Working Paper-5 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Sep 2017 1412077273ER4

Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Project Location and Accessibility .............................................................................................................. 2 1.4 Project Area ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Vision statement .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.6 Scope of the Project ........................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Preliminary Appreciation of project site w.r.t surroundings and Master Paln 2021 .. 4 2.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Factor Considered for Site Selection in New Sikandrbad ..................................................................... 4 2.3 Regional Setting............................................................................................................................................... -

Roads Routes and Canal Systems

ROADS AND CANALS OF ANCIENT WORLD. ROADS From the earliest times, one of the strongest indicators of a society's level of development has been its road system-or lack of one. Increasing populations and the advent of towns and cities brought with it the need for communication and commerce between those growing population centers. A road built in Egypt by the Pharaoh Cheops around 2500 BC is believed to be the earliest paved road on record-a construction road 1,000 yards long and 60 feet wide that led to the site of the Great Pyramid. Since it was used only for this one job and was never used for travel, Cheops's road was not truly a road in the same sense that the later trade routes, royal highways, and impressively paved Roman roads were. The various trade routes, of course, developed where goods were transported from their source to a market outlet and were often named after the goods which traveled upon them. For example, the Amber Route traveled from Afghanistan through Persia and Arabia to Egypt, and the Silk Route stretched 8,000 miles from China, across Asia, and then through Spain to the Atlantic Ocean. However, carrying bulky goods with slow animals over rough, unpaved roads was a time consuming and expensive proposition. As a general rule, the price of the goods doubled for every 100 miles they had to travel. Some other ancient roads were established by rulers and their armies. The Old Testament contains references to ancient roads like the King's Highway, dating back to 2000 BC. -

Discussions on Current Social and Political Issues*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository DISCUSSIONS ON CURRENT SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ISSUES* All researchers interested in this subject are encouraged to continue the substantive discussion * Opinions of the authors of articles and commentaries in this column may not reflect the view of the publisher. Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 8 (2012 5) 1200-1217 ~ ~ ~ УДК 009 China’s Grand Strategy, Kashmir and Pakistan: Transformation of Islamabad from a Spoiler State to Frontline State for Beijing Dr. Suneel Kumar* Department of Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu Jammu-180006-Jammu and Kashmir, India 1 Received 4.11.2011, received in revised form 11.11.2011, accepted 16.07.2012 China in collaboration with Pakistan has integrated Kashmir in its grand strategy to contain India. Beijing’s involvement in various mega projects related to construction and development of strategic infrastructure in the Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir (PoK), influx of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the Gilgit-Baltistan region, adoption of visa-related controversial policies and invitation to India’s Kashmiri separatist leader, are being seen in the India’s official and strategic circles, as the encirclement of India by China through Kashmir. During the Cold War era, Beijing had bestowed Pakistan with the status of ‘spoiler state’ in order to weaken the natural predominance of India in the South Asian region. Nevertheless, now, it is being viewed that China has transformed Pakistan into a ‘ frontline state’ to contain the increasing Indian influence at regional and global levels. -

World Bank Document

Initial Project Information Document (PID) Report No: AB137 Project Name INDIA -Lucknow-Muzaffarpur National Highway Project Region South Asia Regional Office Public Disclosure Authorized Sector Roads and highways (100%) Theme Infrastructure services for private sector development (P); Public expenditure, financial management and procurement (S) Project P077856 Borrower(s) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Implementing Agency(ies) NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA Address: NHAI, Plot No. G5&G6, Sector 10, Dwarka, New Delhi Contact Person: G. R. Singhal, Chief General Manager (East-West Corridor) Tel: 91-11-2507-4100 Fax: 91-11-2508-0360 Email: [email protected] Environment Category A (Full Assessment) Date PID Prepared June 24, 2003 Auth Appr/Negs Date April 15, 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized Bank Approval Date September 30, 2004 1. Country and Sector Background Road transport plays a significant role in India's economy, carrying 80% of the land transport demand. The national highway network has a total length of 58,100 km, which accounts for about 1.8% of the total road network but carries over 40% of the road traffic. With steady economic growth during the last 12 years, traffic on the national highways have increased 6 to 7.5% a year. The network is divided into two parts, the National Highway Development Program (NHDP) network (13,000 km) and non-NHDP network (about 45,000 km), which are managed by the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) and the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MORTH), respectively. NHAI is an implementing agency established Public Disclosure Authorized by Government of India (GOI) under the NHAI Act of 1988. -

