Fishery Resource Use of an Offshore Dredged Material Mound by Kevin J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Introduction to the Shantou Intertidal Wetland, Southern China

AA BriefBrief IntroductionIntroduction toto thethe ShantouShantou IntertidalIntertidal Wetland,Wetland, SouthernSouthern ChinaChina Y.Y. W.W. ZhouaZhoua*.*. G.G. Z.Z. ChenChen SchoolSchool ofof EnvironmentalEnvironmental ScienceScience andand Engineering,Engineering, SunSun YatYat--sensen University,University, Guangzhou,Guangzhou, ChinaChina PR;PR; ** EE--mail:mail: [email protected]@163.com 11 IntroductionIntroduction • Shantou City is one of the most developed cities in southeast coastal area of China. • It had a high population of 4,846,400 . The population density was 2,348 per km2, GDP was 1,700 US $,in 2003. • The current use of the Shantou Intertidal Wetland includes: • briny and limnetic aquaculture, • reclamation for farmland and municipal estate, • transition to the salt field or tourism park, • natural wetland as the habitat of resident and migratory wildlife. 2.2. CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof ShantouShantou IntertidalIntertidal WetlandWetland 2.1 Environmental characteristics The total area of the Shantou Intertidal Wetland is 1,435.29 ha . The demonstration site’s area is 3,475.2 ha , including 4 parts: Fig. 1 Demonstrated content of sub demonstration sites No Demon site Demonstrated Content Area/ha 1 Hexi biodiversity of water weed 512.4 2 Sanyuwei aquiculture and the biological treatment of waste water 1639.5 3 Suaiwang secondary mangrove for birds habitat 388.7 4 Waisha Eco-tourism 934.6 2.22.2 ClimateClimate • The climate is warm all year round with high temperatures and abundant light, and clearly differentiated dry and wet seasons. • Mean annual duration of sunshine: 954.2 hrs. • Historical average air temperature : 23.1 °C. • Average high temperature :38.8 °C • Average low temperature : 15.8 °C. -

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico) by Stephen Alexander Daire A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the USC Graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Technology) May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Stephen Daire “History is just a 25,000-year dash from the trees to the starship; and while it’s going on its wild and woolly but it’s only like that, and then you’re in the starship.” – Terence McKenna. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... xii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... xiii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ xvi Chapter 1 Planetary Sciences, Cave Survey, & Human Evolution................................................. 1 1.1. Topic & Area of Interest: Exploration & Survey ....................................................................12 -

D5.3 Interaction Between Currents, Wave, Structure and Subsoil

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 05, 2021 D5.3 Interaction between currents, wave, structure and subsoil Christensen, Erik Damgaard; Sumer, B. Mutlu; Schouten, Jan-Joost; Kirca, Özgür; Petersen, Ole; Jensen, Bjarne; Carstensen, Stefan; Baykal, Cüneyt; Tralli, Aldo; Chen, Hao Total number of authors: 19 Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Christensen, E. D., Sumer, B. M., Schouten, J-J., Kirca, Ö., Petersen, O., Jensen, B., Carstensen, S., Baykal, C., Tralli, A., Chen, H., Tomaselli, P. D., Petersen, T. U., Fredsøe, J., Raaijmakers, T. C., Kortenhaus, A., Hjelmager Jensen, J., Saremi, S., Bolding, K., & Burchard, H. (2015). D5.3 Interaction between currents, wave, structure and subsoil. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your -

Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20Th Century

u.s. Fish and Wildlife Service Co l\Ietland Trends In the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century November 2004 A National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century Ralph W. Tiner1, Irene J. Huber2, Todd Nuerminger2, and Aimée L. Mandeville3 1U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wetlands Inventory Program Northeast Region 300 Westgate Center Drive Hadley, MA 01035 2Natural Resources Assessment Group Department of Plant and Soil Sciences University of Massachusetts Stockbridge Hall Amherst, MA 01003 3Department of Natural Resources Science Environmental Data Center University of Rhode Island 1 Greenhouse Road, Room 105 Kingston, RI 02881 November 2004 National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report between U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, University of Rhode Island, and Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management This report should be cited as: Tiner, R.W., I.J. Huber, T. Nuerminger, and A.L. Mandeville. 2004. Coastal Wetland Trends in the Narragansett Bay Estuary During the 20th Century. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Northeast Region, Hadley, MA. In cooperation with the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and the University of Rhode Island. National Wetlands Inventory Cooperative Interagency Report. 37 pp. plus appendices. Table of Contents Page Introduction 1 Study Area 1 Methods 5 Data Compilation 5 Geospatial Database Construction and GIS Analysis 8 Results 9 Baywide 1996 Status 9 Coastal Wetlands and Waters 9 500-foot Buffer Zone 9 Baywide Trends 1951/2 to 1996 15 Coastal Wetland Trends 15 500-foot Buffer Zone Around Coastal Wetlands 15 Trends for Pilot Study Areas 25 Conclusions 35 Acknowledgments 36 References 37 Appendices A. -

