Existentialism of DC Comics' Superman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the Represe

Research Space Journal article ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Goodrum, M. Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Goodrum, M. (2018) ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women. Gender & History, 30 (2). ISSN 1468-0424. Link to official URL (if available): https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12361 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Michael Goodrum Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane ran from 1958-1974 and stands as a microcosm of contemporary debates about women and their place in American society. The title itself suggests many of the topics about which women were concerned, or at least were supposed to concern them: the mediation of identity through heterosexual partnership, the pressure to marry and the simultaneous emphasis placed on individual achievement. Concerns about marriage and Lois’ ability to enter into it routinely provide the sole narrative dynamic for stories and Superman engages in different methods of avoiding the matrimonial schemes devised by Lois or her main romantic rival, Lana Lang. -

Supergirl: Volume 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SUPERGIRL: VOLUME 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mahmud A. Asrar,Michael Alan Nelson | 144 pages | 29 Jul 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401247003 | English | United States Supergirl: Volume 4 PDF Book Also, there are some moments where Kara's powers really don't make sense. Supergirl Vol 4 9 "Tempus Fugit" May, Supergirl Vol 4 12 "Cries in the Darkness" August, Matt rated it it was amazing Apr 06, However, I do prefer the more recent issues of the series, which send Kara-El Supergirl's Kryptonian name on a space quest with Krypto the Super-Dog and art by the always dependable Kevin Maguire. The one after that will be straight garbage that no effort whatsoever was put into. Jun 08, Mike marked it as series-in-progress. This issue tells the New 52 origin of Cyborg Superman. Supergirl Vol 4 54 "Statue of Limitations" March, Search books and authors. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. What's worse is how disjointed the story is. Supergirl Vol 4 51 "Making a Splash" December, It was just generic. Harley Quinn Vol. Supergirl Vol 4 47 "Before the Fall" August, Kara is dying of Kryptonite poisoning and has fled Earth. The issue that tracked Zor-El's conflict with Jor-El about how best to save Krypton from destruction was outstanding. Mesmer, one of. Slightly better than the last volume. Science Fiction. Supergirl has Kryptonite poisoning from her run in with H'el, so she takes off into space to 'die alone' Supergirl Vol 4 10 "Hidden Things" June, Enlarge cover. Jan 03, Fraser Sherman rated it it was ok Shelves: graphic-novels. -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016) -

{DOWNLOAD} Earth 2: the Kryptonian Vol 5 Ebook

EARTH 2: THE KRYPTONIAN VOL 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicola Scott,Trevor Scott,Tom Taylor | 176 pages | 08 Dec 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401257576 | English | United States EARTH 2 VOL. 5: THE KRYPTONIAN | DC Time is running out for the Justice League to unlock the Anti-Life cure as they face a deadly new threat on Earth-in addition to the billions of the undead! Their final desperate attempt at finding the cure will take them off-planet for the greatest heist in the history of New Genesis! Reviews Review Policy. Published on. Original pages. Best for. Android 3. Content protection. Read aloud. Learn more. Learn More. Flag as inappropriate. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are. Nice little reference to Bizaro Superman in this, by the way. I was impressed with this entire storyline, and I'm excited to see what happens next. There is a next , right? Someone please tell me there's more! Because I'm obviously too lazy to Google the answer to that Even if you didn't care for this one when it first came out, I'd still say these last few volumes are cool enough to warrant you giving it another shot. Get this review and more at View all 14 comments. Sep 16, Steve rated it liked it Shelves: sequential-art , read-in This one was very flat compared to the previous four volumes, like it lost its purpose and the characters were just going through the motions. Even the twist at the end was just sort of I do have one question, though: On the cover of the book, Val-Zod has Kal-El pinned during a fight, and Power Girl is in the background. -

A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #Depaulheroes

1 A Celebration of Superheroes Virtual Conference 2021 May 01-May 08 #DePaulHeroes Conference organizer: Paul Booth ([email protected]) with Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This has been a strange year, to be sure. My appreciation to everyone who has stuck with us throughout the trials and tribulations of the pandemic. The 2020 Celebration of Superheroes was postponed until 2021, and then went virtual – but throughout it all, over 90% of our speakers, both our keynotes, our featured speakers, and most of our vendors stuck with us. Thank you all so much! This conference couldn’t have happened without help from: • The College of Communication at DePaul University (especially Gina Christodoulou, Michael DeAngelis, Aaron Krupp, Lexa Murphy, and Lea Palmeno) • The University Research Council at DePaul University • The School of Cinematic Arts, The Latin American/Latino Studies Program, and the Center for Latino Research at DePaul University • My research assistants, Elise Fong and Rebecca Woods • Our Keynotes, Dr. Frederick Aldama and Sarah Kuhn (thank you!) • All our speakers… • And all of you! Conference book and swag We are selling our conference book and conference swag again this year! It’s all virtual, so check out our website popcultureconference.com to see how you can order. All proceeds from book sales benefit Global Girl Media, and all proceeds from swag benefit this year’s charity, Vigilant Love. DISCORD and Popcultureconference.com As a virtual conference, A Celebration of Superheroes is using Discord as our conference ‘hub’ and our website PopCultureConference.com as our presentation space. While live keynotes, featured speakers, and special events will take place on Zoom on May 01, Discord is where you will be able to continue the conversation spurred by a given event and our website is where you can find the panels. -

Cross Fire: an Original Companion Novel (Batman Vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice) Free

FREE CROSS FIRE: AN ORIGINAL COMPANION NOVEL (BATMAN VS. SUPERMAN: DAWN OF JUSTICE) PDF Michael Kogge | 144 pages | 16 Feb 2016 | Scholastic Inc. | 9780545916301 | English | United States Cross Fire: An Original Companion Novel of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice – DC Comics Movie It was released on February 16, After saving Metropolis from an alien invasion, Superman is now famous around the world. Meanwhile Gotham City 's own guardian, Batman, would rather fight crime from the shadows. But when the devious Doctor Aesop escapes from Arkham Asylumthe two very different heroes begin investigating the same case and a young boy is caught in the cross fire. The book also includes a full-color insert with images from the feature film. Two weeks after the Battle of Metropolisschoolboy Rory Greeley has been searching for his mother, who has been missing since the Black Zero Event. Instead of informing the authorities of this, he has for the past two weeks been working on a remote controlled drone to search the rubble for her. Superman has been assisting rescue workers by clearing rubble and rescuing trapped civilians since General Zod was defeated. Also a telethon run by the Metropolis News Network is happening that night, to raise money for Cross Fire: An Original Companion Novel (Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice) victims of the attack and help with rebuilding the city. Since the attack, criminals had moved from Metropolis to Gotham out of fear for their lives. Bruce was going to the telethon that night, hoping to raise money for the victims of the event. -

A Identidade Secreta Da Figura: Interpretação Figural, Mímesis E Paradoxo Narrativo Em Quadrinhos De Super-Herói

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS DOUTORADO EM TEORIA DA LITERATURA A Identidade Secreta da Figura: Interpretação Figural, Mímesis e Paradoxo Narrativo em Quadrinhos de Super-Herói Recife, fevereiro de 2015 Cláudio Clécio Vidal Eufrausino A Identidade Secreta da Figura: Interpretação Figural, Mímesis e Paradoxo Narrativo em Quadrinhos de Super-Herói Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Teoria da Literatura Orientador: Prof. Dr. Anco Márcio Tenório Vieira Recife, fevereiro de 2015 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecário Jonas Lucas Vieira, CRB4-1204 E86i Eufrausino, Cláudio Clécio Vidal A identidade secreta da figura: interpretação figural, mímesis e paradoxo narrativo em quadrinhos de super-herói / Cláudio Clécio Vidal Eufrasino. – Recife: O Autor, 2015. 250 f.: il., fig. Orientador: Anco Márcio Tenório Vieira. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Centro de Artes e Comunicação. Letras, 2015. Inclui referências. 1. Literatura. 2. Identidade na literatura. 3. Super-heróis. 4. Histórias em quadrinhos. 5. Mimese. I. Vieira, Anco Márcio Tenório (Orientador). II. Título. 807 CDD (22. ed.) UFPE (CAC 201) CLÁUDIO CLÉCIO VIDAL EUFRAUSINO A IDENTIDADE SECRETA DA FIGURA: Interpretação Figural, Mímesis e Paradoxo Narrativo em Quadrinhos de Super-Herói Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco como requisito para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em TEORIA DA LITERATURA em 20/02/2015. TESE APROVADA PELA BANCA EXAMINADORA: ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Anco Márcio Tenório Vieira Orientador – LETRAS – UFPE ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Ricardo Postal LETRAS – UFPE ____________________________ Prof. -

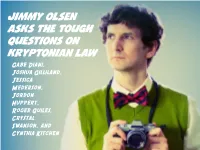

Jimmy Olsen Asks the Tough Questions on Kryptonian

Jimmy Olsen Asks the Tough Questions on Kryptonian Law Gabe Diani, Joshua Gilliland, Jessica Mederson, Jordon Huppert, Roger Quiles, Crystal Swanson, and Cynthia Kitchen Agenda Duty to Rescue Imprisoning Aliens Financial Responsibility for Super Villain Battles? “Phantom Zone” and Cruel & Unusual Punishment? J’onn J’onzz and Identity Theft Does Supergirl Violate U.S. Airspace? Invasion of Privacy And Jeepers More! Jessica Mederson Hero Name: Zippy Sworn Mission: To Help the Underdog Arch Nemesis: Hypocrites Weaknesses: Chocolate, sitcoms, and Celebrity gossip Jordon Huppert Hero Name: Link Skills: Defending the Public, arguing with the man, being a general pain in the Neck Weaknesses: Spiders that aren't Spider- man, usually the facts, being told the odds. Joshua Gilliland Hero Name: Bow Tie Skills: Wielding the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for native file productions Weakness: New Comics on Wednesdays, Chicken tacos Crystal Swanson Hero Name: Pro Hawk V’che Skills: Gather the facts, seek the truth, cross like a boss Weaknesses: 80's hair bands Roger Quiles Hero Name: GameShark Sworn mission: to serve and protect professional video game players Arch nemeses: final bosses everywhere Weaknesses: controllers and keyboards with sticky buttons, cheat codes, and mojitos Cynthia Kitchen Superhero name: Captain Kitty Skills: Defender of contractors; cat whisperer Weaknesses: Sephora; Susiecakes “Jimmy Olsen” Name: James Bartholomew Olsen Occupation: Cub Reporter (75+ years experience) Aliases: Elastic Lad, Giant Turtle Boy, Superlad, Flamebird, -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC.