Darkness and Depth in Early Renaissance Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 3 Issue 2 Artistic Impression

Vol. 3, Issue 2 February, 2021 Burlington Artists League A Word from the President Dear BAL members, Welcome to the February edition of our newsletter. Our previous editor has resigned and until we can find another one, Angela Bostek is serving as our interim editor, taking on yet another responsibility. Our profound thanks, Angela. The month of February conjures up associations with the bleak mid-winter season. On the other hand, it anticipates the arrival of spring, especially if the ground-hog’s prognostications are correct. For us, it means the Small Art Contest. I am pleased that the contest this year has been a success. The entries were as fine as ever and my thanks to all participants and congratulations to the winners! Unfortunately, due to Covid restrictions, we could not have our usual reception to honor the winners. However, as usual, all entries will be on display for the month of February. Please take an hour or so during the month to drop by the gallery to admire all the art submitted for the contest. It’s quite impressive. Now we look forward to the next competition in April. Further information will be forthcoming, watch your email. We hope you will join us for our monthly business meeting by way of Zoom on Thursday, February 18, at 3 p.m. One of the main agenda items will be a discussion of possibly adding a competition at the end of the summer and your input is valuable. In the meantime, stay warm and safe. Jane ********* FEBRUARY CALENDAR OF EVENTS 1st – 28th 14th 18th Jan 22 – Feb 18 Feb. -

Painting Perspective & Emotion Harmonizing Classical Humanism W

Quattrocento: Painting Perspective & emotion Harmonizing classical humanism w/ Christian Church Linear perspective – single point perspective Develops in Florence ~1420s Study of perspective Brunelleschi & Alberti Rules of Perspective (published 1435) Rule 1: There is no distortion of straight lines Rule 2: There is no distortion of objects parallel to the picture plane Rule 3: Orthogonal lines converge in a single vanishing point depending on the position of the viewer’s eye Rule 4: Size diminishes relative to distance. Size reflected importance in medieval times In Renaissance all figures must obey the rules Perspective = rationalization of vision Beauty in mathematics Chiaroscuro – use of strong external light source to create volume Transition over 15 th century Start: Expensive materials (oooh & aaah factor) Gold & Ultramarine Lapis Lazuli powder End: Skill & Reputation Names matter Skill at perspective Madonna and Child (1426), Masaccio Artist intentionally created problems to solve – demonstrating skill ☺ Agonistic Masaccio Dramatic shift in painting in form & content Emotion, external lighting (chiaroscuro) Mathematically constructed space Holy Trinity (ca. 1428) Santa Maria Novella, Florence Patron: Lorenzo Lenzi Single point perspective – vanishing point Figures within and outside the structure Status shown by arrangement Trinity literally and symbolically Vertical arrangement for equality Tribute Money (ca. 1427) Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence Vanishing point at Christ’s head Three points in story Unusual -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs. -

Masaccio's Holy Trinity

Masaccio's Holy Trinity Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, Fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi's discovery in his art. He did this in his fresco called The Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. Have a close look at the painting and at this perspective diagram. Can you see the orthogonals (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance)? Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint -- as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals the vanishing point would be below the base of the cross. My favorite part of this fresco is God's feet. Actually, you can only really see one of them. Why, you may ask, do I have a thing for God's feet (or foot)? Well, think about it for a minute. God is standing in this painting. Doesn't that strike you as odd just a little bit? This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of him in our minds eye -- as an old man with a beard, is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract like that, but as a man. A man who stands -- his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and walks, and, I suppose, even has toenails! In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, just a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives, but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man! This is a good indication of Humanism in the Renaissance. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Egg Tempera Technique

EGG TEMPERA MISCONCEPTIONS By Koo Schadler "Egg tempera is a simple, cheap, easy-to-use technique that produced gorgeous effects...Yet nobody seems to know it." Robert Vickrey (1926-2011) There are many misconceptions regarding egg tempera, and reasons for their existence and persistence. A superficial understanding of tempera limits its potential. This handout hopes to dispel some of the myths. THE REASONS FOR MISCONCEPTIONS Reason #1: The Influence of the Renaissance Egg tempera reached its peak of popularity and achievement in the early Renaissance (approximately 1400- 1450) in Italy, and is notably associated with that time and place. Most Italian, early Renaissance paintings present a less naturalistic, more idealized rendering of the world: minimal light and shadow effects; more high-key (light) values; purer, less dirtied color; cooler color temperatures; less fully three-dimensional forms. For the most part these visual choices are not inevitable to egg tempera. Instead they reflect the less realistic, more spiritually oriented medieval perspective still present in early 1400s Italy (consequently changed by the Renaissance). Because most of these paintings were done in egg tempera, people presume the medium (rather than the culture and its thinking) accounts for this aesthetic. Misconceptions also arise from egg tempera’s association with Italian Renaissance working methods. Masters and guilds taught a successful but prescribed way of developing a painting. Its not the only way to work in tempera, but often is presented as such. Reason #2: Egg Tempera’s Disappearance Renaissance artists aspired to increasing realism in images. Oil painting has advantages (described in Misconception #7) over tempera in depicting the material world and, by the late 1400s, oil became the predominate medium of the Renaissance. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

