A Report of the CSIS Task Force on Gulf of Guinea Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addressing the Atlantic's Emerging Security Challenges

34 Addressing the Atlantic’s Emerging Security Challenges Bruno Lété The German Marshall Fund of the United States ABSTRACT As the Atlantic space is expected to continue to play a global role, it is not surprising that nations around the Atlantic have become increasingly concerned about securing the region’s commons at land, at sea, and in the air. In much contrast to the territorial disputes and military tensions defining the Pacific Rim, the Atlantic remains a relatively stable geo-political sphere, largely due to the lack of great power conflict. But the prominence of the region in security and military considerations is rising, especially with the aim to combat illegal activities. This paper identifies three emerging security challenges that may jeopardize the future peace and prosperity of all the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean if they are left unresolved. The first draft of this Scientific Paper was presented at the ATLANTIC FUTURE Seminar, Lisbon, 24 April 2015 ATLANTIC FUTURE SCIENTIFIC PAPER 34 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 2. The Atlantic remains a key region in a rapidly changing global system ...................................................................................................... 3 3. Three emerging challenges affect security in the Atlantic ....... 4 4. A pan-Atlantic approach is lacking ...................................................... 9 5. Conclusion .................................................................................................. -

EQUATORIAL GUINEA Malabo Vigatana

Punta Europa EQUATORIAL GUINEA Malabo Vigatana Basupú San Antonio Basapú Rebola Sampaca de Palé Basilé Baney I. Tortuga Balorei BIOKO NORTE Cupapa Ye Cuín Basuala ATLANTIC Isla de Batoicopo OCEAN Pico Basilé Annobón 3,011.4 m Basacato Bacake Pequeño Lago a Pot del Oeste ATLANTIC OCEAN Baó Grande ANNOBÓN Anganchi BIOKO SUR Moeri Bantabare Quioveo Batete 598 m National capital Luba Bombe Isla de Boiko (Fernando Po) Provincial capital Musola Bococo Aual City, town Riaba Major airport Caldera 2,261 m International boundary Malabo Misión Mábana Provincial boundary Eoco Main road Bohé Other road or track Ureca 0 1 2 km The seven provinces are grouped into 0 5 10 15 20 km two regions: Continental, chief town Bata; and Insular, chief town Malabo. 0 1 mi 0 5 10 mi Punta Santiago Río Ntem Punta Epote B ongola The boundaries and names shown and the CAMEROON Tica designations used on this map do not imply official Yengüe CAMEROON endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Bioko N etem Macora EQUATORIAL Andoc Ebebiyin Ayamiken Ngoa Micomeseng Acom Esong GUINEA Mbía Anguma Mimbamengui KIE NTEM GABON Ebongo Nsang Biadbe San Joaquín Nkue Tool Annobón lo de Ndyiacon San o Dumandui G B Utonde Carlos Oboronco u Mfaman Temelon a o Abi r Ngong Monte Bata o Mongo Bata Ngosoc ATLANTIC Nfonga Mindyiminue Niefang Añisok OCEAN Mfaman Niefang Nonkieng Ayaantang Movo Mondoc Efualn Elonesang Ndumensoc Amwang Ncumekie LITORAL Bisún Mbam Pijaca Nyong Masoc Ayabene Bingocom ito Manyanga en Mongomo B Añisoc Mbini Bon Ncomo Nkumekie Yen U Nsangnam o ro Mbini Mangala -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

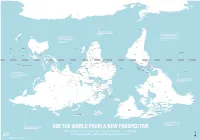

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR -

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea Location and Size Equatorial Guinea consists of a land area that is part of mainland Africa and a series of islands off the coast of the Gulf of Guinea. Equatorial Guinea is located in West Africa, bordering the Bight of Biafra, between Cameroon and Gabon. The country lies at 4o 00 N, 10o 00 E. Equatorial Guinea is positioned within the extreme coordinates of 4°00 N and 2°00S and 10° 00E and 8° 00E Equatorial Guinea has a total land area of 28,051 sq km. The mainland territory of the country is called Rio Muni. The island territories of the country are: Bioko (formally, Fernando Po), Annobon, Corisco, Belobi, Mbane, Conga, Cocotiers, Elobey Island (formally known as Mosquito Islands). Rio Muni (Equatorial Guinea’s Continental Territory) Rio Muni is a rectangular-shaped territory measuring about 26,000 sqkm (16,150 sq Miles). Rio Muni, which is the mainland territory of Equatorial Guinea lies at 1o01’ and 2o21’N. The eastern borderline of Rio Muni lies approximately on longitude 11o20E. This territory is bordered by Gabon on the south and east, Cameroon on the north, and the Atlantic Ocean on the west. The Islands of Corisco (14 sq. km), Belobi, Mbane, Conga, Cocotiers, and Elobey (2 sq. km) are all within the territorial area of Rio Muni. Bioko Bioko, formally Fernando Po, is the largest of the series of islands that constitute part of Equatorial Guinea. Bioko is rectangular in shape and lies at 3° 30' 0 N and 8° 41' 60 E. The island lies 32 km from Mount Cameroon. -

