University of Birmingham St. Petersburg And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political and Moral Themes in the Works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1980 Political and moral themes in the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn Isaiah L. Parnell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Parnell, Isaiah L., "Political and moral themes in the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn" (1980). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625102. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-sqe1-6046 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political and Moral Thanes in the Works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts by Isiah L. Parnell APPROVAL SHEET 1 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, August 198Q longham Ki ii To The Gang: Michelle, Shawn, Anita, April, and Corey. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. .... .............................. v ABSTRACT. ......... ......... .............. .......... vi INTRODUCTIONT . 2 CHAPTER I. THE ROLE OF THE ARTIST. ........... 8 THE TRADITIONAL VIEW OF ART AND THE ARTIST............... 9 SOLZHENITSYN'S POLITICAL PURPOSE....... 11 SOLZHENITSYN AS AN HISTORIAN............................ 13 SOLZHENITSYN AS A PROPHET................ 16 LITERATURE AS A MEMORIAL. -

The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Edited by Julian W

Cambridge University Press 052153643X - The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Edited by Julian W. Connolly Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov held the unique distinction of being one of the most impor- tant writers of the twentieth century in two separate languages, Russian and English. Known for his verbal mastery and bold plots, Nabokov fashioned a literary legacy that continues to grow in significance. This volume offers a con- cise and informative introduction to the author’s fascinating creative world. Specially commissioned essays by distinguished scholars illuminate numerous facets of the writer’s legacy, from his early contributions as a poet and short- story writer to his dazzling achievements as one of the most original novelists of the twentieth century. Topics receiving fresh coverage include Nabokov’s narrative strategies, the evolution of his worldview, and his relationship to the literary and cultural currents of his day. The volume also contains valuable supplementary material such as a chronology of the writer’s life and a guide to further critical reading. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 052153643X - The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Edited by Julian W. Connolly Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO NABOKOV EDITED BY JULIAN W. CONNOLLY University of Virginia © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 052153643X - The Cambridge Companion to Nabokov Edited by Julian W. Connolly Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521536431 C Cambridge University Press 2005 This book is in copyright. -

University of Birmingham St. Petersburg and Moscow In

University of Birmingham St. Petersburg and Moscow in twentieth-century Russian literature Palmer, Isobel DOI: 10.1057/978-1-137-54911-2_12 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Palmer, I 2017, St. Petersburg and Moscow in twentieth-century Russian literature. in J Tambling (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Literature and the City. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 197-214. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1- 137-54911-2_12 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 25/10/2018 For Springer Nature terms of reuse for archived author accepted manuscripts (AAMs) of subscription books and chapters see: https://www.palgrave.com/gp/journal-authors/aam-terms-v1 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Proquest Dissertations

British Policy Towards Russian Refugees in the Aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution Elina Hannele Multanen Ph.D. Thesis The School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London University of London ProQuest Number: U120850 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U120850 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis examines British government policy towards Russian refugees in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution and the Civil War in Russia. As a consequence of these two events, approximately one million Russians opposing the Bolshevik rule escaped from Russia. The Russian refugee problem was one of the major political and humanitarian problems of inter-war Europe, affecting both individual countries of refuge, as well as the international community as a whole. The League of Nations had been formed in 1919 in order to promote international peace and security. The huge numbers of refugees from the former Russian Empire, on the other hand, were seen as a threat to the intemational stability. Consequently, the member states of the League for the first time recognised the need for intemational co-operative efforts to assist refugees, and the post of High Commissioner for Russian Refugees was established under the auspices of the League. -

Faithful Ruslan

Review Essay: FAITHFUL RUSLAN Nadja Jernakoff* The date given at the end of the Russian text of Vernyi R uslan is 1963-1965. Its first publication in Russian by Possev-Verlag in Frankfurt, West Germany is dated 1975. Since then readers of German, French, Swedish, Norwegian, Italian, etc. — more than a dozen languages in all — have had the opportunity to read this splendid novella by Georgi Vladimov, a prominent and highly talented Russian writer who lives in the Soviet Union. With the appearance of this translation by Michael Glenny, English-language readers will, at last, be able to sample for themselves the novel which many Russians regard as Vladimov's masterpiece. It is well known that for many years a story initially called simply "The Dogs" circulated within the Soviet Union by way of samizdat. Because of its outstanding literary qualities it was, at one time, attributed to the pen of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Vladimov retitled the book Faithful Ruslan during a long period of meticulous rewriting of his story which, in its final form, was smuggled to the West in 1974. The book deals with the heroic spirit of a German Shepherd dog trained from early puppyhood to guard prisoners in a labor camp. The dog's finest attributes are his devotion to Duty (the word is capitalized in the Russian text) and his loyalty to his master. The story begins at the time when Ivan Denisovich left off, that is, at the time of partial abolition * Nadja Jernakoff is Instructor of Russian at Union College, Schenectady, New York. 1 Faithful Ruslan: The Story of a Guard Dog, by Georgi Vladimov. -