Action Plans for the Control of Air Pollution in 15 Non-Attainment Cities

AACCTTIIOONN PPLLAANNSS FFOORR TTHHEE CCOONNTTRROOLL OOFF AAIIRR PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN IINN 1155 NNOONN--AATTTTAAIINNMMEENNTT CCIITTIIEESS OOFF UUTTTTAARR PPRRAADDEESSHH (LUCKNOW, KANPUR, AGRA, PRAYAGRAJ, VARANASI, GHAZIABAD, NOIDA, KHURZA, FIROZABAD, ANPARA, GAJRAULA, JHANSI, MORADABAD, RAEBARELI AND BAREILLY )) UUTTTTAARR PPRRAADDEESSHH PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN CCOONNTTRROOLL BBOOAARRDD TTVV--1122VV,, VVIIBBHHUUTTII KKHHAANNDD,, GGOOMMTTII NNAAGGAARR,, LLUUCCKKNNOOWW--222266002211 INDEX S.No. DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 Preface 1 2 Salient Features of the Hon'ble NGT Order 1 for preparation & Implementation of Action Plan: 3 Action Plans Implantation and approval 02 4 Salient Features of the action Plans 03 5 Responsibilities of Departments/Agencies 05 6 Monitoring and Evaluation of Action Plans 06 7 Levels Of Air Pollution and effect on human 06 health 8 National Ambient Air Quality Standards 07 9 Pollution levels/AQI can be obtained from 09 10 Ambient Air Quality of 15 Non-Attainment 10 Cities of U.P 11 Hon'ble NGT Order OA No-681 of 2018 Annex-1 12 Constitution of Air Quality Monitoring Annex-2 Committee. 13 Action Plans for 15 Non Attainment Cities Annex -3 14 Approval of Action Plan by CPCB, Delhi Annex -4 15 National Ambient Air Quality Standards Annex-5 1. Preface: Central Pollution Control Board, Delhi, on the basis of values of Particulate Matter (PM10-Particle Matter Size less than 10 micron) in ambient air has identified 15 cities of Uttar Pradesh as Non-attainment cities: 1. Lucknow 2. Kanpur 3. Agra, 4. Prayagraj 5. Varanasi, 6. Ghaziabad, 7. Noida, 8. Khurza, 9. Firozabad 10. Anpara 11. Gajraula 12. Jhansi 13. Moradabad 14. Raebareli and 15. Bareilly 2. Salient Features of the Hon'ble NGT Order for preparation & Implementation of Action Plans: Hon'ble National Green Tribunal (NGT) in O.A.No.681/2018 in News item published in "The Times of India" authored by Shri Vishwa Mohan Titled "NCAP with multiple timelines to clear air in 102 cities to be released around August 15 has given certain directions. -

Shankar Ias Academytm Prestormingtm Test 2 - Modern India - I - Explanation Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMYTM PRESTORMINGTM TEST 2 - MODERN INDIA - I - EXPLANATION KEY 1. Ans (d) Explanation: Portuguese believed that the control of the coasts were sufficient to control trade in India & didn't venture much beyond. The socio-Cultural Synthesis policy followed by Alfonso actually strengthened the Portuguese hold as marital alliances were a matter of policy. Vijayanagara Empire was of huge support to the Portuguese but it collapsed in 1565 2. Ans (c) Explanation: The Arabian Traders dominated trade with India due to their accessibility, The Portuguese therefore had to establish control to strengthen trade in the 16th century It was a Portuguese Doctrine 3. Ans (d) 4. Ans (d) 5. Ans (b) Explanation: The Britishers misused this privilege for their private trade as well. Dastak was not a tax but an exempt from tax given to the company for trade in Bengal. This system was drafted by Robert Clive and implemented by Mir Jaafar. Mir Qasim - his successor abolished it leading to confrontation with the British which eventually lead the British to bring Bengal under direct rule. 6. Ans (a) Explanation: The Governor of Bengal was to be administered with the assistance of 4 members. He was not given veto power in the 1773 act and this led to many problems for Lord Warren Hastings 7. Ans (d) Explanation: The Maratha Empire was a confederacy with multiple power centers that were subordinated to the Chatrapathi & later to the Peshwas. 8. Ans (d) Explanation: More than 90% of the global burden of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is contributed by six countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan and Sudan. -

