An Interview with Mark Wallinger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoration of the Right to Protest at Parliament

Law, Crime and History (2013) 1 LETTING DOWN THE DRAWBRIDGE: RESTORATION OF THE RIGHT TO PROTEST AT PARLIAMENT Kiron Reid1 Abstract This article analyses the history of the prohibition of protests around Parliament under the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. This prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless permission had been obtained in writing from the police in advance. This measure both formed part of a pattern of the then Labour Government to restrict protest and increase police powers, and was symbolically important in restricting protest that was directed at politicians at a time when politicians have been very unpopular. The Government of Tony Blair had been embarrassed by a one-man protest by peace campaigner, Brian Haw. In response to sustained defiance, Mr. Blair’s successor as Labour Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, and opposition Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs pledged to remove the restrictions, but this was not acted on by Parliament until September 2011. This article argues that the original restrictions were unnecessary, and that the much narrower successor provisions could be improved by being drafted more specifically. Keywords: protest, demonstration, protest at Parliament, freedom of speech, Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005, Brian Haw. Introduction This is about the sorry tale of sections 132-138 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (SOCPA).2 These prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless advance written permission had been obtained from the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis. -

CAN ART HISTORY DIGEST NET ART? Julian Stallabrass from Its

165 CAN ART HISTORY DIGEST NET ART? Julian Stallabrass From its beginnings, Internet art has had an uneven and confl icted relation- ship with the established art world. There was a point, at the height of the dot-com boom, when it came close to being the “next big thing,” and was certainly seen as a way to reach new audiences (while conveniently creaming off sponsorship funds from the cash-rich computer companies). When the boom became a crash, many art institutions forgot about online art, or at least scaled back and ghettoized their programs, and that forgetting became deeper and more widespread with the precipitate rise of con- temporary art prices, as the gilded object once more stepped to the forefront of art-world attention. Perhaps, too, the neglect was furthered by much Internet art’s association with radical politics and the methods of tactical media, and by the extraordinary growth of popular cultural participation online, which threatened to bury any identifi ably art-like activity in a glut of appropriation, pastiche, and more or less knowing trivia. One way to try to grasp the complicated relation between the two realms is to look at the deep incompatibilities of art history and Internet art. Art history—above all, in the paradox of an art history of the contemporary— is still one of the necessary conduits through which works must pass as they move through the market and into the security of the museum. In examining this relation, at fi rst sight, it is the antagonisms that stand out. Lacking a medium, eschewing beauty, confi ned to the screen of the spreadsheet and the word processor, and apparently adhering to a discred- ited avant-gardism, Internet art was easy to dismiss. -

Sessional Orders and Resolutions

House of Commons Procedure Committee Sessional Orders and Resolutions Third Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 November 2003 HC 855 Published on 19 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Depleted Uranium P 4 We Talk a Lot About the Loyalty of These Daisaku Ikeda P 5 2 Pm Animals, and Their Willingness to Serve Gyosei Handa P 5 Us

ABOLISHABOLISH WARWAR Newsletter No: 9 Autumn 2007 Price per Issue £1 Remembrance Day - What will you be doing? Whether you wear red poppies, white poppies or both, whether you take part in a Remembrance service or The MAW AGM not, or you organise an event to question the fact of war, the day we Saturday 10th November remember those who have died in 11 am - 3 pm war is the day when MAW’s message should be loud and clear - war must Wesley’s Chapel 49 City Road end if we are not to add yet more London EC1Y 1AU names to our memorials. (nearest tube station Old Street) Animals in War Among the innocents we should Speaker: Craig Murray remember in November are the Craig is well known as the UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan who highlighted the human rights abuses he found there, millions of animals that took part in embarrassing the proponents of the ‘War on Terror’ with the and died for our political failures. result he is no longer in the Diplomatic Corps. He is a In 2004 a new monument appeared in fascinating, informative and funny speaker, with a wealth of London - the Animals in War experience to draw on. “Craig Murray has been a deep Memorial, inspired by Jilly Cooper’s embarrassment to the entire Foreign Office.” Jack Straw book of the same name. It ‘honours The AGM is open to all and is free. If you can get to the millions of conscripted animals London, then get to the AGM. And bring your friends. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

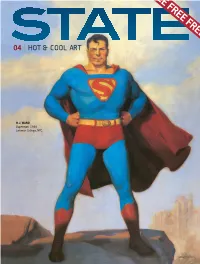

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

WES HILL Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with No Alternative

Wes Hill, Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative WES HILL Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative ABSTRACT What is a hipster, and why has this cultural trope become so resonant of a particular mode of artistic and connoisseurial expression in recent times? Evolving from its beatnik origins, the stereotypical hipster today is likely to be a globally aware “creative” who nonetheless fails in their endeavour to be an exemplar of progressive cultural taste in an era when cultural value is heavily politicised. Today, artist memes and hipster memes are almost interchangeable, associated with people who are desperate to be fashionably distinctive, culturally literate or as having discovered some obscure cultural phenomenon before anyone else. But how did we arrive at this situation where elitist and generically “arty” connotations are perceived in so many cultural forms? This article will attempt to provide an historical context to the rise of the contemporary, post-1990s, hipster, who emerged out of the creative and entrepreneurial ideologies of the digital age – a time when artistic creations lose their alternative credence in the markets of the creative industries. Towards the end of the article “hipster hate” will be examined in relation to post- critical practice, in which the critical, exclusive, and in-the-know stances of cultural connoisseurs are thought to be in conflict with pluralist ideology. Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative Although the hipster trope is immediately recognisable, it has been allied with a remarkable diversity of styles, objects and activities over the last two decades, warranting definition more in terms of the attempt to promote counter-mainstream sensibilities than pertaining to a specific aesthetic as such. -