Lesson Plan: Oil Painting Techniques Grades: MS & HS Art

Lesson Plan: Oil Painting Techniques Grades: MS & HS Art Supplies: • Jars for mediums & solvents (glass jar • Oil Paints or tin can) • Oil Brushes • Paint Medium Comparison Handout • Canvas Panels or Framed (for project) • Basic Oil Painting Techniques • Canvas Paper for worksheet Worksheet • Gesso • Advance Oil Painting Techniques • Odorless Turpenoid Worksheet • Linseed oil • Labels for jars • Palette Knife Lesson One: Introduction to Oil Paints Lesson Two: Exploring Different Methods of Applying Paint (Part One) Lesson Three: Exploring Different Methods of Applying Paint (Part Two) Objectives: • Students will understand the difference between water based & oil based mediums. • Identify & experience oil painting supplies. • Learn & experience various oil painting techniques. • Students will learn about the medium of oil paints, care of supplies, & how to paint with them. • Students will learn how to set up their painting area. Explore different methods of applying paint. • They will learn various techniques & procedures for getting started, painting with oil paints, and cleaning up procedures. Preparation: • Pre-mix the “medium” (1:1 ratio of Linseed Oil & Odorless Turpenoid) & pour in small glass jars (baby food or small canning jars work great). • Copy “Paint Medium Comparison Handout ” one per student (Optional) or display with document projector. • Copy “Basic Oil Painting Techniques Worksheet” onto cardstock or “paper canvas” one per student • Copy “Advance Oil Painting Techniques Worksheet” onto cardstock or “paper canvas” one per student © Michelle C. East - Create Art with ME 2017 Lesson One: Introduction to Oil Paints Delivery: Class One (45 minutes) 1. Oil Paint: a. Observe and experience the differences between water-based and oil-based paints. (See “Paint Medium Comparison” Handout ) i. -

Oil Painting in Educational Settings

Oil Painting in Educational Settings A Guide to Studio Safety Best Practices Recommendations Technical Information SUMMARY For 600 years, oil painting has been the preeminent painting media. Oil painting has documented our cultural heritage and has endured and evolved through the advent of photography, the modernism of the 20th century and into the digital age. Why does oil painting remain relevant? Because no other media carries the same raw power of communication. No other media gives artists the same intensity of color and breadth of mark-making possibilities. There is nothing more natural and enduring than oil painting. Oil painting practice and instruction continues to grow in universities across the country. And standards have evolved over recent decades. Turpentine was once used in virtually all painting studios. Today it is a thing of the past. Leading schools and instructors have incorporated higher standards, which we share, for a safe studio environment and the responsible management of waste. At Gamblin these ideas are not just important to us, they are the founding ideas for our color house. The objective of this guide is to provide two things for you: the proven solutions Gamblin has contributed on the materials side of the equation, and the systems developed by leading schools like the Rhode Island School of Design. Our mission is to lead oil painting and printmaking into the future. This guide is intended to help Instructors, Heads of Departments, and Facilities Managers in schools to have painting studios that are as safe as possible for students and the environment. Gamblin Artists Colors 323 SE Division Pl Portland, Oregon 97202 USA +1 503-235-1945 [email protected] gamblincolors.com CONTENTS Where does the oil in oil painting come from? How does it compare with other mediums? 1 The Nature of Oil Painting Acrylic Colors Water-Miscible Oils How do I choose and manage solvents in our oil painting studio? 2 Definition of an Artist’s Solvent Gamblin Gamsol vs. -

Masaccio (1401-1428) St Peter Distributing Alms to the Poor (Ca 1425)