Species Anchoa Analis (Miller, 1945)

FAMILY Engraulidae Gill, 1861 - anchovies [=Engraulinae, Stolephoriformes, Coilianini, Anchoviinae, Setipinninae, Cetengraulidi] GENUS Amazonsprattus Roberts, 1984 - pygmy anchovies Species Amazonsprattus scintilla Roberts, 1984 - Rio Negro pygmy anchovy GENUS Anchoa Jordan & Evermann, 1927 - anchovies [=Anchovietta] Species Anchoa analis (Miller, 1945) - longfin Pacific anchovy Species Anchoa argentivittata (Regan, 1904) - silverstripe anchovy, Regan's anchovy [=arenicola] Species Anchoa belizensis (Thomerson & Greenfield, 1975) - Belize anchovy Species Anchoa cayorum (Fowler, 1906) - Key anchovy Species Anchoa chamensis Hildebrand, 1943 - Chame Point anchovy Species Anchoa choerostoma (Goode, 1874) - Bermuda anchovy Species Anchoa colonensis Hildebrand, 1943 - narrow-striped anchovy Species Anchoa compressa (Girard, 1858) - deepbody anchovy Species Anchoa cubana (Poey, 1868) - Cuban anchovy [=astilbe] Species Anchoa curta (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - short anchovy Species Anchoa delicatissima (Girard, 1854) - slough anchovy Species Anchoa eigenmannia (Meek & Hildebrand, 1923) - Eigenmann's anchovy Species Anchoa exigua (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - slender anchovy [=tropica] Species Anchoa filifera (Fowler, 1915) - longfinger anchovy [=howelli, longipinna] Species Anchoa helleri (Hubbs, 1921) - Heller's anchovy Species Anchoa hepsetus (Linnaeus, 1758) - broad-striped anchovy [=brownii, epsetus, ginsburgi, perthecatus] Species Anchoa ischana (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) - slender anchovy Species Anchoa januaria (Steindachner, 1879) - Rio anchovy -

The Effects of Haloclines on the Vertical Distribution and Migration of Zooplankton

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 278 (2002) 111–134 www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe The effects of haloclines on the vertical distribution and migration of zooplankton Laurence A. Lougee *, Stephen M. Bollens1, Sean R. Avent 2 Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies and the Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 3150 Paradise Drive, Tiburon, CA 94920, USA Received 28 April 2000; received in revised form 29 May 2002; accepted 18 July 2002 Abstract While the influence of horizontal salinity gradients on the distribution and abundance of planktonic organisms in estuaries is relatively well known, the effects of vertical salinity gradients (haloclines) are less well understood. Because biological, chemical, and physical conditions can vary between different salinity strata, an understanding of the behavioral response of zooplankton to haloclines is crucial to understanding the population biology and ecology of these organisms. We studied four San Francisco Bay copepods, Acartia (Acartiura) spp., Acartia (Acanthacartia) spp., Oithona davisae, and Tortanus dextrilobatus, and one species of larval fish (Clupea pallasi), in an attempt to understand how and why zooplankton respond to haloclines. Controlled laboratory experiments involved placing several individuals of each species in two 2-m-high tanks, one containing a halocline (magnitude varied between 1.4 and 10.0 psu) and the other without a halocline, and recording the location of each organism once every hour for 2–4 days using an automated video microscopy system. Results indicated that most zooplankton changed their vertical distribution and/or migration in response to haloclines. For the smaller taxa (Acartiura spp., Acanthacartia spp., and O. -

