Oran Milo Roberts, Texas's Forgotten Fire-Eater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 17 Issue 2 Article 5 10-1979 Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson Ralph W. Steen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Steen, Ralph W. (1979) "Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol17/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIAnON 3 GOVERNOR MIRIAM A. FERGUSON by Ralph W. Steen January 20, 1925 was a beautiful day in Austin, Texas, and thousands of people converged on the city to pay tribute to the first woman to serve the state as governor. Long before time for the inaugural ceremony to begin every space in the gallery of the House of Representatives was taken and thousands who could not gain admission blocked hanways and stood outside the capitol. After brief opening ceremonies, Chief Justice C.M. Cureton administered the oath of office to Lieutenant Governor Barry Miller and then to Governor Miriam A. Ferguson. Pat M. Neff, the retiring governor, introduced Mrs. Ferguson to the audience and she delivered a brief inaugural address. The governor called for heart in government, proclaimed political equality for women, and asked for the good will and the prayers of the women of Texas. -

Nobel Endeavors in Immunology Introducing Dr

SPRING 2012 A PUBLICATION OF SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL FOUNDATION Nobel Endeavors in Immunology Introducing Dr. Bruce Beutler, UT Southwestern’s fifth Nobel Laureate, and the new Center for the Genetics of Host Defense Southwestern Medical Foundation Board of Trustees 2011-2012 Edward M. Ackerman Joe M. Haggar, III Richard R. Pollock Sara Melnick Albert Nancy S. Halbreich Caren H. Prothro The Heritage Society Rafael M. Anchia LaQuita C. Hall Carolyn Perot Rathjen OF SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL FOUNDATION Table of Contents Charlotte Jones Anderson Paul W. Harris* Mike Rawlings table of contents Barry G. Andrews Linda W. Hart Jean W. Roach Joyce T. Alban Mr. and Mrs. Thomas E. McCullough Marilyn H. Augur Joe V. (Jody) Hawn, Jr. Linda Robuck Mr. and Mrs. James R. Alexander Christopher F. McGratty Robert D. Rogers Ralph W. Babb, Jr. Jess T. Hay Anonymous (11) Carmen Crews McCracken McMillan Editor Doris L. Bass Frederick B. Hegi, Jr. Catherine M. Rose George A. Atnip# Ferd C. and Carole W. Meyer Nobel Endeavors in Immunology Peter Beck Jeffrey M. Heller* Billy Rosenthal Marilyn Augur* William R. and Anne E. Montgomery Heidi Harris Cannella The threads of Dr. Bruce Beutler’s scientific 3 # Jill C. Bee Julie K. Hersh Lizzie Horchow Routman* Paul M. Bass* Kay Y. Moran career are inextricably woven into the fabric of W. Robert Beavers, M.D. Barbara and Robert Munford Gil J. Besing Thomas O. Hicks Robert B. Rowling* Creative Director UT Southwestern’s history. From intern to mid-career Drs. Paul R. and Robert H. Munger# Jan Hart Black Sally S. Hoglund Stephen H. -

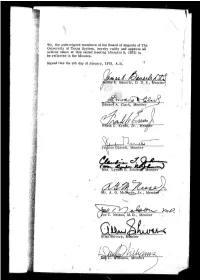

Board Minutes for January 9, 1973

1 ~6 ]. J We, the uudersigaed members of the Board of Regeats of The Uaiversity of Texas System, hereby ratify aad approve all z actions takea at this called meetiag (Jauuary 9, 1973) to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 9Lh day of Jaauary, -1973, A.D. ol Je~ins Garrett, Member c • D., Member Allan( 'Shivers, M~mber ! ' /" ~ ° / ~r L ,.J J ,© Called Meeting Meeting No. 710 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages I and 2 O January ~, 1973 '~ Austin, Texas J~ 1511 ' 1-09-7) ~ETING NO. 710 TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1973.--Pursuant to the call of the Chair on January 6, 1973 (and which call appears in the Minutes of the meeting of that date), the Board of Regents convened in a Called Session at i:00 p.m~ on January 9, 1973, in the Library of the Joe C. Thompson Conference Center, The Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, with the follow- ing in attendance: ,t ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Regent James E. Baue-~ None Regent Edward Clark Regent Frank C. Erwin, Jr. "#~?::{ill Regent Jenkins Garrett Regent (Mrs.) Lyndon Johnson Regent A. G. McNeese, Jr. );a)~ Regent Joe T. Nelson Regent Allan Shivers Regent Dan C. Williams Secretary Thedford Chancellor LeMaistre Chancellor Emeritus Ransom Deputy Chancellor Walker (On January 5, 1973, Governor Preston Smith f~amed ~the < following members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System: ,~ ¢.Q .n., k~f The Honorable James E. Bauerle, a dentist of San Antonio, to succeed the Honorable John Peace of San Antonio, whose term had expired. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