2020 Convention Program.Pdf

aseees Association for Slavic, East European, & Eurasian Studies 2020 ASEEES VIRTUAL CONVENTION Nov. 5-8 • Nov. 14-15 ASSOCIATION FOR SLAVIC, EAST EUROPEAN, & EURASIAN STUDIES 52nd Annual ASEEES Convention November 5-8 and 14-15, 2020 Convention Theme: Anxiety & Rebellion The 2020 ASEEES Annual Convention will examine the social, cultural, and economic sources of the rising anxiety, examine the concept’s strengths and limitations, reconstruct the politics driving anti- cosmopolitan rebellions and counter-rebellions, and provide a deeper understanding of the discourses and forms of artistic expression that reflect, amplify or stoke sentiments and motivate actions of the people involved. Jan Kubik, President; Rutgers, The State U of New Jersey / U College London 2020 ASEEES Board President 3 CONVENTION SPONSORS ASEEES thanks all of our sponsors whose generous contributions and support help to promote the continued growth and visibility of the Association during our Annual Convention and throughout the year. PLATINUM SPONSORS: Cambridge University Press GOLD SPONSOR: East View information Services SILVER SPONSOR: Indiana University, Robert F. Byrnes Russian and East European Institute BRONZE SPONSORS: Baylor University, Modern Languages and Cultures | Communist and Post-Communist Studies by University of California Press | Open Water RUSSIAN SCHOLAR REGISTRATION SPONSOR: The Carnegie Corporation of New York FILM SCREENING SPONSOR: Arizona State University, The Melikian Center: Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies FRIENDS OF ASEEES: -

Resisting Multiple Narratives of Law in Transition Countries: Russia and Beyond

Law & Social Inquiry Volume 40, Issue 2, 531–552, Spring 2015 Resisting Multiple Narratives of Law in Transition Countries: Russia and Beyond Kathryn Hendley BURBANK,JANE. 2004. Russian Peasants Go to Court: Legal Culture in the Countryside, 1905–1917. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Pp. xix 1 374. $49.95 cloth. FEIFER,GEORGE. 1964. Justice in Moscow. New York: Simon and Schuster. Pp. 336. $20.95 paper. KAMINSKAYA,DINA.1982.Final Judgment: My Life as a Soviet Defense Attorney. Trans. Michael Glenny. New York: Simon and Schuster. Pp. 364. Out of print. LEDENEVA,ALENA V. 2013. Can Russia Modernise? Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xv 1 332. $90.00 cloth; $32.99 paper. MCDONALD,TRACY. 2011. Face to the Village: The Riazan Countryside under Soviet Rule, 1921–1930. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Pp. xvii 1 422. $75.00 cloth. POLITKOVSKAYA,ANNA. 2004. Putin’s Russia: Life in a Failing Democracy. Trans. Arch Tait. London: Harvill Press. Pp. 304. $17.00 paper. POPOVA,MARIA. 2012. Politicized Justice in Emerging Democracies: A Study of Courts in Russia and Ukraine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xii 1 197. $103.00 cloth; $29.99 paper. ROMANOVA,OL’GA. 2010. Butyrka. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Astrel’. Pp. 316. 240 rubles. The literature on the role of law in countries with so-called hybrid regimes that are stuck somewhere between democracy and authoritarianism tends to dwell on the politicization of law and the courts. This has the effect of discounting the importance of the vast majority of cases that are decided in accord with the law. -

