Roads and Conflict in High Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research on the Relationship Between Transportation Industry and Economic Growth

E3S Web of Conferences 257, 03055 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125703055 AESEE 2021 Research on the Relationship between Transportation Industry and Economic Growth Jiaxin Wu1,a*, Yi Peng2,b, Xubing Zhou3,c 1School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China 2School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China 3School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China Abstract—Transportation industry is the leading capital of social and economic development, which plays an important role in regional economic development. Based on the data of Tibet Autonomous Region in the past 15 years, this paper makes further grey relation analysis and elastic analysis on the basis of analyzing the current situation of its transportation industry and economic development, obtains the conclusion about the development relationship between them. The empirical results show that there is a close relationship between the transportation industry and economic growth in Tibet Autonomous Region, and the development of them is in a state of coordination on the whole. Among them, the promotion effect of freight transport on the economic growth of Tibet is greater than that of passenger transport, and the belt action of economic growth on railway transport is much greater than that on highway transport. of industrial structure, and significantly improved the 1 Introduction investability of Tibet. The second is quantitative analysis method. Pan (2005) investigated the relationship between As a basic industry to promote economic development, the development of transportation and GDP in Tibet and transportation industry plays an increasingly significant believed that the transportation industry had a great role in promoting regional economic development. -

20 Sep 2017 1412077273ER4

Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Project Location and Accessibility .............................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Project Area ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Vision statement .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.6 Scope of the Project ........................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Preliminary Appreciation of project site w.r.t surroundings and Master Paln 2021 .. 4 2.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Factor Considered for Site Selection in New Sikandrbad ..................................................................... 4 2.3 Regional Setting............................................................................................................................................... -

A Tibetan Perspective on Development and Globalization

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 24 Number 1 Himalaya; The Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Article 13 No. 1 & 2 2004 A Tibetan Perspective on Development and Globalization Tashi Tsering University of British Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Tsering, Tashi. 2004. A Tibetan Perspective on Development and Globalization. HIMALAYA 24(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol24/iss1/13 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TASHI TSERING, UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA A TIBETAN PERSPECTIVE ON DEVELOPMENT AND GLOBALIZATION The Chinese word for Tibet, Xizang, means the “western treasure house.” “…the trends in re- cent decades show that the Chinese government may now be success- ful in what it has always wanted to do—to put Tibet on the escalator to be- coming a profitable resource colony. Consumer goods on a Lhasa sidewalk PHOTO: TASHI TSERING INTRODUCTION ovember 30, 1999 marked a turning point in tribute to the scant literature by providing a Tibetan global history. Tens of thousands of ordinary perspective on this complex and relevant subject. The peopleN took to the streets of Seattle to stop the second purpose of this paper is a simple one: to articulate ” round of the World Trade Organization (WTO) what globalization (and thus development) means to Ministerial Conference. -

Elliot Sperling, Professor, Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University

Demographic Changes on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier in the 15th Century and their Implications Speaker: Elliot Sperling, Professor, Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University Chair: Patricia Uberoi, Chairperson, Institute of Chinese Studies 9 April 2015 Institute of Chinese Studies Delhi Elliot Sperling’s presentation provided a brief background to the social, economic and cultural situation of Tibet in the 15th century, as well as, the demographic changes which took place in Tibet during this period. These include the deterioration of the position of Buddhism in India, consequent decline of pilgrimage and reduction of trade with India. These demographic changes in the 15th century, along with its implications on the economy of Tibet, played an important role in Sino-Tibetan relations in the later centuries. It gave an increased level of importance to the Tibetan economy, especially Kham. The demographic changes that took place in Tibet were reflected in the massive migration of Tibetan population into eastern Tibet, making it the most populous part of the Plateau and the influx of Chinese into the province of Sichuan making it the most populous province of China. While pointing towards the implications of the demographic changes that took place in Tibet during 15th century, the speaker argued that the fact that the majority, albeit a slim majority, of the Tibetan population in China resides outside the territory that constitutes present-day Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), has its roots in the changes that took place in the 15th century. He started his presentation by raising an important question i.e., what Tibet is and what the boundaries of Tibet are. -