195 the Gulf of Guinea

THE GULF OF GUINEA: THE NEW DANGER ZONE Africa Report N°195 – 12 December 2012 Translation from French TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. A STRATEGIC REGION IN THE GRIP OF INSECURITY ...................................... 2 A. RENEWED STRATEGIC INTEREST IN NATURAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 2 B. A CONTEXT FAVOURABLE TO MARITIME CRIME ......................................................................... 3 C. WEAK MARITIME POLICIES .......................................................................................................... 4 III. NIGERIA: EPICENTRE OF VIOLENCE AT SEA ...................................................... 6 A. POOR GOVERNANCE AND MARITIME CRIME ................................................................................ 6 1. A leaky oil sector ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. The rise in economic crime .......................................................................................................... 7 3. State capacity hampered by corruption ........................................................................................ 8 4. The Niger Delta ........................................................................................................................... -

4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣

CHAPTER I OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA 4 European Policy and Energy Interests – Challenges from the Gulf of Guinea ␣ By Lutz Neumann 1. Introduction ␣ The Gulf of Guinea has great oil and gas potential. While predictions on Africa should be made with some care, analysts and representatives of the oil industry appear to agree that the region belongs to those areas where production will rapidly increase in the coming years and decades. Output figures of the chief oil- producing countries, Nigeria and Angola, are expected to double or triple within the next decade and thus will cause certain dynamics on the shaping of trade movements (see table 1). Table 1: Projected Oil Production of Gulf of Guinea 2005-2030 (in b/d) 2005 2010 2015 2030 Nigeria 2,719,000 3,042,000 3,729,000 4,422,000 Angola 1,098,000 2,026,000 2,549,000 3,288,000 Equatorial-Guinea 313,000 466,000 653,000 724,000 Congo (Brazzaville) 285,000 300,000 314,000 327,000 Gabon 303,000 291,000 279,000 269,000 Côte d’Ivoire 43,000 71,000 83,000 94,000 Cameroun 84,000 72,000 66,000 61,000 Congo (Kinshasa) 30,000 33,000 30,000 25,000 Ghana 11,000 16,000 20,000 23,000 Total Africa 9,936,000 12,059,000 13,975,000 16,242,000 Source: EIA, U.S. Department of Energy.␣ FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG 59 OIL POLICY IN THE GULF OF GUINEA CHAPTER I The African countries along the Atlantic coast represent a growing supplier region. -

Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations Along Its Northern Coasts During the Boreal Summer Period

Asian Journal of Applied Sciences 4 (3): 271-285, 2011 ISSN 1996-3343 I DOI: 10.3923/ajaps.2011.271.285 © 2011 Knowledgia Review, Malaysia Influence of the Gulf of Guinea Coastal and Equatorial Upwellings on the Precipitations along its Northern Coasts during the Boreal Summer Period 'K.E. Ali, 'K.Y. Kouadio, 'E.-P. Zahiri, 'A. Aman, 'A.P. Assamoi and 2B. Bourles 'LAPAMF, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan BP 231 Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire 2IRD/LEGOS-CRHOB, Representation !RD, 08 BP 841 Cotonou, Republique du Benin Corresponding Author: Angora Aman, Universite de Cocody-Abidjan 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, LAPA-MF, UFR-SSMT, Cote d'Ivoire Tel: (225) 07 82 77 52 Fax: (225) 22 44 14 07 ABSTRACT The Gulf of Guinea (GG) is an area where a seasonal upwelling takes place, along the equator and its northern coasts between Benin and Cote d'Ivoire. The coastal upwelling has a real impact on the local yet documented biological resources. However, climatic impact studies of this seasonal upwelling are paradoxically very rare and disseminated and this impact is still little known, especially on the potential part played by the upwelling onset on the regional precipitation in early boreal summer. This study shows that coastal precipitations of the July-September period are correlated by both the coastal and equatorial sea-surface temperatures (SSTS). This correlation results in a decrease or a rise of rainfall when the SSTs are abnormally cold or warm respectively. The coastal areas that are more subject to coastal and equatorial SSTs influence are located around the Cape Three Points, where the coastal upwelling exhibits the maximum of amplitude. -

Atlantic Ocean Equatorial Currents

188 ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS ATLANTIC OCEAN EQUATORIAL CURRENTS S. G. Philander, Princeton University, Princeton, Centered on the equator, and below the westward NJ, USA surface Sow, is an intense eastward jet known as the Equatorial Undercurrent which amounts to a Copyright ^ 2001 Academic Press narrow ribbon that precisely marks the location of doi:10.1006/rwos.2001.0361 the equator. The undercurrent attains speeds on the order of 1 m s\1 has a half-width of approximately Introduction 100 km; its core, in the thermocline, is at a depth of approximately 100 m in the west, and shoals to- The circulations of the tropical Atlantic and PaciRc wards the east. The current exists because the west- Oceans have much in common because similar trade ward trade winds, in addition to driving divergent winds, with similar seasonal Suctuations, prevail westward surface Sow (upwelling is most intense at over both oceans. The salient features of these circu- the equator), also maintain an eastward pressure lations are alternating bands of eastward- and west- force by piling up the warm surface waters in the ward-Sowing currents in the surface layers (see western side of the ocean basin. That pressure force Figure 1). Fluctuations of the currents in the two is associated with equatorward Sow in the thermo- oceans have similarities not only on seasonal but cline because of the Coriolis force. At the equator, even on interannual timescales; the Atlantic has where the Coriolis force vanishes, the pressure force a phenomenon that is the counterpart of El Ninoin is the source of momentum for the eastward Equa- the PaciRc. -

