Emergency Radiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomical Overview

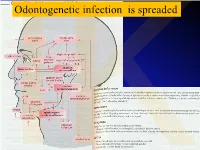

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

MSS 1. a Patient Presented to a Traumatologist with a Trauma Of

MSS 1. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of shoulder. What wall of axillary cavity contains foramen trilaterum and foramen quadrilaterum? a) anterior b) posterior c) lateral d) medial e) intermediate 2. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of leg, which he had sustained at a sport competition. Upon examination, damage of posterior muscle, that is attached to calcaneus by its tendon, was found. This muscle is: a) triceps surae b) tibialis posterior c) popliteus d) fibularis longus e) fibularis brevis 3. In the course of a cesarean section, an incision was made in the pubic area and vagina of rectus abdominis muscle was cut. What does anterior wall of the vagina of rectus abdominis muscle consist of? A. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis. B. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. pyramidalis. C. aponeurosis of m. obliquus internus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. D. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. E. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis 4. A 30 year-old woman complained of pain in the lower part of her forearm. Traumatologist found that her radio-carpal joint was damaged. This joint is: A. complex, ellipsoid B.simple, ellipsoid C.complex, cylindrical D.simple, cylindrical E.complex condylar 5. A woman was brought by an ambulance to the emergency department with a trauma of the cervical part of her vertebral column. Radiologist diagnosed a fracture of a nonbifid spinous processes of one of her cervical vertebrae. Spinous process of what cervical vertebra is fractured? A.VI. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0 Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University SPLANCHNOLOGY, CARDIOVASCULAR AND IMMUNE SYSTEMS STUDY GUIDE Recommended by the Academic Council of Sumy State University Sumy Sumy State University 2016 1 УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 С72 Composite authors: V. I. Bumeister, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor; L. G. Sulim, Senior Lecturer; O. O. Prykhodko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant; O. S. Yarmolenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant Reviewers: I. L. Kolisnyk – Associate Professor Ph. D., Kharkiv National Medical University; M. V. Pogorelov – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Sumy State University Recommended for publication by Academic Council of Sumy State University as а study guide (minutes № 5 of 10.11.2016) Splanchnology Cardiovascular and Immune Systems : study guide / С72 V. I. Bumeister, L. G. Sulim, O. O. Prykhodko, O. S. Yarmolenko. – Sumy : Sumy State University, 2016. – 253 p. This manual is intended for the students of medical higher educational institutions of IV accreditation level who study Human Anatomy in the English language. Посібник рекомендований для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів IV рівня акредитації, які вивчають анатомію людини англійською мовою. УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 © Bumeister V. I., Sulim L G., Prykhodko О. O., Yarmolenko O. S., 2016 © Sumy State University, 2016 2 Hippocratic Oath «Ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν, καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν, καὶ Ὑγείαν, καὶ Πανάκειαν, καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ ξυγγραφὴν τήνδε. -

TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 Thru 49999 Page Updated: January 2021

tar and non cd4 1 TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 Page updated: January 2021 Surgery Digestive System Note: Refer to the TAR and Non-Benefit: Introduction to List in this manual for more information about the categories of benefit restrictions. Lips Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40490 Biopsy of lip Assistant Surgeon services not payable Other Procedures Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40799 Unlisted procedure, lips Requires TAR, Primary Surgeon/ Provider Vestibule of Mouth Incision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40800 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40801 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, complicated Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40804 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40805 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, Assistant Surgeon complicated services not payable 40806 Incision labial frenum Non-Benefit Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40808 Biopsy, vestibule of mouth Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40810 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, without Non-Benefit repair Part 2 – TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 tar and non cd4 2 Page updated: January 2021 Excision (continued) Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40812 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon repair services not payable 40816 Excision of lesion, mouth, mucosa/submucosa, Assistant Surgeon complex services not payable 40819 Excision of frenum, labial -

Deep Neck Space Infection

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 DEEP NECK SPACE INFECTION- A CLINICAL INSIGHT Correspondance to:Dr.Vijay Ebenezer 1, Professor Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. Email id: [email protected], Contact no: 9840136328 Names of the author(s): 1)Dr. Vijay Ebenezer1 ,Professor and Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree Balaji dental college and hospital , BIHER, Chennai-600100, Tamilnadu , India. 2)Dr. Balakrishnan Ramalingam2, professor in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. INTRODUCTION Deep neck infections are a life threatening condition but can be treated, the infections affects the deep cervical space and is characterized by rapid progression. These infections remains as a serious health problem with significant morbidity and potential mortality. These infections most frequently has its origin from the local extension of infections from tonsils, parotid glands, cervical lymph nodes, and odontogenic structures. Classically it presents with symptoms related to local pressure effects on the respiratory, nervous, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract (particularly neck mass/swelling/induration, dysphagia, dysphonia, and trismus). The specific presenting symptoms will be related to the deep neck space involved (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, prevertebral, submental, masticator, etc).1,2,3,4,5 ETIOLOGY Deep neck space infections are polymicrobial, with their source of origin from the normal flora of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. The most common deep neck infections among adults arise from dental and periodontal structures, with the second most common source being from the tonsils. -

