INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16/10/2017 LIBRARY Rds 701-800 1 Call Number RD-701 KHEIFITS

16/10/2017 LIBRARY RDs 701-800 1 Call number RD-701 KHEIFITS, Iosif Edinstvennaia [The Only One] Lenfil´m, Pervoe tvorcheskoe ob´´edinenie, 1975; released 17 March 1976 Screenplay: Pavel Nilin, Iosif Kheifits, from Nilin’s story ‘Dur´’ Photography: Genrikh Marandzhian Production design: Vladimir Svetozarov Music: Nadezhda Simonian Song written by: Vladimir Vysotskii Nikolai Kasatkin Valerii Zolotukhin Taniusha Fesheva Elena Proklova Natasha Liudmila Gladunko Boris Il´ich Vladimir Vysotskii Maniunia Larisa Malevannaia Iura Zhurchenko Viacheslav Nevinnyi Anna Prokof´evna, Nikolai’s mother Liubov´ Sokolova Grigorii Tatarintsev Vladimir Zamanskii Judge Valentina Vladimirova Ivan Gavrilovich Nikolai Dupak Scientist Aleksandr Dem´ianenko Train passenger Svetlana Zhgun Tachkin Mikhail Kokshenov Train passenger Efim Lobanov Wedding guest Petr Lobanov Black marketer Liubov´ Malinovskaia Anna Vil´gel´movna Tat´iana Pel´ttser Member of druzhina Boris Pavlov-Sil´vanskii Tania’s friend Liudmila Staritsyna Serega Gelii Sysoev Lekha Aleksandr Susnin Head Chef of the Uiut restaurant Arkadii Trusov 90 minutes In Russian Source: RTR Planeta, 13 March 2015 System: Pal 16/10/2017 LIBRARY RDs 701-800 2 Call number RD-702 SAKHAROV, Aleksei Chelovek na svoem meste [A Man in His Place] Mosfil´m, Tvorcheskoe ob´´edinenie Iunost´, 1972; released 28 May 1973 Screenplay: Valentin Chernykh Photography: Mikhail Suslov Production design: Boris Blank Music: Iurii Levitin Song lyrics: M. Grigor´ev Semen Bobrov, Chairman of the Bol´shie bobry kolkhoz Vladimir Men´shov -

Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation

POST-SOVIET POLITICAL PARTY DEVELOPMENT IN RUSSIA: OBSTACLES TO DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION Evguenia Lenkevitch Bachelor of Arts (Honours), SFU 2005 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Political Science O Evguenia Lenkevitch 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Evguenia Lenkevitch Degree: Master of Arts, Department of Political Science Title of Thesis: Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lynda Erickson, Professor Department of Political Science Dr. Lenard Cohen, Professor Senior Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. Alexander Moens, Professor Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. llya Vinkovetsky, Assistant Professor External Examiner Department of History Date DefendedlApproved: August loth,2007 The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the 'Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

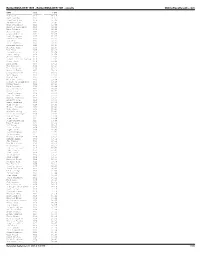

Bolderboulder 10K Results

BolderBOULDER 1986 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Jon Luff M18 31:14 Jeff Sanchez M20 31:23 Jonathan Hume M18 31:58 Ed Ostrovich M27 32:04 Mark Stromberg M21 32:09 Michael Velasquez M16 32:21 Rick Renfrom M32 32:22 James Ysebaert M22 32:24 Louis Anderson M32 32:25 Joel Thompson M27 32:27 Kevin Collins M31 32:34 Rob Welo M22 32:42 Bill Lawrance M31 32:44 Richard Bishop M28 32:45 Chester Carl M33 32:47 Bob Fink M29 32:51 David Couture M18 32:54 Brent Terry M24 32:58 Chris Nelson M16 33:02 Robert III Hillgrove M18 33:05 Steve Smith M16 33:08 Rick Katz M37 33:11 Tom Donohoue M30 33:14 Dale Garland M28 33:17 Michael Tobin M22 33:18 Craig Marshall M28 33:20 Mark Weeks M34 33:21 Sam Wolfe M27 33:23 William Levine M25 33:26 Robert Jr Dominguez M30 33:26 David Teague M32 33:28 Alex Accetta M16 33:29 Dave Dreikosen M32 33:31 Peter Boes M22 33:32 Daniel Bieser M24 33:32 Matt Strand M18 33:33 George Frushour M23 33:34 Everett Bear M16 33:35 Bruce Pulford M31 33:36 Jeff Stein M26 33:40 Thomas Teschner M22 33:42 Mike Chase M28 33:43 Michael Junig M21 33:43 Parrick Carrigan M26 33:44 Jay Kirksey M30 33:46 Todd Moore M22 33:49 Jerry Duckworth M24 33:49 Rick Reimer M37 33:50 RaY Keogh M28 33:50 Dave Dooley M39 33:50 Roger Innes M26 33:50 David Chipman M22 33:51 Brian Boehm M17 33:51 Michael Dunlap M29 33:51 Arthur Mizzi M30 33:52 Jim Tanner M18 33:52 Bob Hillgrove M41 33:52 Ramon Duran M18 33:52 Ken Jr. -

Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cimpean, Oana Carmina, "Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2283. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOUIS ARAGON AND PIERRE DRIEU LA ROCHELLE: SERVILITYAND SUBVERSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Oana Carmina Cîmpean B.A., University of Bucharest, 2000 M.A., University of Alabama, 2002 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 August, 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Professor Alexandre Leupin. Over the past six years, Dr. Leupin has always been there offering me either professional advice or helping me through personal matters. Above all, I want to thank him for constantly expecting more from me. Professor Ellis Sandoz has been the best Dean‘s Representative that any graduate student might wish for. I want to thank him for introducing me to Eric Voegelin‘s work and for all his valuable suggestions. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

French Historical Studies Style Sheet

The French Historical Studies Style Guide comprises three parts: (1) a style sheet listing elements of style and format particular to the journal; (2) starting on page 6 of this guide, the Duke University Press Journals Style Guide, which offers general rules for DUP journals based on The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. (CMS); and (3) starting on page 12, an explanation with examples of the journal’s format for citations and reference list or bibliography. French Historical Studies Style Sheet ABBREVIATIONS In citations and in reference lists the names of the months are given as follows: Jan., Feb., Mar., Apr., May, June, July, Aug., Sept., Oct., Nov., Dec. ABSTRACTS For every article (but not for review articles or contributions to a forum), an abstract must be provided in both English and French, with both an English and a French title. Neither version of the abstract should exceed 150 words. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments, headed “Acknowledgments,” appear at the end of the article’s text and are written in the third person. The author thanks the anonymous reviewers of French Historical Studies, whose suggestions were inspirational and invaluable. EPIGRAPHS An epigraph, which may appear at the start of an article or a section, has an attribution that includes the author’s name or the author’s name and the work’s title. No other bibliographical information is required, and the source is not included in the references list unless it is cited elsewhere in the text. No footnote should be attached to an epigraph. I propose that the figurations of women to be found within Rousseau’s texts are constitutive of the organization of public and domestic life in the post-revolutionary world of bourgeois propriety. -

Current Issues of the Russian Language Teaching XIV

Current issues of the Russian language teaching XIV Simona Koryčánková, Anastasija Sokolova (eds.) Current issues of the Russian language teaching XIV Simona Koryčánková, Anastasija Sokolova (eds.) Masaryk University Press Brno 2020 Sborník prací pedagogické fakulty mu č. 276 řada jazyková a literární č. 56 Edited by: doc. PhDr. Mgr. Simona Koryčánková, Ph.D., Mgr. Anastasija Sokolova, Ph.D. Reviewed by: Elena Podshivalova (Udmurt State University), Irina Votyakova (University of Granada) © 2020 Masaryk University ISBN 978-80-210-9781-0 https://doi.org/10.5817/CZ.MUNI.P210-9781-2020 BYBY NC NDND CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Crea�ve Commons A�ribu�on-NonCommercial-NoDeriva�ves 4.0 CONTENTS METHODOLOGY ISSUES ............................................................................ 5 A Reading-Book in Russian Literature: The Text Preparation and the First Opinion of its Use ............................................................. 6 Josef Dohnal Poetic Text Of Vasily Shukshin – The Red Guelder Rose In Russian As A Foreign Language Class ....................................................................................................13 Marianna Figedyová Language Games in Teaching Russian as a Foreign Language ................................................21 Olga Iermachkova Katarína Chválová Specificity of Language Material Selection for Introduction of Russian Imperative Mood in “Russian as a Foreign Language” Classes ........................................................................... 30 Elena Kolosova Poetic Texts in Teaching of