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species ID Guide

Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Identification Guide Forage Species Identification Guide Basic Morphology Dorsal fin Lateral line Caudal fin This guide provides descriptions and These species are subject to the codes for the forage species that vessels combined 1,700-pound trip limit: Opercle and dealers are required to report under Operculum • Anchovies the Mid-Atlantic Council’s Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment. Find out • Argentines/Smelt Herring more about the amendment at: • Greeneyes Pectoral fin www.mafmc.org/forage. • Halfbeaks Pelvic fin Anal fin Caudal peduncle All federally permitted vessels fishing • Lanternfishes in the Mid-Atlantic Forage Species Dorsal Right (lateral) side Management Unit and dealers are • Round Herring required to report catch and landings of • Scaled Sardine the forage species listed to the right. All species listed in this guide are subject • Atlantic Thread Herring Anterior Posterior to the 1,700-pound trip limit unless • Spanish Sardine stated otherwise. • Pearlsides/Deepsea Hatchetfish • Sand Lances Left (lateral) side Ventral • Silversides • Cusk-eels Using the Guide • Atlantic Saury • Use the images and descriptions to identify species. • Unclassified Mollusks (Unmanaged Squids, Pteropods) • Report catch and sale of these species using the VTR code (red bubble) for • Other Crustaceans/Shellfish logbooks, or the common name (dark (Copepods, Krill, Amphipods) blue bubble) for dealer reports. 2 These species are subject to the combined 1,700-pound trip limit: • Anchovies • Argentines/Smelt Herring • -

Upside-Down'' Estuaries of the Florida Everglades

Limnol. Oceanogr., 51(1, part 2), 2006, 602±616 q 2006, by the American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, Inc. Relating precipitation and water management to nutrient concentrations in the oligotrophic ``upside-down'' estuaries of the Florida Everglades Daniel L. Childers1 Department of Biological Sciences and SERC, Florida International University, Miami, Florida 33199 Joseph N. Boyer Southeast Environmental Research Center, Florida International University, Miami, Florida 33199 Stephen E. Davis Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 Christopher J. Madden and David T. Rudnick Coastal Ecosystems Division, South Florida Water Management District, 3301 Gun Club Road, West Palm Beach, Florida 33416 Fred H. Sklar Everglades Division, South Florida Water Management District, 3301 Gun Club Road, West Palm Beach, Florida 33416 Abstract We present 8 yr of long-term water quality, climatological, and water management data for 17 locations in Everglades National Park, Florida. Total phosphorus (P) concentration data from freshwater sites (typically ,0.25 mmol L21,or8mgL21) indicate the oligotrophic, P-limited nature of this large freshwater±estuarine landscape. Total P concentrations at estuarine sites near the Gulf of Mexico (average ø0.5 m mol L21) demonstrate the marine source for this limiting nutrient. This ``upside down'' phenomenon, with the limiting nutrient supplied by the ocean and not the land, is a de®ning characteristic of the Everglade landscape. We present a conceptual model of how the seasonality of precipitation and the management of canal water inputs control the marine P supply, and we hypothesize that seasonal variability in water residence time controls water quality through internal biogeochemical processing. -

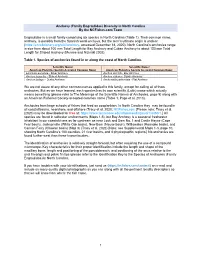

NC-Anchovy-And-Identification-Key

Anchovy (Family Engraulidae) Diversity in North Carolina By the NCFishes.com Team Engraulidae is a small family comprising six species in North Carolina (Table 1). Their common name, anchovy, is possibly from the Spanish word anchova, but the term’s ultimate origin is unclear (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/anchovy, accessed December 18, 2020). North Carolina’s anchovies range in size from about 100 mm Total Length for Bay Anchovy and Cuban Anchovy to about 150 mm Total Length for Striped Anchovy (Munroe and Nizinski 2002). Table 1. Species of anchovies found in or along the coast of North Carolina. Scientific Name/ Scientific Name/ American Fisheries Society Accepted Common Name American Fisheries Society Accepted Common Name Engraulis eurystole - Silver Anchovy Anchoa mitchilli - Bay Anchovy Anchoa hepsetus - Striped Anchovy Anchoa cubana - Cuban Anchovy Anchoa lyolepis - Dusky Anchovy Anchoviella perfasciata - Flat Anchovy We are not aware of any other common names applied to this family, except for calling all of them anchovies. But as we have learned, each species has its own scientific (Latin) name which actually means something (please refer to The Meanings of the Scientific Names of Anchovies, page 9) along with an American Fisheries Society-accepted common name (Table 1; Page et al. 2013). Anchovies from large schools of fishes that feed on zooplankton. In North Carolina they may be found in all coastal basins, nearshore, and offshore (Tracy et al. 2020; NCFishes.com [Please note: Tracy et al. (2020) may be downloaded for free at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/sfcproceedings/vol1/iss60/1.] All species are found in saltwater environments (Maps 1-6), but Bay Anchovy is a seasonal freshwater inhabitant in our coastal rivers as far upstream as near Lock and Dam No. -

Ecosystem Element Conceptual Model Tidal Marsh

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Regional Ecosystem Restoration Implementation Plan Ecosystem Element Conceptual Model Tidal Marsh Prepared by: Ronald T. Kneib, University of Georgia Marine Institute [email protected] and • Charles A. Simenstad, School of Aquatic & Fisheries Sciences, University of Washington • Matt L. Nobriga, CALFED Science Program • Drew M. Talley, San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, San Francisco State University, Romberg Tiburon Center Date of Model: October 2008 Status of Peer Review: Completed peer review on October 2008. Model content and format are suitable and model is ready for use in identifying and evaluating restoration actions. Suggested Citation: Kneib R, Simenstad C, Nobriga M, Talley D. 2008. Tidal marsh conceptual model. Sacramento (CA): Delta Regional Ecosystem Restoration Implementation Plan. For further inquiries on the DRERIP conceptual models, please contact Brad Burkholder at [email protected] or Steve Detwiler at [email protected]. PREFACE This Conceptual Model is part of a suite of conceptual models which collectively articulate the current scientific understanding of important aspects of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta ecosystem. The conceptual models are designed to aid in the identification and evaluation of ecosystem restoration actions in the Delta. These models are designed to structure scientific information such that it can be used to inform sound public policy. The Delta Conceptual Models include both ecosystem element models (including process, habitat, and stressor models) and species life history models. The models were prepared by teams of experts using common guidance documents developed to promote consistency in the format and terminology of the models http://www.delta.dfg.ca.gov/erpdeltaplan/science_process.asp . -

Mangroves and Saltmarshes of Moreton Bay

https://moretonbayfoundation.org/ 1 Moreton Bay Quandamooka & Catchment: Past, present, and future Chapter 5 Habitats, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function Mangroves and saltmarshes of Moreton Bay Abstract The mangroves and saltmarshes of Moreton Bay comprising 18,400 ha are important habitats for biodiversity and providing ecosystem services. Government policy and legislation largely reflects their importance with protection provided through a range of federal and state laws, including the listing of saltmarsh communities in 2013 under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Local communities also conserve and manage mangroves and saltmarshes. Recent scientific research on these ecosystems in Moreton Bay has described food webs, habitat use by fauna, carbon sequestration and effects of climate change. The area of saltmarsh has declined by 64% since 1955 due to mangrove encroachment into saltmarsh habitats and past conversion to rural and urban land uses. Mangrove encroachment into saltmarsh habitats, which has been reported in other locations in Australia and across the world, has increased the area of mangrove habitat by 6.4% over the same period. This is consistent with predictions of habitat changes under climate change, and demonstrates the need for management strategies that ensure these ecosystems are maintained. Keywords: coastal wetlands, intertidal, wetland management, EPBC Act, wetland change, drivers of wetland change, South East Queensland, soil carbon stocks Introduction Mangroves and saltmarshes, which are components of the estuarine wetlands of Moreton Bay, are dominated by salt-tolerant vegetation that occurs from approximately mean sea level to the highest astronomical tidal plane. They occur within the river systems and tidal creeks of Moreton Bay as well as on the comparatively open coasts of the Bay where they fringe both islands and the mainland. -

Full Document (Pdf 2154

White Paper Research Project T1803, Task 35 Overwater Whitepaper OVERWATER STRUCTURES: MARINE ISSUES by Barbara Nightingale Charles A. Simenstad Research Assistant Senior Fisheries Biologist School of Marine Affairs School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) University of Washington, Box 354802 University District Building 1107 NE 45th Street, Suite 535 Seattle, Washington 98105-4631 Washington State Department of Transportation Technical Monitor Patricia Lynch Regulatory and Compliance Program Manager, Environmental Affairs Prepared for Washington State Transportation Commission Department of Transportation and in cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration May 2001 WHITE PAPER Overwater Structures: Marine Issues Submitted to Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Washington Department of Ecology Washington Department of Transportation Prepared by Barbara Nightingale and Charles Simenstad University of Washington Wetland Ecosystem Team School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences May 9, 2001 Note: Some pages in this document have been purposefully skipped or blank pages inserted so that this document will copy correctly when duplexed. TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. WA-RD 508.1 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Overwater Structures: Marine Issues May 2001 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Barbara Nightingale, Charles Simenstad 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) University of Washington, Box 354802 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. University District Building; 1107 NE 45th Street, Suite 535 Agreement T1803, Task 35 Seattle, Washington 98105-4631 12.