Artists' Moving Image in Britain Since 1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

Sarah Lucas: SITUATION Absolute Beach Manrubble

Teachers’ Notes Whitechapel Gallery Autumn 2013 Sarah Lucas: SITUATION Absolute Beach Man Rubble. Also including Annette Krauss: Hidden Curriculum/In Search of the Missing Lessons; Contemporary Art Society: Nothing Beautiful Unless Useful; and Supporting Artists: Acmes First Decade 1972 -1982. whitechapelgallery.org , 1996, c-print, 152.5 x 122 cm, copyright the artist, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. HQ, Sadie Coles courtesy the artist, copyright 152.5 x 122 cm, c-print, 1996, , Self-Portrait with Skull Self-Portrait Sarah Lucas Sarah Introduction: Teachers’ Notes This resource has been put together by the Whitechapel Gallery’s Education Department to introduce teachers to each season of exhibitions and new commissions at the Gallery. It explores key themes within the main exhibition to support self-directed visits. We encourage schools to visit the gallery Tuesday – Thursday during term time, and to make use of our Education Studios for free. Autumn 2013 at the Whitechapel Gallery Sarah Lucas: SITUATION Absolute Beach Man Rubble Throughout the lower and upper floors of the Gallery are two decades of works by British artist, Sarah Lucas. The bawdy euphemisms, repressed truths, erotic delights and sculptural possibilities of the sexual body lie at the heart of Sarah Lucas’s work. First coming to prominence in the 1990s, this British artist’s sculpture, photography and installation have established her as one of the most important figures of her generation. This exhibition takes us from Lucas’s 1990s’ foray into the salacious perversities of British tabloid journalism to the London premiere of her sinuous, light reflecting bronzes: limbs, breasts and phalli intertwine to transform the abject into a dazzling celebration of polymorphous sexuality. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Film and Media As a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 14 (2017) 157–173 DOI: 10.1515/ausfm-2017-0007 Film and Media as a Site for Memory in Contemporary Art Domingo Martinez Rosario Universidad Nebrija (Madrid, Spain) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This article explores the relationship between film, contemporary art and cultural memory. It aims to set out an overview of the use of film and media in artworks dealing with memory, history and the past. In recent decades, film and media projections have become some of the most common mediums employed in art installations, multi-screen artworks, sculptures, multi-media art, as well as many other forms of contemporary art. In order to examine the links between film, contemporary art and memory, I will firstly take a brief look at cultural memory and, secondly, I will set out an overview of some pieces of art that utilize film and video to elucidate historical and mnemonic accounts. Thirdly, I will consider the specific features and challenges of film and media that make them an effective repository in art to represent memory. I will consider the work of artists like Tacita Dean, Krzysztof Wodiczko and Jane and Louise Wilson, whose art is heavily influenced and inspired by concepts of memory, history, nostalgia and melancholy. These artists provide examples of the use of film in art, and they have established contemporary art as a site for memory. Keywords: contemporary art, cultural memory, memory, film, temporality. Introduction Film and video have become two of the most common disciplines of contemporary art in recent decades. -

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO Until 10.30 on 22.1.20

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 22 January UNDER EMBARGO until 10.30 on 22.1.20 Artists launch Art Fund campaign to save Prospect Cottage, Derek Jarman’s home & garden, for the nation – Art Fund launches £3.5 million public appeal to save famous filmmaker’s home – National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund and Linbury Trust give major grants in support of innovative partnership with Tate and Creative Folkestone – Leading artists Tilda Swinton, Tacita Dean, Jeremy Deller, Michael Craig-Martin, Isaac Julien, Howard Sooley, and Wolfgang Tillmans give everyone the chance to own art in return for donations through crowdfunding initiative www.artfund.org/prospect Derek Jarman at Prospect Cottage. Photo: © Howard Sooley Today, Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar announced the launch of Art Fund’s £3.5 million public appeal to save and preserve Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, the home and garden of visionary filmmaker, artist and activist, Derek Jarman, for the nation. Twitter Facebook artfund.org @artfund theartfund National Art Collections Fund. A charity registered in England and Wales 209174, Scotland SC038331 Art Fund needs to raise £3.5m by 31 March 2020 to purchase Prospect Cottage and to establish a permanently funded programme to conserve and maintain the building, its contents and its garden for the future. Major grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund, the Linbury Trust, and private donations have already taken the campaign half way towards its target. Art Fund is now calling on the public to make donations of all sizes to raise the funds still needed. Through an innovative partnership between Art Fund, Creative Folkestone and Tate, the success of this campaign will enable continued free public access to the cottage’s internationally celebrated garden, the launch of artist residencies, and guided public visits within the cottage itself. -

PDF Download

CITY OF LONDON’S PUBLIC ART PROGRAMME SCULPTURE IN THE CITY – 2016 EDITION ANNOUNCED 6th Edition to site 15 works in and around architectural landmarks from the Gherkin to the Cheesegrater Large-scale pieces to include works by Sarah Lucas, William Kentridge & Gerhard Marx, Sir Anthony Caro, Enrico David, Jaume Plensa and Giuseppe Penone Jaume Plensa, Laura, 2013, Cast Iron, 702.9 x 86.4 x 261 cm, Photo: Kenneth Tamaka 28 June 2016 – May 2017, June media previews and installation opportunities to be announced www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/sculptureinthecity @sculpturecity /visitthecity @visitthecity #sculptureinthecity 16 May, 2016, London: The City of London’s annual public art programme, Sculpture in the City, places contemporary art works in unexpected locations, providing a visual juxtaposition to the capital’s insurance district. This year’s edition, the largest to date, will showcase 15 works ranging considerably in scale. A seven-metre high, cast-iron head, by Catalan sculptor Jaume Plensa will peer over visitors to the Gherkin, while a series of delicate and playful lead paper chain sculptures © Brunswick Arts | 2016 | Confidential | 1 by Peruvian artist, Lizi Sánchez, will invite the attention of the more observant passer-by in multiple locations including Leadenhall Market, Bishopsgate and in and around the Cheesegrater. The critically acclaimed, open-air exhibition, has built a rapport with many who live, work and visit the area. Sculpture in the City is known for bringing together both established international artists and rising stars. During the month of June, works will begin to appear around the unique architectural mix of London’s City district. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