Roads Routes and Canal Systems

ROADS AND CANALS OF ANCIENT WORLD. ROADS From the earliest times, one of the strongest indicators of a society's level of development has been its road system-or lack of one. Increasing populations and the advent of towns and cities brought with it the need for communication and commerce between those growing population centers. A road built in Egypt by the Pharaoh Cheops around 2500 BC is believed to be the earliest paved road on record-a construction road 1,000 yards long and 60 feet wide that led to the site of the Great Pyramid. Since it was used only for this one job and was never used for travel, Cheops's road was not truly a road in the same sense that the later trade routes, royal highways, and impressively paved Roman roads were. The various trade routes, of course, developed where goods were transported from their source to a market outlet and were often named after the goods which traveled upon them. For example, the Amber Route traveled from Afghanistan through Persia and Arabia to Egypt, and the Silk Route stretched 8,000 miles from China, across Asia, and then through Spain to the Atlantic Ocean. However, carrying bulky goods with slow animals over rough, unpaved roads was a time consuming and expensive proposition. As a general rule, the price of the goods doubled for every 100 miles they had to travel. Some other ancient roads were established by rulers and their armies. The Old Testament contains references to ancient roads like the King's Highway, dating back to 2000 BC. -

Discussions on Current Social and Political Issues*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository DISCUSSIONS ON CURRENT SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ISSUES* All researchers interested in this subject are encouraged to continue the substantive discussion * Opinions of the authors of articles and commentaries in this column may not reflect the view of the publisher. Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 8 (2012 5) 1200-1217 ~ ~ ~ УДК 009 China’s Grand Strategy, Kashmir and Pakistan: Transformation of Islamabad from a Spoiler State to Frontline State for Beijing Dr. Suneel Kumar* Department of Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu Jammu-180006-Jammu and Kashmir, India 1 Received 4.11.2011, received in revised form 11.11.2011, accepted 16.07.2012 China in collaboration with Pakistan has integrated Kashmir in its grand strategy to contain India. Beijing’s involvement in various mega projects related to construction and development of strategic infrastructure in the Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir (PoK), influx of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the Gilgit-Baltistan region, adoption of visa-related controversial policies and invitation to India’s Kashmiri separatist leader, are being seen in the India’s official and strategic circles, as the encirclement of India by China through Kashmir. During the Cold War era, Beijing had bestowed Pakistan with the status of ‘spoiler state’ in order to weaken the natural predominance of India in the South Asian region. Nevertheless, now, it is being viewed that China has transformed Pakistan into a ‘ frontline state’ to contain the increasing Indian influence at regional and global levels. -

Report on China's Development Policy in Tibet

China’s Development Policy in Tibet A Report Tibet Policy Institute 2017 Contents Preface .......................................................................................i Understanding China’s Economic Development Policies in Tibet: From Mao Zedong to Jiang Zemin Period .................................1 Dolma Tsering Ph.D Candidate , Jawaharlal Nehru University The Riddle of Tibet’s Economy ..................................................20 Dr Tenzin Desal Research Fellow, Tibet Policy Institute Saving Tibetans from Tibet: Poverty Alleviation with Chinese Char- acteristics ...................................................................................26 Gabriel Lafitte China’s Model of Economic Development of Tibet: From Darkness to Light, From Feudal Serfdom to Modernity, Thanks To the Gift of Development ........................................................................38 Gabriel Lafitte Outcomes of China’s Development Strategy in Tibet, As Experi- enced by Tibetans ......................................................................54 Gabriel Lafitte Tibet’s Traditional Economy: Comparative Advantage, Value Add- ing and Linkages .......................................................................61 Gabriel Lafitte 13th Five-Year Plan: China’s New National Parks in Tibet .....................................................................................69 Gabriel Lafitte Economy of Tibet Preface Economists who are reliant on GDP growth figures to read the pulse for the state of the economy, it is easy to be -