A Country Doctor's Notebook Mikhail Bulgakov

PRAISE FOR A COUNTRY DOCTOR’S NOTEBOOK “This book has a freshness and liveliness … an epic quality because of the background of Russia’s vastness, the great distances, the weight of the ignorance, the need.” —DORIS LESSING “These straightforward yet extraordinary sketches gain their strength from also being the account of a young man’s growth. One begins to see that he became a novelist not because he had material but because he was storing up passion and temperament.” —V.S. PRITCHETT, NEW STATESMAN “Stories as keen and bright as a scalpel … Courage shines from every angle of this profoundly human collection by the greatest of modern Russian writers.” —SUNDAY TIMES “Bulgakov casts a wonderfully wry, self-deprecating humour. His compassion for human folly is unfailing … These stories stand testament both to human resilience and a remarkable literary talent.” —THE INDEPENDENT A COUNTRY DOCTOR’S NOTEBOOK MIKHAIL BULGAKOV (1891–1940) was born in Kiev, one of seven children born to a university lecturer and a teacher. Although he showed an early interest in theater and literature, he went on to study medicine at Kiev University, and in the early part of the First World War served as a doctor on the front lines. Twice wounded, he left the service and after recovering—and getting over his subsequent morphine addiction—was appointed provincial physician to Smolensk province in 1916. He detailed this experience in A Country Doctor’s Notebook, but the book went unpublished until years after his death. During the Russian Civil War he served briey as a physician for the Ukrainian People’s Army, while most of his family emigrated to France and Germany. -

Heart of a Dog

“I ona byla chelovekom” (For the Dog was Once a Human Being): The Moral Obligation in Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog Andrea McDowell From on Top of the Doghouse As both tsarist and Soviet leadership carried out agendas of silencing and oppression, writers often turned to animals, particularly dogs, to explore the power of voice and the freedom to communicate. In the nineteenth century, Ivan Turgenev’s “Mumu” (1852) describes the impotence and suffering of a mute peasant and his dog, both unable to express themselves and therefore unable to influence their own destinies. Their shared voicelessness represents the serf population’s silent suffering, an injustice Turgenev assails throughout his fiction. Later, in the twentieth century, Georgii Vladimov portrays the horrors of Soviet GULags through the cynomorphic perspective of a prison guard dog in Faithful Ruslan (Vernyi Ruslan 1975). Many writers under Stalin shared not only the helplessness and victimization of non-human animals, but also their voicelessness: some battled endlessly with censors over the right to express themselves freely, while others abandoned their craft for fear of imprisonment and even execution. This code of silence extended far beyond the creative arena, as words and language became dangerous for all citizens, expected to converse in forms of sanctioned discourse only. Mikhail Bulgakov’s novella Heart of a Dog (Sobache serdce 1925) predated Stalin’s reign of power yet proved alarmingly Otherness: Essays and Studies Volume 5 · Number 2 · September 2016 © The Author 2016. All rights reserved. Otherness: Essays and Studies 5.2 prescient with regard to the silencing techniques that characterized Stalinist Russia and the debasing influence of this enforced muteness. -

Intellectuals, the Soviet Regime, and the Gulag: the Construction and Deconstruction of an Ideal

INTELLECTUALS, THE SOVIET REGIME, AND THE GULAG: THE CONSTRUCTION AND DECONSTRUCTION OF AN IDEAL By LISA L. BOOTH A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 By Lisa L. Booth TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................1 2 LABOR CAMPS IN THE PERIOD OF 1929-1933: DEPICTIONS AND POLITICAL USES............................................................11 3 KHRUSHCHEV’S THAW: LABOR CAMPS AND DE-STALINIZATION..............................................................................37 4 PERESTROIKA: LABOR CAMPS AND THE EMERGENCE OF A PUBLIC DISCOURSE....................................................57 5 SOVIET LABOR CAMPS: HISTORIOGRAPHY AND CONTESTED MEANINGS......................................................................71 REFERENCE LIST.........................................................................................................79 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH...........................................................................................85 iii Abstract of Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts INTELLECTUALS, THE SOVIET REGIME, AND THE GULAG: THE -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections withsmall overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300North Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 DRAMATIC AND THEATRICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF GLASNOST IN SOVIET RUSSIA DURING THE FIRST HALF OF THE GORBACHEV EPOCH, 1985-1988 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey Pace Stephens, B.A., M.A. -

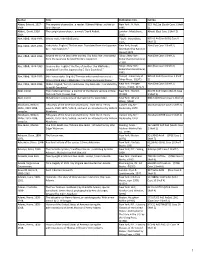

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel.