Distribution of Convective Lower Halocline Water in the Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico) by Stephen Alexander Daire A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the USC Graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Technology) May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Stephen Daire “History is just a 25,000-year dash from the trees to the starship; and while it’s going on its wild and woolly but it’s only like that, and then you’re in the starship.” – Terence McKenna. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... xii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... xiii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ xvi Chapter 1 Planetary Sciences, Cave Survey, & Human Evolution................................................. 1 1.1. Topic & Area of Interest: Exploration & Survey ....................................................................12 -

D5.3 Interaction Between Currents, Wave, Structure and Subsoil

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 05, 2021 D5.3 Interaction between currents, wave, structure and subsoil Christensen, Erik Damgaard; Sumer, B. Mutlu; Schouten, Jan-Joost; Kirca, Özgür; Petersen, Ole; Jensen, Bjarne; Carstensen, Stefan; Baykal, Cüneyt; Tralli, Aldo; Chen, Hao Total number of authors: 19 Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Christensen, E. D., Sumer, B. M., Schouten, J-J., Kirca, Ö., Petersen, O., Jensen, B., Carstensen, S., Baykal, C., Tralli, A., Chen, H., Tomaselli, P. D., Petersen, T. U., Fredsøe, J., Raaijmakers, T. C., Kortenhaus, A., Hjelmager Jensen, J., Saremi, S., Bolding, K., & Burchard, H. (2015). D5.3 Interaction between currents, wave, structure and subsoil. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your -

The Effects of Haloclines on the Vertical Distribution and Migration of Zooplankton

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 278 (2002) 111–134 www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe The effects of haloclines on the vertical distribution and migration of zooplankton Laurence A. Lougee *, Stephen M. Bollens1, Sean R. Avent 2 Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies and the Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 3150 Paradise Drive, Tiburon, CA 94920, USA Received 28 April 2000; received in revised form 29 May 2002; accepted 18 July 2002 Abstract While the influence of horizontal salinity gradients on the distribution and abundance of planktonic organisms in estuaries is relatively well known, the effects of vertical salinity gradients (haloclines) are less well understood. Because biological, chemical, and physical conditions can vary between different salinity strata, an understanding of the behavioral response of zooplankton to haloclines is crucial to understanding the population biology and ecology of these organisms. We studied four San Francisco Bay copepods, Acartia (Acartiura) spp., Acartia (Acanthacartia) spp., Oithona davisae, and Tortanus dextrilobatus, and one species of larval fish (Clupea pallasi), in an attempt to understand how and why zooplankton respond to haloclines. Controlled laboratory experiments involved placing several individuals of each species in two 2-m-high tanks, one containing a halocline (magnitude varied between 1.4 and 10.0 psu) and the other without a halocline, and recording the location of each organism once every hour for 2–4 days using an automated video microscopy system. Results indicated that most zooplankton changed their vertical distribution and/or migration in response to haloclines. For the smaller taxa (Acartiura spp., Acanthacartia spp., and O. -

Downloaded 10/03/21 08:00 PM UTC

MAY 2005 P I N K E L 645 Near-Inertial Wave Propagation in the Western Arctic ROBERT PINKEL Marine Physical Laboratory, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California (Manuscript received 11 April 2003, in final form 8 October 2004) ABSTRACT From October 1997 through October 1998, the Surface Heat Budget of the Arctic (SHEBA) ice camp drifted across the western Arctic Ocean, from the central Canada Basin over the Northwind Ridge and across the Chukchi Cap. During much of this period, the velocity and shear fields in the upper ocean were monitored by Doppler sonar. Near-inertial internal waves are found to be the dominant contributors to the superinertial motion field. Typical rms velocities are 1–2 cm sϪ1. In this work, the velocity and shear variances associated with upward- and downward-propagating wave groups are quantified. Patterns are detected in these variances that correlate with underlying seafloor depth. These are explored with the objective of assessing the role that these extremely low-energy near-inertial waves play in the larger-scale evolution of the Canada Basin. The specific focus is the energy flux delivered to the slopes and shelves of the basin, available for driving mixing at the ocean boundaries. The energy and shear variances associated with downward-propagating waves are relatively uniform over the entire SHEBA drift, independent of the season and depth of the underlying topography. Variances associated with upward-propagating waves follow a (depth)Ϫ1/2 dependence. Over the deep slopes, vertical wavenumber spectra of upward-propagating waves are blue-shifted relative to their downward counterparts, perhaps a result of reflection from a sloping seafloor. -