World Bank Document

Initial Project Information Document (PID) Report No: AB137 Project Name INDIA -Lucknow-Muzaffarpur National Highway Project Region South Asia Regional Office Public Disclosure Authorized Sector Roads and highways (100%) Theme Infrastructure services for private sector development (P); Public expenditure, financial management and procurement (S) Project P077856 Borrower(s) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Implementing Agency(ies) NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA Address: NHAI, Plot No. G5&G6, Sector 10, Dwarka, New Delhi Contact Person: G. R. Singhal, Chief General Manager (East-West Corridor) Tel: 91-11-2507-4100 Fax: 91-11-2508-0360 Email: [email protected] Environment Category A (Full Assessment) Date PID Prepared June 24, 2003 Auth Appr/Negs Date April 15, 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized Bank Approval Date September 30, 2004 1. Country and Sector Background Road transport plays a significant role in India's economy, carrying 80% of the land transport demand. The national highway network has a total length of 58,100 km, which accounts for about 1.8% of the total road network but carries over 40% of the road traffic. With steady economic growth during the last 12 years, traffic on the national highways have increased 6 to 7.5% a year. The network is divided into two parts, the National Highway Development Program (NHDP) network (13,000 km) and non-NHDP network (about 45,000 km), which are managed by the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) and the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MORTH), respectively. NHAI is an implementing agency established Public Disclosure Authorized by Government of India (GOI) under the NHAI Act of 1988. -

Action Plans for the Control of Air Pollution in 15 Non-Attainment Cities

AACCTTIIOONN PPLLAANNSS FFOORR TTHHEE CCOONNTTRROOLL OOFF AAIIRR PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN IINN 1155 NNOONN--AATTTTAAIINNMMEENNTT CCIITTIIEESS OOFF UUTTTTAARR PPRRAADDEESSHH (LUCKNOW, KANPUR, AGRA, PRAYAGRAJ, VARANASI, GHAZIABAD, NOIDA, KHURZA, FIROZABAD, ANPARA, GAJRAULA, JHANSI, MORADABAD, RAEBARELI AND BAREILLY )) UUTTTTAARR PPRRAADDEESSHH PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN CCOONNTTRROOLL BBOOAARRDD TTVV--1122VV,, VVIIBBHHUUTTII KKHHAANNDD,, GGOOMMTTII NNAAGGAARR,, LLUUCCKKNNOOWW--222266002211 INDEX S.No. DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 Preface 1 2 Salient Features of the Hon'ble NGT Order 1 for preparation & Implementation of Action Plan: 3 Action Plans Implantation and approval 02 4 Salient Features of the action Plans 03 5 Responsibilities of Departments/Agencies 05 6 Monitoring and Evaluation of Action Plans 06 7 Levels Of Air Pollution and effect on human 06 health 8 National Ambient Air Quality Standards 07 9 Pollution levels/AQI can be obtained from 09 10 Ambient Air Quality of 15 Non-Attainment 10 Cities of U.P 11 Hon'ble NGT Order OA No-681 of 2018 Annex-1 12 Constitution of Air Quality Monitoring Annex-2 Committee. 13 Action Plans for 15 Non Attainment Cities Annex -3 14 Approval of Action Plan by CPCB, Delhi Annex -4 15 National Ambient Air Quality Standards Annex-5 1. Preface: Central Pollution Control Board, Delhi, on the basis of values of Particulate Matter (PM10-Particle Matter Size less than 10 micron) in ambient air has identified 15 cities of Uttar Pradesh as Non-attainment cities: 1. Lucknow 2. Kanpur 3. Agra, 4. Prayagraj 5. Varanasi, 6. Ghaziabad, 7. Noida, 8. Khurza, 9. Firozabad 10. Anpara 11. Gajraula 12. Jhansi 13. Moradabad 14. Raebareli and 15. Bareilly 2. Salient Features of the Hon'ble NGT Order for preparation & Implementation of Action Plans: Hon'ble National Green Tribunal (NGT) in O.A.No.681/2018 in News item published in "The Times of India" authored by Shri Vishwa Mohan Titled "NCAP with multiple timelines to clear air in 102 cities to be released around August 15 has given certain directions. -

The Evolution and Preservation of the Old City of Lhasa the Evolution and Preservation of the Old City of Lhasa Qing Li