Neck Formation and Growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS in NECK

Neck formation and growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS IN NECK. ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND FOR URGENT LIFE SAVING PERFORMANCES. orofac Ivo Klepáček orofac Vymezení oblasti krku Extent of the neck region Sensitivní oblasti V1, V2, V3., plexus cervicalis orofac * * * * * orofac** * orofac orofac orofaccranial middle caudal orofac orofac Clinical classification of neck lymph nodes orofacClinical classification of neck lymphatic nodes: I - VI Nodi lymphatici out of regiones above: Perifacial, periparotic, retroauricular, suboccipital, retropharyngeal Metastasa v krčních uzlinách Metastasis in cervical orofaclymphonodi TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS orofacand SPACES Regio colli anterior anterior neck triangle Trigonae : submentale, submandibulare, caroticum (musculare), regio suprasternalis Triangles : submental, submandibular, carotic (muscular), orofacsuprasternal region podkožní sval na povrchové krční fascii r. colli nervi facialis ovládá napětí kůže krku Platysma orofac proc. mastoideus manubrium sterni, clavicula Sternocleidomastoid m. n.accessorius (XI) + branches sternocleidomastoideus from plexus cervicalis orofac Punctum nervosum (Erb ´s point) : there C5 and C6 nerves are connected, + branches from suprascapulari and subclavian nerves orofacWilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840 - 1921), German neurologist orofac orofac mm. suprahyoid suprahyoidei and et mm. infrahyoid orofacinfrahyoidei muscles orofac Thyroid gland and vascular + nerve bundle in neck orofac orofac Žíly veins orofac štítná žláza příštitné orofactělísko a. thyroidea inferior n. laryngeus inferior -

Surgical Approaches to the Submandibular Gland: a Review of Literatureq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector International Journal of Surgery 7 (2009) 503–509 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery journal homepage: www.theijs.com Review Surgical approaches to the submandibular gland: A review of literatureq David D. Beahm a, Laura Peleaz a, Daniel W. Nuss a,b,c, Barry Schaitkin b, Jayc C. Sedlmayr c, Carlos Mario Rivera-Serrano b, Adam M. Zanation d, Rohan R. Walvekar a,* a Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, LSU Health Science Center, 533 Bolivar Street, Suite 566 New Orleans, LA 70112, United States b Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States c Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, United States d Department of Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC article info abstract Article history: Objectives: Surgical excision of the submandibular gland (SMG) is commonly indicated in patients with Received 4 July 2009 neoplasms, and non-neoplastic conditions such as chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, ranula and drooling. Received in revised form Traditional SMG surgery involves a direct transcervical approach. In the recent past, alternative approaches to 4 September 2009 SMG excision have been described in effort to offer minimally invasive options or better cosmetic results. The Accepted 12 September 2009 purpose of this article is to describe the surgical approaches to the SMG and present relevant surgical anatomy Available online 24 September 2009 via cadaveric dissection and a systematic review of literature to compare and contrast each technique. -

Clinical Anatomy of the Neck Region

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA STATE UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY "NICOLAE TESTEMIȚANU" DEPARTMENT TOPOGRAPHIC ANATOMY AND OPERATIVE SURGERY Gheorghe GUZUN, Radu TURCHIN, Boris TOPOR, Serghei SUMAN CLINICAL ANATOMY OF THE NECK REGION Methodical recommendations for students CHISINAU, 2017 CZU 611.93(076.5) C 57 Lucrarea a fost aprobată de Consiliul Metodic Central al USMF “Nicolae Testemițanu”; proces-verbal nr. 2 din 10.03.2017 Autori: Gheorghe GUZUN – dr. med, conf. univ. Radu TURCHIN – dr.șt.med., conf. univ. Boris TOPOR – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Serghei SUMAN – dr.hab.șt.med., conf. univ. Recenzenți: Ilia catereniuc – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Nicolae Fruntașu – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Machetare: Serghei Suman – dr.hab.șt.med., conf. univ. DESCRIEREA CIP A CAMEREI NAȚIONALE A CĂRȚII Clinical anatomy of the neck region : Methodical recommendations for students / Gheorghe Guzun, Radu Turchin, Boris Topor [et al.] ; State Univ. of Medicine and Pharmacy "Nicolae Testemiţanu", Dep. Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery. – Chişinău : S. n., 2017 (Tipogr. "Print-Caro"). – 52 p. : fig. 100 ex. ISBN 978-9975-56-466-3. 611.93(076.5) C 57 ISBN 978-9975-56-466-3. CEP Medicina, 2017 Gheorghe Guzun, Radu Turchin, Viorel Nacu, Boris Topor, 2017. © Gheorghe Guzun, 2017 CLINICAL ANATOMY OF THE NECK The upper limit of the neck (cefalocervical limit) is a conventional line that crosses the lower jaw (basis of mandible) and its angle, the bottom of the external auditory canal, the apex of mastoid process (procesuus mastoideus) and superior nuchal line (linea nuchae superior) to the external occipital protuberance (occipitalis external protuberance). -

Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa

Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa Best Clinical Practice Guidelines October 2011 Oral Health Care for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa Best Clinical Practice Guidelines October 2011 Clinical Editor: Susanne Krämer S. Methodological Editor: Julio Villanueva M. Authors: Prof. Dr. Susanne Krämer Dr. María Concepción Serrano Prof. Dr. Gisela Zillmann Dr. Pablo Gálvez Prof. Dr. Julio Villanueva Dr. Ignacio Araya Dr. Romina Brignardello-Petersen Dr. Alonso Carrasco-Labra Prof. Dr. Marco Cornejo Mr. Patricio Oliva Dr. Nicolás Yanine Patient representatives: Mr. John Dart Mr. Scott O’Sullivan Pilot: Dr. Victoria Clark Dr. Gabriela Scagnet Dr. Mariana Armada Dr. Adela Stepanska Dr. Renata Gaillyova Dr. Sylvia Stepanska Review: Prof. Dr. Tim Wright Dr. Marie Callen Dr. Carol Mason Prof. Dr. Stephen Porter Dr. Nina Skogedal Dr. Kari Storhaug Dr. Reinhard Schilke Dr. Anne W Lucky Ms. Lesley Haynes Ms. Lynne Hubbard Mr. Christian Fingerhuth Graphic design: Ms. Isabel López Production: Gráfica Metropolitana Funding: DEBRA UK © DEBRA International This work is subject to copyright. ISBN-978-956-9108-00-6 Versión On line: ISBN 978-956-9108-01-3 Printed in Chile in October 2011 Editorial: DEBRA Chile Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Coni V., María Elena, María José, Daniela, Annays, Lisette, Victor, Coni S., Esteban, Coni A., Felipe, Nibaldo, María, Cristián, Deyanira and Victoria for sharing their smile to make these Guidelines more friendly. 4 Contents 1 Introduction 07 2 Oral care for patients with Inherited Epidermolysis Bullosa 11 3 Dental treatment 19 4 Anaesthetic management 29 5 Summary of recommendations 33 Development of the guideline 37 6 Appendix 43 7.1 List of abbreviations and glossary 7.2 Oral manifestations of Epidermolysis Bullosa 7 7.3 General information on Epidermolysis Bullosa 7.4 Exercises for mouth, jaw and tongue 8 References 61 5 A message from the patient representative: “Be guided by the professionals. -

Rare Case of Plunging Ranula with Parapharyngeal Extension and Absent Submandibular Gland: Excision by Transcervical Approach

Central Journal of Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report *Corresponding author Abhishek Bhardwaj, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Safdarjung Hospital Rare Case of Plunging Ranula &Vardhmann Mahavir Medical College, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi-110029, India, Tel: 91-989907792; Email: with Parapharyngeal Extension Submitted: 04 January 2017 Accepted: 29 March 2017 and Absent Submandibular Published: 31 March 2017 ISSN: 2475-9473 Copyright Gland: Excision by Transcervical © 2017 Bhardwaj et al. Approach OPEN ACCESS Keywords Abhishek Bhardwaj*, Sudhagar Eswaran, and Hari Shankar • Ranula Niranjan • Submandibular gland Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Vardhmann Mahavir Medical College and • Pharynx Safdarjung Hospital, India • Skull Base • Neck Abstract Plunging ranula extending into parapharyngeal space till the skull base with associated absence of submandibular gland is a rare finding. Transcervical approach for its excision is a challenging procedure in view of limited exposure and presence of important neurovascular structures in the field. We present a clinical case of a left sided plunging ranula extending into the parapharyngeal space till skull base in a 19 year old male who presented to a tertiary care hospital with complaints of slowly increasing swelling in neck and oral cavity for duration of six months. Ultrasound neck revealed well defined heterogeneously hypoechoic collection in left submandibular region. Contrast enhanced computed tomography revealed a non-enhancing, cystic mass involving left submandibular space extending into left parapharyngeal space till skull base and absent left submandibular gland. Ranula measuring 10cm*6cm was excised in to by tanscervical approach without damage to any neurovascular structure. Histopathology was consistent with low ranula. Patient is in follow up for past six months without any recurrence.