Fishes Associated with Oil and Gas Platforms in Louisiana's River-Influenced Nearshore Waters

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2016 Fishes Associated with Oil and Gas Platforms in Louisiana's River-Influenced Nearshore Waters Ryan Thomas Munnelly Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Munnelly, Ryan Thomas, "Fishes Associated with Oil and Gas Platforms in Louisiana's River-Influenced Nearshore Waters" (2016). LSU Master's Theses. 1070. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1070 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FISHES ASSOCIATED WITH OIL AND GAS PLATFORMS IN LOUISIANA’S RIVER- INFLUENCED NEARSHORE WATERS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences by Ryan Thomas Munnelly B.S., University of North Carolina Wilmington, 2011 May 2016 The Blind Men and the Elephant It was six men of Indostan To learning much inclined, Who went to see the Elephant The Fourth reached out an eager hand, (Though all of them -

Internal Waves in the Ocean: a Review

REVIEWSOF GEOPHYSICSAND SPACEPHYSICS, VOL. 21, NO. 5, PAGES1206-1216, JUNE 1983 U.S. NATIONAL REPORTTO INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEODESYAND GEOPHYSICS 1979-1982 INTERNAL WAVES IN THE OCEAN: A REVIEW Murray D. Levine School of Oceanography, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 Introduction dispersion relation. A major advance in describing the internal wave field has been the This review documents the advances in our empirical model of Garrett and Munk (Garrett and knowledge of the oceanic internal wave field Munk, 1972, 1975; hereafter referred to as GM). during the past quadrennium. Emphasis is placed The GM model organizes many diverse observations on studies that deal most directly with the from the deep ocean into a fairly consistent measurement and modeling of internal waves as statistical representation by assuming that the they exist in the ocean. Progress has come by internal wave field is composed of a sum of realizing that specific physical processes might weakly interacting waves of random phase. behave differently when embedded in the complex, Once a kinematic description of the wave field omnipresent sea of internal waves. To understand is determined, it may be possible to assess . fully the dynamics of the internal wave field quantitatively the dynamical processes requires knowledge of the simultaneous responsible for maintaining the observed internal interactions of the internal waves with other waves. The concept of a weakly interacting oceanic phenomena as well as with themselves. system has been exploited in formulating the This report is not meant to be a comprehensive energy balance of the internal wave field (e.g., overview of internal waves. -

Papua New Guinea: Tufi, New Ireland & Milne Bay | X-Ray Mag Issue #50

Tufi, New Ireland & Milne Bay PapuaText and photos by Chritopher New Bartlett Guinea 35 X-RAY MAG : 50 : 2012 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO travel PNG Is there another country Located just south of the Equator anywhere with so much and to the north of Australia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a diversity? The six million diver’s paradise with the fourth inhabitants of this nation of largest surface area of coral reef mountains and islands are ecosystem in the world (40,000km2 spread over 463,000km2 of of reefs, seagrass beds and man- groves in 250,000km2 of seas), and mountainous tropical for- underwater diversity with 2,500 ests and speak over 800 species of fish, corals and mol- different languages (12 luscs. There are more dive sites percent of the world total). than you can shake a stick at with many more to be discovered and Papua New Guinea occu- barely a diver on them. The dive pies half of the third largest centres are so far apart that there island in the world as well is only ever one boat at any dive site. as 160 other islands and It is one of the few places left in Moorish idoll (above); There are colorful cor- 500 named cays. the world where a diver can see als everywhere (left); Schools of fish under the dive boat in the harbor (top). PREVIOUS PAGE: Clown anemonefish on sea anemone 36 X-RAY MAG : 50 : 2012 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: Diver and whip corals on reef; Beach view at Tufi; View of the fjords of travel PNG from the air PNG the misty clouds at the swath of trees below, occasionally cut by the hairline crack of a path or the meandering swirls of a river. -