Qing Li The Evolution and Preservation of the Old City of Lhasa The Evolution and Preservation of the Old City of Lhasa Qing Li The Evolution and Preservation of the Old City of Lhasa 123 Qing Li Institute of Quantitative and Technical Economics Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Beijing China ISBN 978-981-10-6733-4 ISBN 978-981-10-6735-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6735-8 Jointly published with Social Sciences Academic Press The printed edition is not for sale in China Mainland. Customers from China Mainland please order the print book from Social Sciences Academic Press. Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956325 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. and Social Sciences Academic Press 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publishers, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publishers, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Shankar Ias Academytm Prestormingtm Test 2 - Modern India - I - Explanation Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMYTM PRESTORMINGTM TEST 2 - MODERN INDIA - I - EXPLANATION KEY 1. Ans (d) Explanation: Portuguese believed that the control of the coasts were sufficient to control trade in India & didn't venture much beyond. The socio-Cultural Synthesis policy followed by Alfonso actually strengthened the Portuguese hold as marital alliances were a matter of policy. Vijayanagara Empire was of huge support to the Portuguese but it collapsed in 1565 2. Ans (c) Explanation: The Arabian Traders dominated trade with India due to their accessibility, The Portuguese therefore had to establish control to strengthen trade in the 16th century It was a Portuguese Doctrine 3. Ans (d) 4. Ans (d) 5. Ans (b) Explanation: The Britishers misused this privilege for their private trade as well. Dastak was not a tax but an exempt from tax given to the company for trade in Bengal. This system was drafted by Robert Clive and implemented by Mir Jaafar. Mir Qasim - his successor abolished it leading to confrontation with the British which eventually lead the British to bring Bengal under direct rule. 6. Ans (a) Explanation: The Governor of Bengal was to be administered with the assistance of 4 members. He was not given veto power in the 1773 act and this led to many problems for Lord Warren Hastings 7. Ans (d) Explanation: The Maratha Empire was a confederacy with multiple power centers that were subordinated to the Chatrapathi & later to the Peshwas. 8. Ans (d) Explanation: More than 90% of the global burden of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is contributed by six countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan and Sudan. -

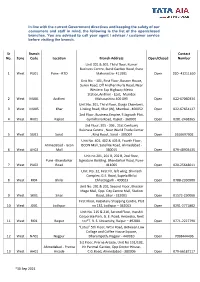

*06 Sep 2021 in Line with the Current Government Directives

In line with the current Government directives and keeping the safety of our consumers and staff in mind, the following is the list of the open/closed branches. You are advised to call your agent / advisor / customer service before visiting the branch. Sr Branch Contact No. Zone Code Location Branch Address Open/Closed Number Unit 301 & 302, Third floor, Kumar Business Centre, Bund Garden Road, Pune 1 West PU01 Pune - RTO Maharastra- 411001 Open 020- 41211610 Unit No. - 101, First Floor, Boston House, Suren Road, Off Andheri Kurla Road, Near Western Exp Highway Metro Station,Andheri - East, Mumbai 2 West MU01 Andheri Maharashtra 400 093 Open 022-67060334 Unit No. 301, Third Floor, Durga Chambers, 3 West MU05 Khar Linking Road, Khar (W), Mumbai - 400052 Open 022-67654127 2nd Floor, Business Empire, 5 Jagnath Plot, 4 West RK01 Rajkot Gymkhana Road, Rajkot - 360001 Open 0281-2468365 3rd Floor, 305 - 306 , 21st Centuary Buisness Centre , Near World Trade Center 5 West SU01 Surat , Ring Road , Surat - 395007 Open 2616697902 Unit No. 401, 402 & 403 B, Fourth Floor, Ahmedabad - Iscon ISCON Mall, Satellite Road, Ahmedabad - 6 West AH02 Mall 380015 Open 079-48903435 Unit no 201, 201 B, 202 B, 2nd floor, Pune -Bhandarkar Signature Building, Bhandarkar Road, Pune- 7 West PU02 Road 411005 Open 020-25648011 Unit No. 32, First Flr, left wing. Shivnath Complex, G.E. Road, Supela Bhilai 8 West RI04 Bhilai Chhattisgarh - 490023 Open 0788-2350900 Unit No. 201 & 202, Second Floor, Bhaskar Mega Mall, Opp. City Centre Mall, Station 9 West SK01 Sikar Road, Sikar - 332001 Open 01572-250066 First Floor, Kalpataru Shopping Centre, Plot 10 West JD01 Jodhpur no 132, Jodhpur – 342003 Open 0291-2771802 Unit No.