Michael Landy Selected Biography Born in London, 1963 Lives And

Michael Landy Selected Biography Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK 1985-88, Goldsmith's College Solo Exhibitions 2015 Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam Three-piece, Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York 2004 Welcome To My World built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, London, UK 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian Wearing), Approach Gallery, London, UK 1999 Michael Landy at Home, 7 Fashion Street, London, UK 1996 The Making of Scrapheap Services, Waddington Galleries, London, UK Scrapheap Services, Chisenhale Gallery, London; Electric Press Building, Leeds, UK (organised by the HenryMoore -

Gallery Ambassador Job Description

Gallery Ambassador Fixed Term Contracts & Casual Contracts Job description ……. Background For over a century the Whitechapel Gallery has premiered world-class artists from modern masters such as Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Frida Kahlo to contemporaries such as Sophie Calle, Lucian Freud, Gilbert & George and Mark Wallinger. With beautiful galleries, exhibitions, artist commissions, collection displays, historic archives, education resources, inspiring art courses, dining room and bookshop, the expanded Gallery is open all year round, so there is always something free to see. The Gallery is a touchstone for contemporary art internationally, plays a central role in London’s cultural landscape and is pivotal to the continued growth of the world’s most vibrant contemporary art quarter. Role With this role, you will act as a front of house Ambassador for Whitechapel Gallery and provide an excellent experience to all the visitors. The role requires Ambassadors to provide up to date information on all our Exhibition and Education Programme and to support the Gallery’s charitable aims, by promoting our ticketed Exhibitions, Public Event Programme, and Membership scheme and encourage donations. Invigilate the gallery spaces and any off-site exhibition spaces. Meeting the gallery’s needs to staff events such as season openings, patron tours etc. Working hours will vary and Gallery Ambassador may be offered work on any day of the week including Saturdays, Sundays, evenings and bank holidays. The services provided to the Gallery are on a fixed term contract basis for an hourly rate. Accountability The Gallery Ambassadors report to the Visitor Services Manager. Visitor Experience Providing excellent visitor care following existing guidelines and policies. -

Mark Wallinger Italian Lessons

Victoria Miro Mark Wallinger Italian Lessons Private View 5:30 – 7:30pm, Saturday 27 January 2018 Exhibition 27 January – 10 March 2018 Victoria Miro Venice, Il Capricorno, San Marco 1994, 30124 Venice, Italy Image: Mark Wallinger, Genius of Venice (detail), 1991 Glass, catalogue pages, nightlights, metal brackets 38 x 32 x 6 cm / 15 x 12 5/8 x 2 3/8 inches each, 7 parts Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Todd-White Art Photography © Mark Wallinger Victoria Miro, in collaboration with Hauser & Wirth, is delighted to present Italian Lessons, an exhibition by Mark Wallinger. Selected by the artist especially for Victoria Miro Venice, the works on display date from 1991 to 2016 and reflect a career-long engagement with ideas of power, authority, artifice and illusion. While sources of inspiration include the Italian masters and masterpieces in Italian collections, this is the first time many of these works have been shown in Italy. “In a sense, the exhibition is like my mini Grand Tour.” – Mark Wallinger Encompassing autobiography and art history, the Italian Lessons of the exhibition title are manifold. They refer to Wallinger’s own education and to his exposure to the Italian masters: via a charismatic college lecturer in his native Essex; a seminal exhibition in London; a bicycle tour from Paris to Florence. Equally, the Lessons make reference to the cornerstones of art history – such as the development of perspective and trompe-l’oeil techniques – and the shifts in consciousness they have brought about. Lessons theological as well as pedagogical may be deduced in the content or context of his source material, part of a long-term consideration of religion as one of the ideological forces through which order is imposed on the world. -

You Cannot Be Serious: the Conceptual Innovator As Trickster

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5791 Chapter 8: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster The Accusation The artist does not say today, “Come and see faultless work,” but “Come and see sincere work.” Edouard Manet, 18671 When Edouard Manet exhibited Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, the critic Louis Etienne described the painting as an “unbecoming rebus,” and denounced it as “a young man’s practical joke, a shameful open sore not worth exhibiting this way.”2 Two years later, when Manet’s Olympia was shown at the Salon, the critic Félix Jahyer wrote that the painting was indecent, and declared that “I cannot take this painter’s intentions seriously.” The critic Ernest Fillonneau claimed this reaction was a common one, for “an epidemic of crazy laughter prevails... in front of the canvases by Manet.” Another critic, Jules Clarétie, described Manet’s two paintings at the Salon as “challenges hurled at the public, mockeries or parodies, how can one tell?”3 In his review of the Salon, the critic Théophile Gautier concluded his condemnation of Manet’s paintings by remarking that “Here there is nothing, we are sorry to say, but the desire to attract attention at any price.”4 The most decisive rejection of these charges against Manet was made in a series of articles published in 1866-67 by the young critic and writer Emile Zola. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Sensational Cities, John J.