (De Nardi and Yang 2016). However, institutional characteristics, such as taxes on inheritances, are seldomly scrutinised. As a notable exemption, Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein examine the association of household net worth and the inheritance tax rate (2013). Due to the lack of detailed comparative data on the design of inheritance taxation, they include inheritance taxes measured as top marginal tax rate in their analysis. -

Broad-Based Low-Rate Property Tax in Lithuania

REAL PROPERTY TAXES AND PROPERTY MARKETS IN CEE COUNTRIES AND CENTRAL ASIA M. Radvan, R. Franzsen, W. J. McCluskey & F. Plimmer Broad-Based Low-Rate Property Tax in Lithuania DOVILĖ MINGĖLAITĖ & LIUCIJA BIRŠKYTĖ1 Abstract It can be argued that the potential of the real property tax as an important source of local government revenue has not been fully exploited in Lithuania. Much has been done to improve the quality of real property assessments. Both buildings and land taxes are ad valorem taxes and the standard for assessment is a true market value. Mass valuation methods are used and the tax base of all property has to be reassessed every five years. The information on the value of property is easily accessible. In the case of discrepancies between the value produced by mass valuation and an individual valuation, the taxpayer has a right to appeal. In order to have a more productive and »equitable« real estate tax, several improvements are possible. The unification of taxation rules for real estate property (buildings and other structures) and land under a single law would produce a more transparent, simpler tax system that would also be easier to understand and administer. At the same time, the tax base could be broadened by eliminating many of the abundant exemptions and other consessions. In addition, policy makers should set the threshold for the taxation of residential real property that would be both socially just and which woud generate revenue at socially acceptable and economically feasible rates. Keywords: • Lithuania • property tax • immovable property tax • valuation • tax reform CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESS: Dovilė Mingėlaitė, Lecturer, Ateities st.