COVER ART Masaccio (1401-1428) St Peter Distributing Alms to the Poor (ca 1425) OR ALMOST 6 centuries, visitors to the Bran- banking and textiles had made some families wealthy, cacci Chapel in Florence, Italy, have been but many others were left behind. Hundreds of children charmed by the toddler shown here cling- were abandoned each year by poor parents who could ing to his mother, his little rounded rump not afford to raise them. Aid for these foundlings came dangling over her arm. from private charity and from the silk industry, whose FThe frescoes that cover the chapel walls show scenes guild had agreed in 1294 to become the official protec- from the life of St Peter, one of Christ’s 12 disciples. In tor of the city’s abandoned children. While Masaccio was this panel, Peter has traveled to a town in Palestine to working on the Brancacci Chapel, across town the Os- spread the gospel and to do good works following Christ’s pedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital) was being resurrection. A community of believers have sold their built by the silk guild. (The “bambino” insignia of the personal property and pooled their funds, to be distrib- American Academy of Pediatrics was later drawn from a uted according to need. Peter is shown putting money roundel on the hospital’s facade.1) into the hand of the child’s indigent mother. At their feet What motivated this voluntary transfer of wealth to lies a man named Ananias, who secretly withheld part aid poor children? Genuine altruism certainly played a of the proceeds from selling his property and who fell role: rich men had children of their own, and the Re- dead when his deception was exposed. -

L'arte Del Primo Rinascimento

1401 Concorso per la Seconda Porta del Battistero a Firenze. Inizio del Rinascimento 1434 A Firenze è fondata la L’ARTE Signoria dei Medici 1418-36 Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore di 1425-52 Brunelleschi Porta del Paradiso di Ghiberti 1438-40 DEL PRIMO Battaglia di San Romano di Paolo Uccello 1427 Trinità di Masaccio in RINASCIMENTO Santa Maria Novella dal 1400 al 1500 I TEMPI E I LUOGHI Tra il XIV e il XV secolo, i Comuni medievali si trasformarono in Signorie, forme di governo capaci di rispondere all’esigenza di governi più stabili e più forti. In Italia prevalsero cinque Stati i capolavori di grande importanza: Firenze (che formalmente mantenne architettura gli ordinamenti repubblicani e comunali), il Ducato di Milano, ● La Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore di Brunelleschi la Repubblica di Venezia (governata da una oligarchia ● La facciata di Santa Maria Novella mercantile), lo Stato della Chiesa (con Roma sede della a Firenze Curia papale) e il regno di Napoli a Sud. arti visive ● Il David di Donatello A Firenze, nel 1434, il potere si concentrò nelle mani della ● La Porta del Paradiso di Ghiberti famiglia Medici. Cosimo dei Medici, detto il Vecchio, ● La Trinità di Masaccio in Santa Maria Novella ricchissimo banchiere e commerciante, divenne, di fatto, il ● La Battaglia di San Romano padrone incontrastato della città. Anche negli altri piccoli di Paolo Uccello Stati italiani, come il Ducato di Savoia, la Repubblica di ● La Flagellazione di Piero della Francesca Genova, il Ducato di Urbino, le Signorie di Mantova, Ferrara, ● Il Cristo morto di Mantegna Modena e Reggio, le sorti si legarono ai nomi di alcune grandi famiglie. -

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING Part One

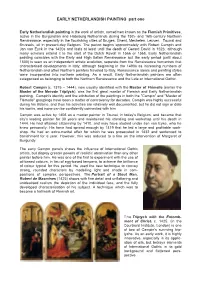

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING part one Early Netherlandish painting is the work of artists, sometimes known as the Flemish Primitives, active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance, especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Leuven, Tounai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium. The period begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the 1420s and lasts at least until the death of Gerard David in 1523, although many scholars extend it to the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1566 or 1568. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but the early period (until about 1500) is seen as an independent artistic evolution, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterised developments in Italy; although beginning in the 1490s as increasing numbers of Netherlandish and other Northern painters traveled to Italy, Renaissance ideals and painting styles were incorporated into northern painting. As a result, Early Netherlandish painters are often categorised as belonging to both the Northern Renaissance and the Late or International Gothic. Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), now usually identified with the Master of Flémalle (earlier the Master of the Merode Triptych), was the first great master of Flemish and Early Netherlandish painting. Campin's identity and the attribution of the paintings in both the "Campin" and "Master of Flémalle" groupings have been a matter of controversy for decades. Campin was highly successful during his lifetime, and thus his activities are relatively well documented, but he did not sign or date his works, and none can be confidently connected with him.