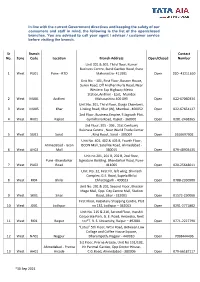

*06 Sep 2021 in Line with the Current Government Directives

In line with the current Government directives and keeping the safety of our consumers and staff in mind, the following is the list of the open/closed branches. You are advised to call your agent / advisor / customer service before visiting the branch. Sr Branch Contact No. Zone Code Location Branch Address Open/Closed Number Unit 301 & 302, Third floor, Kumar Business Centre, Bund Garden Road, Pune 1 West PU01 Pune - RTO Maharastra- 411001 Open 020- 41211610 Unit No. - 101, First Floor, Boston House, Suren Road, Off Andheri Kurla Road, Near Western Exp Highway Metro Station,Andheri - East, Mumbai 2 West MU01 Andheri Maharashtra 400 093 Open 022-67060334 Unit No. 301, Third Floor, Durga Chambers, 3 West MU05 Khar Linking Road, Khar (W), Mumbai - 400052 Open 022-67654127 2nd Floor, Business Empire, 5 Jagnath Plot, 4 West RK01 Rajkot Gymkhana Road, Rajkot - 360001 Open 0281-2468365 3rd Floor, 305 - 306 , 21st Centuary Buisness Centre , Near World Trade Center 5 West SU01 Surat , Ring Road , Surat - 395007 Open 2616697902 Unit No. 401, 402 & 403 B, Fourth Floor, Ahmedabad - Iscon ISCON Mall, Satellite Road, Ahmedabad - 6 West AH02 Mall 380015 Open 079-48903435 Unit no 201, 201 B, 202 B, 2nd floor, Pune -Bhandarkar Signature Building, Bhandarkar Road, Pune- 7 West PU02 Road 411005 Open 020-25648011 Unit No. 32, First Flr, left wing. Shivnath Complex, G.E. Road, Supela Bhilai 8 West RI04 Bhilai Chhattisgarh - 490023 Open 0788-2350900 Unit No. 201 & 202, Second Floor, Bhaskar Mega Mall, Opp. City Centre Mall, Station 9 West SK01 Sikar Road, Sikar - 332001 Open 01572-250066 First Floor, Kalpataru Shopping Centre, Plot 10 West JD01 Jodhpur no 132, Jodhpur – 342003 Open 0291-2771802 Unit No. -

Annual Report 2019-20

Annual Report 2019-20 Contents Chairman’s Letter .................................... 4 Company Information ............................. 11 Management Discussion & Analysis ...... 12 Corporate Governance ............................ 21 Board’s Report ........................................ 41 Business Responsibility Report .............. 70 Standalone Auditors’ Report ................... 76 Standalone Financial Statements ............ 90 Consolidated Auditors’ Report ............... 163 Consolidated Financial Statements ........ 176 Notice ...................................................... 288 Highlights 2019-20 • Turnover: `3643.64 crore in FY20 vs. `4603.49 crore in FY19 • EBITDA margin (excluding Other Income) was 12.7% in FY20 vs. 12.8% in FY19 • Net Loss of `168.7 crore compared to Loss of `1925.6 crore in FY19 • Infusions of liquidity in FY20: `348 crore arbitration award collections • Senior lenders approved carve out ~`2,800 crore of Debt along with pool of Awards/Claims, to address Company’s asset-liability mismatch • Supreme Court struck down Section 87 of Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 1996, on Nov 27, 2019, freeing HCC to execute awards of `1,584 crore • CCEA amendment circular dt. Nov 20, 2019 to help accelerate realization of arbitral awards; Govt. agencies to take the opinion of Law Officer before challenging arbitral awards and requiring a refund of BGs given for interest component (~`850 crore in HCC’s case) • Conciliations of Awards/Claims of ~Rs.5,000 crore underway with NHAI • Robust free cash flow -

India's Top 20 Promising Cities

SM@RT CITIES COUNCIL www.ConstructionWorld.inwww.ConstructionWorld.in COVER STORY SURAT NAGPUR LUCKNOW VADODARA VISAKHAPATNAM THANE JAIPUR PIMPRI CHINCHWAD INDIA’S TOP 20 PROMISING CITIES CHANDIGARH INDORE NAVI MUMBAI KANPUR KALYAN-DOMBIVLI FARIDABAD GURGAON GHAZIABAD 2 Construction World March 2013 1 RAJKOT BHOPAL LUDHIANA NASHIK SM@RT CITIES COUNCIL ndia in 2012: 153 rural, 219 transition, 84 semi-urban and 33 urban (Punjab), and Nashik (Maharashtra). In fact, representatives of these cities – districts (excluding the Northeast states and Jammu & Kashmir). And in their municipal chiefs – will be awarded at the upcoming Sm@rt Cities Summit 2025: 96 rural, 220 transition, 115 semi-urban and 58 urban districts. to be held in New Delhi in February and organised by FIRST Sm@rt Cities Council. These numbers from McKinsey & Company’s recent report, India’s Economic Geography in 2025: States, Clusters and Cities, attest to the Commissionerspeak Icountry’s growing urban sprawl. Attendant woes, though, include a big city So what makes these cities so promising? We spoke to some of their bias with the major cities consuming a bulk of natural and financial resources representatives for the answer. as well as unplanned development. As Prof Jagan Shah, Director, National For instance, Dr Amit Agrawal, Municipal Commissioner, Municipal Institute of Urban Affairs, says, “This has resulted in the sprawling of Corporation Faridabad, tells us how his city holds great promise to be a good existing urban centres with haphazard growth patterns and a corrosive effect urban centre. “The most important factor is the city’s location and connectivity,” on the surrounding region.” he reasons. -