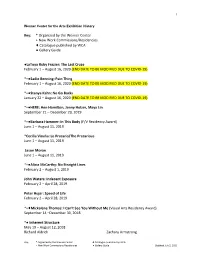

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Thecollective

WORKPLACEGATESHEAD The Old Post Office 19-21 West Street Gateshead, NE8 1AD thecollective Preview: Friday 5th May 6pm – 8pm Exhibition continues: 6th May – 3rd June Opening hours: Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm Issued Wednesday 26th April 2018 Workplace Gateshead is delighted to present the first public exhibition of selected works from The Founding Collective. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Started in 2002 in London by a group of art professionals and families interested in living with contemporary art The Collective is a growing network of groups collecting, sharing and enjoying contemporary art in their homes or places of work. The combined collection of The Founding Group now comprises over 60 original and limited edition works by emerging and established artists. Selected by Workplace this exhibition includes works by: Mel Brimfield, Jemima Brown, Fiona Banner, Libia Castro & Olafur Olafsson, Martin Creed, Tom Dale, Michael Dean, Tacita Dean, Peter Doig, Bobby Dowler, Tracey Emin, Erica Eyres, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Ceal Floyer, Matthew Higgs, Gareth Jones, Alex Katz, Scott King, Jochen Klein, Edwin Li, Hilary Lloyd, Paul McCarthy, Paul Noble, Chris Ofili, Peter Pommerer, James Pyman, Frances Richardson, Giorgio Sadotti, Jane Simpson, Wolfgang Tillmans, Piotr Uklanski, Mark Wallinger, Bedwyr Williams, and Elizabeth Wright. Free public event: Friday 5th May, 5pm - 6pm, all welcome Founding members of The Collective will give an informal introduction to the history of the group, how it works, how it expanded and plans for the future. This will be followed by an open discussion chaired by WORKPLACE directors Paul Moss and Miles Thurlow focusing on the importance of collecting contemporary art, how to make a start regardless of budget, and the challenges and opportunities for new collectors in the North of England. -

Gallery Ambassador Job Description

Gallery Ambassador Fixed Term Contracts & Casual Contracts Job description ……. Background For over a century the Whitechapel Gallery has premiered world-class artists from modern masters such as Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Frida Kahlo to contemporaries such as Sophie Calle, Lucian Freud, Gilbert & George and Mark Wallinger. With beautiful galleries, exhibitions, artist commissions, collection displays, historic archives, education resources, inspiring art courses, dining room and bookshop, the expanded Gallery is open all year round, so there is always something free to see. The Gallery is a touchstone for contemporary art internationally, plays a central role in London’s cultural landscape and is pivotal to the continued growth of the world’s most vibrant contemporary art quarter. Role With this role, you will act as a front of house Ambassador for Whitechapel Gallery and provide an excellent experience to all the visitors. The role requires Ambassadors to provide up to date information on all our Exhibition and Education Programme and to support the Gallery’s charitable aims, by promoting our ticketed Exhibitions, Public Event Programme, and Membership scheme and encourage donations. Invigilate the gallery spaces and any off-site exhibition spaces. Meeting the gallery’s needs to staff events such as season openings, patron tours etc. Working hours will vary and Gallery Ambassador may be offered work on any day of the week including Saturdays, Sundays, evenings and bank holidays. The services provided to the Gallery are on a fixed term contract basis for an hourly rate. Accountability The Gallery Ambassadors report to the Visitor Services Manager. Visitor Experience Providing excellent visitor care following existing guidelines and policies. -

Mark Wallinger Italian Lessons

Victoria Miro Mark Wallinger Italian Lessons Private View 5:30 – 7:30pm, Saturday 27 January 2018 Exhibition 27 January – 10 March 2018 Victoria Miro Venice, Il Capricorno, San Marco 1994, 30124 Venice, Italy Image: Mark Wallinger, Genius of Venice (detail), 1991 Glass, catalogue pages, nightlights, metal brackets 38 x 32 x 6 cm / 15 x 12 5/8 x 2 3/8 inches each, 7 parts Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Todd-White Art Photography © Mark Wallinger Victoria Miro, in collaboration with Hauser & Wirth, is delighted to present Italian Lessons, an exhibition by Mark Wallinger. Selected by the artist especially for Victoria Miro Venice, the works on display date from 1991 to 2016 and reflect a career-long engagement with ideas of power, authority, artifice and illusion. While sources of inspiration include the Italian masters and masterpieces in Italian collections, this is the first time many of these works have been shown in Italy. “In a sense, the exhibition is like my mini Grand Tour.” – Mark Wallinger Encompassing autobiography and art history, the Italian Lessons of the exhibition title are manifold. They refer to Wallinger’s own education and to his exposure to the Italian masters: via a charismatic college lecturer in his native Essex; a seminal exhibition in London; a bicycle tour from Paris to Florence. Equally, the Lessons make reference to the cornerstones of art history – such as the development of perspective and trompe-l’oeil techniques – and the shifts in consciousness they have brought about. Lessons theological as well as pedagogical may be deduced in the content or context of his source material, part of a long-term consideration of religion as one of the ideological forces through which order is imposed on the world.