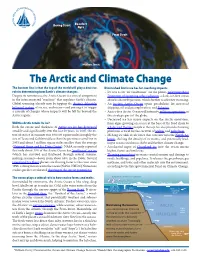

The Arctic and Climate Change the Bottom Line Is That the Top of the World Will Play a Decisive Diminished Arctic Ice Has Far-Reaching Impacts

Bering Strait Beaufort Gyre Fram Strait Hudson Strait The Arctic and Climate Change The bottom line is that the top of the world will play a decisive Diminished Arctic ice has far-reaching impacts. role in determining how Earth’s climate changes. • Ice acts as an “air conditioner” for the planet, reflecting about Despite its remoteness, the Arctic Ocean is a critical component 70 percent of incoming solar radiation; a dark, ice-free ocean in the interconnected “machine” that regulates Earth’s climate. absorbs about 90 percent, which further accelerates warming. Global warming already may be tipping the Arctic’s delicately • An ice-free Arctic Ocean opens possibilities for increased balanced system of air, ice, and ocean—and poising it to trigger shipping, oil and gas exploration, and fisheries. a cascade of changes whose impacts will be felt far beyond the • An ice-free Arctic Ocean will intensify military operations in Arctic region. this strategic part of the globe. • Decreased ice has major impacts on the Arctic ecosystem, Will the Arctic retain its ice? from algae growing on sea ice at the base of the food chain to Both the extent and thickness of Arctic sea ice has decreased whales and Iñupiaq people at the top. Ice also provides hunting steadily and significantly over the last 50 years. In 2007, the ex- platforms critical for the survival of walrus and polar bear. tent of sea ice in summer was 490,000 square miles (roughly the • Melting ice adds fresh water that can flow into the North At- size of Texas and California) less than the previous record low in lantic, shifting the density of its waters, and potentially lead- 2005 and about 1 million square miles smaller than the average ing to ocean circulation shifts and further climate change. -

Lecture Notes in Oceanography

Lecture Notes in Oceanography by Matthias Tomczak Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia School of Chemistry, Physics & Earth Sciences http://www.es.flinders.edu.au/~mattom/IntroOc/index.html 1996-2000 Contents Introduction: an opening lecture General aims and objectives Specific syllabus objectives Convection Eddies Waves Qualitative description and quantitative science The concept of cycles and budgets The Water Cycle The Water Budget The Water Flux Budget The Salt Cycle Elements of the Salt Flux Budget The Nutrient Cycle The Carbon Cycle Lecture 1. The place of physical oceanography in science; tools and prerequisites: projections, ocean topography The place of physical oceanography in science The study object of physical oceanography Tools and prerequisites for physical oceanography Projections Topographic features of the oceans Scales of graphs Lecture 2. Objects of study in Physical Oceanography The geographical and atmospheric framework Lecture 3. Properties of seawater The Concept of Salinity Electrical Conductivity Density Lecture 4. The Global Oceanic Heat Budget Heat Budget Inputs Solar radiation Heat Budget Outputs Back Radiation Direct (Sensible) Heat Transfer Between Ocean and Atmosphere Evaporative Heat Transfer The Oceanic Mass Budget Lecture 5. Distribution of temperature and salinity with depth; the density stratification Acoustic Properties Sound propagation Nutrients, oxygen and growth-limiting trace metals in the ocean Lecture 6. Aspects of Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Classification of forces for oceanography Newton's Second Law in oceanography ("Equation of Motion") Inertial motion Geostrophic flow The Ekman Layer Lecture Notes in Oceanography by Matthias Tomczak 2 Upwelling Lecture 7. Thermohaline processes; water mass formation; the seasonal thermocline Circulation in Mediterranean Seas Lecture 8. The ocean and climate El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Lecture 9. -

Hydrodynamic Capacity Study of the Wave-Energized Baltic Aeration Pump

Hydrodynamic Capacity Study of the Wave-Energized Baltic Aeration Pump General Applicability to the Baltic Sea and Location Study for a Pilot Project in Kanholmsfjarden¨ Christoffer Carstens March 2008 TRITA-LWR Master Thesis ISSN 1651-064X LWR-EX-08-05 c Christoffer Carstens 2008 Master of Science thesis KTH-Water Resources Engineering Department of Land and Water Resources Engineering Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM, Sweden ii Abstract To counteract one of the most urgent environmental issues in the Baltic Sea; eutrophication, excessive algal blooms and hypoxia, a proposal to use wave energy to pump oxygen-rich surface water towards the sea bottom is investigated. Proposals have suggested that 100 kg of oxygen per second is needed to oxygenate bottom water and enhance binding of phosphorus to bottom sediments. This corresponds to 10 000 m3/s of oxygen-rich surface water. This thesis investigates a wave-powered device to facilitate this oxygen flux. Results give expected water flow rates between 0.15{0.40 m3/s and meter breakwater. The mean specific wave power for the analyzed wave data is calculated to be between 3{4 kW/m wave crest and the median to 1 kW/m. This study indicate, however, that the energy fluxes in the Baltic Proper are significantly higher. The study gives that the wave climate of the Baltic Sea is sufficiently intense to facilitate vertical pumping with a feasible number of breakwaters. A full-scale implementation in the Baltic Sea would require some 300 to 1 200 floating breakwaters of a length of 50 m each. -

Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida

Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program report for the State of Florida Item Type monograph Publisher Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Download date 09/10/2021 18:01:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/41152 ISSN 1930-1448 Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida KARA R. RADABAUGH, STEPHEN P. GEIGER, RYAN P. MOYER, EDITORS Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Technical Report No. 22 • 2019 MyFWC.com Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida KARA R. RADABAUGH, STEPHEN P. GEIGER, RYAN P. MOYER, EDITORS Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute 100 Eighth Avenue Southeast St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 MyFWC.com Technical Report 22 • 2019 Ron DeSantis Governor of Florida Eric Sutton Executive Director Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission The Fish and Wildlife Research Institute is a division of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which “[manages] fish and wildlife resources for their long-term well-being and the benefit of people.” The Institute conducts applied research pertinent to managing fishery resources and species of special concern in Florida. Pro- grams focus on obtaining the data and information that managers of fish, wildlife, and ecosystems need to sustain Florida’s natural resources. Topics include managing recreationally and commercially important fish and wildlife species; preserving, managing, and restoring terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats; collecting information related to population status, habitat requirements, life history, and recovery needs of upland and aquatic species; synthesizing ecological, habitat, and socioeconomic information; and developing educational and outreach programs for classroom educators, civic organizations, and the public. -

Density and Stratification Density of Water Ocean Surface Temperature

Density of water density = mass/volume units: g/cm 3 (= g/ml = kg/L) Effect of Temperature on Density density of water - @ 4 oC and 1 atm pressure fresh:1.000 g/cm 3 (by definition!) Density and Stratification sea: 1.027 g/cm 3 (on average) what determines water density? temperature – inverse relationship the major players of the ocean’s layers lower temp = higher density higher temp = lower density salinity – direct relationship lower sal = lower density higher sal = higher density pressure water is essentially (but not exactly) incompressible but at very high pressures (deep depths) – pressure increases density sea level would be ~30-50 m higher without pressure effect Ocean surface temperature often called sea surface temperature or SST strongly correlates with latitude because insolation (amount of sunlight striking Earth’s surface) is high at low latitudes & low at high latitudes surface ocean isotherms (lines of equal temperature) generally trend east-west except where deflected toward poles or equator by currents warm water carried poleward on western side of ocean basins Gulf Stream, Kuroshio Current – Northern Hemisphere Brazil Current, East Australia Current – Southern Hemisphere cooler water carried equatorward on eastern side of ocean basins Canary Current, California Current – Northern Hemisphere Benguela Current, Peru Current – Southern Hemisphere SST overall pattern highest in the tropics (~25-29 oC) where insolation is highest decreases poleward with decreasing insolation negative temperatures