Cpostgraduate Journal of Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

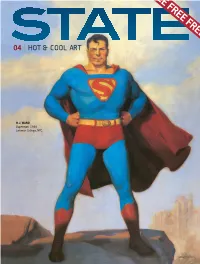

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

Artist and Institution: a Painful Encounter

Fernanda Albuquerque Doris Salcedo Artist and institution: a painful encounter Quote: ALBUQUERQUE. Fernanda; SALCEDO, Doris. Artist and institution: a This interview was held at the artist’s Bogotá studio in painful encounter. Porto Arte: Revista de Artes Visuais. Porto Alegre: PPGAV- November 2013. It is part of the PhD thesis Artistic practices UFRGS, v. 22, n. 37, p.163-166, jul.-dez. 2017. ISSN 0103-7269 | e-ISSN 2179- 8001. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22456/2179-8001.80123 oriented to context and criticism in the institutional sphere, developed at the PPGAV-UFRGS with Prof. Mônica Zielinsky as its advisor. ² Translated by Roberto Cataldo Costa Abstract: This interview is about the work process of Colombian Fernanda Albuquerque: artist Doris Salcedo regarding her work Shibboleth, developed How was the research process around Turbine Hall and Tate for Turbine Hall, at London’s Tate Modern (2007) as part of the Modern for proposing Shibboleth? Unilever Series. Keywords: Artist. Contemporary art. Context. Institution. Criti- Doris Salcedo: cism. Doris Salcedo. I get the impression that for the Western world, Tate is like Shibboleth is Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s 2007 work the cultural heart of Europe. It is really a place that managed made for Turbine Hall – the grand entrance hall of London’s to become a public space in the deepest sense of the term. Tate Modern.¹ The work features a huge crack in the museum’s There people think and reflect on highly important aspects of gigantic lobby. A slit, a crack, a rupture, a cut, a fault. It is part of life. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

Britain After Empire

Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Britain After Empire This page intentionally left blank Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Professor of Political Sociology, University of Birmingham, UK © P. W. Preston 2014 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2014 978-1-137-02382-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

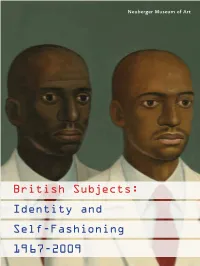

British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Neuberger Museum of Art British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 For full functionality please open using Acrobat 8. 4 Curator’s Foreword To view the complete caption for an illustration please roll your mouse over the figure or plate number. 5 Director’s Preface Louise Yelin 6 Visualizing British Subjects Mary Kelly 29 An Interview with Amelia Jones Susan Bright 37 The British Self: Photography and Self-Representation 49 List of Plates 80 Exhibition Checklist Copyright Neuberger Museum of Art 2009 Neuberger Museum of Art All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers. Director’s Foreword Curator’s Preface British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 is the result of a novel collaboration British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 began several years ago as a study of across traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries at Purchase College. The exhibition contemporary British autobiography. As a scholar of British and postcolonial literature, curator, Louise Yelin, is Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Professor of Literature. I intended to explore the ways that the life writing of Britons—construing “Briton” and Her recent work addresses the ways that life writing and self-portraiture register subjective “British” very broadly—has registered changes in Britain since the Second World War. responses to changes in Britain since the Second World War. She brought extraordinary critical Influenced by recent work that expands the boundaries of what is considered under the insight and boundless energy to this project, and I thank her on behalf of a staff and audience rubric of autobiography and by interdisciplinary exchanges made possible by my institutional that have been enlightened and inspired. -

Branding of the Museum

The Branding of the Museum Julian Stallabrass [‘Brand Strategy of Art Museum’, in Wang Chunchen, ed., University and Art Museum, Tongji University Press, Shanghai 2011, published in Chinese. Also published in Cornelia Klinger, ed., Blindheit und Hellsichtigkeit: Künstlerkritik an Politik und Gesellschaft der Gegenwart, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 303-16; and in a revised and updated version as ‘The Branding of the Museum’, Art History, vol. 37, no. 1, February 2014, pp. 148-65.] The British Museum shop, 2008. Photo: JS While museums have long had names, identities and even logos, their explicit branding by specialist companies devoted to such tasks is relatively new.1 The brand is an attempt to 1 This piece has had a long gestation, and has benefitted from the comments of many participants at lectures and symposia. As a talk, it was first given at the CIMAM 2006 Annual Conference, Contemporary Institutions: Between Public and Private, held at Tate Modern. In the large literature about museums and their changing roles, there has slowly begun to emerge some consideration of branding. Margot A. Wallace, Museum Branding: How to Create and Maintain Image, Loyalty and Support, AltaMira Press, Oxford 2006 is, as its title suggests, a how-to guide. James B. Twitchell, Branded Nation: The Marketing of Megachurch, College Inc. and Museumworld, Simon & Schuster, New York 2004 is a jocular lament about the pervasiveness of marketing culture, which sees the museum, too simply, as providing ‘edutainment’ with no meaningful differentiation from consumer culture. More seriously, Andrew Dewdney/ David Bibosa/ Victoria Walsh, Post-Critical Museology: Theory and Practice in Stallabrass, Branding, p. -

4. Contemporary Art in London

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 미술경영학석사학위논문 Practice of Commissioning Contemporary Art by Tate and Artangel in London 런던의 테이트와 아트앤젤을 통한 현대미술 커미셔닝 활동에 대한 연구 2014 년 2 월 서울대학교 대학원 미술경영 학과 박 희 진 Abstract The practice of commissioning contemporary art has become much more diverse and complex than traditional patronage system. In the past, the major commissioners were the Church, State, and wealthy individuals. Today, a variety of entities act as commissioners, including art museums, private or public art organizations, foundations, corporations, commercial galleries, and private individuals. These groups have increasingly formed partnerships with each other, collaborating on raising funds for realizing a diverse range of new works. The term, commissioning, also includes this transformation of the nature of the commissioning models, encompassing the process of commissioning within the term. Among many commissioning models, this research focuses on examining the commissioning practiced by Tate and Artangel in London, in an aim to discover the reason behind London's reputation today as one of the major cities of contemporary art throughout the world. -

Carlier | Gebauer Press Release Mark Wallinger

carlier | gebauer Press release Mark Wallinger | Mark Wallinger 30.04.- 28.05.2016 Opening: Friday, April 29th, 2016 For his seventh solo exhibition with carlier | gebauer, the Turner Prize winning artist Mark Wallinger will present his new series id Paintings. According to Freud, the id, driven by the pleasure principle, is the source of all psychic energy. Wallinger’s id Paintings (2015) are intuitive and guided by instinct, echoing the primal, impulsive and libidinal characteris - tics of the id. These monumental paintings have grown out of Wallinger’s longstanding self- portrait series, and reference the artist’s own body. Wallinger’s height – or arm span – is the basis of the canvas size, they are exactly this mea - surement in width and double in height. Created by sweeping paint-laden hands across the canvas in active, freeform gestures, the id Paintings bear the evidence of their making and of the artist’s performed encounter with the surface. The perceptible handprints within the paint recall cave paint - ings and signpost a single active participant. The paintings are apprehended at the point of arrest, encouraging forensic examination. Wallinger uses symmetrical bodily gestures, causing the two halves of the canvas to mirror one another. Through this process, reference could be made to the bilateral symmetry of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’, an ideal representation of the human body and its denotations of proportion in mirror writing. The paintings bear a deliberate visual resemblance to the Rorschach test: in recognizing figures and shapes in the material, the viewer reveals their own desires and predilections, or perhaps tries to interpret those of the artist. -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 10

Issue 10 The magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 10 Cover Image: There will be no miracles here, installation view at Mount Stuart. Nathan Coley Photo:Kenneth Hunter >BRIEFING Hot 50 We√come Design Week magazine has put the GSA into its HOT 50 honours list of people and Welcome to Issue 10 of Flow. organisations that have made a significant contribution Nathan Coley’s work, pictured on the front of this issue of Flow, makes a bold declaration – There to design. will be no miracles here. However, the word miracle is derived from the Latin word miraculum The magazine describes the GSA as a leader in the meaning ‘something wonderful’ and had we commissioned Nathan to produce a similar piece of field of design education and work for the School, he could have boldly declared There are miracles here – there is ‘something commends the School for wonderful’ here. engaging in ‘socially relevant design rather that just creating We try to share the ‘something wonderful’ that is The Glasgow School of Art in every issue of Flow a product’. and this issue is no different, sharing with you the successes and achievements of our students, SIE Success for Red Button alumni and staff, but also some of the challenges that the School is facing and the creative ways For the fourth year in succession, in which we are addressing them. This issue looks at scholarships and the co-curriculum.Through GSA students have won prizes our responses to these challenges, we are not only building on our tradition of access, but are in the Scottish Institute continuing to produce graduates who are professionally orientated and socially engaged. -

ANTONY GORMLEY Biography 1950 Born in London, England Lives In

ANTONY GORMLEY Biography 1950 Born in London, England Lives in London, England SELECTED AWARDS 2014 Knighthood for Services to the Arts 2013 Praemium Imperiale Prize in Sculpture 2012 Obayashi Prize 2007 Bernhard Heiliger Award for Sculpture 2004 Honorary Doctorate, Newcastle University 2003 Honorary Doctorate, Cambridge University Honorary Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge Royal Academician 2001 Honorary Doctorate, Open University Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects 2000 British Design and Art Direction Silver Award for Illustration Civic Trust Award for The Angel of the North Fellow, Royal Society of Arts 1999 South Bank Art Award for Visual Art 1998 Honorary Doctorate, University of Sunderland Honorary Doctorate, University of Central England, Birmingham Honorary Fellowship, Goldsmith's College, University of London 1997 Order of the British Empire 1994 Turner Prize, Tate Gallery, London, England SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 GROUND, Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, The Netherlands 2021 ANTONY GORMLEY, National Gallery Singapore, Singapore FIELD FOR THE BRITISH ISLES, Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art (NGCA) at the National Glass Centre, Sunderland, United Kingdom LEARNING TO BE, Schauwerk Sindelfingen, Germany PRESENT, Rana Kunstforening, Mo Rana, Norway Last updated: 19 July 2021 2020 IN HABIT, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Marais, Paris 2019 Antony Gormley, Royal Academy of Arts, London, United Kingdom BREATHING ROOM: ART BASEL UNLIMITED, Art Basel, Switzerland -

Channel 4'S 25 Year Anniversary

Channel 4’s 25 year Anniversary CHANNEL 4 AUTUMN HIGHLIGHTS Programmes surrounding Channel 4’s anniversary on 2nd November 2007 include: BRITZ (October) A two-part thriller written and directed by Peter Kosminsky, this powerful and provocative drama is set in post 7/7 Britain, and features two young and British-born Muslim siblings, played by Riz Ahmed (The Road to Guantanamo) and Manjinder Virk (Bradford Riots), who find the new terror laws have set their altered lives on a collision course. LOST FOR WORDS (October) Channel 4 presents a season of films addressing the unacceptable illiteracy rates among children in the UK. At the heart of the season is a series following one dynamic headmistress on a mission to wipe out illiteracy in her primary school. A special edition of Dispatches (Why Our Children Can’t Read) will focus on the effectiveness of the various methods currently employed to teach children to read, as well as exploring the wider societal impact of poor literacy rates. Daytime hosts Richard and Judy will aim to get children reading with an hour-long peak time special, Richard & Judy’s Best Kids’ Books Ever. BRITAIN’S DEADLIEST ADDICTIONS (October) Britain’s Deadliest Addictions follows three addicts round the clock as they try to kick their habits at a leading detox clinic. Presented by Krishnan Guru-Murphy and addiction psychologist, Dr John Marsden, the series will highlight the realities of addiction to a variety of drugs, as well as alcohol, with treatment under the supervision of addiction experts. COMEDY SHOWCASE (October) Channel 4 is celebrating 25 years of original British comedy with six brand new 30-minute specials starring some of the UK’s best established and up and coming comedic talent.