2020-2022 Law School Catalog

The University of at Austin Law School Catalog 2020-2022 Table of Contents Examinations ..................................................................................... 11 Grades and Minimum Performance Standards ............................... 11 Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Registration on the Pass/Fail Basis ......................................... 11 Board of Regents ................................................................................ 2 Minimum Performance Standards ............................................ 11 Officers of the Administration ............................................................ 2 Honors ............................................................................................... 12 General Information ................................................................................... 3 Graduation ......................................................................................... 12 Mission of the School of Law ............................................................ 3 Degrees ..................................................................................................... 14 Statement on Equal Educational Opportunity ................................... 3 Doctor of Jurisprudence ................................................................... 14 Facilities .............................................................................................. 3 Curriculum ................................................................................. -

The Texian Sept

Calendar of Events 2015 Quarterly Meetings THE TEXIAN Sept. 11-12, 2015 La Quinta Inn & Suites Belton, 229 West Loop 121, The Official Publication of The Sons of the Republic of Texas Belton, TX 76513; (866) 527-1498, Room Rate $101 + tax, cut off date August 21, 2015; Please identify yourself as SRT. VOL VIII NUMBER 3 AUGUST 2015 Hampton Inn & Suites, 7006 Navarro, Victoria, TX 77904; Dec. 4-5, 2015 ND (361) 573-9911, Room Rate $99 + tax, 1 King or 2 Queen NEWS RELEASE FOR THE 202 ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF MEDINA cut off date November 18, 2015; Please identify yourself as AUGUST 15, 2015 SRT. The public is invited to attend our 15th annual ceremony commemorating the Battle of Medina, this being the 202nd anniversary of the bloodiest battle in Texas history! The Battle of Medina occurred on August 18, 1813 2015 SRT Events between the Royal Spanish Army and the Republican Army of the North when between 800 and 1,300 Ameri- March 2 Texas Independence Day March 6 Fall of the Alamo cans, Tejanos, Indians, and Spanish soldiers died in this all but forgotten battle which historians have named March 27 Goliad Massacre the Gutierrez-Magee Expedition. Since August 18th is on Tuesday this year, we will hold our normal com- April 21 San Jacinto Day memorative ceremony beginning at 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, August 15, 2015 under the large Oak trees on Old September 19 Texian Navy Day on the Battleship Texas Applewhite Road. We will have a Color Guard representing the U.S.A., Spain, Texas and Mexico, plus descen- October 2 Battle of Gonzales dants of the men who fought and died in this battle. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865

“VICTORY IS OUR ONLY ROAD TO PEACE”: TEXAS, WARTIME MORALE, AND CONFEDERATE NATIONALISM, 1860-1865 Andrew F. Lang, B. A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Richard G. Lowe, Major Professor Randolph B. Campbell, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lang, Andrew F. “Victory is Our Only Road to Peace”: Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865. Master of Arts (History), May 2008, 148 pp., bibliography, 106 titles. This thesis explores the impact of home front and battlefield morale on Texas’s civilian and military population during the Civil War. It addresses the creation, maintenance, and eventual surrender of Confederate nationalism and identity among Texans from five different counties: Colorado, Dallas, Galveston, Harrison, and Travis. The war divided Texans into three distinct groups: civilians on the home front, soldiers serving in theaters outside of the state, and soldiers serving within Texas’s borders. Different environments, experiences, and morale affected the manner in which civilians and soldiers identified with the Confederate war effort. This study relies on contemporary letters, diaries, newspaper reports, and government records to evaluate how morale influenced national dedication and loyalty to the Confederacy among various segments of Texas’s population. Copyright 2008 by Andrew F. Lang ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Richard Lowe, Randolph B. Campbell, and Richard B. McCaslin for their constant encouragement, assistance, and patience through every stage of this project. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Unit 7-Civil War and Reconstruction

Unit 7-Civil War and Reconstruction 1861-1876 Unit 7 Vocabulary • Sectionalism – Concern for regional needs and interests. • Secede – To withdraw, including the withdrawal of states from the Union. • Blockade – Blocking off an area to keep supplies from getting in or out. • Emancipation – The act of giving someone freedom • Reconstruction – The act of rebuilding; Generally refers to the rebuilding of the Union following the Civil War. • Martial Law – The imposition of laws by a military authority, general in defeated territories. • Sharecropper – A tenant farmer who receives a portion of the crop. • Popular Sovereignty – Independent power given to the people. • The Democrats were the dominant political party, and had Political very little competition from the Parties Whig party. -Texans would vote for southern democrats until the 1980’s! • Sam Houston, though he never joined the party, supported the Know-Nothing party which opposed immigration to the United States. Know-Nothing party flag Republican Party • 1854 Northerners created the Republican Party to stop the expansion of slavery. Southerners saw the Republican party as a threat and talk of secession increased. (The act of a state withdrawing from the Union) Abolitionist movement • Beginning in the 1750s, there was a widespread movement after the American Revolution that believed slavery was a social evil and should eventually be abolished. • After 1830, a religious movement led by William Lloyd Garrison declared slavery to be a personal sin and demanded the owners repent immediately and start the process of emancipation. (Granting Freedom to slaves) An Abolitionist is someone who wanted to abolish slavery William Lloyd Garrison Slavery in the South • In 1793 with the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney, the south saw an explosive growth in the cotton industry and this greatly increased demand for slave labor in the South. -

Unit 8 Test—Wed. Feb. 25

Unit 8 Study Guide: Pre-AP 2015 Civil War and Reconstruction Era (Ch. 15 & 16) Expectations of the Student/Essential Questions Identify the Civil War and Reconstruction Era of Texas History and define its characteristics Explain the significance of 1861 Explain reasons for the involvement of Texas in the Civil War such as states’ rights, slavery, secession, and tariffs Analyze the political, economic, and social effects of the Civil War and Reconstruction in Texas Identify significant individuals and events concerning Texas and the Civil War such as John Bell Hood, John Reagan, Francis Lubbock, Thomas Green, John Magruder and the Battle of Galveston, the Battle of Sabine Pass, and the Battle of Palmito Ranch Identify different points of view of political parties and interest groups on important Texas issues Essential Topics of Significance Essential People (5) Causes of Civil War Food shortages/ John Wilkes Booth Robert E. Lee substitutes Union vs. Conf. advantages Jefferson Davis Abraham Lincoln Appomattox Courthouse TX Secession Convention Dick Dowling Francis Lubbock State government collapse Fort Sumter “Juneteenth” John S. Ford John Magruder Battle of Galveston Freedmen’s Bureau Ulysses S. Grant Pendleton Murrah Battle of Sabine Pass (3) Recons. Plans Battle of Brownsville Thomas Green Elisha M. Pease (3) Recons. Amendments Red River Campaign Andrew Jackson Hamilton John Reagan (5) Provisions of Texas Battle of Palmito Ranch John Bell Hood Lawrence Sullivan Ross Constitution of 1869 Texans help for war effort Ironclad Oath Andrew Johnson Philip Sheridan Women’s roles Immigration/Emigration Albert Sidney Johnston James W. Throckmorton Essential Vocabulary Dates to Remember states’ rights preventive strike amendment Unit 8 Test—Wed. -

Civil War in the Lone Star State

page 1 Dear Texas History Lover, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. It has a mystique that no other state and few foreign countries have ever equaled. Texas also has the distinction of being the only state in America that was an independent country for almost 10 years, free and separate, recognized as a sovereign gov- ernment by the United States, France and England. The pride and confidence of Texans started in those years, and the “Lone Star” emblem, a symbol of those feelings, was developed through the adventures and sacrifices of those that came before us. The Handbook of Texas Online is a digital project of the Texas State Historical Association. The online handbook offers a full-text searchable version of the complete text of the original two printed volumes (1952), the six-volume printed set (1996), and approximately 400 articles not included in the print editions due to space limitations. The Handbook of Texas Online officially launched on February 15, 1999, and currently includes nearly 27,000 en- tries that are free and accessible to everyone. The development of an encyclopedia, whether digital or print, is an inherently collaborative process. The Texas State Historical Association is deeply grateful to the contributors, Handbook of Texas Online staff, and Digital Projects staff whose dedication led to the launch of the Handbook of Civil War Texas in April 2011. As the sesquicentennial of the war draws to a close, the Texas State Historical Association is offering a special e- book to highlight the role of Texans in the Union and Confederate war efforts.