Articles from the Free Tropo

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 5373–5390, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5373-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Downward cloud venting of the central African biomass burning plume during the West Africa summer monsoon Alima Dajuma1,3, Kehinde O. Ogunjobi1,4, Heike Vogel2, Peter Knippertz2, Siélé Silué5, Evelyne Touré N’Datchoh3, Véronique Yoboué3, and Bernhard Vogel2 1Department of Meteorology and Climate Sciences, West African Science Service Centre on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use (WASCAL), Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), Ondo State, Nigeria 2Institute of Meteorology and Climate Research, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany 3University Félix Houphouët Boigny, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 4Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), Ondo State, Nigeria 5Université Peleforo Gon Coulibaly, Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire Correspondence: Alima Dajuma ([email protected]) Received: 29 June 2019 – Discussion started: 9 August 2019 Revised: 3 April 2020 – Accepted: 4 April 2020 – Published: 7 May 2020 Abstract. Between June and September large amounts of clouds and rainfall over the Gulf of Guinea. Using the CO biomass burning aerosol are released into the atmosphere dispersion as an indicator for the biomass burning plume, we from agricultural fires in central and southern Africa. Re- identify individual mixing events south of the coast of Côte cent studies have suggested that this plume is carried west- d’Ivoire due to midlevel convective clouds injecting parts of ward over the Atlantic Ocean at altitudes between 2 and the biomass burning plume into the PBL. Idealized tracer ex- 4 km and then northward with the monsoon flow at low lev- periments suggest that around 15 % of the CO mass from els to increase the atmospheric aerosol load over coastal the 2–4 km layer is mixed below 1 km within 2 d over the cities in southern West Africa (SWA), thereby exacerbat- Gulf of Guinea and that the magnitude of the cloud venting is ing air pollution problems. -

Towards a National Ocean Policy in Sao Tome And

TOWARDS A NATIONAL OCEAN POLICY IN SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE Mé-Chinhô Costa Alegre The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2009 - 2010 DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK, 2009 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Sao Tome and Principe, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of West Indies. © 2009 Me-Chinho Costa Alegre. All rights reserved. - i - Abstract The Oceans role to Earth’s environment is broadly recognized and thus there is a growing awareness on environment issues in order to secure preservation of marine resources, food security, sustainability of life at sea and cope with the effects of climate change. Considering that Sao Tome and Principe is a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), a attention will be given to the strategies, policies, legal and institutional approaches among the SIDS around the world and particularly in the Caribbean Region, paying special attention to Barbados experience. The report will consider too the strong pressure on coastal land for construction, tourism developments and other economic activities. The report addresses these issues with reference to the predictable constraint of limited human and financial resources typical of SIDS. In addition, international cooperation among SIDS will be examined in order to understand the Regional integrated policies and strategies needed to tackle common concerns and improve efficiency in the application of resources to implement international instruments. The concept of a Large Marine Ecosystem approach is considered in this analysis of regional cooperation. -

Equatorial Guinea Constitution

Constitution of The Republic of Equatorial Guinea, 1991 Amended to January 17, 1995 Table of Contents PREAMBLE PART ONE Fundamental Principles of the State PART TWO Chapter I Powers and Organs of the State Chapter II The President of the Republic Chapter III The Council of Ministers Chapter IV The Prime Minister Chapter V The National Assembly Chapter VI Judicial Power Chapter VII The Constitutional Council Chapter VIII The Higher Judicial Council PART THREE The Armed Forces, State Security and National Defense PART FOUR Local Communities PART FIVE Revision of the Constitution SPECIAL PROVISIONS FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the people of Equatorial Guinea, conscious of our responsibility before God and history; Driven by the will to safeguard our independence, organize and consolidate our national unity; Desirous of upholding the authoritic African spirit of family and community set-up adapted to the new social and legal structures of the modern world; Conscious of the fact that the charismatic authority of the traditional family is the foundation of the Equato-Guinean Society; Firmly support the principles of social justice and solemnly reaffirm our attachment to the mental freedoms enshrined in the universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948; By virtue of these principles and the free determination of the people; Adopt the following Constitution of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea. PART ONE Fundamental Principles of the State Article 1: Equatorial Guinea shall be a sovereign, independent, republican, unitary, social and democratic state, its supreme values shall be unity, peace, justice, freedom and equality. Multipartism shall be recognized. Its official appellation shall be: THE REPUBLIC OF EQUATORIAL GUINEA.