Status of Industrial Settlement of Gurgaon and Faridabad (NCR, Haryana)

International Journal of Advancements in Research & Technology, Volume 2, Issue1, January-2013 1 ISSN 2278-7763 Status of Industrial Settlement of Gurgaon and Faridabad (NCR, Haryana) Tarun Punia, Jasbeer Cheema National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS), Ministry of HRD, Govt. of India Noida-201309 (U.P.) E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Development of a country can be judged through the development of its economy. The country having strong economy is considered as a developed country. Earlier Indian economy was totally dependent on agriculture but now the interest of our economy shifts toward industry. Industry is a place where raw material is converted to finished product but Industrialization is essentially a process of technological innovation which leads to improved organization, specialization, division of labour, which has inherent impulses of faster, continuous and cumulative growth (Hermansen, 1971 vide Prasad, 1974). Industrialization play vital and crucial role in the economic development of a Country. Earlier Industrialization was very slow in India but now with the passage of time it speeds up.But there is significant development in National Capital Region of Haryana. Industrial development is taking place at a very high pace in Gurgaon and Faridabad as compared to other parts of Haryana state. In light of the above, the present paper would mainly focus on status of industrial settlement of Gurgaon and Faridabad (NCR, Haryana). Keywords: NCR, Industrial development, Settlement and Clusters. 1 INTRODUCTION Settlement is dwelling place of an individual where Ludhiana city (Punjab) is the best example of this he lives in interaction with other individuals and type of settlement. -

13 to 19 August 2012

Topic of the week for discussion: 13th to 19 th August 2012 Topic: 33 lakh km Roads - Life Line of India History of Indian roads is quite old. Ruling emperors and monarchs of ancient India had constructed numerous brick roads in the cities. One of the most famous highways of medieval India is the Grand Trunk Road. The Grand Trunk Road began in Sonargaon near Dhaka in Bangladesh and ended at Peshawar in modern-day Pakistan. In India, it linked several important cities from Kolkata in the east to Amritsar in the west, while passing through the cities of Patna, Varanasi, Kanpur, Agra, Delhi, Panipat, Ambala, Ludhiana and Jalandhar. At the time of independence, India inherited a poor road network infrastructure from Britain. Between 1947 and 1988, India witnessed no new major road development projects and there was poor maintenance of the existing ones. Predominantly all roads were single lane and mostly unpaved. India had no expressways and less than 200 kilometers of 4-lane highways. Topic In 1988, the National Highways Authority of India was established in India by an Act of Parliament. This autonomous entity came into existence on Introduction 15th June, 1989. The Act empowered this entity to develop, maintain and manage India’s road network through National Highways. However, even though the Authority was created in 1988, nothing much happened till India introduced widespread economic liberalization in early 1990s. Since 1995, the authority has privatized road network development in India. As a result over 70,000 kilometres of National Highways have been built by December 2011 out of which 16,500 kilometers are 4-lane or 6-lane modern highways. -

Development Coordination

Rural Connectivity Investment Program (RRP IND 40423) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. External assistance to roads in India has been substantial. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has provided loans as well as technical assistance (TA) of about $4.5 billion. The World Bank has provided loans and grants totaling about $6.5 billion for upgrading national highways and rural roads, and improving state highways. The Japan International Cooperation Agency has provided six loans for a total of around $765 million to upgrade national highways and construct bridges. The Government of the United Kingdom has provided TA to support the sector. Roads Projects of Major Development Partners in India A. ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Region/State Project Name Year $ Million Approved Equivalent Various states Road Improvement (Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, 1988 198 Andra Pradesh, Karnataka) Various states Second Road (Karnataka, Kerala, Rajasthan, Andra 1990 250 Pradesh, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal) Various states National Highways (Bihar, West Bengal, Haryana, Rajasthan, Andra Pradesh) 1993 245 (Consultancy) Bombay-Vadora Expressway Technical Assistance 1993 0 Gujarat, Maharashtra Surat-Manor Tollway 2000 180 Karnataka Western Transport Corridor 2001 240 West Bengal West Bengal Corridor Development 2001 210 Gujarat East-West Corridor 2002 320 Madhya Pradesh State Roads Sector Development Madhya Pradesh Program (Program Loan) 2002 30 Madhya Pradesh State Roads Sector Development Madhya Pradesh